D I G I TA L N E W S B O O K

INTRO

PART 1

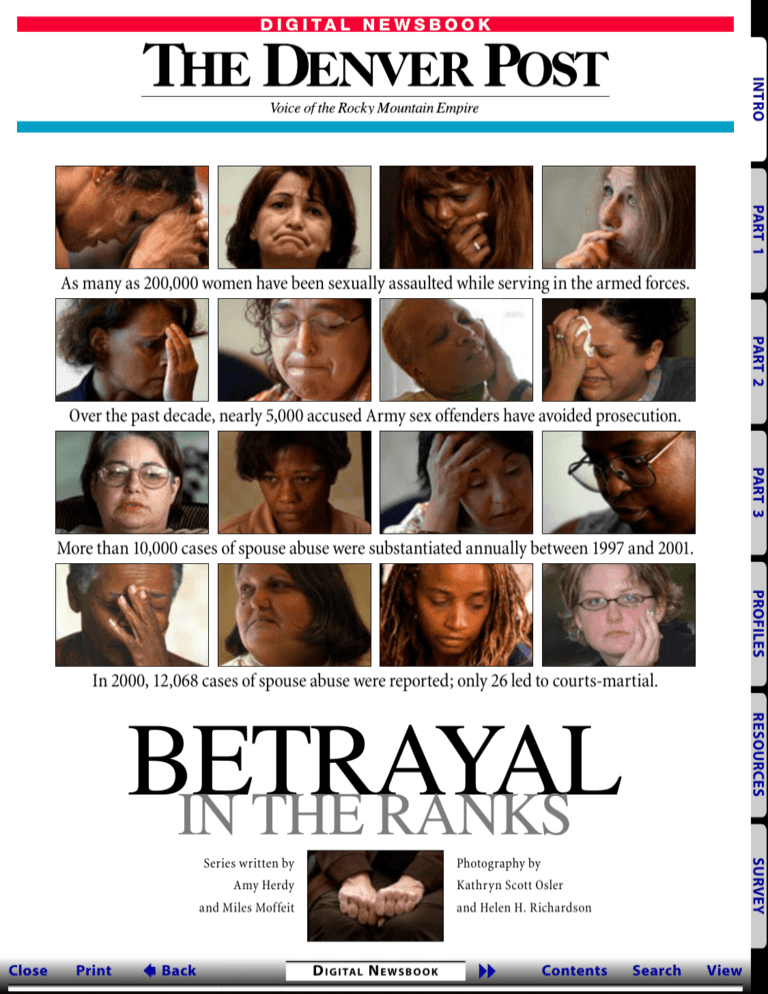

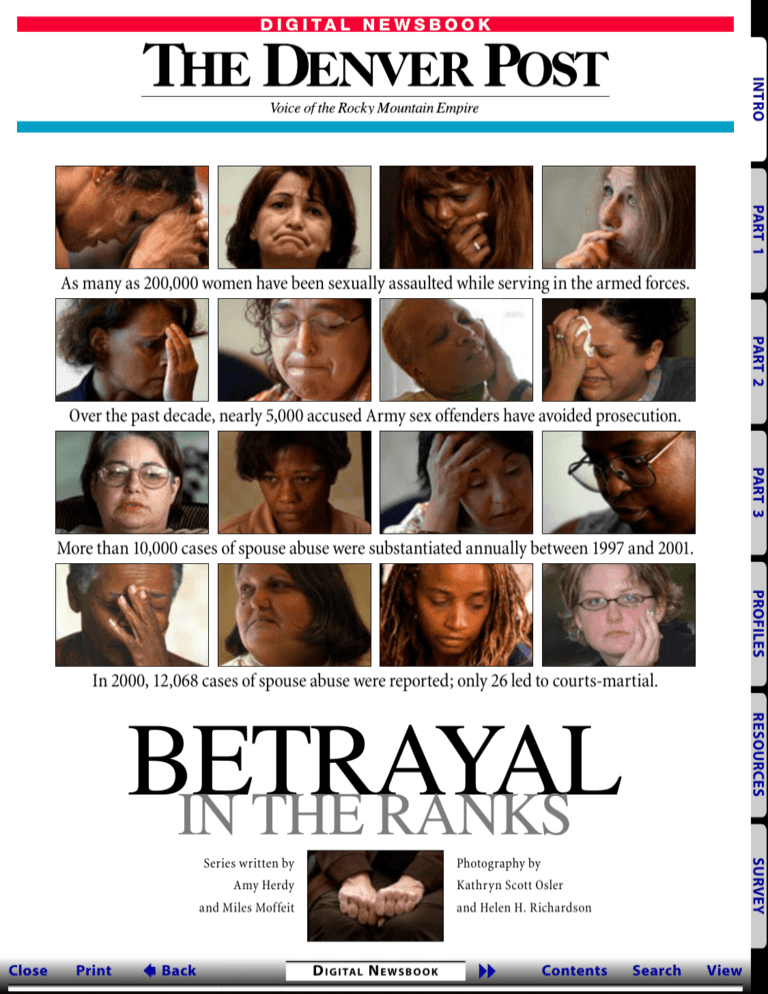

As many as 200,000 women have been sexually assaulted while serving in the armed forces.

PART 2

Over the past decade, nearly 5,000 accused Army sex offenders have avoided prosecution.

PART 3

More than 10,000 cases of spouse abuse were substantiated annually between 1997 and 2001.

PROFILES

In 2000, 12,068 cases of spouse abuse were reported; only 26 led to courts-martial.

Series written by

Kathryn Scott Osler

and Miles Moffeit

Print

Back

7

SURVEY

Photography by

Amy Herdy

Close

RESOURCES

BETRAYAL

IN THE RANKS

and Helen H. Richardson

D I G I TA L N E WS B O O K

8

Contents

Search

View

THE DENVER POST ©2004

BETRAYAL IN THE RANKS

R EPORTERS :

P HOTOGRAPHERS :

Kathryn Scott Osler

Helen H. Richardson

R ESEARCHERS :

Barbara Hudson, Sue Peterson

Copyright©2004 The Denver Post,

1560 Broadway, Denver, CO 80202.

ON THE WEB

DESIGNERS :

Roger Fidler, Rekha Sharma

Close

Print

Back

1

PART ONE

3

8 For crime victims, punishment

8 [ GRAPHIC ] Army sex offenders:

how cases were handled

8 Trauma lingers in victim’s life

PART TWO

19

8 Home front

8 [ GRAPHIC ] Army domestic

violence offenders: how cases

were handled

8 ‘I felt the military abandoned

me’

PART THREE

33

8 Military’s response to rapes,

domestic abuse falls short

7

D I G I TA L N E WS B O O K

8

8 Rape victim thinks of child

‘as gift’

PROFILES

40

8 Coping with anguish and

anger

RESOURCES

58

8 Learn more about sexual

assault and domestic violence

8 About the numbers

SURVEY

61

8 Please let us know what you

think about this series and the

Digital Newsbook concept.

Contents

Search

View

SURVEY

This Digital Newsbook was

designed and produced for The

Post at the Kent State University

Institute for CyberInformation.

More information about this

project can be found at:

www.ici.kent.edu

INTRODUCTION

RESOURCES

DIGITAL NEWSBOOKS

CONTENTS

PROFILES

You can find a multimedia

presentation, audio/video portraits

of the victims, documents from

their cases, and interviews with

the reporters at:

www.denverpost.com

PART 3

All rights reserved. No part of this

Digital Newsbook may be used or

reproduced in any manner without

written permission except in the

case of brief quotations embodied

in articles or reviews.

housands of women have been sexually assaulted in the United

States military. Thousands more have been abused by their

military husbands or boyfriends. And then they are victimized

again. This time, the women are betrayed by the military itself. They

are discouraged from reporting the crimes. Pressured to go easy on

their attackers. Denied protection. Frustrated by a justice system that

readily shields offenders from criminal punishment.

The women suffer for it. Some cannot talk about what happened.

They were killed by men whose violence was allowed to escalate. Other

victims struggle with anger over a trusted system that betrayed them.

