The Decree "Ne temere"

advertisement

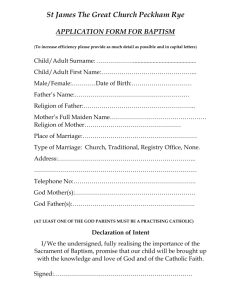

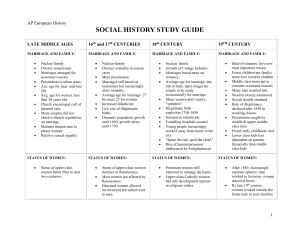

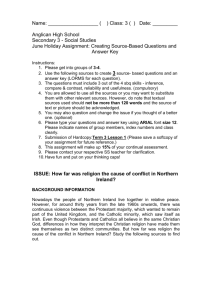

The Economic and Social Review, Vol. 17, No. 1, October, 1985, pp. 11-27 Intermarriage, Conflict and Social Control i n Ireland: The Decree "Ne temere" R A Y M O N D M . LEE University College of Swansea Abstract: T h e decree Ne tenure of 1908 by w h i c h the R o m a n C a t h o l i c C h u r c h has, until recently, governed the marriage of one of its members to someone who is not a R o m a n C a t h o l i c has had attributed to it a n u m b e r of deleterious consequences. T h e origins of the decree, as it has applied to I r e l a n d , are described, as are the events following its promulgation w h i c h c a m e to be referred to as the " M c C a n n case". It is argued that the M c C a n n case c a n be thought of as a " m o r a l p a n i c " . W hile the numerical extent of marriages between R o m a n Catholics and Protestants in Ireland is not great (Lee, 1981), a not inconsiderable social significance attaches to the rules by w h i c h the R o m a n Catholic C h u r c h governs the marriage of one of its members to someone who is not a R o m a n Catholic. I n particular, the papal decree of 1908 k n o w n as "Ne temere" w h i c h , u n t i l quite recently, specified the criteria for recognition by the R o m a n Catholic C h u r c h o f the validity of a " m i x e d marriage", has had attributed to it by a number of com­ mentators a variety of deleterious consequences. It has been argued, for instance, that the attempted extension of R o m a n Catholic control over Catholic-Protestant marriages which .Ne temere repre­ sented was largely responsible for d r i v i n g a wedge between Protestant and R o m a n Catholic in Ireland in the early part of the century (de Paor, 1971, p. 144) and for eroding support for Irish H o m e Rule among Presbyterians (Barkley, 1972). M o r e recently, the Catholic attitude to mixed marriages, as embodied i n the decree, has been taken to represent a c o n t i n u i n g stumbling block to better c o m m u n i t y relations in N o r t h e r n Ireland (Barritt and Carter, 1972, p. 26; Edwards, 1970, pp. 190-196; Rose, 1971, p. 336), as well as being, it is suggested, a major factor w h i c h has contributed to the numerical decline of the Protestant m i n o r i t y in the Republic o f Ireland (Walsh, 1970). I n the present paper an attempt is made, briefly, to outline the development o f R o m a n Catholic rules relating to mixed marriages as they have affected 1 I r e l a n d , p a y i n g particular attention to the relationship between .Ae temere and earlier canonical legislation. T h e events which followed the introduction of JV<? temere i n I r e l a n d are then examined i n some detail, w i t h particular reference to what became k n o w n as the " M c G a n n case", a cause celebre said to have arisen from the application o f the decree. I t is argued that the reaction engendered among Protestants by this case came to take on the character of what Cohen has called a " m o r a l p a n i c " (1972). The Decree " T a m e t s i " One m i n o r confusion concerning Ne temere has arisen because a number of commentators (for instance, Barritt and Carter, 1972; de Paor, 1971) have suggested that the decree was promulgated at the Council of T r e n t . I n fact, the T r i d e n t i n e decree to which they refer was called "Tametsi" and, initially at any rate, it had very little to do w i t h " m i x e d " marriages. Tametsi was designed to regulate the contracting of clandestine marriages ( C u n n i n g h a m , 1964; de Bhaldraithe, 1971), that is, marriages where a couple lived together after having secretly exchanged the marriage" vows w i t h one another. These marriages, although regarded as sinful by the C h u r c h , were still valid (i.e., indissoluble) but they often led to abuses where, for instance, to cite the example supplied by the Council fathers, a m a n could leave his first wife by a valid but secret marriage and then contract a second, public, and i n the eyes of the C h u r c h , adulterous marriage w i t h another woman. After Tametsi, marriages were required to be subject to the "canonical f o r m " ; that is, a marriage to be valid had to be con­ tracted i n the presence o f the parish priest of the place (or his authorised deputy) and two or three witnesses. There was, however, the difficulty that promulgation of the decree i n Protestant countries w o u l d b r i n g the C h u r c h into conflict w i t h a hostile civil power. Fortunately, however, to facilitate its reception by the faith­ ful, the decree was designed to be promulgated parish by parish. I n the event, while Tametsi was speedily implemented i n countries like Spain and Portugal, i n Protestant countries or i n " m i x e d " regions it was either not promulgated at all or came into force only in particular Catholic enclaves (Haring, 1965; de Bhaldraithe, 1971). | 2 I n Ireland, Tametsi was promulgated soon after T r e n t in the two northern­ most ecclesiastical provinces of A r m a g h and T u a m . Its provisions were extended ' T h e concern here is p r i m a r i l y w i t h marriages between R o m a n Catholics a n d members o f other faiths. Protestant i n t e r - d e n o m i n a t i o n a l marriages w i l l not be considered. As w i l l be seen, however, a significant c h a p t e r i n the history o f I r i s h Presbyterianism i n v o l v e d the controversy over the question o f w h e t h e r a Presbyterian minister c o u l d legally m a r r y a Dissenter a n d a m e m b e r o f the Established C h u r c h . 