Writing the Paper revised

advertisement

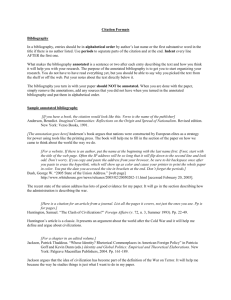

R E S E A R C H PA P E R A S S I G N M E N T W R I T I N G T H E A R T H I S T O R Y PA P E R Rough Draft Due, Tuesday October 23 Final Paper Due, Tuesday November 6 All papers will be collected at the beginning of the class period. If you come to class late, it is your responsibility to turn in your paper. Furthermore, if you miss class, and only show up to turn in your assignment, it will still be considered late. If you must be absent the day your paper is due, you may drop it off early to my mailbox - S2-202. Assignments will not be accepted by email. Do not accept a zero for your paper. It is better to turn in your paper late than not all. However, please note that there will be a 10% penalty for each day late. No papers will be accepted the week of finals. Formatting Guidelines • Pick 3 of the 5 categories, listed under Kinds of Art History Papers, to include in your research paper • You can choose any work of art/architectural building as long as it within the timeline of the course. • Art 101 - Prehistoric to Gothic • Art 102 - Late Gothic to Contemporary • 4 - 6 pages • Please note that you must have 4 full pages. • One inch margins all around • 12 point type font • Double spaced • Black ink on white paper • Do not put your paper into a folder or a binder. • A minimum of 4 sources. • The textbook does not count as a source. • If you use a website as a source, it must be cited correctly. • Print your research paper early and not the day it is due. • The artist’s entire name is written the first time he/she is mentioned. • Illustrations are located after the bibliography and not within the research paper. • Illustrations do not count as part of the 4 - 6 pages. • All illustrations should be numbered and labeled. • Artist, title (in italics every time is it written), year, medium, where it is located (museum, cathedral, etc.) and city. • For example, 1. Michelangelo Bournarroti, David, 1501-04, marble, Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence. • The first time an image is mentioned in your paper, provide the title and figure number. • (Figure 1) • If you provide details of your image, you may use the same format mentioned above. • Any writing style (Chicago or MLA) will be accepted as long as it is consistent 1 throughout the entire paper. • Be sure to include footnotes and a bibliography. Challenges and Purposes What distinguishes Art History papers from the papers you might be asked to write in other courses? Perhaps the biggest difference creates the biggest challenge: in Art History papers, you must be able to create an argument about what you see. In short, you have to translate the visual into the verbal. To do this you must first understand the “language” of the discipline - that is, you need to familiarize yourself with the terms and concepts necessary to describe a work of art. Second - and perhaps most important - you need to learn not only to describe what you see, but also to craft your description so that it delivers some argument or point of view. A good Art History paper will not simply offer a haphazard description of the elements of a painting, sculpture, or building. You must consider what it is you want to say about a work of art and use your description to make that point. In short, you must master the art of simultaneously analyzing and describing the work of art you have chosen to discuss. Introduction Example Here is an example an introduction, written by an Art History student, Amber Smith. Note how Smith introduces Michelangelo’s adolescent years to the reader. Furthermore, there is a clear thesis statement. It is important for the reader to understand what is going to be discussed throughout the paper. Michelangelo spent his earliest years living on a farm, with a couple that took care of him as if he was their own son. Occasionally, Michelangelo would go into the city of Florence to visit another family, which later on turned out to be his real family, but he would always return to the countryside and his life on the farm. Then, one-day in the 1480s (the actual date is uncertain), his real father, Ludovico, came to the farm and took Michelangelo to permanently reside in Florence. Now, his surroundings were unfamiliar and he never returned to live in the farm that he once called home. In Florence, Ludovico sent Michelangelo to grammar school. However, Michelangelo would often sneak off with his friend Francesco Granacci to visit artists at work in various locations throughout the city. When Ludovico found out about his son’s truancy and desire to draw, he was livid. To Ludovico, being an artist was similar to working as a stonemason. He hated the art of design and saw it as a disgrace to the family. Ludovico disapproved of the path that Michelangelo was taking and turned to a possible distant relative, Lorenzo de’ Medici, for advice. Lorenzo, known as Il Magnifico, was a prosperous banker in Florence who encouraged Ludovico to place Michelangelo into the workshop of Ghirlandaio. However, Michelangelo’s apprenticeship abruptly ended as he found himself being sent to the Medici garden of San Marco to study sculpture and classical antiquity. It was here that Michelangelo’s creative talents began to flourish. Furthermore, he also had the opportunity to develop a personal and artistic relationship with Lorenzo. 