The Denver Post spent nine months investigating how the military

handles sexual-assault and domestic-violence complaints. The stories,

originally published as a three-part series (Nov. 16-18, 2003), detail

the newspaper’s findings that military commanders routinely fail to

prosecute those accused of such crimes. The Post also found the victims often are left vulnerable to retaliation and even threats against

their lives because of a lack of victim advocates. More than 60 women

told The Post stories of being beaten or raped while in the military.

Most never found justice.

PART 2

BETRAYAL IN THE RANKS

T

About the series

PART 1

Amy Herdy

AHerdy@Denverpost.com

Miles Moffeit

MMoffeit@Denverpost.com

2

INTRO

THE POST TEAM

INTRODUCTION

INTRO

BETRAYAL IN THE RANKS

A DENVER POST SPECIAL REPORT: PART ONE

For crime victims, punishment

S U S A N A R M E N TA

◆

“I know the way the military structure is;

it will happen to young people coming in. … I want people

not to be like me. I want those girls to come forward. I know

it’s going to hurt them so much more if they don’t.”

For more of Armenta’s story, see Page 45

7

D I G I TA L N E WS B O O K

8

have to be ruined before the military listens?” asked Fictum, who

left the Marines after attempting

suicide later that year.

Parallels to Fictum’s case

emerged last February when

Contents

Search

View

SURVEY

commanders humiliated her and

deprived her of sexual-trauma

counseling. She also was investigated for lying, even after Holguin’s admissions.

“How many young ladies’ lives

8

RESOURCES

Back

PROFILES

Print

PART 3

Close

PART 2

M

arine Joseph Holguin

sank to the floor, hugged

his knees and told the

polygraph examiner that fellow

lance corporal Sally Fictum had

said no.

Accused of raping Fictum, Holguin had maintained in previous

interviews that the act was consensual. But he changed his story

twice after the polygraph results

showed deception.

“Holguin stated he continued

through with the act ... although

she had told him to stop, because

he felt ‘things had gone too far to

stop,”’ an investigator wrote in an

Aug. 11, 1993, report. “Holguin

stated he had made a mistake.”

Holguin was charged with rape.

By October, however, his commander dropped the criminal

case, using discretionary power

granted under military law.

A retired Marine attorney who

reviewed the examination results

for The Denver Post said: “Based

on the documents I’ve reviewed,

they let a rapist walk.”

The 19-year-old Fictum faced

her own punishment. She said her

PART 1

Women who were raped while serving in the military say they

were isolated and blamed for the attacks, while the system they turned to for

help has treated the men who assaulted them far more humanely.

THE DENVER POST ©2004

BETRAYAL IN THE RANKS

PART ONE

4

— Jennifer Bier, a Colorado Springs therapist who has counseled military victims

7

D I G I TA L N E WS B O O K

8

■ These problems take a human

toll. Dozens of veterans told The

Post that being assaulted ruined

their careers and sent them down a

destructive path, including addictions and suicide attempts. Many

carry the scars for life. “When

I looked at the American flag, I

used to see red, white and blue,”

said Marian Hood, a veteran who

said she was gang-raped. “Now, all

I see is blood.”

The Post also found that the

military fails victims of another

abuse — domestic violence. Soldiers who beat their wives or girlfriends usually avoid jail.

To investigate the military

justice system, The Post interviewed victims, reviewed thousands of documents, including

court records, databases, medical

Contents

Search

View

SURVEY

is widespread in the

armed forces, where more than

200,000 women serve. Sketchy

military record-keeping makes it

impossible to quantify. The Pentagon puts the percentage of women

raped in single digits, yet two

Department of Veterans Affairs

surveys in the past decade found 21

percent and 30 percent of women

reported a rape or attempted rape.

The comparable civilian figure is

lack support services, and many are left vulnerable

to pressure and intimidation from

commanders and peers. Despite

a 1994 congressional mandate to

establish victim advocacy programs, the Department of Defense

has a shortage of advocates to help

safeguard women and navigate the

military’s bureaucracy.

RESOURCES

■ Rape

■ Victims

PROFILES

Back

toward sexualassault crimes is routine. Over

the past 10 years, twice as many

accused Army sex offenders were

given administrative punishment

as were court-martialed. In the

civilian world, four of five people

arrested for rape are prosecuted.

Nearly 5,000 accused sex offenders in the military, including rapists, have avoided prosecution,

and the possibility of prison time,

since 1992, according to Army

records. The Air Force released

only limited data, and the Navy

and Marines gave out none. But

civilian victim advocates say the

trends are similar.

“The military system is like

a get-out-of-jail-free card,” said

Jennifer Bier, a Colorado Springs

therapist who has counseled military victims.

PART 3

Print

■ Leniency

nearly 18 percent, according to

a federal survey in 2000. During

congressional hearings in 1991,

witnesses estimated that up to

200,000 women had been sexually

assaulted by servicemen.

PART 2

Close

reporting her sexual assault. “I

was betrayed.”

The Post’s interviews and an

analysis of records found:

PART 1

dozens of U.S. Air Force Academy cadets stepped forward to

report that they faced punishment, attacks on their character

and intimidation after reporting

sexual assault, while their attackers escaped criminal charges.

Military officials said the troubles were limited to the Colorado

Springs school.

But a nine-month investigation

by The Post found that the academy scandal is part of a deeper

problem.

All the armed forces have mishandled sexual-assault cases by

discouraging victims from pursuing complaints, conducting

flawed investigations and depriving victims of support services,

according to interviews with military women and an examination

of records.

Military officers often have

ignored or hidden problems

and findings related to sexual

assaults.

The obstacles to pursuing justice are wrenching, more than 50

sexual-assault victims told The

Post. Many fear retaliation, damage to their careers and being

portrayed as disloyal. And those

who do report are often punished,

intimidated, ostracized or told

they are crazy by their superiors.

“These people were supposed

to be my family,” said Michelle

Swanson, an Army intelligence

specialist who said she was discouraged by a supervisor from

INTRO

“The military system is like a get-out-of-jail-free card.”

THE DENVER POST ©2004

BETRAYAL IN THE RANKS

5

27%

1992

18%

28%

1993

917

53%

25%

756

56%

22%

21%

22%

1994

1995

895

50%

906

54%

19%

22%

31%

1996

705

52%

733

50%

737

51%

27%

28%

22%

25%

21%

22%

27%

21%

31%

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

676

48%

706

38%

18%

44%

2002

Close

Print

Back

7

The Denver Post / Jeffery A. Roberts and Thomas McKay

D I G I TA L N E WS B O O K

8

Contents

Search

View

SURVEY

* Administrative also includes non-judicial Article 15 hearings. Some serious crimes, such as rape, may have

been handled administratively because only a lesser charge could be proved.

** Other includes “no action reported” and where the action was left blank in the database.

Percentages may not add up to 100 percent because of rounding. Click here for more about the numbers

Source: Denver Post analysis of U.S. Army database

RESOURCES

20%

1,090

54%

Action

Administrative*

Military Courts-Martial

Other**

PROFILES

1,177

53%

PART 3

The statistics below are based on the year a crime was investigated, which in some instances may not be

the same the year the crime was committed. The Army says that a spike in offenders in 1996 and 1997 is

partly due to the establishment of a hotline to deal with sexual harassment complaints from Aberdeen Proving

Ground in Maryland. Some of the incidents reported to that hotline occurred before 1996 and 1997.

PART 2

Army sex offenders: how cases were handled

PART 1

consistent evidence that one

exists.

During the past 13 years, the

military has grappled with sexualassault scandals — from the 1991

Tailhook convention to the 1996

Aberdeen Proving Ground investigation to the Air Force Academy

— only to be met by criticisms and

findings of coverup and inaction.

And studies and surveys showed

a military culture that demeans

women.

Even deeper problems emerge in

the stories of women such as Sally

Fictum, Michelle Swanson, Denise

Arroyo and Jennifer Neal. Swanson

to problems and under constant

review.

“It is a bit premature to say that

we believe that changes need to be

made throughout the Services in

the handling of reports of sexual

assault,” the Pentagon statement

said.

“Obviously, the incidents at the

Air Force Academy put the issues

of sexual harassment and sexual

assault in newspapers; so we try

to remain attentive to the current policies and the needs for

improvement.”

But overall the military has not

solved its justice dilemma despite

INTRO

records and Defense Department

memos.