2 Since the i n t e n t i o n here is to correct a m i s i n t e r p r e t a t i o n a n d to set the scene for a discussion ofNe temere, no a t t e m p t is made to discuss i n w i d e r terms the historical d e v e l o p m e n t of ecclesiastical c o n t r o l over m a r r i a g e . (For relevant m a t e r i a l see, for e x a m p l e , D u b y , 1984; Anderson, 1979). to the t h i r d province, Cashel, i n 1775 and to the remaining province, D u b l i n , i n 1778. M e a n w h i l e , Pope Benedict X I V , i n 1741, had decreed that Tametsi was to be taken as not affecting mixed marriages i n Belgium and H o l l a n d , and this declaration, the effect of which was to recognise as valid mixed marriages not celebrated before a Catholic priest, was extended to Ireland i n a Papal rescript of Pius V I dated 19 M a r c h 1785 (Barritt and Carter, 1972, p. 26, Parliamentary Papers 1854-1855, p. 386). T h e exclusion o f mixed marriages from the requirement of being celebrated according to the canonical form, had a particular advantage for the Catholic C h u r c h i n I r e l a n d , i n that i t provided a way of avoiding a point of conflict w i t h the civil law. A l t h o u g h a marriage of two Catholics performed by a Catholic priest was considered to be civilly valid, this was not the case i f the marriage was a mixed one. " B y the A c t 12 G e o . l , c.3, marriages between two Protestants, or a Protestant and a R o m a n Catholic, by a priest or degraded clergyman were declared n u l l and v o i d " (P.P. 1902). Nevertheless, there is some evidence to suggest that mixed marriages celebrated before a Catholic priest were quite common. G i v i n g evidence before a House of Lords Select Committee on the State of Ireland i n 1825, the Reverend Thomas Costello, a Catholic priest from Co. L i m e r i c k , observed that mixed marriages "were very frequent even among the lower orders". Furthermore, he maintained that many of his flock d i d not care to contract a mixed marriage before a Protestant clergyman; the people, he says, are attached to their o w n religion and are quite u n w i l l i n g to legalise their marriages w i t h Protestants, by having the rite performed i n the Protestant church (P.P., 1825, 425). Similarly, the A n g l i c a n Archbishop of D u b l i n stated i n evidence that he believed that such civilly invalid marriages were frequently performed. H e argued, though, that Catholic clergy were particularly eager to assist i n the cele­ bration of mixed marriages because of the possibilities they offered for proselytism. T h e accuracy of such a charge is, of course, difficult to gauge; nevertheless, the illegality of mixed marriages performed by a R o m a n Catholic clergyman had its own particular advantage as far as the R o m a n Catholic hierarchy was con­ cerned. I n 1866, Bishop M o r i a r t y told the R o y a l Commission on the Laws o f Marriage that although he w o u l d prefer the law to be repealed so that Catholic priests might be on the same legal footing as their Protestant counterparts, . . . i f I were to consult m y o w n feelings and convenience I should not wish for any change i n the law because it is very convenient for me, wishing as I do to prevent such marriages to be able to say to parties seeking our ministration, ' N o , the marriage w i l l not be valid i n law and I shall be sub­ jected to a severe penalty . . . ' (P.P., 1867-8, 104). I n any event, the Commission recommended that the law should be changed i n this respect, w h i c h it was i n 1870. T h e C h u r c h law, w i t h respect to validity, remained unchanged however u n t i l the promulgation of Ne temere in 1908. I t is i m p o r t a n t to make use of the phrase " w i t h respect of v a l i d i t y " i n this con­ text because, as we shall see, apart from a brief r u l i n g on the proper form for con­ tracting sponsalia (espousals), Ne iemere d i d not directly concern itself w i t h any aspect of the C h u r c h law other than validity. Thus, Ne temere d i d not, as some writers (especially Edwards) have claimed, constitute an innovation whereby a couple about to enter a mixed marriage were required to promise to baptise and educate any ch ildren of the marriage as R o m a n Catholics. This requirement, i n fact, dates from the eighteenth century (Connick, 1960; de Bhaldraithe, 1971; Esmein, 1891), though there are reasons to believe that the promises were not always sought i n Ireland. 3 Bishop Doyle, R o m a n Catholic bishop of K i l d a r e and L e i g h l i n , when asked by the Select Committee on the State of Ireland mentioned earlier whether there were any prohibitions deriving from the C o u n c i l of T r e n t on Catholics m a r r y i n g Protestants, replied, correctly for the reasons we have seen, that there had been no legislation on the matter at that Council. H e then went on to say that mixed marriages were still regarded as valid i n the eyes of the C h u r c h even if celebrated before a Protestant minister, and that no censure was incurred by the Catholic party if the children of a mixed marriage were brought up as Protestants. Boyle was quitei emphatic on this point; Catholic clergymen, he maintained, only advised, rather t h a n insisted, that the children be brought up as Catholics. A r c h ­ bishop M u r r a y , Catholic Archbishop of D u b l i n , on the other hand, conceded that not only d i d the Catholic C h u r c h dislike mixed marriages taking place, but whenever we allow them it is. always as far as I know w i t h the condition that the children o f the marriage are to be educated i n the Catholic religion (P.P., 1825, 265). ! i W e i g h t is added to this by the evidence o f the Reverend M o r t i m e r O ' S u l l i v a n , an Anglican clergyman, who testified that he had k n o w n cases where the rites o f the Catholic C h u r c h had been withheld from a Catholic involved i n a mixed marriage who had allowed the children of the marriage to be brought up as Protestants (P.P., 1825,459). Certainly, Bishop M u r r a y ' s state­ ment quoted above is hardly unequivocal i n contrast to the evidence of his Anglican counterpart who claimed the practice to be widespread, . . . and in that way very materially, and perhaps principally the number of R o m a n Catholics has of late years increased, for it hardly ever fails even among the lower orders that the Protestant yields, especially i n the case ' E d w a r d s ' somewhat tendentious account o f w h a t he calls the " M a r r i a g e L a w o f 1908" seems to have been.derived f r o m a.reading o f the Code o f C a n o n L a w issued i n 1917, rather t h a n f r o m the text o f Ne temere. where the R o m a n Catholic is the female, and the children are w i t h very few exceptions brought up as R o m a n Catholics (P.P., 1825, 421). Clearly, though, the promises were not extracted i f the marriage was per­ formed by a Protestant clergyman, while Edwards (1970) has suggested that the custom i n I r e l a n d i n the nineteenth century was rather for the male children of a mixed marriage to be brought up i n the father's religion while girls were brought up to follow the mother's faith. M o r t i m e r O ' S u l l i v a n , when asked about this particular practice by the Select Committee, replied that he was not familiar w i t h it, a d d i n g that he