2 There has been a lot of speculation surrounding Michelangelo’s youth and his artistic training. Even while he was living, the biographers of his time, Giorgio Vasari and Ascanio Condivi were rewriting Michelangelo’s life. Therefore, this paper will be split into two sections. The first part will focus on Michelangelo’s adolescent years and the events that helped shape his life as an artist, beginning with his birth and with the stonemasons in Settignano. Then, I will discuss how Michelangelo was taken from Settignano and brought to Florence to live with his real family when he was ten years old. This will parlay into Michelangelo’s struggle to find his place within the family as he befriended Francesco Granacci. This segment will end with Michelangelo’s apprenticeship with Domenico del Ghirlandiao. The second part of my paper will focus on how Michelangelo’s experiences in the garden of San Marco, with the sculpture teacher Bertoldo di Giovanni, fellow student Pietro Torrigiani, and the Medici palace with Lorenzo de’ Medici influenced his earlyworks of art – the Faun, the Madonna of the stairs, the Battle of the Lapiths and Centaurs. Note how all of the details in these paragraphs support Smith’s thesis. The writer offers no details that are irrelevant to this argument. Kinds of Art History Papers Sylvan Barnet, A Short Guide to Writing about Art, identifies five categories of the Art History paper. Once you have chosen a work of art or architectural building, choose three from the list of five categories to include in your paper. The following is an example of a possible thesis statement. The focus of this research paper will be on Michelangelo’s sculpture of David. First, biographical information on the artist will be discussed. Second, the sculpture of David will be placed within its sociological context. Last, the iconography of David will be examined. Formal Analysis (Chapter 3, Sylvan Barnet p. 46) Formal analysis is an examination of the form an artist produces. That is, an analysis of the work of art - line, shape, color, texture, mass, and composition. These things give the stone or canvas its color, its expression, its content, and its meaning. The following example is from Amber Smith’s paper on Michelangelo’s Battle of the Lapiths and Centaurs. Michelangelo created a plethora of classical figures in different postures, spaces, and movements. In the foreground they were carved in high relief while the figures in the background hardly emerged from the marble. Furthermore, Michelangelo revealed his interest in the male nude as can be seen in the gestures of his figures. For the first time he was demonstrating that he could handle numerous figures within a single work. In the central group of figures Michelangelo sculpted Hippodameia bent over as her hair is being pulled. Some of the figures in the upper area of the relief were polished while other portions of the surface between the figures were left rough. This transformation between the rough and the smooth areas show traces of Michelangelo’s hand as he pounded the chisel into the marble. Perhaps this sculpture was left unfinished because Lorenzo had taken ill and was dying. 3 Sociological Essay - looks at a particular historical era and asks how that era influences a particular work or artist. For instance, a sociological essay might explore how Michelangelo’s interest in working with marble could have stemmed from his experiences with the Medici and the San Marco garden. Biographical Essay - explores the relevance of an artist’s life to his or her art. For example, Giorgio Vasari gave Michelangelo the first volume of Vasari’s Lives as a gift for his seventy-fifth birthday. A biographical essay might note how Vasari saw Michelangelo as a supreme being and compared other artists to him. Iconography (Chapter 11, Sylvan Barnet p. 260) Iconography (which means, literally, “image writing) is a work that seeks to identify images through an exploration of the symbols in a piece of art. Or, the study of visual images and symbols within their cultural and historical contexts. One of the portraits by Rembrandt, entitled The Assassin, appears to be a man holding a knife. However, an exploration of the painting’s symbolism (the presence of a knife) reveals that this figure might be more accurately identified as Saint Bartholomew. Another example of iconography would be an altarpiece with an image of lilies. When these flowers are accompanied by the Virgin Mary, it is a symbol of her purity. Iconology - (Chapter 11, Sylvan Barnet p. 262) Iconology (which means, literally, “image study”) uses literary and other texts to interpret a