The newspaper also spoke with

two dozen Veterans Affairs sexual-trauma counselors across the

country, who characterized the

women’s stories as credible and

part of a disturbing pattern.

Department of Defense leaders,

including Secretary of Defense

Donald Rumsfeld, declined to be

interviewed for this report. Pentagon officials replied in writing

to questions submitted by The

Post.

They characterized the military justice system as responsive

PART ONE

THE DENVER POST ©2004

BETRAYAL IN THE RANKS

PART ONE

6

Back

7

D I G I TA L N E WS B O O K

8

Contents

Search

View

SURVEY

Print

RESOURCES

Close

PROFILES

Like Joseph Holguin, thousands of accused sex offenders in

the military have escaped imprisonment during the past decade,

military records show.

Many of them avoided criminal

prosecution through administrative actions that offer no possibility of prison or a criminal record.

Fort Benning’s commander was

trying to prosecute a chaplain,

Capt. Robert Peebles, for molesting a 15-year-old boy who was

found wandering the base partially clothed one night.

Peebles confessed to assaulting

the boy, as well as to past sexual

misconduct, court records show,

and prosecutors were preparing

the case for trial.

“I had the taste of blood in my

mouth,” prosecutor James Willson

testified in a lawsuit by the boy’s

family nine years later against the

military and the Catholic Diocese

of Dallas.

The court-martial was derailed,

however, by Delbert Spurlock,

then-assistant secretary of the

Army, according to Gen. James

Lindsay, former commander of the

base where Peebles was stationed.

“Let him resign,” Spurlock said

in a telephone call, according to a

1994 deposition given by Lindsay

in the same lawsuit.

Spurlock was concerned about

bad publicity because another

chaplain had recently been

accused of sexual misconduct,

Lindsay said. “We have just gone

through all of the trauma associated with the press coverage of

this event,” Lindsay recalled Spurlock saying. “We really don’t need

another one.”

PART 3

◆

They faced job-related discipline

such as reprimands, rank reductions, counseling and fines. Some

were allowed to resign.

Since 1992 in the U.S. Army

alone, the cases of 4,801 servicemen accused of offenses ranging

from rape to indecent acts upon

a child were handled administratively, according to records.

That is more than twice the

2,033 suspects who were sent to

court-martial, the military’s version of a criminal trial, for the

same offenses. In 1,283 other

cases, commanders took no action,

and for 1,555 offenders, Army

commanders never reported the

outcome.

Direct comparisons with the

civilian world are impossible

because the justice systems are different. But an analysis by the U.S.

Department of Justice found that

in 1990, civilian officials sought

to prosecute 80 percent of people

arrested on suspicion of rape.

Unlike civilian law enforcement,

military officials rely heavily on

administrative punishments as

an option to prosecution. Military

leaders consider, according to the

Pentagon statement, “the effect of

the decision on the accused and

the command.”

In 1984, top military officials

faced such a decision.

PART 2

was in the Army. Fictum, a Marine.

Arroyo, Air Force. Neal, Navy.

All four not only survived the

punishing rigors of boot camp, they

loved it. Pursuing justice proved to

be a crueler obstacle course.

Although they have never met,

all said they faced threats of punishment and attacks on their

credibility after reporting their

assaults. Their attackers faced

little or no criminal punishment.

The military did not provide them

with a victim advocate, forcing

them to reach outside the armed

services for help and support.

“Most of my clients’ cases are

strikingly similar,” said Beth

Hills, a civilian advocate who

represented three of the women,

as well as more than 100 others

assaulted in the military during

the past decade. “In terms of how

harshly the military treats them,

all you have to do is change the

name on the case file.”

PART 1

— Beth Hills, a civilian advocate who represented three of the women

INTRO

“Most of my clients’ cases are strikingly similar, … In

terms of how harshly the military treats them, all you have

to do is change the name on the case file.”

THE DENVER POST ©2004

BETRAYAL IN THE RANKS

PART ONE

7

INTRO

“The far-reaching role of commanding officers in the

court-martial process remains the greatest barrier to

operating a fair system of criminal justice.”

D I G I TA L N E WS B O O K

8

Contents

Search

View

SURVEY

7

RESOURCES

Back

PROFILES

Print

Dane N. Bogle. Two Air Force

women testified in a hearing that

Bogle sexually assaulted them

two days apart at Dover Air Force

Base, Del., in spring 2001. One of

the victims, 19-year-old Denise

Arroyo, now a civilian, accused

him of entering her room and raping her after she had been drinking with friends. The other victim

also said Bogle sexually assaulted

her in her room.

Bogle was headed for a courtmartial, but instead his commanders allowed him to resign.

Maj. Gen. George N. Williams

approved an “other-than-honorable discharge” at the request of

Bogle and his wing commander,

Scott Wuesthoff, military court

records show.

Wuesthoff noted “inconsistencies” in Arroyo’s story because she

had been drinking, records show.

The other victim, citing religious

beliefs, asked only for an apology,

records show. She could not be

reached by The Post. Both women

supported Bogle’s resignation.

Arroyo said she did so only

after months of pressure from

officers under her commander,

Col. S. Taco Gilbert III. She said

they threatened to charge her

with alcohol violations, but didn’t.

While Arroyo was on leave recovering from her attack, she said,

PART 3

Close

soldier to prosecution. The system

has defenders and critics.

“We have found the UCMJ is

perfectly capable of dealing with

any kind of rape allegation,” said

Col. Craig Smith, chief of the Air

Force military justice division. “I

am completely confident that my

military law lets me get at any

conduct that’s going to arise.”

Officials say administrative

punishments give commanders

useful options.

But in 2001, the Cox Commission, a panel formed on the

50th anniversary of the UCMJ,

noted that “the far-reaching role

of commanding officers in the

court-martial process remains the

greatest barrier to operating a fair

system of criminal justice.”

The commission focused on the

rights of accused soldiers but also

said its review stemmed from “a

near-constant parade of high-profile criminal investigations and

courts-martial, many involving

allegations of sexual misconduct,

each a threat to morale and a public relations disaster.”

Even serial offenders are allowed

to resign with administrative punishments. And, they can slip back

into the civilian world with no

criminal record. Peebles, the military chaplain, is one example.

Another is former Airman

PART 2

Spurlock told The Post: “I don’t

have any memory of it.”

Peebles, who declined to comment to The Post, took a job with

the Dallas diocese after leaving the Army. He resigned in

1986 amid accusations he had

assaulted another boy, according

to court records. The civil lawsuit

was settled. Peebles now lives in

New Orleans and has worked as a

lawyer.

Such leniency is made possible

in large part by a system created

by Congress exclusively for the

military.

In the civilian world, prosecutors decide whether to investigate

and try accused offenders. In the

military, soldiers’ bosses — commanders — make those decisions.

The philosophy behind the

system is to keep soldiers in line

so they know they must answer

to superiors with the power to

convict if they choose not to go

to battle. The approach has been

used by other countries such as

Britain and Canada, though both

scaled back commanders’ powers

in recent years.

The Uniform Code of Military

Justice has been adjusted periodically, sometimes giving the

accused greater protections. Commanders still retain broad powers,

including whether to even send a

PART 1

— Cox Commission in 2001

THE DENVER POST ©2004

BETRAYAL IN THE RANKS

S A L LY F I C T U M

◆

“It’s been my sense of validation.”

PART 3

— Former Marine lance corporal discussing a report on her

attacker’s polygraph test, pictured on the table behind her

D I G I TA L N E WS B O O K

8

Contents

Search

View

SURVEY

7

ber, Col. J.W. Smythe dropped the

criminal case against Holguin.

“They let a rapist walk,” Pat

Gallaher, a military prosecutor for

two decades who now is in private

practice in Buffalo, N.Y., said after

reviewing an official report on the

examination. “I would have prosecuted him.”

Gallaher said the Holguin case

qualified as rape because Fictum

said no.

Smythe, now retired, said he did

not recall the case. He said advisers would have helped him make

the proper call.

“I can’t make a decision like

this without advice from lawyers,”

Smythe said, adding that his job is

fighting wars. “We know how to

blow up tanks.” Smythe also said

RESOURCES

She ran crying into her barracks

room past her roommate and into

the shower stall. The roommate

called authorities.

