NOT FOR COMMERCIAL USE

advertisement

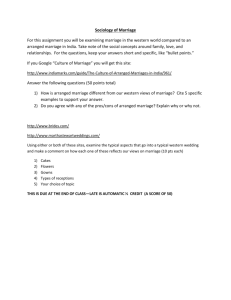

I Articles Involuntary Bachelorhood in Rural China* ER C IA L U Li Zhang Fudan University SE Yan Wei Xi’an University of Finance and Economics R C O M M Despite the universality of marriage in Chinese society, involuntary bachelorhood exists, and is becoming an increasingly critical issue. While many studies have addressed the problem from the standpoint of demographic imbalance, we argue that the issue should be understood as a manifestation of the gendered features of the marriage system which work against low-class men. This understanding relates involuntary bachelorhood to the combined effects of spouse selection and marriage practices. To elaborate our argument, the present study explores nuptiality plights of involuntary bachelors. In particular, it examines their marginalisation in the marriage market, defiant choices in the face of market exclusion, and instability of marital relationships. N O T FO Keywords: Involuntary bachelorhood, the gendered features of the marriage system, sex imbalance, criteria of spouse selection, women’s hypergamy INTRODUCTION A salient characteristic of the Chinese demographic system is an unbalanced marriage market from a gender perspective. From the sixteenth through the late nineteenth century, around 7 per cent of all 40-year-old men were still bachelors and the proportion of spinsters was virtually zero (Lee and Wang 1999). According to the latest national census, by 2010 rates of the never-married had been higher among men (5 per cent) * This research is supported by the National Social Science Foundation of the PRC (13BRK025). CHINA REPORT 51 : 1 (2015): 1–22 Sage Publications Los Angeles/London/New Delhi/Singapore/Washington DC DOI: 10.1177/0009445514557388 2 Yan Wei and Li Zhang N O T FO R C O M M ER C IA L U SE than women (less than 1 per cent) (Population Census Office of the State Council & the National Bureau of Statistics of China 2012). This marked variation in marriage rates by gender implies a marriage squeeze against men. Men who have to delay or forego marriage usually belong to the bottom rungs of the social hierarchy and are often concentrated in the poorer rural regions (Davin 2007; Ye and Lin 1998). Involuntary bachelors, referring to those who become unwanted in the marriage market, suffer a socially undesirable fate in their marital lives. They are well past a culturally defined ‘appropriate age’ for marriage, but fail to marry in the conventional way.1 In a society that treats marriage as an essential institutional setting for the continuation of the patrilineage, non-marriage is both rare and stigmatised. Bachelorhood is regarded as a failure in the man’s life course and receives a low level of social approval.2 Despite facing slim chances, involuntary bachelors are pressured to terminate their single status and make ‘unusual’ attempts to get an offer of marriage. Even so, their efforts often fail to produce desirable outcomes. These nuptiality plights suggest that involuntary bachelorhood is a dynamic process of marriage marginalisation, attached to several distinct attributes like marginalisation in the marriage market, diverse practices of ‘lower’ (or less socially acceptable) forms of marriage in the face of marriage exclusion, and instability of marital relationships. These attributes do not exist in isolation; instead, they interact with and are shaped inexorably by patriarchal culture that defines the gendered features of the marriage system in Chinese society. If involuntary bachelorhood is part of China’s demographic reality, how we understand it is critically important for policy. In previous studies, the intertwined attributes of the nuptiality plight are often treated separately. Most of the attention has been directed towards problems on the ‘supply side’ in men’s search for partners. For instance, some studies heighten the significance of the prevailing sex imbalance on the male marriage squeeze (a situation with fewer marriageable women than men in the population). Some posit that marriage exclusion is a form of poverty and the risk of bachelorhood is greater for men from impoverished families. By contrast, available literature rarely analyses issues such as men’s motivations for marriage, coping strategies and the resulting consequences. The present study conceptualises the entangled relationships between marital obstacles, options and outcomes from the gendered features of the Chinese marriage system. The conceptualisation ties involuntary bachelorhood to a broader matrix of asymmetric gendered roles and relationships in marriage which is rooted in Chinese patriarchal culture. It takes cognisance of the criteria of spouse selection and the prevalence of virilocal marriage that makes the marriage squeeze have its primary effects on males at the bottom of the social hierarchy. To develop our understanding, the article will first highlight 1 The ‘appropriate age’ of marriage is defined variously from one culture to another. A study observes that the minimum or upper limits of age-at-marriage norm tend to be inversely related to the levels of development. This suggests that the normative age of marriage seems to be lower in underdeveloped areas than in developed areas (Billari et al. 2002). 2 A survey conducted in 2009, which covered 264 villages in 28 of China’s 31 provincial-level units, reports that unmarried men aged over 40 have suffered social discrimination, meaning that bachelorhood is recognised as something unacceptable (Jin et al. 2013). China Report 51, 1 (2015): 1–22 Involuntary Bachelorhood in Rural China 3 theoretical propositions framing our empirical analysis. Drawing on statistical data and field information, the article will then analyse the magnitude of the bachelorhood problem, the reasons why some rural men are prone to be marginalised in the marriage market, marital coping strategies and the outcomes associated with their strategies. CONCEPTUALISATION OF INVOLUNTARY BACHELORHOOD N O T FO R C O M M ER C IA L U SE How does involuntary bachelorhood come into existence in any given society? A demographic perspective explains that the sex ratio imbalance produces adverse conditions in the marriage market for the numerically smaller group. The reasoning is straightforward. In a society where men or women are in short supply, members of the group containing a surplus are forced to either marry later or remain single. Voluminous studies have concerned a negative impact of China’s current one-child policy that reinforces the exigencies of culturally induced son preference and generates a significant shortage of brides (for instance, Banister 2003; Bossen 2005; Das Gupta et al. 2010; Ebenstein and Sharygin 2009; Klasen and Wink 2003; Poston and Morrison 2005; Tuljapurkar et al. 1995; Zeng et al. 1993).3 This concern with demographics has simplified the problem of involuntary bachelorhood to a general consideration of sex ratios in the available mate pool. It emphasises the significance of marriage-market equilibrium as measured by demographic balance and propositions the deficit of women as a crucial determinant of marital probability for men. However, the demographic explanation tells us little in a sustained way about how involuntary bachelorhood is affected by the criteria of spouse selection and marriage practices, which are critically related to gender relationships of dominance and subordination in the process of marital formation and sustainability. The gendered features of the marriage system are pertinent to varied socio-economic roles men and women perform upon marriage. In the family, men are assumed to be the main financial providers while women remain at home as home caregivers. In the responsibility for the expenditure on marriage, the financial contribution of the groom should be much larger than that of the bride under the dowry/bride-price system. In post-marital residence arrangements, the married