thought it unlikely that the priests w o u l d condone it. However, there is evidence to suggest that the practice was k n o w n throughout Europe, and that it was even defended by some Catholic theologians, presum­ ably b o w i n g to local custom. U l t i m a t e l y , though, the practice and its apologists were condemned by Benedict X I V (Connick, 1960). Edwards (1970, p. 190) argues that the custom of raising boys to follow the father and girls to follow the mother was related in some way to a pattern of hypergamous marriage. As one cannot assume that the social relations between Protestants and R o m a n Catholics were duplicated elsewhere i n Europe, this seems not altogether plaus­ ible. One can note, however, that such a custom w o u l d be consistent w i t h the division o f labour i n peasant families and would have the advantage of ensuring the c o n t i n u i t y of land inheritance w i t h i n the religious group. Whatever the reasons l y i n g behind the custom Edwards describes, O ' S u l l i ­ van's remark on the likely opposition of the priesthood to the practice seems to be borne out by the statement o f the Synod of Thurles i n 1850 r e m i n d i n g priests of the necessity of o b t a i n i n g the promises (de Bhaldraithe, 1971). W i t h the pro­ mulgation of Ne temere, further weight was added to this requirement but i n an indirect fashion. Ne temere made the presence o f a priest and two witnesses a necessary c o n d i t i o n of the validity of any marriage involving a Catholic: O n l y those marriages are valid w h i c h are contracted before the parish priest or O r d i n a r y (bishop) of the place or a priest delegated by either of , these, and at least two witnesses . . . Further, and here is the only mention of mixed marriages: T h e same laws are b i n d i n g on the same Catholics as above, if they contract sponsalia or marriage w i t h non-Catholics baptized or unbaptized, even after a dispensation has been obtained from the impediment mixtis religionis or disparitus cultus; unless the H o l y See decree otherwise for some particular place or region. (P.P., 1912-13, app. X I V ) . 4 ''Mixtis religionis is the m a r i t a l i m p e d i m e n t i n v o l v e d i n a proposed m a r r i a g e between a C a t h o l i c and a baptised n o n - C a t h o l i c . W h e r e the n o n - C a t h o l i c has not been baptised, the i m p e d i m e n t is one ofdisparitus cultus. ( I t is possible to give a n u m b e r of sources for the text ofJV« temere b u t today the X l V t h A p p e n d i x to the R e p o r t o f the R o y a l C o m m i s s i o n on D i v o r c e , 1912-13 is likely to be the most convenient place to find the official E n g l i s h t r a n s l a t i o n . T h e decree itself is d a t e d 2 A u g u s t , 1907 b u t d i d not corrie i n t o general effect u n t i l Easter Sunday, 19 A p r i l , 1908.) T h e effect o f this, however, was to make obligatory the promises regarding children because, as de Bhaldraithe points out, mixed religion, although an impediment, could not of itself render a marriage invalid. However, a priest w o u l d not perform such a marriage u n t i l a dispensation from the impediment had been granted, and this a bishop w o u l d not do u n t i l the promises had been given, "So, in practice, the promises became necessary for v a l i d i t y . " (de Bhaldraithe, 1971 — emphasis added). The Aftermath of "Ne temere" in Ireland: The McCann Case The provisions of Ne temere had been criticised by the Synod of Bishops o f the C h u r c h of I r e l a n d soon after its promulgation. T h e decree made little public impact u n t i l 1910, however, when it attained a good deal of notoriety as a result of what became k n o w n as the " M c C a n n case". T h e public first became aware of the M c C a n n case i n November 1910 when a letter from the Rev. W i l l i a m Corkey, M i n i s t e r of Townsend Street Presbyterian C h u r c h i n Belfast, was pub­ lished i n the local press. [ T h e text of this letter can be found in Corkey's autobio­ graphy (Corkey, 1961, p. 151).] M r Corkey's letter concerned the plight o f M r s Agnes M c C a n n , a member of his congregation. Agnes M c C a n n . the letter stated, had married her husband Alexander, a R o m a n Catholic, in a Pres­ byterian ceremony some years before Ne temere came into effect. T h e couple agreed at the time of their wedding that they should attend their respective churches, and the marriage itself was a happy one. Eventually, however, the letter went on, M r . M c C a n n ' s priest came to the house and told the couple that the marriage was invalid as a result of the change in canon law brought about by Ne temere.. M r . M c C a n n asked his.wife to remarry in a Catholic ceremony and when she refused, began to ill-treat.her. Some time later, he deserted her, taking w i t h h i m the couple's two children and, later, all of their furniture. T h e priest, who regarded M r s M c C a n n as having been l i v i n g in sin, would do nothing to help her, leaving her destitute and w i t h o u t her children. M u c h of what followed is usefully summarised by Corkey himself in two pub­ lished accounts of his role i n the affair, the one i n a pamphlet (Corkey, 1911) pro­ duced by the E d i n b u r g h K n o x C l u b at the height of the controversy, in which is reproduced his address to a protest meeting in E d i n b u r g h , and the other in a chapter of his autobiography w r i t t e n many years later (Corkey, 1961). Despite the gap o f fifty years, the latter is especially valuable since it lists those who spoke at the major protest meetings and records their contributions, apparently on the basis o f minutes taken at the time. As he records, Protestant opinion in I r e l a n d was incensed by the revelations contained in M r Corkey's letter. Soon after it appeared, a special meeting of the 5 5 C o r k e y h a d m a n y ties to E d i n b u r g h . H i s m o t h e r h a d been b o r n i n the city a n d he h a d studied D i v i n i t y at E d i n b u r g h U n i v e r s i t y . Belfast Presbytery was held at which a committee was established to support M r s M c C a n n , to publicise her case and to help her obtain redress. I n a short time the committee had organised a large-scale protest meeting i n Belfast at which were represented a l l the major Protestant denominations in Ireland. Similar protest meetings were soon held i n D u b l i n , E d i n b u r g h , at three venues in L o n d o n and in a number of other towns and cities. A t the same time , M r s M c C a n n was advised to appeal to the L o r d Lieutenant of Ireland to initiate a police search for her children. W h e n the L o r d Lieutenant refused to intervene in what he regarded as a civil matter, the affair was raised in the House o f Commons by a Unionist member for D u b l i n University, J. H . C a m p b e l l (later L o r d Glenavy) and in the Lords by L o r d Donoughmore. W h a t had begun as a domestic imbroglio very quickly became what Stanley Cohen has termed a " m o r a l panic". 