On Aug. 10 Holguin was wired

to a polygraph machine as an

examiner asked if he had had

sexual intercourse with Fictum.

He said no. “Deception was indicated,” according to a report of the

interrogation.

Holguin changed his story

the next day, saying he and Fictum had consensual intercourse.

Again, “deception was indicated.”

It was then that Holguin

crouched on the floor and admitted Fictum had said no. He signed

a statement detailing the events

that night, records show.

But two months later, in Octo-

PROFILES

Back

PART 2

Print

PART 1

Close

8

INTRO

squadron leader Russell Cutting

told her that he planned to put her

to work in the same dining hall as

her attacker.

“I didn’t want to go back there.

All I could think was that I would

be raped again,” Arroyo told The

Post, adding that Cutting’s remark

persuaded her to quit the Air

Force.

Gilbert, who later went on to

become commandant of cadets at

the Air Force Academy in 2001,

was accused by several cadets of

derailing their cases and pursuing

punishments against them. Gilbert denied that.

Bogle, who now lives in New

Jersey, did not respond to requests

for an interview. Dover officials

and Arroyo’s former supervisors,

including Gilbert and Cutting,

declined to be interviewed. The

Pentagon issued a written statement for Gilbert, saying:

“The Air Force did not discourage Ms. Arroyo from pursuing

this case in any way. We took several extraordinary steps to care

for Ms. Arroyo’s (safety) needs in

this case, including allowing her

to take extended leave.”

Marine Sally Fictum’s experience with military justice began

after a run on the beach with

Joseph Holguin outside Camp

Schwab on Okinawa. It was July

29, 1993. When Fictum stopped to

rest, she said, Holguin threw her

to the sand and raped her.

This was the account Fictum

said she gave military police after

she rushed back up the beach,

struggling to get a foothold in the

loose sand in her military boots.

PART ONE

THE DENVER POST ©2004

BETRAYAL IN THE RANKS

PART ONE

9

INTRO

“These women, over and over again, go through

psychological evaluations, punishments,

and character assassinations.”

D I G I TA L N E WS B O O K

8

Contents

Search

View

SURVEY

7

RESOURCES

Back

On June 14, 2001, Navy sailor

Jennifer Neal, who ranked near the

top of her engineering class, went

to a cookout at the Naval Training

PROFILES

Print

◆

Center in Great Lakes, Ill.

When Jessie R. Capers, a fellow

petty officer, asked her to get him

a beer from his room, Neal agreed.

Capers followed her in.

He grabbed her by the throat,

pinned her to the bed and raped

her, Neal said. Neal then did everything a prosecutor would want her

to do.

She immediately reported the

rape.

She went to a hospital, where

doctors collected DNA evidence

and investigators took photos of

her bloody and torn clothing and

the bite marks that covered her

chest and neck.

But despite all those steps, Neal

was threatened, intimidated and

deprived of basic assistance from

the military that a woman in civilian life could expect, said Beth

Hills, the civilian advocate.

Neal’s experience underscores

another defect in the military justice system, according to the Miles

Foundation, a Connecticut-based

nonprofit victim advocacy organization that has helped more than

5,800 victims of military-related

sexual assault since its founding

in 1987.

“These women, over and over

again, go through psychological

evaluations, punishments, and

character assassinations,” said

PART 3

Close

She copied the file.

She and her parents began a

letter-writing campaign asking

military officials to investigate the

handling of her case. They said

they never got results.

Several months later, Fictum

said, she was granted a medical

discharge due to psychological

trauma from the rape. The charges

of lying were dropped, she said.

Marine officials refused to release

records of the case.

Years later, Fictum said, she forgave Holguin. What she couldn’t

forgive, and struggles with today,

is how the military treated her.

“He (Holguin) admitted his

wrong,” Fictum told The Post,

recounting her story publicly for

the first time. “They never did.”

Last year Fictum, now a thirdgrade teacher, stood in the glare

of her backyard fireplace, tossing

papers into the flames. The medical records went into the fire. So

did most of the criminal-case file.

But Fictum saved Holguin’s

polygraph admission.

“It’s been my sense of validation.”

PART 2

that he would have considered the

“character” of the alleged victim

in deciding whether to prosecute

Holguin.

Reached by telephone in California, Holguin said, “I have nothing to say for your story.”

Fictum said she was never told

about Holguin’s admissions. But

she was investigated for allegedly

making false statements. During

a meeting called by investigators

two months after she reported

the rape, Fictum was told that her

roommate accused her of lying

about it.

“But, I’m telling the truth,” Fictum recalled saying.

Back at her barracks, she began

gathering every pill she could find

from friends and swallowed a

handful.

She awoke in the hospital the

next morning with tubes running

from her nose and stomach.

Released from the hospital, she

resumed a recent assignment as an

aide in the battalion commander’s

office. Alone one day, she noticed

a brown file cabinet labeled “NIS,”

for Naval Investigative Service.

Inside was a file with her name on

it. She flipped through it.

She discovered the account of

the polygraph examination showing that Holguin admitted to forcing intercourse. Her anger boiled.

PART 1

— Christine Hansen, the Miles Foundation director

THE DENVER POST ©2004

BETRAYAL IN THE RANKS

SURVEY

Back

7

D I G I TA L N E WS B O O K

8

Contents

RESOURCES

Print

PROFILES

Siegfried told The Post he did not recall a meeting at which he

allegedly made the above statement. He said he did not seek to

hide information, and he characterized Rosen as “mental.”

Close

PART 3

“(Maj. Gen. Richard Siegfried, left) told us to make sure this

doesn’t come out. He was concerned that this would reflect

negatively on the Army.” — Dr. Leora Rosen, right

PART 2

members.

Yet as soon as Furey left, Siegfried pulled some panel members

into his office and moved to contain what he considered a publicrelations bombshell, Rosen said.

“He told us to make sure this

doesn’t come out,” Rosen recalled,

adding that Siegfried seemed

“concerned that this would reflect

negatively on the Army.”

Siegfried told The Post he did

not recall Furey’s report or the

meeting afterward. He said he did

not seek to hide information out

of embarrassment, and characterized Rosen as “mental.”

“The Denver Post shouldn’t

be writing about this,” Siegfried

said. Other panel members said

they couldn’t recall the meeting or

declined to comment, citing confidentiality agreements.

Rosen, now a senior analyst

for the U.S. Department of Justice, said: “I can fully appreciate that Gen. Siegfried might not

remember every little sidebar that

occurred seven years ago. People

tend to remember events that they

perceive as particularly salient.

That meeting certainly got my

attention, and I kept notes.”

Furey said she isn’t surprised

PART 1

no one will believe them,” Furey

wrote.

“Threatened with bodily

harm.”

“Referral for psychiatric evaluation.”

“Refusal to pursue complaint.”

“No forensic medical exam.”

“Lack of support advocacy

within the command.”

Military women faced intimidation and punishment from commanders, Furey said, and were

vulnerable, in part, because they

had no victim advocates.

Furey said her research found

that victims were isolated and

blamed after their attacks. Victims also were given disciplinary

or psychiatric discharges.

Furey ended her report by urging the panel to recognize the

need for victim advocates, ideally

female service members. She said

the approach should be modeled

after civilian police programs in

which advocates assist victims in

obtaining legal help, counseling

and preparing safety plans.

During Furey’s presentation, the

chairman of the Army panel, Maj.

Gen. Richard Siegfried, expressed

concern, recalled Dr. Leora Rosen,

then a scientific consultant to the

10

INTRO

Christine Hansen, the foundation’s director. “Everything from,

‘You sleep around’ to ‘You’ve got

mental problems’ to ‘You’re a lesbian.’ And in the majority of our

cases, there has been no justice for

the victim.”

After the 1996 Aberdeen scandal in Maryland, in which Army

drill instructors were accused of

raping trainees, defense officials

formed a committee to examine

sexual misconduct.

The next year the committee, known as the Senior Review

Panel, held confidential Pentagon

briefings on the issue. Joan Furey,

director of the VA Center for Women’s Affairs, was among the first to

make a presentation.

Furey told panel members that

women veterans increasingly were

seeking sexual-trauma counseling. VA counselors across the

country were consistently reporting disturbing trends from their

cases.

