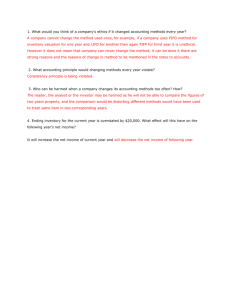

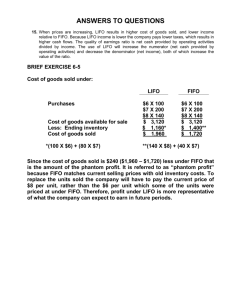

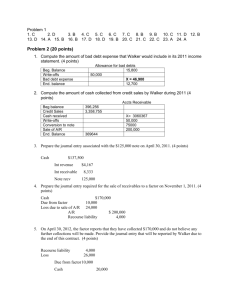

assignment classification table (by topic)

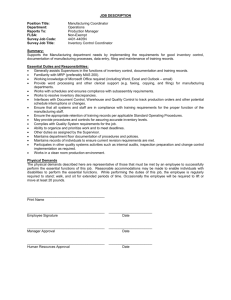

advertisement