woman is supposed to reside with the husband’s family. In carrying out the duty to ensure the continuation of the ancestral line, men must carry on the family lineage, with women serving as a reproductive tool. These gendered distinctions ‘discriminately’ assign men to play a dominant role compared to women in the family’s well-being and social reproduction within the Chinese patriarchal, patrilineal system. Something important to note about these gender-differentiated roles is that, interacting with other sorts of inequality (such 3 The sex ratio at birth in China has been steadily increasing, climbing from 104.88 boys per 100 girls in 1953 to 118.06 in 2010 (Peng 2011). The abnormal masculine sex ratio at birth (108.47) was first reported in 1982 and had worsened since then. China Report 51, 1 (2015): 1–22 4 Yan Wei and Li Zhang N O T FO R C O M M ER C IA L U SE as class, income and education), they underline the social function of marriage and the criteria of spouse selection in explaining men’s probability of marriage. An asymmetry of gendered roles in marriage and in family reinforces and is reinforced by the social function of marriage which powerfully shapes the practical criteria of spouse selection and marriage pattern. Finding a spouse may be a difficult, if not insurmountable, matter for men who are on the bottom of the social hierarchy. Instrumentally, marriage serves as a segregating and interlinking mechanism for the reproduction of social relations, which may in turn influence the choice of marriage partners. In addition to its functional link to family formation and human reproduction, the marital relationship, in effect, involves transactions of property, status, entitlements and obligations among families, usually in different ways for different classes (Blossfeld and Timm 2003; Gould and Paserman 2003; Watson and Ebrey 1991). This means that the marriage market is segmented by class at each layer of the social hierarchy, creating various marriage pools, instead of one big pool, in association with different layers of the hierarchy. In many cases, economic standing trumps most other considerations in spouse selection.4 Educational attainment and political status also rank highly (Zhang 2013). The criteria of spouse selection have significant negative effects for men when women favour men with better prospects. Men of lower socio-economic status either are unable to get married or have to make socially less desirable marriages. Treating the mate-selection process as similar to the matching of demand and supply in commodity markets, prior research has noted that the problem of involuntary bachelorhood is more structural than numerical in terms of the market availability of potential spouses (Becker 1981; Lichter, McLaughlin et al. 1992; Lichter, Qian et al. 2006; Qian 1998; Qian and Preston 1993). That said, involuntary bachelorhood (or a male marriage squeeze) is essentially spurred by the structurally unfavourable marriage market that low-class men face. Involuntary bachelorhood is compounded by marriage patterns which conform to the patrilineal power structure where men outrank women in many respects.5 In stratified societies where males have more power and control a greater share of wealth, the popularity of hypergamy (the need/desire to marry up socio-economically) among women can be seen as an instance of women using marriage as a leverage to negotiate for social equalities. Given their generally subordinate status under the Chinese patriarchal, patrilineal system, women tend to compete for resources and upward mobility through marriage or inter-regional marriage migration. Social as well as spatial hypergamy has a strong effect on the scanty marital opportunities for impoverished men. As women move out and up, a shortage is created at the bottom layer of the hierarchy in certain localities. Earlier studies document that marriage is often taken by low-class women as 4 According to a national survey, what most people have meant by economic standing has been economic variables such as cash income and the wherewithal to make marriage payments (National Survey Research Center at Renmin University of China 2009). 5 For example, daughters are socially constructed less valuable than sons due to their gender, and are regarded as a burden on the family. China Report 51, 1 (2015): 1–22 Involuntary Bachelorhood in Rural China 5 M ER C IA L U SE a means to trade or compete for wealth and status among various layers of the society. Thus, the collapse of marital prospects for men usually occurs in poor areas of the country, since many women migrate from poor areas in the countryside to wealthier urban areas in pursuit of men of higher status (Bossen 2007; Coontz 2005; Ebenstein and Sharygin 2009; Fan and Huang 1998; Kaur 2012; Oppenheimer 2000). When there are strong cultural and economic imperatives for men to marry,6 bachelors with inferior socio-economic characteristics must employ diverse strategies to cope with the unfavourable marriage market and a shortage of women who can be seen as potential matches. In addition to relatively obvious responses such as lowering spousal preference, bride purchase is one reaction. Brides are bought or abducted from a long distance away, or even across national borders.7 Another rational reaction through which men with few assets attempt to escape bachelorhood is to opt for marital arrangements that would not be a drain on their family resources (for example exchange marriage or wife-sharing), though such arrangements may not necessarily have positive outcomes, or may even constrain their long-term socio-economic prospects. As we will discuss later, involuntary bachelors engage in marital practices (for example, marriage by purchase, uxorilocal marriage, levirate, widow remarriage) that are considerably abnormal in contrast to conventional marriage in order to fulfil their marriage hopes.8 M METHODOLOGY N O T FO R C O Information from a single source is hardly able to capture the specifics of involuntary bachelorhood. For analytical purposes, we draw together three sets of data/information (censuses and national surveys, press reports and interviews), which are complementary in that they allow us to establish connections between broad and narrow scales. We use census age-specific marriage data to estimate the magnitude of the nationwide population of rural involuntary bachelors. We also use the data from the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS) to investigate how marriage patterns can affect the man’s marriage prospects.9 These macro data allow us to get a handle on the context of broad socio-economic structures that shape personal experience. 6 The all-marriage tradition is said to be institutionally linked to partilineal ideology characterised by a strong son preference. It can also be seen as an outcome of economic necessity in agrarian societies that require both male and female labour to ensure the family’s viability (Kaur 2008). The authors would like to thank a reviewer for raising this important justification for universal marriage. 7 Anonymous sources reported that in China about 20,000 women were abducted and sold into marriage every year. Trafficking accounted for 30–90 per cent of marriages in some villages. See US Department of State (2006). Additionally, see Chu (2011) and Zhao (2003). 8 Though not found in our field study, some cases of polyandrous arrangement are reported in the media, in which the wife of one man is shared by several others. 