6 The McCann Case as a Moral Panic M o r a l panics can be thought o f as collective expressions o f moral indignation which arise when a " c o n d i t i o n , episode, person or group of persons emerge to become defined as a threat to societal values and interests" (Cohen, 1972, p. 9). Cohen originally used the term " m o r a l panic" i n a study w h i c h traced societal reactions to the M o d s and Rockers phenomenon of the 1960s. I n the present con­ text it may seem somewhat anomalous to introduce a parallel w i t h the societal condemnation o f riotous young people. I n w h a t follows, however, what is i m p o r t a n t is the suggestion i n Cohen's work that the arousal of public indigna­ tion may take on a characteristic temporal dynamic while at the same time generating a set o f negative stereotypical conceptions which become attached to particular events, persons or groups. Cohen notes that the expressions o f indignation typical o f moral panics become generated on the basis of an account or " i n v e n t o r y " o f what has happened whose source in the media or in the " m o r a l enterprise" (Becker, 1963) of particular individuals is not usually a disinterested one. The novel or pre­ viously unnoticed social phenomenon comes to widespread public attention in circumstances where pressures to ensure newsworthiness or to gain a sympath­ etic public hearing produce a tendency for matters to be presented i n a stylised and dramatic way. T y p i c a l l y , when this happens, particular aspects or elements of the situation, like the clothing styles of the Mods and Rockers, are singled out for negative symbolisation. This in t u r n serves as a basis for labelling those to w h o m the symbols may be attached as deviant and in need of sanction. T h e b r i n g i n g into being of an inventory which highlights an apparently serious and problematic new development gives rise, Cohen suggests, to a public concern both for interpretation and for control. A t this stage, therefore, the ''It should be emphasised that the w o r d " p a n i c " is used here i n a technical sense a n d carries no derogatory c o n n o t a t i o n whatsoever. attention focussed on the inventory begins to lessen. T h e concern now is, on the one hand, to assimilate the object of the m o r a l panic into a pre-existing inter­ pretative scheme w h i c h makes sense; of what has happened, and, on the other, to do something about it. Explanations and prognostications concerning the nature, causes and likely effects of the new phenomenon, and which allow its evaluation i n terms of dominant values, are now developed to add to the stock of negative imagery and stereotype already i n existence. N o r m a l l y , it is at this j u n c t u r e , too, that the apparent ineffectiveness of existing social controls to deal w i t h the emergent phenomenon is revealed. Further and more effective social control is sought through calls for the strength­ ening o f existing control measures and through the increased intervention of control agencies targeted on those social types already marked out by negative symbolisation. T h e final outcome of the m o r a l panic depends, i n Cohen's view, on what results from this enhanced control effort. I n the case of the Mods and Rockers, for example, intensive social control was actually effective i n extinguishing the behaviour which led initially to the m o r a l panic. A n alternative possibility, how­ ever, is that the original deviance becomes " a m p l i f i e d " as those marked out by the m o r a l panic develop subcultural forms organised around the contingencies produced through the application of social control (cf. Y o u n g , 1971). T h e legacy of the m o r a l panic i n this case is the permanent inclusion of a new social type i n society's catalogue of folk-devils. One difficulty w i t h Cohen's model, w h i c h he himself was later to acknowledge (1980), is that it deals p r i m a r i l y w i t h reactions to particular events while saying relatively little about the context out of which a m o r a l panic arises. I n the con­ text of the McCiann case, one i m p o r t a n t backdrop to the whole affair which should be borne i n m i n d is that the issue of m a r i t a l invalidity was a particularly emotive one for Presbyterians in Ireland. I t had only been just over sixty years earlier, i n 1845, that Presbyterian ministers had become able i n civil law to conduct a marriage ceremony between a Presbyterian and a member of another denomination. Indeed, the legal right to j o i n together t w o Presbyterians i n marriage had only been granted to Presbyterian clergy towards the end of the eighteenth century. A l t h o u g h they had been granted indemnity from prosecution i n 1737, before this time Pres­ byterians who had not had their marriages solemnised before a minister of the Established C h u r c h could face proceedings i n ecclesiastical courts, a procedure w h i c h carried w i t h it an implication that those who regarded themselves as pro­ perly and respectably married were merely l i v i n g i n a state of cohabitation A further difficulty w i t h Cohen's model is that it depends for its effectiveness on an ironic comparison i n which the exaggerated and stylised reaction to an 7 7 I a m extremely grafeful to an a n o n y m o u s referee for the i n f o r m a t i o n c o n t a i n e d i n this p a r a g r a p h . event can be checked against " w h a t acutally happened". T h a t Cohen was able to do precisely this i n his study of the M o d s and Rockers adds considerably to the persuasiveness o f his argument. Such a comparison is, of course, m u c h more difficult to accomplish w i t h non-contemporary material and i n situations such as the M c C a n n case where, as described later, one o f the groups had — unlike the Mods and Rockers — the power and the interest to develop and propagate a counter-inventory of what had happened. O n the facts