Using Monopoly to Teach Intermediate Accounting Students Cynthia

advertisement

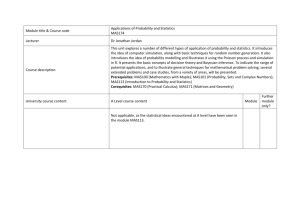

Using Monopoly to Teach Intermediate Accounting Students Cynthia B. Lucking Presbyterian College Abstract Prior studies have shown that non-traditional teaching techniques are an effective method of enhancing student performance and perceptions of learning. This paper reports the observations and outcomes of the use of Monopoly™ as a simulation in an intermediate level accounting course. The objective of this research is to determine if the use of a simulation in an intermediate level accounting course is an effective and engaging method for students to review introductory financial accounting concepts in preparation for intermediate level topics. Introduction Intermediate accounting can be a challenging course to teach due to the one or two semester break most students have between their introductory and intermediate accounting classes. In addition, intermediate level students may have different levels of course preparation as they generally have been taught by several different professors. The use of a common experience, such as playing Monopoly™, to review materials covered in principles of accounting may be an effective way to provide students with a common background to enhance learning and to provide a foundation for intermediate level topics. There is a large body of research investigating the connection between students’ experiences and learning. Dewey (1938), Lewin (1951), and Piaget (1970) all believed that learning takes place when a learner is stimulated by his environment. Based on their work, Kolb (1984), the creator of the Experiential Learning Theory and the Learning Style Inventory, defined learning as “the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience “(p.41). He stated that “Knowledge results from the combination of grasping and transforming experience” (p.41). Halpern and Hakel (2003) also support the use of experiential learning concluding “Lectures work well for learning assessed with recognition tests, but work badly for understanding” (p.40). Both educational and psychological research suggest that the use of an experiential approach to teaching is more effective than presenting material through a lecture format. The use of non-traditional methods such as cases and simulations to help students learn has been supported by many studies including Leong (2005), Saunders and Christopher (2003), and Lewis and Mierzwa (1989). The specific effectiveness of Monopoly™ as a teaching tool to encourage students’ active participation was first studied by Knechel (1989) using MBA students as subjects. He concluded that using the game as a simulation was equally effective as a standard practice set in helping students learn while being more interesting and less time consuming for students to complete. Albrecht (1995), Tanner and Lindquist (1998), Kober and Tarca (2000), and Gamlath (2007) expanded on Knechel’s work and found that the use of a Monopoly ™ simulation enhanced learning, improved social relationships with classmates, and increased students’ enjoyment of the course. These researchers focused primarily on beginning accounting students; this study sought to determine if these effects are also found at the intermediate level. The Simulation Students in an intermediate accounting class were divided into groups of three or four at the end of the third week of the course. Each team was provided with a Monopoly™ game and provided with a rule sheet. The students were given three weeks to complete the assignment. The objectives of the simulation were to: correctly record each economic event in both journal entry and ledger form, properly summarize and communicate the results of the events to external users through the preparation of an income statement, statement of stockholders’ equity, balance sheet, and statement of cash flows, and obtain the largest amount of retained earnings. The game followed traditional Monopoly™ rules beginning with a $1500 investment by shareholders in a real estate development corporation. Play continued for thirty “days” (moves) so monthly financial statements could be prepared. Players were required to purchase a minimum of four properties and construct at least two houses. They were allowed to mortgage properties and to obtain loans in the event of bankruptcy in order to complete a full month of transactions. By passing “Go”, players could earn “property management revenue”. Community Chest and Chance cards were modified to create transactions that related more closely to a business situation. At the end of the month, players were required to record adjusting journal entries for items such as depreciation, interest, and taxes. They also had to reconcile the amount of cash on hand to the balance shown in their accounting records. Finally, they had to prepare the four financial statements. Study Setting Students enrolled in an undergraduate intermediate accounting class (n=15) were assigned the Monopoly™ simulation as a required component of their course. The students were allowed three weeks to complete the simulation. No class time was allocated for the simulation. All of the students in the class were traditional college age. Sixty percent of the students were juniors, 20% were seniors, and 20% were sophomores. The majority of these students intended to major in business with a concentration in accounting (67%), for whom the course was required, and the remaining students came from a variety of majors for whom the course was an elective. The average length of time that had passed since the end of the students’ introductory accounting course was 11.5 months. A survey was administered in-class on the day the simulation was due in order to assess their perceptions of the project. The response scale was 1= Agree Strongly, 2 = Agree, 3 = Neither Agree nor Disagree, 4 = Disagree, and 5 = Strongly Disagree. Results The students agreed that they initially thought the project would be fun when it was assigned (average response 1.7). Their agreement that the project was fun at the end of the simulation was 1.9 so their perceptions had not changed substantially over the course of the assignment. When asked about their agreement with the statement “This project should never be used again!”, the students disagreed (average response 4.3). Their narrative responses showed that they liked the opportunity to work in a group setting for example: “it was fun working with other people in the class” and “playing Monopoly™ with a group was a lot of fun compared to just doing tedious journal entries…”. Students stated that the worst part of the project was the length of time it took to complete and the difficulty in finding time for groups to meet. However, two students commented that there should be more entries required which would require even more time. In general, nonaccounting majors rated the project as less enjoyable even though they felt that they had learned a lot from the project (average response 2.4 versus 2.1 for majors). Students also felt that the simulation provided them with a good way to review material covered in the introductory financial accounting course (average response 1.7). One student stated “The best part of the project was being able to play the game and ask questions as it progressed. By helping each other with the journal entries, we were able to explain what we know and had a better review of the financial accounting concepts.” Summary and Conclusion The objective of this study was to determine if the use of a Monopoly™ simulation in an intermediate level accounting course would provide students with an engaging and effective means of reviewing material covered in their introductory accounting course. The results of this study support previous research which shows that the use of non-traditional teaching aids increase student interest. I found that accounting students enjoyed the simulation and felt that it had helped them to review their previous course work. REFERENCES Albrecht, W.D. (1995). A financial accounting and investment simulation game. Issues in Accounting Education, 10(1), 127-142. Dewey, John. (1938). Experience and Education. New York: Kappa Delta Pi. Gamlath, S. (2007). Outcomes and Observations of an Extended Accounting Board Game. Developments in Business Simulation and Experiential Learning, 34, 132-137. Halpern and Hakel. (2003). Applying the Science of Learning to the University and Beyond: Teaching for Long-Term Retention and Transfer. Change, 35(4), 36-41. Knechel, R.K. (1989). Using a business simulation game as a substitute for a practice set. Issues in Accounting Education, 4(2), 411-424. Kober, R., & Tarca, A. (2000). For Fun or Profit? An Evaluation of an Accounting Simulation Game for University Students. Accounting Research Journal, 15, 98-111. Kolb, David. (1984). Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. Leong, L. (2005). Improving students’ interest in learning: some positive techniques. Journal of Information Systems Education, 16(2), 129-132. Lewin, Kurt. (1951). Field Theory in Social Sciences. New York: Harper & Row. Lewis, D.J. and Mierzwa, I.P. (1989). Gaming: A teaching strategy of adult learners. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 20(2), 80-84. Piaget, Jean. (1970). Genetic Epistemology. New York: Columbia University Press. Saunders, G. and Christopher, J.E. (2003). Teaching outside the box: A look at the use of some nontraditional models in accounting principles courses. The Journal of American Academy of Business, 3(1/2), 162-165. Tanner, M., & Lindquist, T. (1998). Using Monopoly and Team-Games-Tournaments in accounting education: a co-operative learning teaching resource. Accounting Education, 7(2), 139-162.