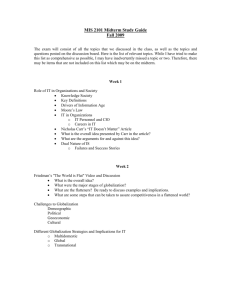

The Globalization of Taxation? Electronic Commerce and the

advertisement