International Politics and the Spread of Quotas for Women in

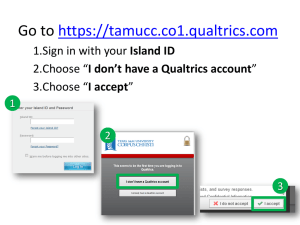

advertisement