Furey described more than a

dozen ways women were discouraged from reporting crimes and

derailed from pursuing justice,

according to her report, obtained

by The Post.

“Supervisory personnel stating

PART ONE

Search

View

THE DENVER POST ©2004

BETRAYAL IN THE RANKS

PART ONE

11

D I G I TA L N E WS B O O K

8

Contents

Search

View

SURVEY

7

RESOURCES

Back

PROFILES

Print

20-year-old Neal turned to Hills

for help.

A Navy medical board began

the process of discharging her for

being “unable to adjust to military

service.”

“Clearly ... what (Neal) is unable

to adjust to,” Hills wrote in notes

she kept on the case, “is being

raped by a shipmate on base, and

discovering that this criminal has

more rights, freedoms and protections than she does as a victim.”

Neal said her commander

informed her that charges against

Capers could be dropped because

she had “voluntarily entered his

room.” The Post was unable to

locate the commander.

Hills intervened, complaining to superiors on Neal’s behalf.

Among her complaints, Hills said,

was that investigators interviewed

Neal without an advocate present

and had not made plans to provide

an escort to the trial.

On Dec. 18, 2001, Capers was

convicted of rape at a court-martial. He was sentenced to a reduction in rank, a forfeiture of pay

and three years in prison.

Neal took little satisfaction in

his punishment. She had planned

on a military career. The rape took

that away, she said.

“Before the rape, I felt like I was

in this big balloon and I was sky-

PART 3

Close

Commanding officers were

often the culprits. Fifteen women

said they were assaulted by a

member of their command or a

higher-ranking colleague, heightening their fears of retaliation.

In the majority of the cases the

Miles Foundation has handled,

the assailant had a higher rank,

executive director Hansen said.

Even when their cases are prosecuted, military rape victims say,

they face mistreatment from commanders and others.

The situation becomes “psychological warfare,” said Hills, the

civilian victim advocate. “After

their rapes, they are in no condition to deal with these pressures.

The commands take advantage of

them.”

Neal says that happened to her.

After his arrest, her attacker,

Capers, was released. Though

Neal says she was told his movement would be restricted, he was

able to roam the base freely, and

she was afraid to leave her room to

eat at the dining hall.

On July 12, Neal requested a

meeting with her supervisors,

one of whom threatened to have

her committed to the psychiatric

ward, she said.

“They kept telling me I was

crazy,” Neal said. Unable to find

a victim advocate on her base, the

PART 2

that the panel did not pursue her

findings. A Clinton appointee,

she no longer heads the women’s

affairs center but still works for

the VA.

“The military doesn’t agree

these are issues, that this is a faulty

system,” Furey said. “Therefore,

they won’t take responsibility for

it. The question is, how do you

get a society like the military to

change if they don’t acknowledge

these problems exist?”

Four years later, another military panel raised publicly one of the

findings Furey presented in vain.

Though Congress in 1994

required the military to set up

advocacy programs, today the

majority of installations still lack

victim advocates, according to

Deborah Tucker, co-chair of the

domestic violence task force, which

advised the military to address the

shortage in 2001.

The Pentagon is providing services to victims as “defined in the

law,” according to the statement to

The Post, and intends to expand

the victim advocate program as

funds become available.

Most of the women who told The

Post they were sexually assaulted

in the military said they were discouraged from reporting or they

were too scared to report their

assaults.

PART 1

— Beth Hills, a civilian advocate who represented three of the women

INTRO

“What (Neal) is unable to adjust to is being raped by a

shipmate on base, and discovering that this criminal has more

rights, freedoms and protections than she does as a victim.”

THE DENVER POST ©2004

BETRAYAL IN THE RANKS

PART ONE

12

INTRO

high; I was so happy,” Neal said.

“Then he crashed my balloon.”

◆

◆

“These people were supposed to be my family.

All through basic training, that’s what you’re taught.

Now I know that’s not true.”

D I G I TA L N E WS B O O K

8

Contents

Search

View

SURVEY

7

military police.

Swanson said investigators

questioned her that day but failed

to collect the tampon for fingerprint analysis, or collect DNA evidence. Swanson and her mother

say the additional physical evidence would have strengthened

the case and led to a tougher punishment.

Douglass was sentenced to four

months in prison, documents

show. The Post could not reach

him for comment.

Swanson said her commanders

were more focused on punishing

her for drinking before the assault.

Despite promising they would not

take disciplinary action against

her, they did, Swanson said.

“They were blaming me.”

RESOURCES

The assault occurred on Jan.

18, 2002, after Swanson returned

to her barracks room at Camp Red

Cloud in South Korea from a night

of drinking with friends. Sgt. Jason

L. Douglass walked through her

open door, pinned her on her bed,

removed her tampon and sexually

assaulted her, she said.

“He weighed 200 pounds. I was

drunk,” she told The Post. Swanson said she fought him off and

screamed. She immediately went

to a supervisor, who told her to

“sleep on it,” she said. “He said,

‘This will affect your life and his,”’

she remembers.

Swanson didn’t take his advice.

She wrote a statement about what

happened and told another supervisor, who reported the crime to

PROFILES

Back

MICHELLE SWANSON

PART 3

Print

PART 2

Close

PART 1

The military has been dogged

by criticisms that its investigations were flawed, tainted or

incomplete.

In 1992, a Pentagon report

assailed the Navy’s investigation

into Tailhook for “attempting to

limit the exposure of the Navy and

senior Navy officials to criticism.”

In 1999, a National Academy of

Public Administration panel said

problems abound in sex-crimes

investigations. “Improvements ...

are needed from the unit to the

departmental level.”

The NAPA panel, requested by

Congress, called for better training, organization and recruitment

of women as investigators, and the

addition of sex- crime specialists.

Panel members also raised concerns about commanders’ influence, saying allegations of interference persist. They called on the

Defense Department to “vigorously enforce guidance” against

improper influence.

Four years later, the Pentagon

has yet to act on the recommendations, said William Gadsby, director of management studies for

NAPA. Defense officials say they

have taken steps “to ensure that

appropriate changes have been

made.”

The Post also found examples of

shoddy investigations. U.S. Army

intelligence specialist Michelle

Swanson faults botched treatment of her case as a factor in her

attacker’s light sentence.

THE DENVER POST ©2004

BETRAYAL IN THE RANKS

PART ONE

13

INTRO

Her commanders did not

respond to interview requests

from The Post.

◆

PROFILES

RESOURCES

SHARON MIXON

◆

“I was awarded for valor when I was in Desert Storm, so it

wasn’t like I was a coward. I was a good soldier.”

7

D I G I TA L N E WS B O O K

8

Contents

Search

View

SURVEY

Back

PART 3

Print

PART 2

Close

PART 1

As a young combat medic during

Operation Desert Storm, Sharon

Mixon carried litters of wounded

soldiers, wiped patients’ blood off

her hands, ran at the shrill whistle of an incoming bomb and saw

children die.

None of it, says Mixon, now 33,

was as devastating as when fellow

American soldiers gang-raped

her in June 1991 and a military

police officer rebuffed her effort

to report it.

Mixon, a former member of

the Colorado National Guard, has

been in counseling for more than

two years. Diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder, a mental illness caused by trauma, she

receives VA disability benefits.

During the past decade, thousands of women have streamed

through the doors of VA hospitals and veteran centers, seeking

help in dealing with the trauma

of their rapes. They bring stories

of devastation and loneliness, of

being unable to hold down jobs or

maintain relationships. They are

haunted by fear. Many sleep with

weapons.

For those who never found support in the military after their

rapes, the VA is, finally, a haven.

They can find not only professional

counseling but group therapy with

fellow veterans who they say have

shared a special kind of hell. Dozens of VA counselors told The Post

that the trauma for veterans is

THE DENVER POST ©2004

BETRAYAL IN THE RANKS

PART ONE

14

INTRO

“There is a stigma of mental-health-care counseling

in the military. You can be discharged based

on your mental-health record.”

D I G I TA L N E WS B O O K

8

Contents

Search

View

SURVEY

7

RESOURCES

Back

PROFILES

Print

attempt but to distract herself

from the emotional pain.