9 The CGSS is an annual questionnaire survey of China’s households aiming to investigate systematically the changing relationship between social structure and quality of people’s life. More information is available on its official website, http://www.chinagss.org. China Report 51, 1 (2015): 1–22 6 Yan Wei and Li Zhang Involuntary bachelors are common throughout vast areas of rural China. Regrettably, quantifiable countrywide data on their personal characteristics are unavailable. Instead, we construct the profile of involuntary bachelors by compiling scattered press reports. This is done through reading about 1300 cases reported in the past 10 years. These cases cover 16 villages of 12 cities in 11 provinces. Although cases gathered from media sources may not be statistically representative, they are instrumental in providing stereotypes of involuntary bachelorhood (Table 1). Table 1 Summary of Stereotypes Associated with the Nuptiality Plight of Involuntary Bachelors in Rural China Characteristic Individual Age: Ages span from men in their late twenties to their seventies, with the bulk of the sample between 30 and 45 years old. U Background characteristics at the various levels SE Attribute IA L Educational attainment: The vast majority of cases report an elementary education or less. ER C Source of income: Most have agriculture plus short-term off-farm jobs. M Skills for daily living: Capable in menial, labour-intensive jobs only. O M Personality: Low level of self-esteem, weak socialisation with few social ties to the communities they are attached to. Family structure: Primarily large-sized families with multiple adult children. N O T FO R C Family Work capacity: At least one adult family member without work capacity. Living arrangement: Co-residence in the parental home with unmarried siblings. Housing condition: Dilapidated and shabby structure awaiting reconstruction. Family well-being: Prevalence of extreme poverty surviving on less than a specific level of income (the poverty line) per day. Village Geography: Mountainous terrain featured by karst landforms inaccessible to motor vehicles. Resource: Scarcity of farmland and water. Economic structure: Domination of low value-added rudimentary agriculture; disconnection of the villagers’ livelihood to the market as a result of lacking cash crop farming and household side business. Income level: A per capita annual income of 200–2000 yuan, putting them in the lowest level of the national rural areas. (Table 1 Continued) China Report 51, 1 (2015): 1–22 Involuntary Bachelorhood in Rural China 7 (Table 1 Continued) Attribute Characteristic Causation of involuntary bachelorhood Poverty as the prominent factor constraining available choices. Martial strategy Increase of family income to attract potential wives. Expansion of the pool of potential brides by lowering the criteria in choosing wives. Illegal or abominable forms of marriage, such as wife purchase. Marital outcome Continuation of involuntary bachelorhood despite many attempts to find a wife. High risk for being victimised by marriage scams. SE Devoice shortly after marriage as wives refuse to endure perpetual economic hardship. IA L U High pressure driven by responsibility for taking care of elderly and disabled members in the conjugal family. C Source:Compiled from press reports. N O T FO R C O M M ER Our analysis is also based on the examination of qualitative information from interviews, which allow investigation of poignant personal experiences with a considerable degree of qualitative analytical depth. The interviews were conducted during several visits to three villages (labelled X, Y and Z as pseudonyms) in two townships in western China from 2010 to 2012. Though not representative of all of rural China, these villages resembled other poor villages of the countryside. Our fieldwork sites shared similar features in terms of geographic setting, demographic profile, economic structure and living standards, and were regarded as the areas worst affected by problems of involuntary bachelorhood in press reports. They were scattered in a mountain belt (from 500 m to 1900 m above sea level), accessible only by mud tracks. Each village had about 250 households and 1100 residents. Farming there was labour intensive but not very productive. Labour migration was the most important channel of cash income. Poor accessibility and unprofitable agriculture resulted in per capita income in these mountainous villages far below the national average.10 Interviews were carried out with a total of 16 individuals. All of the interviewees had a hard time trying to fulfil their marriage hopes. We reached them with assistance from village cadres, and included only those who were willing to be interviewed. Not unexpectedly, interviewees shared unfavourable personal traits described in Table 1, rendering them among the least desirable participants in the marriage market. Interviews were conducted individually in a semi-structured, open-ended manner, covering questions about family background, barriers and approaches to seeking 10 Current per capita annual incomes were about 3000 yuan, 1600 yuan and 1400 yuan in villages X, Y and Z, respectively. Data were derived from village leaders. China Report 51, 1 (2015): 1–22 8 Yan Wei and Li Zhang marriage partners, marital forms, post-marital residence arrangements and relations. In the following section, we report this written and ethnographic evidence. EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE N O T FO R C O M M ER C IA L U SE Figure 1 provides estimates of the percentage of single persons of each age group who would remain single, based on the national nuptiality tables constructed by the authors.11 These statistics, disaggregated along gender lines, indicate the marriage trend and the magnitude of the bachelor population. Though there has been a small rise in non-marriage rates by age over time,12 Chinese society is still characterised by nearuniversal marriage. Most Chinese end their single status between the ages of 20 and 35 years. People over the age of 35 may be considered as having difficulties realising their marital aspirations. The proportion of men who never married was apparently higher than the proportion of women in a similar position. While nearly all women married at some time in their lives, 5 per cent of men never married. The rural–urban difference in the size of the bachelor population was also striking. According to the latest census, by 2010, the number of never-married males was 4.2 million in rural areas, while the bachelorhood rate was 1.5 per cent. In cities, the same statistics were 1 million and 0.4 per cent respectively (Population Census Office of the State Council & the National Bureau of Statistics of China 2012). Given the supposed universality of marriage, such a large bachelor population should be viewed as the ineluctable outcome of structural forces, rather than the result of preferred choices on the part of bachelors. Men’s opportunities to marry are affected by women’s hypergamy. Using educational attainment as a close proxy for economic standing and social status, Table 2 demonstrates that most Chinese women have tended not to marry down socio-economically. Figures in the diagonal cells of this cross-classification of wives and husbands’ educational attainment showed marriages characterised by educational homogamy, whereas off-diagonal cells revealed those characterised by educational hypergamy or hypogamy. While many marriages occurred across educational categories, women seldom marry down the education hierarchy. In contrast, men tended to be much less likely to marry women receiving more education. That is to say, there was little prospect of finding brides for less-educated males.13 For a technical explanation on the construction of the nuptiality table, see Shryock et al. (1976). Technically, changes in the timing of marriage (for example, an increase in the age of first marriage) can in part produce a rise of the proportion of unmarried persons at each age. 13 Census data show that those better-educated males were less likely to remain permanently single (Population Census Office of the State Council & the National Bureau of Statistics of China 2012). As Telford (1992) notes, in China whether men (unlike women) find a spouse has been primarily conditioned by their social status. Also see Attané et al. (2013). 