cases outline 659 - E-Book

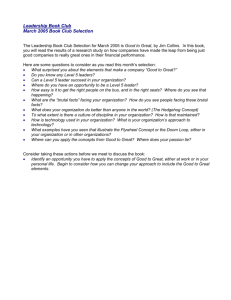

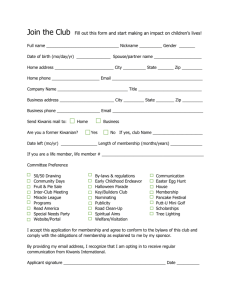

advertisement