available, it is not possible to say whether or not M r Corkey's account o f M r s M c C a n n ' s tribulations was distorted or exaggerated. One, of course, cannot doubt M r Corkey's sincerity, though it is likely that even if there was no conscious exaggeration, he w o u l d undoubtedly have wanted to put the situation i n which M r s M c C a n n found herself in the best possible light. W h a t is clear is that the alleged source of M r s M c C a n n ' s plight — the decree Ne temere — and its perpetrator, the R o m a n Catholic C h u r c h , were soon seen i n a negative, stereotypical and even l u r i d way. W h a t had happened to M r s M c C a n n was almost invariably interpreted on the basis of an assertion that the Catholic C h u r c h was an aggressively domineering institution. T h i s view, for example, was forcefully put by one o f Corkey's presbytery colleagues, who i n proposing a m o t i o n o f support for M r s M c C a n n , declared "the claim o f that church always has been to control the i n d i v i d u a l , the home, the school, the n a t i o n " (Corkey, 1961, p. 154). I n this light, the decree Ne temere was seen to represent an attempt by the Catholic C h u r c h to extend its domination. T h e McCanns were legally m a r r i e d i n British law. By declaring the marriage n u l l and void as a result of the decree, the Catholic C h u r c h , the argument went, was t r y i n g to undermine that law. As Corkey (1911, p. 15) p u t it i n E d i n b u r g h , This decree challenges the supremacy o f British law. I hold i n m y hand a marriage certificate bearing the seal o f the British Empire, and recording the marriage of Alexander M c C a n n and Agnes Jane Barclay. T h i s certifi­ cate declares that, according to the law o f Britain, these two are husband and wife. T h i s Papal decree says their marriage is " n o marriage at a l l " . W h i c h law is going to be supreme i n Great Britain? F r o m the Protestant point of view, there was i n this challenge an additional and sinister significance. T h e Pope was both head o f the R o m a n Catholic C h u r c h and the ruler o f a sovereign state, m a k i n g the Catholic C h u r c h b o t h a religious body and a foreign power. I n consequence, the operation of Ne temere could be seen as advancing the interests of that foreign power to the detriment of the rights and privileges due to the population of Ireland as subjects of the British Crown. A n argument o f this kind gave the opponents o f the decree an o p p o r t u n i t y they were not slow to exploit to appeal to xenophobia and to Empire loyalism. Speaking i n D u b l i n , J. H . Campbell called the promulgation of the Ne temere " a n act of intolerable aggression by a foreign power" (Corkey, 1961, p. 164). T h e audience at the protest meeting in Belfast was asked by D r Crozier, the C h u r c h of I r e l a n d Bishop of D o w n , Connor and Dromore, whether the sacred vows of marriage "are to be repudiated at the b i d d i n g of a foreign Pontiff' and heard the M o d e r a t o r of the General Assembly of Ireland, Rev. D r J. H . M u r p h y , tell t h e m to "demand that the benefits and securities which we enjoy as British subjects under British law shall not be stolen from us by any self-constit­ uted ecclesiastical t y r a n n y " (Corkey, 1961, p. 157). A l o n g w i t h the challenge it was said to pose to the civil liberties of British sub­ jects, Ne temere was also regarded as a threat to the home. T h e m o t i o n condemning the decree at the protest meeting held in Belfast, for example, described Ne temere as "a direct incentive to the breach of the marriage v o w " (Corkey, 1961, p. 158). Corkey, too, skilfully combined the threat to the family w i t h the themes of E m p i r e and foreign d o m i n a t i o n in his address to the E d i n b u r g h meeting. Ne temere, he claimed (1911, p. 14), was a danger to the C o m m o n w e a l t h "because it strikes at the home", and he went on, i I t w i l l affect the peace and harmony of thousands of homes. We believe w i t h L o r d Rosebery that "the roots of empire are i n the home", and if the decree of a. foreign power can come into a free British home and break it up, that decree becomes a menace to the State. H a v i n g developed an account of what had happened and an interpretation of its origins and implications based on ideas about the domineering intent o f the Catholic C h u r c h and the machinations o f the Pope as the leader o f a foreign power, Protestants were still faced ^with the task of taking effective action against the decree. I n accounting for the transition from interpretation to remedy in the case of the Mods and Rockers, Cohen (1972, C h . 4) points to the importance of two elements: "sensitisation" and the character of what he calls the "official con­ trol c u l t u r e " . Sensitisation refers to the development of a perception that the novel social phenomenon causing concern is not an isolated instance but is in reality a l l around, while the "official control c u l t u r e " may be thought of as the norms, values and w o r k i n g practices of the official agents of social control. Cohen notes that such agents were quickly and decisively mobilised against the Mods and Rockers because of the congruence between the official control cul­ ture and the conventional stereotypes which the Mods and Rockers evoked. Protestant o p i n i o n in Ireland very quickly became sensitised to the operation of Ne temere. Commentators hostile: to the decree indeed took pains to stress that the M c C a n n case was not a single, isolated incident. M a n y of those who spoke at public meetings, including Corkey himself, indicated that they had at least i n ­ direct knowledge of other cases. D r I r w i n , for example, told the Presbytery meeting that he " c o u l d add to M r Corkey's story one from his o w n experience". One of the speakers at the Belfast protest meeting had received a communication earlier i n the day from "a well-informed observer i n Co. D o w n that two cases of practically the same procedure had taken place i n a well-known locality there" (Corkey, 1961, p. 160), while the Archbishop of D u b l i n was able to tell the audi­ ence at the protest meeting i n the city that he too had had a further case brought to his attention. His colleague, the Archdeacon of Ferns, managed neatly to stress the impact of the decree while m i t i g a t i n g any possible charge that addi­ tional cases were few i n number. I n