11 12 China Report 51, 1 (2015): 1–22 Involuntary Bachelorhood in Rural China 9 Figure 1 The Percentage of Single Persons who Remain Single at each Age, by Sex, 1982–2010 90 1982 1990 80 2000 2010 70 60 50 40 30 SE 20 M M 80 49 47 45 43 39 1990 2000 2010 C 60 R 50 FO 40 49 47 45 41 39 37 35 33 31 29 27 25 23 21 19 15 N O T 30 0 1982 O 70 17 Percentage of Single Survivors 90 10 37 ER 100 20 Age C Female IA L 35 33 31 29 27 25 23 21 19 17 15 0 41 U 10 43 Percentage of Single Survivors 100 Age Male Source:Estimated based on the census data of marriage and mortality provided by the National Bureaus of Statistics of China. Table 1 shows that rural involuntary bachelors have certain personal inadequacies in common: low earning capacity, low levels of education, poor sociability and unfavourable family backgrounds, making them unattractive to women. Men who come from the poorest families of the poorest villages usually have the lowest chance of marriage. Educational attainment and family burdens act as other barriers to the China Report 51, 1 (2015): 1–22 11.7 19.7 31.6 33.5 49.1 14.9 M M 10.7 20.9 17.1 C ER 31.6 8.9 1.6 Senior Secondary School 14.7 SE U 17.7 25.6 IA L 10.2 3.9 0.7 Vocational Senior Secondary School Educational Attainment of Wife O C Junior Secondary School R Table 2 Spousal Matches in Educational Attainment (%) FO Source:National Survey Research Center at Renmin University of China (2009). 2.0 17.0 Vocational senior secondary school Bachelor degree or above 19.0 Senior secondary school 8.0 36.9 Junior secondary school Some college 82.7 Primary School or Below Primary school or below Educational Attainment of Husband T O N 25.1 26.7 7.5 4.8 1.0 0.0 Some College 35.8 7.0 1.3 0.9 0.2 0.1 Bachelor Degree or Above 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 Total 307 498 719 1,321 3,352 2,503 No. of Samples (N) Involuntary Bachelorhood in Rural China 11 likelihood of marrying. Two interview extracts from our fieldwork sample justify these observations. FO R C O M M ER C IA L U SE A 43-year-old man (Mr C) with elementary education was the last of four siblings.14 His eldest brother had been missing for years. His second brother worked far from the hometown and seldom visited home. His sister married virilocally in another village. C lived with his 80-year-old father and third, unmarried brother, who had suffered from dementia since childhood. The main source of C’s family livelihood was seasonal crops on a small plot of infertile land. Renting out his two cattle to others for farming during seeding/planting seasons provided a small, unstable subsidiary income. As a case of extreme hardship, the family received a 100 yuan monthly living allowance from the government. Because the two family members he lived with were incapable of looking after themselves, C could not work outside of the village for cash income. C had tried dating several times without success, because few women were willing to be trapped in poverty after marriage. He had long drifted between hope and despair for marriage. Mr D was now in his late thirties. D’s 66-year-old father suffered from a chronic disease and his mother was disabled. Both needed a certain amount of regular expenses on medical care. A small plot of contracted farmland provided the family with food. D was employed in drilling highway tunnels, with a monthly income of around 3000 yuan. Nonetheless, D had to spend most of the income on his parents’ medication and on hiring someone to farm the family’s land, since neither of his parents could undertake labour-intensive farming. With high family expenditures, D was unable to save sufficient money to build a matrimonial house, which cost at least 30,000 yuan in his village. D had had two dating experiences, but both cases ended in failure. His marital dream had been crippled by his heavy family burden. After years of failure, D no longer expected that he could secure a marriage. N O T Figure 2 illustrates individual vignettes selected from our informants, that can exemplify how involuntary bachelors struggle for marriage, and the problems associated with their marital life. A 40-year-old (Mr E) with 3 years of schooling lived in Village Z, which was full of frustrated bachelors because of extreme poverty (Figure 2(a)). Girls of the village often had their pick of potential husbands in richer areas. For E, getting a wife from the local community proved nearly impossible. After he managed to accumulate enough cash, he and two villagers, arranged by a marriage broker, travelled thousands of kilometres to a border province to purchase brides. Each bride cost about 30,000 yuan. Mr. E locked up his bought wife to keep her from escaping. Rather than condemning this action, villagers applaud this case of ‘buying a bride’ as a palatable option for involuntary bachelors. They sided with those men who 14 Pseudonyms are used to keep the anonymity of our informants. China Report 51, 1 (2015): 1–22 12 Yan Wei and Li Zhang Figure 2 Martial Forms and Residence Arrangements by Involuntary Bachelors, Selected Cases E Marriage by purchase (a) SE Uxorilocal marriage G M ER C IA L U (b) C O M (c) Virilocal marriage O T FO R H Uxorilocal marriage Marriage by purchase (d) N J Levirate marriage Lenged Male Marital relationship Female End of marital relationship A co-resident with interviwee Person already died Kinship Number of children not shown Source: Drawn by the authors based on the information from interviews. China Report 51, 1 (2015): 1–22 Involuntary Bachelorhood in Rural China 13 N O T FO R C O M M ER C IA L U SE parted with their life-time savings to buy wives and kept a tight watch over their purchased brides. Not long after being purchased, the woman took the chance to run away with two brides who were also sold into marriage on the same occasion. Fearing the possibility of another loss of both wife and money, E did not intend to buy a wife again and remained unwed at the time of interview. Mr G, from a neighbouring township, married uxorilocally with a woman from an economically better-off family in Village X when he was over the age of 30 (Figure 2(b)).15 G came from an impoverished family with five brothers while the woman had two sisters reaching marriageable age. The couple had one son and one daughter. The daughter inherited G’s surname but the couple’s son was given his mother’s surname. This effectively ended the transmission of G’s family name. With financial support from his father-in-law, G bought a 30-seat coach and began operating a short-distance passenger transport business. Having benefited from his marriage, G became affluent by local standards. Mr H from Village Y could not get married till his late thirties (Figure 2(c)). Finding no prospects of getting a local wife because of his less-desirable personal traits, he paid 30,000 yuan to marry a girl from another province, who was in fact a member of a marriage scam gang. The girl fled just a week after the wedding ceremony. Making several attempts to get a wife without success, he finally married one of his female cousins. The woman’s ex-husband had been killed during a mining accident, leaving her with two young children. One year after the death of her ex-husband, the impoverished widow married H uxorilocally. H resided with the widow’s ex-father-in-law after marriage. H’s marriage was a case of exchange marriage between brothers. The woman’s father was a younger brother of H’s grandmother, and H was a cousin of the woman’s ex-husband. H’s wife was not able to bear children after her new marriage. It was not unusual in Village Y that involuntary bachelors chose to marry widows. Mr J remained single because his parents could not afford to build him a matrimonial house (Figure 2(d)). As requested by J’s parents in his early forties, J was married to the wife of his third elder brother, who had died in a mining accident leaving two young daughters. The family of the deceased man received 6,000 yuan cash in compensation. J’s parents demanded such levirate marriage (a type of exchange marriage