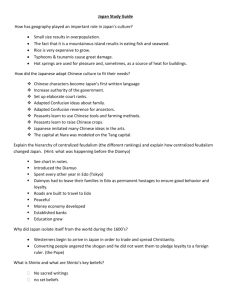

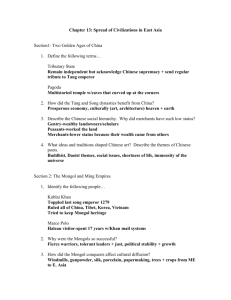

2.6MB - East Asian History

advertisement