work. In short, iconology tells us the purpose of an image. Or, iconology examines the social or political tendencies of a period or country. For example, such an essay might use translations of hieroglyphs from Ancient Egyptian tombs to shed light on a pharaoh’s life. HINTS FOR PREPARING A GOOD RESEARCH PAPER AND CONDUCTING ART HISTORICAL RESEARCH Preparation of a Research Paper A research paper is based on the student’s own observations, as well as the relevant sources consulted during the course of the student’s research. The student needs to take careful and accurate notes of the all the useful information he/she can find, organize the results of the study, and then present the results in essay form. The evidence—that is, the facts, figures, and opinions that are cited or quoted in order to illustrate and support the conclusions—must be documented. Documentation Chapter 12, Sylvan Barnet p. 271 - 292, Finding Material Documentation applies to the conventional use of footnotes and bibliography required as part of any scholarly paper. Good documentation provides proper acknowledgment of “borrowed” materials and permits the reader to verify the findings of the writer. Papers that are inadequately or inaccurately documented are not acceptable as college work (see also final paragraph on plagiarism!). 4 Assembling a Preliminary Bibliography “Bibliography” refers to the list of sources you have consulted and used in preparing your research paper. The first step in a good research paper is to find as many sources (books, articles) you can that are relevant to your topic. For research: 1) Start with general survey texts, or textbooks on specific periods to begin to assemble a bibliography. The Dictionary of Art is also available on-line (as Grove Art Online); see below, under number 3, for further information about on-line references. 2) Look for a monograph (detailed written study) on your artist, or a text on a relevant group of artists (perhaps from the same city, region, or time period). 3) The ELAC library has an online database - Gale Virtual Library. Check here to look at the library’s collection - http://www.elac.edu/departments/library/index.asp. You can also search the Grove Dictionary of Art, for information and bibliography. You can search this databases on terminals connected to the campus network; you can also search them from home, as long as you have an ACE account and login information. Go to the the library home page - http://www.elac.edu/departments/library/index.asp. Click on Online databases (under Find Articles and More). Then, click on Grove Art Online. If you find references to articles that may be relevant to your research, don't be intimidated by foreign journals with names in other languages. Usually European journals publish articles in English as well as other languages. On the top right hand corner there is an option to print or email the article. 4) You might also find some useful research information and bibliographic sources on certain Websites; however, be aware that most of the information you will find on Websites is highly superficial, and is sometimes completely inaccurate. Website information should be used only to supplement written sources (books and articles), and NEVER as a primary source. If your paper refers mainly to Website sources, and not to written sources, your grade will suffer! For basic information supplied by our local museums, check their websites: The following websites will be accepted as a source: • J. Paul Getty Museum [http://www.getty.edu/museum/] • L.A. County Museum of Art: [http://www.lacma.org/] • Norton Simon Museum [http://www.nortonsimon.org/] • San Diego Museum of Art: [http://www.sdmart.org/] • Metropolitan Museum of Art, Heilbrunn Timeline of Art: •[http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/world-regions/#/06/Europe] • National Gallery of Art: [http://www.nga.gov] • Webmuseum Paris: [http://metalab.unc.edu/wm/] • Web Gallery of Art: http://www.wga.hu/index1.html • Art History Resources on the Web [http://witcombe.bcpw.sbc.edu/ARTHLinks.html] • Mother of all Art History Links Pages: [http://www.umich.edu/~motherha/] 5 •Art History resource: [http://arthistoryresources.net/ARTHLinks.html] • Travel websites • University or State schools Sites to AVOID as a source of incorrect information and will not be accepted as a source: • World Art Treasures [http://sgwww.epfl.ch/BERGER/index.html] • Anything Wikipedia • Google • Yahoo • Travel Blogs • Flicker (or any other site that allows people to post their photos) 5) Once you have assembled a list of books and articles, try to read the most recent sources first, as that will put you in touch with the most current ideas and information. Pay careful attention to any sources listed in footnotes or in the bibliographies of the things you read, since this will help you find more references. If you can’t find a particular book or journal in our library, follow up in the following ways: a) Many journals that are not in our library (and even some that