among family members) in order to satisfy two material concerns. First, it avoided expensive cost for J’s marriage, since J’s parents had already paid the bride-price for the wife of their deceased son and the woman 15 Uxorilocal marriage, where a man marries into his wife’s family, follows three cultural rules. First, at least one of the children, or all children, born from the marriage has to adopt the mother’s surname. Second, the groom is required to reside with the bride’s natal family. Third, an uxorilocally married man holds the responsibility for taking care of the wife’s parents and is entitled to inherit the property of the wife’s family. Because a called-in son-in-law has lower social status under the patrilineal family system, uxorilocal marriage is still relatively rare in rural China, representing only about 5 to 8 per cent of marriages (Jin et al. 2006). China Report 51, 1 (2015): 1–22 14 Yan Wei and Li Zhang was considered to be the property of the family that had ‘bought’ her. Second, it eliminated any possibility of the transfer of the compensation payment for J’s deceased brother to other families through a new marriage by the widow. This case was not extraordinary.16 DISCUSSION U SE Cross-reading of the written and ethnographic evidence presented in the previous section helps to understand the various interrelated aspects of involuntary bachelorhood: the magnitude of the problem, contributing factors, marital strategies, motivations and subsequent outcomes. IA L The Magnitude of the Problem of Involuntary Bachelors FO R C O M M ER C Notwithstanding the goal of universal marriage, there are a considerable number of men who have never married. Chinese unmarried men are overwhelmingly poor, illiterate and rural. Nationwide, currently about four million rural men remain frustrated in their aspirations to marry, despite the fact that they make efforts to find a spouse. While bachelorhood is socially acceptable in some countries, in Chinese society marriage has long been viewed as a mandatory part of every individual’s life course. In this context, bachelorhood should be perceived as a forced way of life brought on by the vicissitudes of the socio-economic system at both personal and broader levels, rather than a preferred choice. T Factors Contributing to Involuntary Bachelorhood N O China’s rapid industrialisation and increasing labour mobility are reshuffling the country’s social and spatial hierarchy. Both social and regional disparities are on the rise.17 Widening gaps in development have intensified competition for brides, and put impoverished local individuals at a disadvantage. Cases from our fieldwork show that involuntary bachelors face lives of economic destitution and are the weakest competitors 16 We came across five other levirate marriages on several occasions during our visits to those villages. In J’s village, the levirate marriage custom, which was a forced marriage of a widow to the brother of her deceased husband, was conceived as both rational and beneficial. The remarried widows were not treated any differently from other brides within the villages. 17 For example, consider the following rural–urban gaps. With respect to about 65 per cent of villages and 46 per cent of rural population, the annual net income per capita was less than 21 per cent of urban disposable income. For about 31 per cent of rural families, their annual income was less than the national average (National Survey Research Center at Renmin University of China 2009). China Report 51, 1 (2015): 1–22 Involuntary Bachelorhood in Rural China 15 N O T FO R C O M M ER C IA L U SE in the marriage market. Multidimensional factors contribute to the chronic poverty of the villages and the involuntary bachelors themselves. Topographic features make land and water resources there extremely scarce, causing challenges in developing commercial farming. With subsistence depending on a fragile ecosystem, the only viable resource is cheap and less-educated labour. Poor transportation and an adverse living environment ensure that these villages are isolated from resource inflows (capital and technology) and are generally beyond the effective reach of government anti-poverty programmes. Geographic isolation and exclusion contribute to the persistence of poverty, which in turn translates directly into diminished prospects for the marriage of impoverished men. Income inequality and poverty are themselves unequally distributed throughout the country and across social categories. As can be expected, men disadvantaged in the marriage market are in the lowest class. For involuntary bachelors who belong to groups of the poorest residents in poverty-stricken villages, poverty is not only a village-level but also a family-level phenomenon. Though most involuntary bachelors are able to work, they come from impoverished families with several members who suffer either physical disabilities or chronic diseases. Because of the need to care for their elderly or disabled family members, involuntary bachelors cannot take opportunities to migrate for higher incomes. Involuntary bachelors also come from poor families with multiple sons that cannot finance marriage for all sons. The family factors, such as high dependency ratio, low labour-earning capacity and a shortage of off-farm sources of livelihood, are among the factors that keep involuntary bachelors in a serious predicament, both in their search for marriage and in their very survival. Traditional conventions regarding gender roles in marriage and in family remain very much alive in these poor villages. Villagers are accustomed to the practice deriving from the patrilineal family institution that upon marriage a woman should fully belong to her husband’s family (virilocal marriage). They believe that the groom should pay the most for the marriage. Any marriage organised outside such a financial arrangement is regarded as ‘deviant’ or ‘inferior’. In considering marrying, women expect that the economic situation of the groom’s family should be better than their own. Population registration data in these villages do not show a serious imbalance in male–female demographics.18 However, many women have married outside their villages when facing the prospect of not finding local qualified grooms. Involuntary bachelorhood occurs as not only an outgrowth of poverty at multiple levels (individual, family and village) but also as a result of the propagation of trans-local female hypergamy, the marriage pattern responding to the reality of men’s superiority to women under patriarchy. When hypergamy represents one of the few mechanisms by which lowstatus women can achieve social mobility, these poorest villages experience a net loss of marriageable women, and men face a socio-economically as well as geographically structured marriage squeeze. 