Improving International Competitiveness in Australian Business

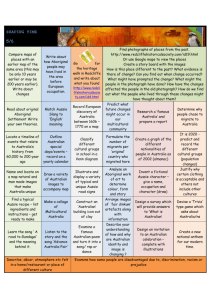

advertisement