are) can now be accessed on-line. Another online source is ARTstor. This database has information from museums and university collections of paintings and photographs - https:// libproxy.elac.edu/login?url=http://www.artstor.org. You will need to register in order to gain access to ARTstor. b) Try another library that has larger holdings in art history, such as on the campuses of UC Irvine or UCLA (the latter has a separate, non-circulating art library, which means you will find just about everything you may need there, but you must read the material in the library). You can access the UC Library catalog (“Melvyl” system) via the “California Digital Library” [http://melvyl.cdlib.org/]. c) Use the Inter-Library Loan service in our own library; you can get books through ILL for a two-week period. If you would like to use this service, you need to speak to a librarian in the library. It will take about five days to receive the requested material. Reading Sources When you are consulting sources, make sure you take down complete and accurate information relevant to your topic. For the footnotes and bibliography, you will need to start with the author’s name, the full title, and the place and date of publication, and the name of the publisher. When you copy any information, make sure that the source of every note is fully and specifically identified, especially the precise page number. Take notes that are clear and intelligible; record your relevant opinions, judgments, questions, etc. in square brackets to distinguish what is yours from what belongs to your source. 6 Suggestions: 1) Do not take notes haphazardly as you go along. Read an article or book through first and then go back to take your notes after you have seen what it is about, from what point of view it is written, and upon what topic the author is speaking authoritatively. 2) Be sure that your notes are accurate. Verify the source and the page reference. Use quotation marks for all quoted matter: verify spelling, capitalization, and punctuation. 3) If you include quotations in your final paper, use them sparingly—most relevant information should be expressed in your own words. Where you do quote, it must be accurate; spelling, punctuation and paragraphing must conform exactly with the original. Also, quote fairly; do not use a quotation in such a way or in such a form as to distort the meaning it had in its original context. Also, introduce the quotation in a way to give some indication of its context. That is, work the quotations carefully into your text, without distorting either your own syntax or that of the quoted material. Always supply a transition to a quotation, so that your reader will understand your reason for quoting. If your quote is longer than two lines, it must be indented and single spaced. For writing term papers: Uses of footnotes: When you must footnote: a) exact quotes (using quotation marks) b) specific information which may not be generally known, and which you are citing directly from your source c) you use ideas or opinions which are the contribution of a particular author, or paraphrase an author's wording in such a way that the author's ideas and opinions are being used (these are among the trickiest aspects of footnoting!) Other uses of footnotes: a) to expand upon the text you have written—perhaps introducing facts, ideas or opinions which are not immediately relevant, but which you (and, perhaps, the reader) may find interesting b) as a “disclaimer”—to cite an author or source to show that you are aware of the work, but may not agree with the ideas, or find it irrelevant. Functions of footnotes: a) to show that you have done your homework—i.e., that you have read the proper sources, and know what you are talking about in your paper b) to tell the reader where he/she can look for further information on your topic c) to indicate most clearly what your original contribution to your paper is—that is, to differentiate between the ideas, information or opinions you have acquired from your sources and what you have come up with yourself. For students who are to be graded on term papers, this is perhaps the most important aspect of using footnotes properly. 7 Footnotes must be accurate. Page references must be precise. Proper names must be correctly spelled; titles must be underlined accurately (or in italics), and dates must be exact. Attend carefully to the numbering of footnotes. Number your footnotes consecutively throughout your paper. That is, the first footnote is numbered “1,” the next is “2”… “3”… etc.; each footnote has its own number. This rule applies even if you’re referring to the same source. If that’s the case, you need only repeat the last name of the author and the page number (see the form instructions detailed below), but the footnote has the next number in the sequence. In your text, mark footnotes by a superscript numeral placed after the material to be documented. If a note is intended to identify a whole block of material from a single source, place the numeral at the end of the first reference that depends upon the source; if necessary, word your reference so that your reader will understand the extent of your dependence. When you check your final draft for accuracy, make sure that you have included all superscript numerals and their matching footnotes The footnotes themselves may be placed either at the foot of the appropriate page, or as endnotes following the text of the essay. Follow the form indicated below, with these specifications: 1) Use paragraph indentation and write each footnote in the form of a single paragraph. 