The memories flooded back.

Mixon was 21 and waiting with

other soldiers to process out of

Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, after seven

months there. In an apartment

building, soldiers played cards

and talked about going home.

Someone had bootleg liquor in

a water bottle, and Mixon took a

drink. “The next thing I remember is waking up facedown on a

cot. Somebody was on top of me,

penetrating me.” She was disoriented, as if under anesthesia. She

remembers two men holding down

her arms. They told her, “We’ll kill

you if you talk about it.” But she

did.

Hours later, Mixon reported her

assault to a military police officer.

“He said, ‘What did you expect,

being a female in Saudi Arabia?”’

she recalled. “When I told him it

was fellow American soldiers, he

told me if I knew what was best for

me, to keep my mouth shut. I was

too dumbfounded to even react. I

just felt defeated. The other feelings and the anger came afterwards.”

Today, she cries at the memory.

“You know, I was awarded for

valor when I was in Desert Storm,

so it wasn’t like I was a coward. I

was a good soldier.”

PART 3

Close

sation. It is, however, recognized

as a cause of post-traumatic stress

disorder, which does qualify. The

VA defines PTSD as “psychological symptoms that may occur after

a person experiences a traumatic

event” such as a physical assault,

severe accident, natural disaster

or combat. A 1998 VA study says

that sexual trauma may be harder

to cope with than the effects of

combat.

Yet because many sexualtrauma victims don’t report their

assaults, they struggle to live with

the debilitating effects of PTSD

on their own, experts say. Many

abuse drugs or alcohol in an

attempt to numb their pain. They

isolate, unable to trust anyone.

They have problems sleeping and

eating, and may develop physical

ailments including stomach, heart

or gynecological disorders.

“They’ve often experienced

years of trying to cope with

it, years of anxiety they’ve not

understood and cannot explain to

themselves,” said Carol O’Brien,

director of sexual-trauma services

at Bay Pines VA Medical Center in

Florida.

Mixon presented a brave face

to the world until 1999, when she

began having flashbacks. The

tears would not stop. She began

cutting herself, not in a suicide

PART 2

uniquely devastating because they

believed they were in a safe, supportive environment.

“If I was captured, I would have

been mentally prepared,” Mixon

said. “If you got shot, everyone

would be there to sew you up, to

take care of you.”

In many cases, victims told The

Post, no trauma counseling was

made available. Some rejected

counseling because it is not confidential.

“A lot of them wait anywhere

from 10 to 30 years” for therapy,

when they are out of the military,

said Claudia Chavez, a VA sexualtrauma counselor in St. Petersburg,

Fla. “There is a stigma of mentalhealth-care counseling in the military. You can be discharged based

on your mental-health record.”

Since 1999, the VA has provided

free counseling and treatment for

military sexual trauma. VA officials, who spent $6 million on

the treatment last year, estimate

it will cost more than $100 million through 2015. Because of the

stigma surrounding sexual trauma,

said Carole Turner, director of the

Women Veterans Health Program

for the VA, “the information is a

gross under-representation of the

magnitude of the problem.”

Sexual trauma does not qualify

as a disability that brings compen-

PART 1

— Claudia Chavez, a VA sexual-trauma counselor

THE DENVER POST ©2004

BETRAYAL IN THE RANKS

PART ONE

15

INTRO

After her breakdown in 1999,

Mixon enrolled in a residential

treatment program at Bay Pines.

“This program lifted the

world off my shoulders,” she

said, “because I was treated with

respect.”

PART 1

◆

“I was beaten and raped for my country. That

should be enough.”

For more of Hood’s story, see Page 17

7

D I G I TA L N E WS B O O K

8

tub and dumping Hood in. They

dunked her head under water, she

said, until her drill sergeant said,

“We’re done.” Then they left.

It had been dusk when Hood

answered the door. It was deep

into darkness when her friends

returned to find her lying in a bath

of blood and water. “I remember

laying on the stretcher and looking

up at the stars. I remember them

putting me into the ambulance,”

Hood said. “Everything sounded

muffled.”

At the military hospital, Hood

said, she heard a nurse tell a doctor she thought Hood has been

raped.

“Oh, we have girls come in all

the time and claim this. She probably just got into a fight with her

boyfriend,” she recalled the doctor

saying.

Contents

Search

View

SURVEY

assumed they had forgotten something, and opened the door.

Her drill sergeant stood there.

He smashed the door into her

face, she said, bloodying her nose.

Behind him stood four other men.

Dressed in fatigues, they pushed

their way into the room.

The men took turns raping and

sodomizing her, Hood said. They

beat and kicked her, fracturing her

ribs, right knee, nose, right cheekbone and spine. They urinated on

her, burned her with cigarettes,

split her lip and spit on her, while

threatening to kill her.

Hood would later recall it

seemed as though her spirit left.

And so, detached, she watched her

body suffer.

The men ransacked the motel

room, taking money and traveler’s

checks, before filling the bath-

8

RESOURCES

Back

◆

PROFILES

Print

MARIAN HOOD

PART 3

Close

PART 2

Two years ago, Army veteran

Marian Hood sat down at the desk

in her living room in South Boston and wrote a letter to each of

her four young daughters, to be

opened when they turn 21.

Hood’s mother had been Army,

her father Air Force.

She wants the legacy to stop.

There may be no better example than Hood of the human toll

exacted by sexual assault in the

military. Like her, thousands of

female veterans are believed to

have suffered in silence after being

raped by fellow servicemen. Either

they did not report, their story was

never taken seriously or, like Hood,

they were too broken to pursue it.

It is a prison Hood is determined her girls will never know.

She tells them she wants them

to go to college instead of following her path.

“I told them it’s because Mommy

was hurt really bad by some really

mean people, and I don’t want that

to happen to them.”

She was 18 and had just graduated from basic training in December 1987. To celebrate, Hood said,

she and some girlfriends rented a

room at a motel near their base,

Fort Dix, N.J.

Her friends left to go shopping.

Hearing a knock, Hood said she

THE DENVER POST ©2004

BETRAYAL IN THE RANKS

PART ONE

16

INTRO

“That (surgery) would take away

what dignity I have left. Death I can deal with.

Living has been harder.”

D I G I TA L N E WS B O O K

8

Contents

Search

View

SURVEY

7

RESOURCES

Back

PROFILES

Print

press nerves in her legs. Hood’s

medical history is consistent with

her account of a brutal attack and

rape, her orthopedic surgeon said.

And records show that her severe

back pain began then. The VA

diagnosed Hood with PTSD “due

to the in-service stressor of a sexual assault.”

There are other reminders of

the rape: a chipped bone on Hood’s

right knee, seizures from a blood

clot in her brain, rectal problems,

a scar on her lip.

Then, in 1998, Hood faced a new

heartbreak. She was diagnosed

with cervical cancer, which this

year spread to her intestines.

“They’ve given me a time limit

— three years if I don’t do the surgery,” which she refuses to have,

as it would leave her with a colostomy bag. “That would take away

what dignity I have left. Death I

can deal with. Living has been

harder.”

Her instructions for her daughters are explicit. “I have a will.

They join the military, they get no

money.”

And although she is a veteran,

she refuses to fly an American flag.

“The red represents the blood

I’ve shed. The blue represents my

bruises — the way my face looked.

I was beaten and raped for my

country. That should be enough.”

PART 3

Close

“The most exciting thing was to

go down to the riverbed and drive

trucks through the mud.”

Basic training was a breeze

except for her drill sergeant, who

pressed Hood for sex, she said.

She refused and reported him, but

said a supervisor told her she was

delusional and gave her extra duty.

“I was young and naive,” she said.

“I wanted to be all I could be, and

he didn’t see me that way.”

The rape, and her powerlessness

in reporting it, she said, “changed

everything.”

She spent two months in the

hospital. “When I got out, they

gave me a bus ticket, discharge

papers and sent me home,” Hood

said.

She arrived home in February

1988. She never told her mother

what happened, Hood said, “but

she knew.”

Seven months later, her mother

put a .38-caliber revolver in her

mouth and pulled the trigger.

Hood has struggled with guilt over

her mother’s suicide.

“For a long time, I felt like that

was my fault,” she said.