18 The ratios of male to female ranged between 103/100 and 108/100 in the past 20 years. China Report 51, 1 (2015): 1–22 16 Yan Wei and Li Zhang IA L U SE Our findings help enrich previous accounts of causal factors underlying involuntary bachelorhood. Unlike studies which pay most attention to the significance of a sex ratio favouring males that generates the shortage of brides, this study addresses the need to incorporate issues of spouse selection and marriage patterns alongside demographic explanations of the male marriage squeeze.19 Without denying the plausible constraints imposed by the growing gender disequilibrium on the future of marriage in China, we postulate that those in the most disadvantaged position of the socioeconomic hierarchy fail to marry largely in the context of a specific marriage system. Involuntary bachelorhood is shaped not so much by a quantitative shortage of marriageable women as by the males’ qualifications as husbands, and by the tendencies towards female hypergamy in the context of women’s subordination to men. Seen in this light, involuntary bachelorhood is better understood through gendered, institutional constraints on marriage. These constraints cannot be easily overcome through the state’s current efforts to alter demographic imbalance.20 C Marriage Strategies, Motivations and Subsequent Outcomes N O T FO R C O M M ER Our case studies suggest that for men in disadvantaged positions in the marriage market, marriage is both a necessity and a predicament. Impoverished bachelors do not prepare for lifelong bachelorhood. Their search for potential wives may go on for years and extend for thousands of kilometres. Given the dismal marriage market for them, involuntary bachelors also adopt several alternatives to conventional virilocal marriage, enhancing their chances of de facto, if not officially recognised, marriage. Those with small savings buy women to serve as wives that are not legally recognised. Uxorilocal marriage, in which after marriage a husband resides with his wife’s parents who have no sons, is another option. Those who cannot make enough from barren farmland to buy a wife also wed women who otherwise have little chance of marrying (such as those with physical or mental disabilities), or enter into forms of marriage bearing socially negative meaning (such as marriage with members from the same clan-family or levirate marriage). These defiant alternatives can be taken as an indication that involuntary bachelors attempt to expand the definition of marriageable women by moving away from the cultural straitjacket that privileges patriarchal marital forms.21 Such alternatives, which provide impoverished men with wives, are 19 Available data show that, from 1953 to 2010, the proportion of bachelors in the population was quite stable (at around 4–5 per cent), regardless of a tendency of increase in the level of sex ratio at birth (from 105 boys per 100 girls to 118) in the corresponding period (Lu and Zhai 2009; Peng 2011; UNFPA 2007). 20 In recent years, the Chinese government has intensified its efforts against sex selection of offspring. The measures include prohibition of illegal prenatal sex determination, sex-selective abortion and female infanticide. The government has also launched several initiatives to raise the status of daughters, such as a nationwide ‘girl care’ project. 21 See McGough (1981) for more marital forms that deviate from the conventional standards for marriage. China Report 51, 1 (2015): 1–22 Involuntary Bachelorhood in Rural China 17 N O T FO R C O M M ER C IA L U SE tolerable in local societies, because the ‘defiant’ marriages of marginalised individuals can hardly generate any impact on the existing marriage norms, which are normally sustained by a long-lasting male-dominated system. The alternative marital forms (shown in Figure 2) undertaken by involuntary bachelors break sharply with the tradition of virilocal marriage, but serve as a costminimising way to alter marriage chances in a marriage market that is highly unfavourable for poor men. Impoverished bachelors usually cannot enter into virilocal marriages, although they are the most common form of marriage in rural China by far. Virilocal marriage involves different arrangements concerning the responsibility for ritualised marital expenses, and requires the groom’s family to pay for the majority of these expenses. This arrangement is perceived as compensation to a bride’s family for rearing the daughter (Zhang and Chan 1999). In the villages we visited, by custom, the major items of conspicuous expenditure for a given virilocal marriage include a furnished matrimonial house, betrothal money, trousseau, wedding ceremony and payment for marriage-related ritual obligations (referring to the money and goods given by the newly-wed couple to the bride’s parents shortly after the marriage).22 For the poor, the costs of those mandatory items can be converted into a large lump sum, which amounts to many years of their family income and in many cases plunges them deep into debt. Alternative forms of marriage cut down on the number of expenditures incurred in a marriage, and therefore reduce the customary marital expenses substantially. In the case of uxorilocal marriage, the bride’s family is usually responsible for most of the marriage expenses. In the case of ‘bride purchase’, the groom makes a one-time payment only, and commits to no financial relationship with the bride’s natal family afterwards, making the post-marital ritualised exchange of cash or trousseau to the bride’s family unnecessary. In the case of levirate marriage, the groom’s family ‘recycles’ a woman who has married into the groom’s family, avoiding any loss of the groom’s household wealth. Usually re-married women gain nothing from re-marriage. For impoverished men, these ‘irrational’ marriage options minimise marital costs, which are traded for the low prestige of these ‘deviant’ marriage forms. These forms of ‘irrational’ marriage, usually considered as a marginal practice, are actually the most accepted form of marriage for the rural poor. Unusual marriages shed light on the motivations behind marriage. Contrary to what the social convention assumes, our cases show that the continuation of the patrilineage is more a perceived cause than a real motivation to form a conjugal unit. Traditionally, marriage has been cast as a basic bulwark for a patrilineal society that values the importance of offspring for both family survival and prosperity, and stresses the necessity of having at least one son. Chinese Confucian ethics condemns life without sons, stating that ‘being sonless is the most unfilial behavior in one’s life’. Marriage, as the only socially acceptable route to reproduction, is expected to play a decisive role in 22 Bride prices are rising quickly in China, reflecting an obsession with materialism during a period when Chinese society has been increasingly commercialised (China Daily 2013). China Report 51, 1 (2015): 1–22 18 Yan Wei and Li Zhang N O T FO R C O M M ER C IA L U SE the perpetuation of the patrilineage.23 While marriage supposedly links to biological reproduction of the patrilineage and the possibility of continuing the family line, the marriages of our informants do not secure male heirs. They either marry uxorilocally in which case the man’s family name is not always transferred to his male offspring, or marry with women who cannot bear children that would perpetuate the male line. Even though involuntary bachelors may have wished to have their own sons, they have to give up the possibility of doing so in order to secure an offer of marriage. The overwhelming concern of our informants regarding the marital choices is to obtain a spouse at an affordable cost, rather than to reproduce their patriline. A high level of social disapproval for bachelorhood seems to be a primary reason for the marriage imperative in poor rural communities. Involuntary bachelorhood can be a profound source of pain for many adult men and their families. Those who have failed in accomplishing marriage are looked down upon in the villages. Narratives from our informants show that involuntary bachelors are not regarded as socially ‘full’ persons and are often stigmatised as social outcasts. They experience problems ranging from feelings of shame to lack of social recognition. In fact, the social discrimination that involuntary bachelors suffer and the motivation to escape the bachelorhood are intricately interwoven. At the family level, the single status of the adult sons causes the parents tremendous psychological stress and deep remorse. To avoid the possibility of unfavourable social pressure, parents tend to identify their sons’ marriage as one of their most fundamental duties. Parents give top priority to their sons’ need to be married, and try their best to satisfy it. This, in turn, may reduce the emotional burden on the family. Life after marriage differs depending on the different types of marriage. Of the various marital forms, uxorilocal marriages with previously unmarried women often result in slightly better socio-economic