2) Use single-spacing within footnotes and double-spacing between footnotes. 3) Note that the author’s name in a footnote is given in normal order (i.e., first name/last name); in a Bibliography, the author’s last name is given first so that it can be listed alphabetically. Note also the difference between the first reference, in which complete information must be provided, and subsequent references, in which only the minimum information needs to be given. Examples of acceptable footnote form (Art Bulletin/Chicago Manual version): Sample Text: Since parts of the altarpiece have been lost, there has been debate among scholars about the original appearance of the polyptych, especially regarding the relationship of the central panel with the side panels that are known to have contained saints. On the basis of shadows visible in the central panel, John Shearman proposed that there was a continuous field connecting the main panels.1 On the other hand, James Beck proposed that, on the basis of the surviving documentary evidence, there would have been a conventional separation between the center and side panels, reinforced by pilasters in the frame.2 Footnotes: [At bottom of page, or on separate page(s) at end of paper] 1 John Shearman, “Masaccio’s Pisa Altarpiece: An Alternative Reconstruction,” Burlington Magazine 108 (1966): 452-55. See also John Spike, Masaccio (New York: Abbeville Press, 1996), 200. 8 2 James Beck, Gino Corti, Masaccio: The Documents (Locust Valley: J.J. Augustin, 1978), 17-18. Also Spike, 200201. (Note that underlining a title is an acceptable alternative to using italics.) The first reference in the footnote must have a full reference (author, name of work, place of publication, etc.), but subsequent references to the same source can merely list the author's last name and page number. The proper citation to a book by a single author can be as follows [form=author's name, title of book (either italicized or underlined), parentheses that enclose (place of publication: name of publisher, date of publication), page number(s)]. Example: John Spike, Masaccio (New York: Abbeville Press, 1996), 200. Proper citation to an article in a footnote [form=author's name, title of article in quotation marks, name of journal (italicized or underlined), volume number of journal, parentheses around (year of journal) followed by a colon: page number(s)]. Example: John Shearman, “Masaccio’s Pisa Altarpiece: An Alternative Reconstruction,” Burlington Magazine 108 (1966): 452-55. Note that in the citation above, the name of the work of art in the title was also italicized. Remember that after the first footnote containing the complete citation, all subsequent references to the same source can be brief: Author’s last name, page number(s). Example: Spike, 200-201. Bibliography Your Bibliography should consist of an alphabetized list (by author's last name) of all of the sources you have referred to in your footnotes, placed on a separate page at the end of your paper; examples of proper Bibliography form (Art Bulletin version) [note each reference is single-spaced, but there should be a space left between each reference]. Note that for books, the page numbers consulted need not be listed in the bibliography; for articles, the full range of page numbers (for the entire article) must be listed. Beck, James, with Gino Corti, Masaccio: The Documents (Locust Valley: J.J. Augustin, 1978). Shearman, John, “Masaccio’s Pisa Altarpiece: An Alternative Reconstruction,” Burlington Magazine 108 (1966): 449-55. Spike, John T., Masaccio (New York: Abbeville Press, 1996). IMPORTANT NOTE If you have questions about citing, download the Bibliography pdf files from www.ArtMusicHistory.com. Failure to refer to your sources properly may result in plagiarism! Plagiarism is defined as “the act of using the ideas or work of another person or persons as if they were ones’ own, without giving credit to the source… Examples of plagiarism include, but are not limited to, the 9 following…failure to give credit for ideas, statements, facts or conclusions with rightfully belong to another; in written work, failure to use quotation marks when quoting directly from another, whether it be a paragraph, a sentence, or even a part thereof; close and lengthy paraphrasing of another’s writing….” You must include footnotes and a bibliography! If there is clear evidence of plagiarism in your term paper, you will receive a failing grade! 10