his view many people were suffering because of Ne temere but these cases d i d not come to light because those involved were afraid to come forward. A rash o f cases similar to the M c C a n n s ' was, i n fact, reported at the time, including a number i n England, and a year later cases on the M c C a n n model, such as that involving the alleged abduction of the daughters of a mixed marriage i n K i l m u r r a y , Co. Cork, were still to be seen i n the press. O n e suspects that an element o f exaggeration was at work here since many of the reports were at second hand. F u r t h e r , i t is not, of course, impossible that what was being pro­ duced was a self-fulfilling prophecy. T h e publicity surrounding the M c C a n n case may have encouraged Catholic clergy to seek out those affected retrospect­ ively by the decree w i t h more diligence than they m i g h t otherwise have done on a simple reading o f the original p r o m u l g a t i o n w i t h its emphasis on sponsalia. T h e result of a self-fulfilling prophecy or not, the threat posed hyNe temere was clearly apparent, at least i n Protestant eyes. Moves to deal w i t h that threat, how­ ever, were m u c h less readily forthcoming than the campaigners could have wished, i n the first instance because conditions existed which permitted a chal­ lenge to the whole basis upon which the m o r a l panic had been developed. T h e ability of a group to resist attempts at stigmatisation and the application of punitive sanctions lies i n its size, level of organisation and relative power (Lofland, 1969, pp. 13-15). I f one takes the Mods and Rockers, for example, it is clear that they were, i n relative terms, small i n number and almost completely lacking i n any real organisational structure. I n common w i t h other young people, they had little i n the way of economic or political power w i t h which to exercise any countervailing influence over the control apparatus, nor d i d they possess means to propagate information which might have modified or falsified the negative and largely exaggerated stereotypes o f them which were being pro­ pounded. Indeed, to the contrary, where Mods and Rockers d i d have direct access to the media, it was in contrived situations which could be exploited to justify the worst fears upon which the m o r a l panic had been based (Cohen, 1972, pp. 140-141). Catholics i n I r e l a n d i n the period of the M c C a n n case, on the other hand, formed, as they still do, a sizable and well-organised group w i t h their o w n repre­ sentatives and w i t h access to the media. I t was thus possible for Catholic opinion leaders to offer a counter-inventory of what had happened and a counter-inter- pretation of w h y the M c C a n n case had come to the public view. I n this situation, the universality o f condemnation of the k i n d w h i c h greeted the Mods and Rockers and the inter-penetration o f conventional stereotypes and the official control culture was much less likely to emerge. Instead, the expression of moral indignation became co-extensive w i t h pre-existing lines of social and political differentiation. T h e decree Ne temere and its alleged consequences became no longer the object solely of a crusade but of a controversy. The Catholic counter-inventory w i t h its attendant counter-interpretation is most concisely found i n the replies made by Nationalist M P s when the M c C a n n case was raised i n the House of Commons. Joseph Devlin, M P for West Belfast, produced a letter i n the House w h i c h he claimed was from Alaxander M c C a n n . As read later i n the debate by J o h n D i l l o n , this described the McCanns' marriage as having been unhappy. I t had been beset by difficulties produced, it was said, by M r s . M c C a n n ' s aggressiveness and her interference w i t h the pract­ ice of M r M c C a n n ' s religion. As the letter put it (House of Commons, col. 193): . . . there was never a day passed w i t h o u t a dispute. For instance, she w o u l d have meat ready for me on Fridays. She would put back the clock and make me late for Mass. She ridiculed the priest and religion, cursed the Pope and sang hymns a l l day.' M r M c C a n n had left, the letter said, because he had found the situation intoler­ able. H e specifically denied, however, that his priest had ever urged h i m to desert his wife. D e v l i n further claimed to know the: real significance behind the M c C a n n case. D u r i n g his campaign, he alleged, posters had gone up i n his constituency which said, " W i l l you vote for D e v l i n and have your Protestant children kidnapped by the Priest?" I n his view, the whole affair had been manipulated quite simply and cynically for political ends. A d d e d weight was given to this position i n Nationalist eyes by an important weakness i n M r s M c C a n n ' s story. She consistently refused to name the priest who had visited the home w i t h news of the retrospective effect of Ne temere. D e v l i n produced statements from the priests i n M c C a n n ' s parish denying a l l of M r s M c C a n n ' s charges and threatening legal action against anyone who named any o f them publicly as being the priest i n the case. Protestant reluctance to take up this challenge was taken as evidence o f the unsoundness of their case. Given the existence of inventory and counter-inventory, interpretation and counter-interpretation, the response of the official control apparatus to a moral panic becomes problematic. I n this situation the obtaining of an authoritative resolution to a controversy lies, it is probably not too cynical to suggest, in the relative power of each faction to align the official control structure to its version of the affair. T h e j u n c t u r e at which the M c C a n n case took place put Protestants at a disadvantage in this regard. Since 1908 (ironically the year in which Ne temere had been promulgated) the support of the Irish Nationalists at West­ minster had allowed the L i b e r a l Government to remain i n office, an advanta­ geous parliamentary position for the Nationalists which had been enhanced by the General Election of December 1910 (Lyons, 1973, p. 269). T h e government of the day was, therefore, relatively unsusceptible to pressure identified w i t h the Unionist cause. Even despite the large-scale protest campaign w h i c h had been waged against Ne temere and the evident feeling which the issue had aroused among Protestants, the government d i d not retreat from the position