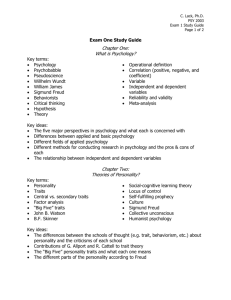

Individual Differences and Differential Psychology

advertisement