outcomes (Figure 2(b)). In these cases the brides’ families usually have better economic standing and more material resources that can be channelled into the marital relationship. By contrast, other marital forms (including uxorilocal marriage with previously married women, as shown in Figure 2(c), are often associated with desperation. In these cases, the equally poor bride’s family provides the groom with neither economic means nor opportunity to improve his socio-economic marginality. ‘Bride purchase marriages’, a kind of coerced marriage, are relatively cheap but fragile. Those who buy women to serve as wives often suffer marriage fraud, and are at greater risk of marital disruption than those who pursue other marital choices. Marital disruption can cripple the families that use up their resources to buy a wife. The only generalisations that can be made about the various strategies of marriage adopted by involuntary bachelors is that socio-economic outcomes of marital relations seem to be complex and unpredictable, rendering risks faced by those who might manage to get a wife unclear. Simply getting married does not necessarily offset the long-term deleterious effects of socio-economic marginalisation on marriage. 23 Jones and Gubhaju’s study (2009) indicates that, in China, marriage and parenthood are tightly linked and sequenced. Few births are found outside marriage. China Report 51, 1 (2015): 1–22 Involuntary Bachelorhood in Rural China 19 CONCLUDING REMARKS N O T FO R C O M M ER C IA L U SE The present study views involuntary bachelorhood as a manifestation of the gendered features of the marriage system which discriminate against low-class men. This standpoint acknowledges the strength of cultural norms governing marriage and elucidates the phenomenon of involuntary bachelorhood in to the light of the combined effects of spouse selection and marriage practices. It conceives marriage exclusion among those who share a derogatory Chinese term—‘bare sticks’ (referring to men who do not have families of their own)—with an etiology of gendered roles upon marriage. In other societies, nuptial choices and resulting outcomes are intimately connected to class-based inequalities within constricting social structures, such as caste hierarchy in South Asia and class structures in Europe (Duby 1978; Hughes 1978; östör et al. 1982; Parry 1979). In the Chinese case, a marriage squeeze against ‘surplus’ men who are unwanted in the marriage market is socially embedded. It is underpinned by a gendered role structure within marriage relationships and in the family. ‘Abnormal’ marital choices made by this population, who have much less control over spouse selection, are in fact ‘rational’ strategies which compensate for their vulnerability on the marriage market. For the majority of involuntary bachelors, marriage and life after marriage can be a painful and marginalising process. Socio-economic repercussions of involuntary bachelorhood at the national level are far from clear. Nonetheless, the subject merits some attention. In addition to the plights of individuals, scholars are concerned with social suffering on a broader scale. Even though the current demographic imbalance will produce no salient effect on the Chinese marriage market until 10 or 20 years later,24 some speculate that the prevalence and persistence of involuntary bachelorhood may constitute a ‘social time-bomb’ that endangers public security and social stability (Edlund et al. 2009; Hudson and Den Boer 2002, 2004; Yang et al. 2009). Other substantive implications are also possible but may not be straightforward.25 What we can be sure of is that involuntary bachelors have to bear the brunt of suffering resulting from their failure on the marriage market. We can also anticipate that the nuptiality plight of this segment of the population suggests that they will have to face great uncertainties in planning their life course events (such as family formation, fatherhood and conjugal relationship). Their responses to 24 The statistical significance of involuntary bachelorhood remains to be established. Attané (2006) estimates that the sex ratio among people aged 15–49 will reach around 117–120 men per 100 women in 2050. Tucker and Hook (2013) project that the number of single men (aged 25–39) will reach a peak at almost 30 million in 2030. 25 For example, Wang and Mason’s (2005) study argue that the economic benefits of a surplus of adult single men may include fewer dependents and more time spent on working. Tucker et al. (2005) speculate that the population of involuntary bachelors could serve as a new transmission path of HIV/AIDS from high-risk to low-risk populations. Attané et al. (2013) write on the illegal sexual behaviour of involuntary bachelors. Lee and Wang’s study (1999) points out that, in many regions of China, up to as many as 16 per cent of all 40-year-old men had not married. For this reason, one may argue that the future surplus of marriageable young men may not be a serious problem in historical terms. China Report 51, 1 (2015): 1–22 20 Yan Wei and Li Zhang ER C IA L U SE the consequences of marital constraints and how the strategies subsequently affect broader social changes will be important topics from a policy standpoint. China’s patriarchal culture values males and devalues females in many respects. Nonetheless, as we have seen, involuntary bachelors do not invariably benefit from a setting of men’s superiority to women in terms of marriage. Many of them remain unmarried or have to marry in unconventional ways. In the policy arena, rural involuntary bachelors are often excluded from disadvantaged social categories entitled to state support. In past decades the Chinese government has launched a large collection of policies devoted to alleviating the problems of gender inequality and female subordination. Programs are offered that treat females as victims of patriarchal culture who are in need of more state protection and care. While the Chinese patriarchal system is being officially undermined, so far few government measures and resources are geared to helping involuntary bachelors resolve their marriage problems that may originate from several gendered features of the Chinese system of marriage. If the presence of large numbers of involuntary bachelors can threaten the national socio-political order in many ways, how to manage their marriage dilemma will be a matter of concern for China’s development. M References N O T FO R C O M Attané, Isabelle, Zhang Qunlin, Li Shuzhuo, Yang Xueyan and Christophe Z. Guilmoto. 2013. ‘Bachelorhood and Sexuality in a Context of Female Shortage: Evidence from a Survey in Rural Anhui, China’, China Quarterly, No. 215, 703–26. ———. 2006. ‘The Demographic Impact of a Female Deficit in China, 2000–2050’, Population and Development Review, Vol. 32, No. 4, 755–70. Banister, Judith. 2003. ‘Shortage of Girls in China Today’, Journal of Population Research, Vol. 21, No. 1, 19–45. Becker, Gary. 1981. A Treatise on the Family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Billari, Francesco C., Alexia Prskawetz and Johannes Fürnkranz. 2002. The Cultural Evolution of Age-atMarriage Norms. Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research Working Paper (WP 2002–018). Blossfeld, Hans-Peter and Andreas Timm (eds). 2003. Who Marries Whom? Educational System as Marriage Markets in Modern Society. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers. Bossen, Laurel. 2005. ‘Forty Million Missing Girls: Land, Population Controls and Sex Imbalance in Rural China’, Japan Focus, 7 October. ———. 2007. ‘Village to Distant Village: The Opportunities and Risks of Long-distance Marriage Migration in Rural China’, Journal of Contemporary China, Vol. 16, No. 50, 97–116. China Daily. 2013. ‘Brides Become Expensive in China’, 5 June, http://usa.chinadaily.com.cn/china/201306/05/content_16570397.htm (accessed on 22 June 2013). Chu, Cindy Yik-Yi. 2011. ‘Human Trafficking and Smuggling in China’, Journal of Contemporary China, Vol. 20, No. 68, 39–52. Coontz, Stephanie. 