originally taken by the L o r d Lieutenant. Birrell, the Chief Secretary for Ireland, reiterated in' the House of Commons that the matter was a civil one over which the authorities had no direct j u r i s d i c t i o n and affirmed that, although the police had been permitted to try to establish M r M c C a n n ' s whereabouts, the C r o w n authorities were refusing to become any more deeply involved i n the case. Birrell's speech to the House of Commons actually supplies an example of the way i n w h i c h the official control culture can be used to t h w a r t attempts to mobilise the official control agencies i n support of a m o r a l panic. I n i t he ident­ ifies the issue as being largely concerned w i t h the specific plight of M r s M c C a n n . Not only d i d this avoid the wider issues which the decree undoubtedly raised, but it was an attempt to encourage the view that a strict adherence to existing legal norms was sufficient to deal w i t h the problem w h i c h had arisen. Birrell argued that M r s M c C a n n could have obtained speedy and effective redress by an application to the C o u r t of Chancery. Since M r s M c C a n n ' s advisers had not recommended to her this simple remedy but had preferred instead the more public and politically more useful device of an appeal to the L o r d Lieutenant, they stood condemned, Birrell contended, of p u t t i n g political expedience before M r s M c C a n n ' s best interests (House of Commons, cols. 161-163). T h e cam­ paign against Ne temere was, therefore, merely a manoeuvre by Unionists to w h i p u p feeling against H o m e Rule and i n this light was not to be taken as a genuine basis for concern about the decree. Consequences of the McCann Case I n the short t e r m , it appears then as if those who opposed .Al? temere were, on the whole, unsuccessful i n dealing w i t h the effects o f the decree. I n the case o f M r s M c C a n n herself this was noticeably so, for although donations from well-wishers and the proceeds o f collections at protest meetings saved her from destitution, she remained unable to recover her c h i l d r e n . Moreover, there seems never to have been any prospect that the furore over the M c C a n n case w o u l d lead to the 8 8 I t seems that i n later years M r s M c C a n n d i v o r c e d her husband a n d r e m a r r i e d . A n a t t e m p t was made to trace her i n o r d e r to i n t e r v i e w her a b o u t the case, b u t she p r o v e d to have d i e d a few years earlier. !! i T H E ECONOMIC A N DSOCIAL REVIEW w i t h d r a w a l or modification of the decree or that it was damaging to British rela­ tions w i t h the H o l y See. Because it did not result i n an alignment of the author­ ities w i t h those who opposed Ne temere, the wave of m o r a l indignation aroused by the M c C a n n case must be thought of as a failed m o r a l panic. By other criteria, however, the m o r a l panic induced by the M c C a n n case m i g h t be j u d g e d a success. As Becker (1963), Cohen (1972, pp. 139-143) and others point out, those engaged i n m o r a l enterprise have often, i n fact, a vested interest i n the continued existence of that which they decry. Certainly, had the McCanns' domestic difficulties been successfully resolved or the impact of the decree been lessened by government action or a change o f heart at the V a t i c a n , the case w o u l d not have served the Unionist cause nearly so well as it i n fact d i d . This was so for t w o reasons. T h e first was that the p r o m u l g a t i o n and enforce­ ment of Ne temere were seen as actions which decisively marked off the Catholic C h u r c h from other Christian bodies. T h e judgement o f the Presbyterian minister who seconded the resolutions put forward at the protest meeting i n Belfast was emphatic, for example: "Between all forms of Protestantism repre­ sented on this platform tonight and Romanism there is a dark gulf fixed" (Corkey, 1961, p. 160). N o w , this was p a r t l y based on the recognition that the decree put into question the validity of all marriage rites performed by nonR o m a n Catholic clergy. I f a marriage performed before a Protestant minister was n u l l and void because one of the partners was a R o m a n Catholic, was not a marriage between t w o Protestants, which used exactly the same form, also invalid? Partly, however, the distinction between Catholics and Protestants was also tacitly d r a w n on the basis of Protestant m o r a l superiority. O n l y the R o m a n Catholic C h u r c h , i t was implied, was capable of the kind of action Ne temere had produced, the dismemberment of a family and r o b b i n g a mother of her children. " T h e spirit that could break up a happy home", said D r . M u r p h y , " . . . is capable of any e n o r m i t y " (Corkey, 1961, p. 157), while Corkey rather dramat­ ically announced, "the men that w o u l d defend this cruel deed w o u l d b u r n (Protestants) if they had the power" .Ne temere was, as J. M . Barkley (1972) points out, the first occasion on which all of the Protestant churches in I r e l a n d took j o i n t and concerted action to preserve their interests. I t is likely that the sense of m o r a l superiority w h i c h the campaign engendered was also an important ele­ ment i n the forging o f a supra-denominational identity among non-Roman Catholics i n Ulster. Secondly, Protestants became convinced that Ne temere was a foretaste of what might be expected if H o m e Rule were to be granted to an Ireland in which con­ trol w o u l d be i n the hands of a Catholic Nationalist party. (For reviews of the period, see Stewart (1967) and Lyons (1973)). Never expressed openly at the pro­ test meetings w h i c h were proclaimed to be non-political (see, e.g., Corkey's opening remarks at E d i n b u r g h (1911, p. 3)), the point was, nevertheless, made explicit by U n i o n i s t politicians and the Press. Said Campbell i n the House, A t least this case o f M r s M c C a n n is a solemn w a r n i n g to those o f us in Ire­ land who feared such results (of Nationalist control i n Ireland) and I can assure this house that it has strengthened the unalterable determination of Loyalists and Protestants in the c o u n t r y . . . to retain what they believe to be the only guarantee for the continued enjoyment of their civil rights . . . (House o f Commons, col. 158). while the Northern Whig put the argument in a somewhat blunter fashion: T h e case sheds a flood of light upon what