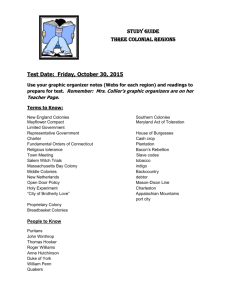

Acts of Trade and Navigation (Navigation Acts) Between 1651 and

advertisement