2005. Marriage, A History: From Obedience to Intimacy, or How Love Conquered Marriage. New York: Viking Penguin. Das Gupta, Monica, Avraham Ebenstein and Ethan Jennings Sharygin. 2010. China’s Marriage Market and Upcoming Challenges for Elderly Men. The World Bank Policy Research Working Paper WPS5351. Davin, Delia. 2007. ‘Marriage Migration in China and East Asia’, Journal of Contemporary China, Vol. 16, No. 50, 83–95. China Report 51, 1 (2015): 1–22 Involuntary Bachelorhood in Rural China 21 N O T FO R C O M M ER C IA L U SE Duby, Georges. 1978. Medieval Marriage: Two Models from Twelfth-century France, Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press. Ebenstein, Avraham and Ethan Jennings Sharygin. 2009. ‘The Consequences of the “Missing Girls” of China’, The World Bank Economic Review, Vol. 23, No. 3, 399–425. Edlund, Lena, Hongbin Li, Junjian Yi and Junsen Zhang. 2009. Sex Ratios and Crime: Evidence from China, Columbia University Department of Economics Working Paper (Version 6 February). Fan, Cindy C. and Youqin Huang. 1998. ‘Waves of Rural Brides: Female Marriage Migration in China’, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, Vol. 88, No. 2, 227–51. Gould, Eric D. and M. Daniele Paserman. 2003. ‘Waiting for Mr. Right: Rising Inequality and Declining Marriage Rates’, Journal of Urban Economics, Vol. 53, No. 2, 257–81. Hudson, Valerie M. and Andrea Den Boer. 2002. ‘A Surplus of Men, a Deficit of Peace: Security and Sex Ratios in Asia’s Largest States’, International Security, Vol. 26, No.4, 5–38. ———. 2004. Bare Branches: Security Implications of Asia’s Surplus Male Population. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. Hughes, Diane Owen. 1978. ‘From Brideprice to Dowry in Mediterranean Europe’, Journal of Family History, Vol. 3, No. 3, 262–96. Jin, Xiaoyi, Lige Liu, Yan Li, Marcus W. Feldman and Shuzhou Li. 2013. ‘Bare Branches and the Marriage Market in Rural China: Preliminary Evidence from a Village-level Survey’, Chinese Sociological Review, Vol. 46, No. 1, 83–104. Jin, Xiaoyi, Shuzuo Li and Marcus W. Feldman. 2006. ‘Marriage Form and Fertility in Rural China: An Investigation in Three Counties’, Population Research and Policy Review, Vol. 25, No. 2, 141–56. Jones, Gavin and Bina Gubhaju. 2009. ‘Factors Influencing Changes in Mean Age at First Marriage and Proportions Never Marrying in the Low-fertility Countries of East and South East Asia’, Asian Population Studies, Vol. 5, No. 3, 237–65. Kaur, Ravinder. 2008. ‘Dispensable Daughters and Bachelor Sons: Sex Discrimination in North India’, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 43, No. 30, 109–14. ———. 2012. ‘Marriage and Migration: Citizenship and Marital Experience in Cross-border Marriages between Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal and Bangladesh’, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 47, No. 43, 78–89. Klasen, Stephan and Claudia Wink. 2003. ‘Missing Women: Revisiting the Debate’, Feminist Economics, Vol. 9, Nos. 2 & 3, 263–99. Lee, James and Feng Wang. 1999. ‘Malthusian Models and Chinese Realities: The Chinese Demographic System 1700–2000’, Population and Development Review, Vol. 25, No. 1, 33–65. Lichter, Daniel T., Diane K. McLaughlin, George Kephart and David J. Landry. 1992. ‘Race and the Retreat from Marriage: A Shortage of Marriageable Men?’, American Sociological Review, Vol. 57, No. 6, 781–99. Lichter, Daniel T., Zhenchao Qian and Leannam M. Mellott. 2006. ‘Marriage or Dissolution? Union Transitions Among Poor Cohabiting Women’. Demography, Vol. 43, No. 2, 223–40. Lu Yu and Zhengwu Zhai. 2009. Sixty Years of New China Population. Beijing: China Population Press. McGough, James P. 1981. ‘Deviant Marriage Patterns in Chinese Society’, in Arthur Kleinman and Tsung-Yi Lin (eds), Normal and Abnormal Behavior in Chinese Culture. Dordrecht, Holland: D. Reidel Publishing Company, 171–202. National Survey Research Center at Renmin University of China. 2009. Report on Chinese General Social Survey: 2003–2008. Beijing: China Social Press. Oppenheimer, Valerie Kincade. 2000. ‘The Continuing Importance of Men’s Economic Position in Marriage Formation’, in Linda J. Waite, Christine A. Bachrach, Michelle Hindin, Elizabeth Thomson and Arland Thorton (eds), The Times That Bind: Perspectives on Marriage and Cohabitation. New York: Walter de Gruyter, Inc. 283–301. östör, Kaos, Lina Fruzzetti and Steve Barnett (eds). 1982. Concepts of the Person—Kinship, Caste and Marriage in India. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. China Report 51, 1 (2015): 1–22 22 Yan Wei and Li Zhang N O T FO R C O M M ER C IA L U SE Parry, Jonathan. 1979. Caste and Kinship in Kangra. London, Routledge & Kegan Paul. Peng, Xizhe. 2011. ‘China’s Demographic History and Future Challenges’, Science, Vol. 333, 581–7. Population Census Office of the State Council & the National Bureau of Statistics of China. 2012. Statistics of China 2010 Population Census. Beijing: China Statistics Press. Poston, Dudley L. and Peter A. Morrison. 2005. ‘China: Bachelor Bomb’, International Herald Tribune, 14 September. Qian, Zhenchao. 1998. ‘Changes in Assortative Mating: The Impact of Age and Education, 1970–1990’, Demography, Vol. 35, No. 3, 279–92. Qian, Zhenchao and Samuel H. Preston. 1993. ‘Changes in American Marriage, 1972 to 1987: Availability and Forces of Attraction by Age and Education’, American Sociological Review, Vol. 58, No. 4, 482–95. Shryock, Henry S., Jacob S. Siegel and Associates. 1976. The Methods and Materials of Demography. San Diego, California: Academic Press Limited. Telford, Ted A. 1992. ‘Covariates of Men’s Age at First Marriage: The Historical Demography of Chinese Lineages’, Population Studies, Vol. 46, No. 1, 19–35. Tucker, Catherine and Jennifer Van Hook. 2013. ‘Surplus Chinese Men: Demographic Determinants of the Sex Ratio at Marriageable Ages in China’, Population and Development Review, Vol. 39, No. 2, 209–29. Tucker, Joseph D., Gail E. Henderson, Tian F. Wang, Ying Y. Huang, William Parish, Sui M. Pan, Xiang S. Chen and Myron S. Cohen. 2005. ‘Surplus Men, Sex Work, and the Spread of HIV in China’, AIDS, Vol. 19, No. 6, 539–47. Tuljapurkar, Shripad, Nan Li and Marcus W. Feldman. 1995. ‘High Sex Ratios in China’s Future’, Science, No. 267, 874–6. US Department of State. 2006. ‘Trafficking in Persons Report 2006’, http://www.state.gov/j/tip/rls/ tiprpt/2006 (accessed on 30 March 2013). Wang, Feng and Andrew Mason. 2005. ‘Demographic Dividend and Prospects for Economic Development in China’, Paper prepared for UN Expert Group Meeting on Social and Economic Implications of Changing Population Age Structures, Mexico City, 31 August–2 September. Watson, Rubie S. and Patricia Buckley Ebrey (eds). 1991. Marriage and Inequality in Chinese Society. Berkeley: University of California Press. Yang, Juhua, Yueping Song, Zhenwu Zai and Wei Chen. 2009. Fertility Policy and Sex Ratio at Birth. Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press. Ye Wenzhen and Qingguo Lin. 1998. ‘Zhongguo daling weihun renkou xianxiang cunzai de yuanyin ji duice fenxi’ (Analysis of causes and policies for the phenomenon of old-aged bachelors in China). Chinese Journal of Population Science, Vol. 4, 16–22. Zeng Yi, Ping Tu, Baochang Gu, Yi Xu, Bohua Li and Yongping Li. 1993. ‘Cause and Implications of Recent Increase in the Reported Sex Ratio at Birth in China’, Population and Development Review, Vol. 19, No. 2, 283–302. Zhang, Junsen and William Chan. 1999. ‘Dowry and Wife’s Welfare: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis’, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 107, No. 4, 786–808. Zhang, Weiguo. 2013. ‘Class Categories and Marriage Patterns in Rural China in the Mao Era’, Modern China, Vol. 39, No. 4, 438–71. Zhao, Gracie Ming. 2003. ‘Trafficking of Women for Marriage in China: Policy and Practice’, Criminal Justice, Vol. 3, No. 1, 83–102. China Report 51, 1 (2015): 1–22