Now 34, she lives with her

daughters, ages 4, 7, 9 and 14, in

government housing.

Her body is a litany of scars.

She has had four surgeries on

fractured vertebrae that painfully

PART 2

Military police arrived.

“They came in, looked me over,

and said they’d be back the next

day,” Hood said. “The MPs didn’t

come back at all.”

Her drill sergeant did. Her second day in the hospital, Hood said,

he brought her yellow daisies.

“He said if I told, no one would

believe me,” Hood said. “I flipped

out.”

Reporters and military officials

could not locate him for comment,

so The Post is not using his name.

A senior officer at Fort Dix at the

time did not respond to requests

for comment.

She was hospitalized two weeks

before calling her mother to say

she was coming home. “She asked

why, and I said, ‘I don’t want to tell

you,”’ Hood recalled. “I begged

her not to come see me because I

didn’t want her to see my face.”

DeLois Hood had been in the

Army. Yet, she would never talk

about it and didn’t want her

daughter to enlist.

“I believe she was raped,”

Marion Lane, 65, Marian Hood’s

father, said of DeLois Hood. During their two years together, Lane

said, DeLois Hood would often

lapse into despair.

Marian Hood, eager to leave

Columbus, Ga., joined anyway. “I

wanted to move away,” she said.

PART 1

— Marian Hood discussing her cervical cancer

THE DENVER POST ©2004

BETRAYAL IN THE RANKS

PART ONE

17

INTRO

PART 1

PART 2

BY AMY HERDY

PHOTOS BY KATHRYN SCOTT OSLER

Print

Back

7

D I G I TA L N E WS B O O K

8

Contents

Search

View

SURVEY

Close

RESOURCES

A

fter she was beaten and raped in the military, Marian Hood said, she had to rethink

everything about her life.

There no longer would be a military career. So she

began working as a secretary for a car dealer. Hood

married and divorced twice. She had two daughters

by her first husband, and two by her second. Her

only son had heart problems and died as an infant.

When her second husband became violent, the

5-foot-3, 116-pound Hood fought back and broke his

nose. “I told the police I would do whatever it took”

to protect her and her daughters, she said.

In 1992, she snapped again. Out with a group of

girlfriends before a wedding, she walked out of a club

to avoid a man who had been pressuring her to dance.

He followed her outside. She said she pulled out a

straight razor and cut him. “I blanked out,” Hood

recalled later. “People came out and pulled me off.”

She was charged with attempted manslaughter.

Her attorney cited her military history as reason for

the attack, Hood said, and she avoided jail in a plea

agreement that included counseling.

That counseling changed her life.

“That was my awakening period,” Hood said. “I

didn’t know who I was. Didn’t know why I was so

angry.”

Now 34, she lives with her daughters, ages 4, 7, 9

and 14, in government housing in South Boston. She

relies on myriad medications.

“I was kicked so bad, my spine is like an ‘S,’ ” she

said of the beating she suffered during her rape.

PROFILES

Trauma lingers in victim’s life

PART 3

Marian Hood hugs her youngest daughter, Gabby, 4, in their apartment. She has left a will that stipulates that her four

daughters not enter the military. ‘They join the military, they get no money.’

THE DENVER POST ©2004

BETRAYAL IN THE RANKS

PART ONE

18

INTRO

Diagnosed in 1998 with cervical cancer that has

spread to her intestines, she undergoes chemotherapy every week. It burns her skin, makes her so sick

at times that she throws up all day. “What keeps me

going are those four kids.

“I wonder why things happened. I would have

been a different person. A lot was taken from me.”

In December 2002, the

Department of Veterans

Affairs awarded Hood disability payments based on

her having post-traumatic

stress disorder. On Aug. 28,

she received notice that she

is losing Medicaid benefits

because her income exceeds

the limit by $82 a month.

She underwent surgery on

her back the week before. Now she is panicked that

mounting medical bills will dash her plans. She had

hoped to buy her sister a business and a house in her

hometown of Columbus, Ga., so her sister could take

care of Hood’s children after she is gone.

“I’m not afraid of death. The only thing I worry

about is my babies. Not being able to hug them or

comfort them. ... But I’m tired of fighting.”

She wants to complete a book of poetry before she

dies. “That will be my legacy.”

PART 1

PART 2

PART 3

Back

7

D I G I TA L N E WS B O O K

8

Contents

Search

View

SURVEY

Print

RESOURCES

Close

PROFILES

A beating and gang rape in

December 1987 left Army

veteran Marian Hood with

a fractured spine and other

injuries, she says. She’s had

four surgeries since then

on vertebrae that painfully

press nerves in her legs, and

she also is battling cervical

cancer that has spread to her

intestines. Hood, seen, at left,

with boyfriend Rey, in her South

Boston home.

INTRO

BETRAYAL IN THE RANKS

A DENVER POST SPECIAL REPORT: PART TWO

PART 1

While civilian

prosecutors crack down

on domestic abuse, the

military emphasizes

counseling and tells

commanders to consider

the accused’s career.

PART 2

PART 3

Home

front

Back

Tears flow when Christina Croom talks about the 1999 killing of her sister,

Tabitha. The Army had backed away from prosecuting Sgt. Forest Nelson,

Tabitha’s boyfriend, but has now reopened the case.

7

D I G I TA L N E WS B O O K

8

Contents

Search

View

SURVEY

Print

RESOURCES

Close

PROFILES

F

ort Bragg police amassed a

3-inch-thick homicide file

to prove Sgt. Forest Nelson

killed his girlfriend, and two military prosecutors said they would

take him to trial.

A witness saw Nelson’s car

backed up to Tabitha Croom’s

apartment door the night she disappeared. And hikers found her

body 500 feet behind his barracks,

among other evidence in the case.

But last year, as the North Carolina Army base faced intense

public scrutiny over a cluster of

domestic-violence murders, Nelson’s commanders shut down the

investigation.

“We all thought he was going to

trial,” said Ann Croom, Tabitha’s

mother. “I will never understand

THE DENVER POST ©2004

BETRAYAL IN THE RANKS

D I G I TA L N E WS B O O K

8

Contents

Search

View

SURVEY

7

RESOURCES

■ Some soldiers go on to kill

their partners after their threats

were known to commanders or

after they were given light punishments for previous assaults. A

PROFILES

Back

military leaves victims

vulnerable. Many military bases

lack advocates to help safeguard

women who have been beaten or

are in danger. Commanders must

react faster to threats of violence,

in part by ensuring that abusers

are kept apart from victims, military consultants say. In 10 cases

reviewed by The Post, an advocate

was not provided, and in some

instances commanders who knew

of assaults or threats downplayed

concerns.

PART 3

Print

■ The

PART 2

Close

■ The military has been slow to

respond to congressional mandates

and other calls for improved investigations. In 1988, Congress told

defense officials to report crimes

to the FBI. Today, the military has

yet to finish the computer system

designed to comply with the mandate. Congress told the Department

of Defense to respond by June 30 to

a task force’s recommendations on

improving military handling of

domestic violence, but Pentagon

officials have yet to comply.

month before Navy sailor David

DeArmond killed his wife and

mother-in-law in 2002, his spouse

sought a restraining order, citing a death threat. Commanders

received a copy of the restraining

order but did not provide her a

victim advocate or restrict DeArmond to the base. Commanders

also contend they did not know

that DeArmond choked his first

wife during a Navy stint in San

Diego. The couple later divorced.

Top Department of Defense

officials refused repeated requests

by The Post to discuss their handling of domestic-violence issues.

Secretary of Defense Donald

Rumsfeld’s office released a statement to The Post saying defense

officials are cracking down on

domestic violence.

“We are working with the services to ensure that commanders take domestic violence seriously and take appropriate action,

including court-martial proceedings when appropriate,” the statement said.

“DOD wants to stop domestic violence because it’s the right

thing to do,” David Lloyd, head

of the military’s Family Advocacy

Program, said in a symposium

presentation last year. “We are

as concerned about this national

problem as anyone else.”

Domestic abuse is pervasive in

the military. Between 1997 and

2001, more than 10,000 cases of

spouse abuse a year have been

substantiated in the armed forces.

Of those cases, 114 were homicides

of adults, according to military

records.

