06. 17th-Century American Society.doc

advertisement

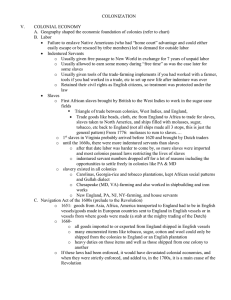

17th-Century American Society Having established most of the thirteen original American colonies, let’s swoop down over them and browse through the images of their daily lives. We’ll need to examine demographics, economics, societal development, and social class structure to uncover the roots of eventual independence and greatness. The elements of greatness were there from the beginning although no one living then could imagine it, least of all the Mother Country, England. We have said that 250,000 people clung to life on the coastal plain by 1700. Those who founded colonies need to be categorized, first. Colonies had been founded by joint-stock companies looking for profits, but also by religious groups that transplanted whole communities with two and three generations intact. Individual businessmen were colonizers as well as private partnerships. That’s the who. Now it remains to discuss issues like: How did they interact? How did each group uniquely face the realities of life in the wilderness? Before we tackle those questions, one idea has to be established from the start. By 1700, there existed in America native-born children of native-born children. The third generation was walking around, and for them, “home” meant America. But they were not “Americans” exactly. In their view they were still Englishmen although we can look back through the colonial experience and posit that they were already a new breed of human. Gathered in coastal villages and along rivers, a culture that was deemed backward by Englishmen in England was brewing. A reordering of social structure was afoot, and its path leads directly to revolution and individual freedom. That is why we can say the American colonists in English colonies in America were “Americans” even though they thought they were Englishmen. America experienced remarkable demographic change. Of those 250,000 people, one half to two thirds arrived as penniless indentured servants. Before we glory in American freedom and culture, let us acknowledge that well over 100,000 of our ancestors were paupers. Most American colonists were farmers. Some were artisans, and a tiny segment was made up of industrial workers. The population was geographically mobile unlike anything in English society. Most indentured servants moved away when freed. Population growth exceeded even the population boom in England. Settlers of New England experienced such rapid growth that the northern population doubled every 27 years, not counting immigration. The healthier climate of New England actually increased the lifespan of New Englanders. In the south, however, life spans of particularly Virginians and Marylanders dropped. Males could expect an average age at death of 48, women 40. Life expectancy did not climb in the south again until 1680 once resistance to disease developed. Then, the southern population boomed four times over in 30 years. From there it doubled every 30 years. This growth was not fueled as one might suspect from higher birth rates. Americans experienced a lower death rate than did Europeans. Males at birth in New England had a life expectancy 12.6 years more than their counterparts in England would enjoy one hundred years later in the 19th century. America’s climate was good for growing people as well as crops. The American population was young. Most indentured servants were from 18-24 years old. They married younger and birthed children younger than in England. While settled societies always have more women (boys die of accidents more), by 1650 America still had a sex ratio in the middle and southern colonies of 6 men to every 1 woman. New England had three men to two women. One thing there was not a lot of in America was single mothers. A look at the demographic of Black Americans concludes the demographic study. Blacks made up 10% of the population by 1700. 1685 was the first year black slaves outnumbered white indentured servants. Ten thousand slaves came between the years of 1698 and 1709 alone. Their lives were short because they did the most dangerous work. By and large no family structure existed. Only the next generation would acquire family life and be diversified into categories like household servants, artisans, and field hands. As Black Americans’ family lives began, a fragile culture reminiscent of Africa began to form. The economy of colonial America was as unstable as its social class structure. Europeans were used to an economic system stabilized by the ancient guild system. Long-established trading houses preserved a consumer base with fixed desires. Nothing like these institutions existed in America. The economy of colonial America ranged from subsistence-level farming on a gradually expanding frontier to attempts at industry. New Englanders tried to launch the industrial revolution first, and failed. They tried iron working and a cloth industry, but the cost of capital (money for investment) and a shortage of workers (who were all in the fields) led to bankruptcy. What did succeed in New England was a multi-stage approach to creating a diversified economy. Agriculture could never succeed on a large scale in New England because the climate prevented a long growing season and the soil was “too rocky by far.” Therefore, New Englanders killed little animals for their furs. Beaver felt hats became a fashion craze back in England, and a steady commerce occurred for ten years before the supply was exhausted. Next, they killed trees. The lumber harvested in New England was a critical commodity in England that by now had largely deforested its island nation (remember all those sheep farms). Both in England and America the lumber was turned into ships which became the key for trade and the origins of the persona known as the Yankee trader. (“Yankee” is of Indian origin when they tried to pronounce “English.”) The trees to ships to trade cycle gave New England an eventual advantage over the economy of the South as we will see all the way until 1865 when the North beat the South in the Civil War (and beyond). What did Yankee traders trade? Answer: food, fish, timber, and livestock which provided the capital to invest in industrialization. Capital really began to collect as New Englanders took on shipping duties for all Americans with the big three: tobacco, molasses, and slaves. Southern tobacco was picked up and shipped to England. On the way home, traders stopped by Africa and picked up slaves. The slaves were sold in the Caribbean and in the southern colonies where traders picked up molasses. The molasses was taken home to New England where another industry distilled it into rum. Ships laden with rum (and wine) went to Africa to barter for slaves, which. . . you get the point of the phrase, “triangular trade.” These constantly revolving products and markets created a dynamic fluidity where only the shrewdest traders prospered. The shrewdest became the richest and their rising wealth encouraged sophisticated financial pursuits like banking and insurance that both required lawyers and other professionals. Guess what was created in America then—cities. The vagaries of early economic development, however, revealed that shrewdness, pluck, canny business sense, and financial genius might come from any class. When only the shrewd survive, social mobility will result just as surely as geographical mobility meant that a colonist would not have to remain in a position of subservience. Be careful, though, because social mobility means that lower classes can rise in America and that upper classes can fall. In other words, if your children are lazy and complacent with mediocrity, your fortune will be lost in one generation. More on social instability later, but first, we’ll look at the southern colonial economy. The colonies of the south were committed to cash-crop economies from 1614 on. Long growing seasons and fertile soil created wealth even if it wasn’t as fast as taking gold from Indians. The crops across the south included tobacco, rice, indigo (used to make blue dye), and sugar. Even though King James I wrote the first English antismoking pamphlet (the “stinking weed” line is his), smoking became a popular vice. So much was produced in America that Englishmen again flooded their markets as 1.5 million pounds were shipped each year. By 1700, the amount exported rose to 38 million pounds per year. English merchants became middle men who transported, stored and marketed the crop to all Europe. In turn, they loaned money to planters who were in constant need of more land since the soil used to produce tobacco was depleted in just a few years. American colonists had to produce more all the time because they made only a small profit on each shipment. Most of the money went to the English (and Dutch) middle men. The need to produce more set in motion a disastrous dynamic for the longterm prospects of southern culture. To acquire more land, southerners had to push Indians west. To clear and work the land, they had to acquire more and more black slaves. While these racial tensions touched off both immediate and latent strife, the need for the land to be under cultivation prevented urbanization, a key to a more sophisticated society. The colonial capital of Virginia, Williamsburg, could boast only 2,000 souls by the American Revolution. By then a northern city like Philadelphia contained over 30,000 people. As General William Tecumseh Sherman would later say, no agricultural country could long compete with an urbanized, mechanized, industrialized country in war. Both the causes and the eventual outcome of the Civil War were set in motion in the earliest days of colonial history.

![USI 5c Social Groups in Colonial America NOTEPAGE[1]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008992443_1-5403a5004a4a567c4d951ad28761d403-300x300.png)