w o u l d happen i f the C h u r c h of Rome were to be established in Ireland, as under H o m e Rule it would be (6 January, 1911). T o quote Barkley again: T h e prominence o f the Ne temere decree and the M c C a n n case in the speeches of the period and in Presbytery discussions points to this being the reason for the switch to almost total opposition to H o m e Rule. T h e vote (at the General Assembly) being 921 against and 43 for — a very different situation from that twenty years earlier. A p a r t from its political impact, the M c C a n n case had consequences for those in subsequent years who contemplated a Protestant-Catholic marriage. I n the first place, although there is no direct evidence w i t h which to support the proposition, it is likely that in the wake of the publicity surrounding the M c C a n n case social control of religious intermarriage was intensified. Protestant parents seeking to dissuade a son or daughter from marriage w i t h a R o m a n Catholic now had, in the M c C a n n case, a powerful cautionary tale, while Catholic priests, to echo a point made earlier, were not alerted to the necessity for ensuring that " m i x e d " marriage took place i n a Catholic ceremony. Secondly, a Catholic-Protestant couple wishing to m a r r y could no longer leave the site of the ceremony to custom or to personal preference. Instead, they faced decisions about the formal validation of their relationship as a major contingency in court­ ship and w i t h the prospect, whatever their decision, of displeasing one sideor the other. As is shown elsewhere (Lee, 1981), in this respect at least the impact of the Ne temere decree and the Protestant reaction generated by the M c C a n n case retains a contemporary significance. 9 I hope i n the near future to undertake a more detailed a n d extensive study o f the M c C a n n case. 9 I REFERENCES A N D E R S O N , M I C H A E L , 1979. " T h e Relevance o f F a m i l y H i s t o r y " , i n C . C . H a r r i s (ed.), The Sociology of the Family: New Directions for Britain, Keele: Sociological R e v i e w M o n o g r a p h 28. B A R K L E Y , J . M . , 1972. St. Enoch's Congregation, Belfast: C e n t u r y Services L i m i t e d . B A R K L E Y , J . M . , 1975. " T h e Presbyterian C h u r c h i n I r e l a n d a n d the G o v e r n m e n t o f I r e l a n d A c t (1920)", i n D e r e k Baker (ed.), Church, Society and Politics, Studies i n C h u r c h H i s t o r y , V o l . 12, O x f o r d : Basil B l a c k w e l l . B A R R I T T , D E N I S P. a n d C H A R L E S F . C A R T E R , 1972. The Northern Ireland Problem: A Study in Group Relations, L o n d o n : O x f o r d U n i v e r s i t y Press, 2 n d ed. B E C K E R , H O W A R D S., 1963. Outsiders: Studies in the Sociology of Deviance, N e w Y o r k : T h e Free Press. C O H E N , S T A N L E Y , 1972. Folk Devils and Moral Panics: The Creation of the Mods and Rockers, London: M a c G i b b o n and Kee. C O H E N , S T A N L E Y , 1980. " I n t r o d u c t i o n to the N e w E d i t i o n " , i n Folk Devils and Moral Panics, 2 n d ed., O x f o r d : M a r t i n Robertson. C O N N I C K , A L F R E D J . , 1960. " C a n o n i c a l D o c t r i n e C o n c e r n i n g M i x e d M a r r i a g e s — Before T r e n t a n d D u r i n g the Seventeenth a n d E i g h t e e n t h Centuries', The Jurist, V o l . 220, N o . 3, p p . 295-326; V o l . 4, p p . 368-418. C O R K E Y , R E V . W I L L I A M , 1911. The McCann Mixed Marriage Case, E d i n b u r g h : T h e K n o x Club. C O R K E Y , R E V . W I L L I A M , 1961. Glad Did I Live, Belfast: C e n t u r y Services L t d . C U N N I N G H A M , T . P . , 1964. " M i x e d M a r r i a g e s i n I r e l a n d before Ne temere", Irish Ecclesiastical • Record, V o l . 1 0 1 , p p . 5 3 - 5 6 . D E B H A L D R A I T H E , E O I N , 1971. " T h e C h i l d r e n o f an I n t e r - C h u r c h M a r r i a g e " , M o o n e , Co. Kildare: Unpublished M S . DE 2nd PAOR, LIAM, 1971. Divided Ulster, Harmondsworth, Middlesex.: P e n g u i n Books, ed. D U B Y , G E O R G E S , 1984. The Knight, the Lady and the Priest, L o n d o n : A l l e n L a n e . E D W A R D S , O W E N D U D L E Y , 1970. The Sins Of Our Fathers, D u b l i n : G i l l a n d M a c m i l l a n . E S M E I N , A . , 1891. Le Manage en Droit Canonique, Paris: Larose et Forcel, V o l . 2. H A R I N G , B E R N A R D , CSSR., 1965. Marriage in the Modern World, C o r k : M e r i c a . L E E , R A Y M O N D M . , 1981. Interreligious Courtship and Marriage in Northern Ireland, P h . D . thesis, U n i v e r s i t y of E d i n b u r g h . L O F L A N D , J O H N , 1969. Deviance and Identity, E n g l e w o o d Cliffs, N . J . : P r e n t i c e - H a l l . L Y O N S , F . S . L . , 1973. Ireland Since The Famine. L o n d o n : C o l l i n s / F o n t a n a . R O S E , R I C H A R D , 1971. Governing Without Consensus: An Irish Perspective, L o n d o n : Faber a n d Faber. S T E W A R T , A . T . Q . . , 1967. The Ulster Crisis, L o n d o n : Faber a n d Faber. WALSH, BRENDAN M . , 1970. Religion and Demographic Behaviour in Ireland, D u b l i n : The E c o n o m i c a n d Social Research I n s t i t u t e , Paper N o . 55. Y O U N G , J O C K , 1971. " T h e R o l e o f the Police as amplifiers o f Deviance, Negotiators of R e a l i t y a n d Translators of Fantasy: Some Consequences o f o u r Present System o f D r u g C o n t r o l As Seen i n N o t t i n g H i l l " , i n Stanley C o h e n (ed.), Images of Deviance, H a r m o n d s w o r t h , M i d d l e s e x : P e n g u i n Books. PARLIAMENTARY PAPERS 1825 IX Select C o m m i t t e e o n the State o f I r e l a n d 1854-5 XXII M a y n o o t h Commission. 1867-8 XXXII R o y a l C o m m i s s i o n o n the L a w s o f M a r r i a g e . 1902 XLIX 3 4 t h R e p o r t o f the D e p u t y K e e p e r o f the P u b l i c Records i n I r e ­ l a n d , A p p e n d i x I I : " R e p o r t by M r . H e r b e r t W o o d o n C e r t a i n Registers o f I r r e g u l a r M a r r i a g e s Celebrated by U n l i c e n s e d C l e r g y m e n K n o w n as C o u p l e Beggers." 1912-13 XX R o y a l C o m m i s s i o n on D i v o r c e a n d M a t r i m o n i a l Causes, V o l . III. PARLIA House o f C o m m o n s , MENTA R Y DEB A TES The Parliamentary Debates (Official Report), 1911, V o l . 2 1 , 31st J a n . - 2 4 t h Feb., col. 258 ff. House o f L o r d s , The Parliamentary Debates (Official J a n . - 6 t h A p r i l , cols. 1 6 5 - 2 1 1 . Report), 1911, V o l . 7, 31st