PART 1

■ Batterers in the military are

rarely prosecuted. In the Army,

twice as many accused domestic-violence offenders faced jobrelated discipline in the past

decade as faced criminal prosecution in a court-martial. In 16 murder cases, administrative actions

were taken against the accused,

but the Army provided no details.

The other service branches did not

disclose any data. In a report this

year, a congressionally formed

task force said the Department of

Defense was too lenient with abusers and added: “Offenders must be

held accountable for all criminal

conduct.” Often, offenders are

allowed to leave military service

with an honorable discharge.

20

INTRO

how they could do that. Never.”

The military investigative file

obtained by The Denver Post does

not explain why Nelson’s commander shelved the case, using his

discretionary power under military law. The documents indicate

Nelson faced administrative punishment, noting that “disciplinary

action is pending.”

The Army reopened the murder

investigation last summer after The

Post raised questions about the case

and uncovered evidence of violence

in Nelson’s previous marriage.

The Croom homicide and other

domestic-violence incidents, a

nine-month Post investigation

found, reveal a secretive justice system tightly controlled by

commanders that routinely fails

to prosecute domestic-violence

offenders and creates obstacles for

victims, sometimes leaving them

unprotected.

Some end up dead.

The military often mishandles

cases of domestic violence, as well

as sexual assault, according to a

review of thousands of military

documents and interviews with

dozens of victims.

Among the The Post’s findings:

PART TWO

THE DENVER POST ©2004

BETRAYAL IN THE RANKS

PART 3

33%

34%

1992

1993

27%

26%

168

49%

139

53%

144

51%

134

52%

24%

25%

25%

23%

29%

24%

28%

27%

23%

37%

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

24%

26%

17%

31%

1994

1995

1996

140

43%

118

40%

129

40%

12%

48%

2002

Close

Print

Back

7

The Denver Post / Jeffery A. Roberts and Thomas McKay

D I G I TA L N E WS B O O K

8

Contents

Search

View

SURVEY

* Administrative also includes non-judicial Article 15 hearings. Some serious crimes, such as rape, may have

been handled administratively because only a lesser charge could be proved.

** Other includes “no action reported” and where the action was left blank in the database.

Percentages may not add up to 100 percent because of rounding. Click here for more about the numbers

Source: Denver Post analysis of U.S. Army database

RESOURCES

21%

159

48%

Action

Administrative*

Military Courts-Martial

Other**

PROFILES

20%

186

49%

PART 2

The statistics below are based on the year a crime was investigated, which

in some instances may not be the same the year the crime was committed.

229

46%

PART 1

Violence to examine how the military handles abuse cases.

The 24-member task force, with

civilian and military members,

concluded this year that the system needed an overhaul to hold

batterers accountable, protect victims and train commanders.

According to the Defense

Department statement to The

Post, military officials agree with

most of the recommendations and

are in the final stages of reviewing

them.

If the military does change its

approach, it will be overcoming a

historical tendency to downplay

the severity of domestic-abuse

problems, said Deborah Tucker,

Army domestic violence offenders:

how cases were handled

239

48%

21

INTRO

Few studies have compared

military domestic-abuse trends

with the civilian world. One study

performed for the Army in the

early 1990s suggested that the

prevalence of the crimes could

be twice as high as in the civilian

world. Other studies have concluded rates are similar. A 1999

study found that the Army showed

a higher rate of cases with severe

injuries.

A series of spousal killings at

Fort Campbell in Kentucky during

the late 1990s, as well as concerns

raised by The Miles Foundation

and other advocacy groups, led

Congress in 2000 to create the

Defense Task Force on Domestic

The military defines domestic

violence as acts of physical, sexual

and emotional abuse. For statistical purposes, however, the military often does not count intimate

partners such as girlfriends as

domestic-abuse victims, contrary

to the civilian world.

The rate of reported spouse

abuse in the military declined

from 1997 to 2001 - from 22 per

thousand active-duty personnel

to 16.5 per thousand. But memos

show that Pentagon officials

believed in 2001 that the decline

was caused in part by fears that

reporting the crimes could hurt

careers, and that commanders

were not reporting all incidents.

PART TWO

THE DENVER POST ©2004

BETRAYAL IN THE RANKS

PART TWO

22

INTRO

“It’s a sad commentary on the military justice

system that we still do not treat domestic violence

like other serious crimes.”

◆

7

D I G I TA L N E WS B O O K

8

Contents

Search

View

SURVEY

Back

RESOURCES

Print

PROFILES

Close

such crimes were incomplete.

Separate data the Army provided to The Post this summer

show that more than 800 soldiers

faced administrative penalties

during the past decade, more than

twice the 400 who went to courtmartial. Specific punishments

were not disclosed. The outcomes

in 320 cases were blank.

In the most severe domesticviolence cases — murder — 16

accused offenders were handled

administratively, the records

show. An equal number faced

court-martial proceedings.

The outcomes for 14 homicide

cases were blank.

Defense Department task force

members were frustrated when

they encountered similarly incomplete data early in their review,

said Tucker, the panel’s co-chair.

“We were stymied by a lack of

information,” Tucker said. “Information came back to us blank or

blacked out. This said to me that

(military officials) really don’t

want to know how bad the problem is.”

The Pentagon says its solution to the poor tracking of crime

— called the Data Incident Based

Reporting System — should be

fully operational next year.

After touring several military

installations, task force members

PART 3

While civilian prosecutors in

the past two decades have cracked

down on abusers, the military

emphasizes counseling and

instructs commanders to consider the effect of punishments on

careers of the accused.

Often, offenders are given

administrative punishments. Or

no discipline at all.

“It’s a sad commentary on the

military justice system that we still

do not treat domestic violence like

other serious crimes,” said Casey

Gwinn, a San Diego prosecutor

and member of the domestic-violence task force. “When was the

last time somebody robbed a bank

and expected only counseling?”

The task force found the system

severely flawed, preventing true

accountability for offenders whose

violence typically persists, leaving

victims on their own.

“Commanding officers must

ensure that the institution, not

the victim, is responsible for hold-

ing the offender accountable,” the

task force report said.

Civilian prosecutors place a

high priority on convicting abusers, said Denver District Attorney

Bill Ritter, who chairs the board

of the American Prosecutors

Research Institute. Two decades

ago, domestic violence was too

often considered a family matter,

he said.

“Now there is a focus nationally

on the scourge of domestic violence,” Ritter said. “Prosecution is

part of it.”

Batterers are rarely prosecuted

in the military, but the exact picture is obscured by flawed recordkeeping and the fact that commanders have failed to report

punishments of their service

members to a central office, documents show.

In 2000, 12,068 cases of spouse

abuse were reported to the military’s Family Advocacy Program, which handles abuse cases,

according to a Defense Department memorandum submitted to

Congress.

Of the 1,492 cases investigated

by military police, the memo

shows, only 26 led to courts-martial. The outcomes of 983 incidents

were not reported by command

officials. The memo also states

that databases designed to track

PART 2

co-chair of the now-defunct task

force whose recommendations are

being considered.

“Philosophically, domestic violence has been viewed by the military as a case of family dysfunction, not through a lens of criminal

behavior.”

PART 1

— Casey Gwinn, a San Diego prosecutor

THE DENVER POST ©2004

BETRAYAL IN THE RANKS

LAURA SANDLER

◆

“All we have to protect us are the laws and the systems

that are put in place, and when they are neglected,

women not only die but they are left with lifelong

scars that may or may not heal.”

For more on Sandler’s story, see Page 48

8

Contents

Search

View

SURVEY

D I G I TA L N E WS B O O K

ment, records show. Tampa police

arrested him on a felony charge

of battering a pregnant woman,

which was later reduced to a misdemeanor because Hine would not

cooperate.

Base officials weren’t concerned

about the violence, Coleman said

in a telephone interview with The

Post. “They were mad at me for

bringing negative publicity.”

A supervisor sent him to a Mental Health Skills class.

“I told him I didn’t really need

it because I wasn’t starting anything,” Coleman said. “He told me

it would be in my best interests to

ework things out.”

RESOURCES

7

8

PROFILES

most sophisticated batterers today

avoid accountability in the military. They’re really sorry. They go

to counseling. They want to save

their career.”

James Coleman, a Marine