Quasi-Pareto Social Improvements

advertisement

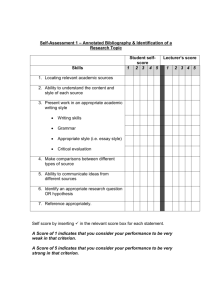

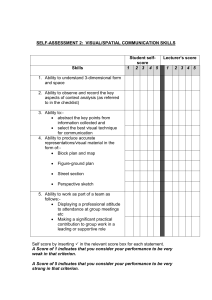

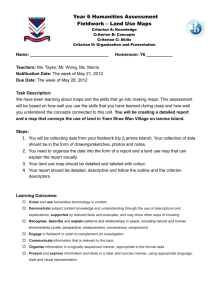

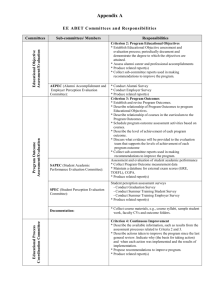

American Economic Association Quasi-Pareto Social Improvements Author(s): Yew-Kwang Ng Source: The American Economic Review, Vol. 74, No. 5 (Dec., 1984), pp. 1033-1050 Published by: American Economic Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/560 . Accessed: 30/01/2015 02:41 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. . American Economic Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The American Economic Review. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 155.69.24.171 on Fri, 30 Jan 2015 02:41:33 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Quasi-Pareto Social Improvements By YEW-KWANG NG* The Pareto criterion is widely accepted as a sufficient condition for an improvement in social welfare. If someone is made better off and no one worse off, there seem to be no acceptable grounds to reject the change. However, most, if not all, changes in the real world involve making some better off and some (no matter how small the number) worse off. Thus the Pareto criterion in itself is of little practical use. On the other hand, the search for a widely acceptable criterion for (social) welfare improvements beyond Pareto, around the 1940's, in the form of compensation tests and the like, seems to have encountered overwhelming objections. As a result, little if any advance has since been made. We still have not gone beyond Pareto as far as a widely acceptable welfare criterion is concerned.' In Section I, I propose a widely acceptable welfare criterion beyond the Pareto principle. The proposal consists in amending the well-known Kaldor-Hicks-Scitovsky double compensation test by requiring it to be satisfied for each and every (usually income) group of individuals. This amendment rids it of its main objection on the ground of distributional considerations (for example, making the poor poorer and the rich much richer is usually not regarded as a good change).2 It may be thought that this amendment is too restrictive and makes the criterion virtually useless. Section II illustrates the wide appli*Reader in Economics, Monash University, Clayton, Victoria, Australia 3168. I am grateful to my colleague Ross Parish for stimulating discussion and to a referee for helpful suggestions. I have also benefited from seminar discussions of earlier versions of Section III at Monash (1976), Virginia Polytechnic Institute, New York, and Yale universities (1978). 'For surveys of the debate on welfare criteria, see Ezra Mishan (1969), John Chipman and James Moore (1978), and my book (1979; 1983, ch. 3). 2Another objection of possible inconsistency after repeated applications is discussed in the Appendix, part A, and regarded as insignificant in practice and hence not a compelling objection to a practical criterion. cability of the criterion by using it to justify a specific proposal for improving the allocation of water. Imperfect knowledge, administrative costs, and the diversity of individual preferences make it impossible, in most cases, to design a change or a policy that makes every individual better off. But it may be possible to design one that makes every group better off, satisfying the criterion. Second, since the criterion is meant as a sufficient, not as a necessary, condition for a social improvement, its acceptance does not prevent one from going beyond the criterion to accept, say, changes that make the poor better off and the rich worse off. Third, when combined with the third-best equality-incentive argument, this criterion leads to a much more forceful principle of a dollar is a dollar irrespective of income groups (Section III). This provides a powerful simplification in economic assessment (of any change, policy, etc.) in general, and in cost-benefit analysis in particular. It provides a formal justification for the separation of equity and efficiency considerations (see Richard Musgrave, 1969; A. C. Harberger, 1971, among others) despite the presence of second-best factors and other complications (Section IV). I. A ProposedWelfareCriterionof Tests Group-SpecificCompensation It is the hypothetical nature of compensation (i.e., without having to execute the actual compensation) that makes compensation tests interesting. With actual compensation to make everyone better off, the change becomes a Pareto improvement and no separate welfare criteria are necessary. But the hypothetical nature also attracts two separate objections. First, both Nicholas Kaldor's criterion (1939; ability of gainers to compensate losers) and John Hicks' criterion (1940; inability of losers to bribe gainers to oppose the change) may be logically inconsistent, since both a change and its reverse 1033 This content downloaded from 155.69.24.171 on Fri, 30 Jan 2015 02:41:33 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 1034 THE AMERICAN ECONOMIC REVIEW (back to the original position) may satisfy the same compensation test. Second, hypothetical compensation need not ensure a social improvement as the smaller amount (in monetary terms) of loss by the losers may be socially more important than the gain to the gainers for some reason. Thus, if the poor lose and the rich gain, the change may not be regarded as an improvement even if it satisfies all compensation tests. Hicks attempts to overcome this second problem by arguing that, with repeated application of compensation tests, " there would be a strong probability that almost all... [individuals] would be better off after the lapse of a sufficient length of time" (1941, p. 111). (See also Harold Hotelling, 1938; James Buchanan and Gordon Tullock, 1962, pp. 77-80; Harvey Leibenstein, 1965.) While this is certainly a very fruitful way of strengthening the compensation principle (as developed further by A. Mitchell Polinsky, 1972), it does not eliminate the problem completely as changes that persistently hurt some particular group cannot be ruled out completely, intertemporal substitution is not perfect, and the aged cannot live much longer. To overcome the two above problems of compensation tests, I propose the following two amendments. The first amendment was made by Tibor Scitovsky (1941). Effectively, a change must satisfy both the Kaldor and the Hicks criteria. Apart from exceptional cases (see my book 1979; 1983, Appendix 4A), little attention has to be paid to this amendment. Especially for changes whose effects are thinly spread across a large number of individuals, the differences between ?CV (the sum of compensating variations in income across individuals) and EEV (sum of equivalent variations) are likely to be small in comparison to the inaccuracies arising from difficulties in data collection. Thus if we are certain that one of the two compensation tests is satisfied, the other is also most certainly satisfied.3 3Due to the fact that CV and EV are measured at given prices while compensation tests are based on feasible compensation which may involve changes in prices, a positive I2CV (2E V) is not necessarily equivalent to the satisfaction of the Kaldor (Hicks) criterion, DECEMBER 1984 The second amendment is concerned with the distributional issue. I. M. D. Little's (1950; 1957) approach was to impose the requirement that any distributional effect must be favorable. This does not free Little's criterion from the charge of logical inconsistency, as it requires only (at least) one of the two compensation tests to be satisfied. I have offered a defense of this aspect of the Little criterion elsewhere (see my book, pp. 68-72; see also Kotaro Suzumura, 1980). Even accepting this defense, the question of how to decide whether the distributional effects are "favorable" is still left unsolved. To make our welfare criterion widely acceptable, the following amendment is proposed. Instead of requiring the satisfaction of compensation tests across all individuals, let us require the same satisfaction within each income group (or other group of the same "deservingness," if income is not the only problem). How finely income groups should be defined is a matter of choice. On one extreme, if all individuals affected by the change fall within the same income group, our criterion is equivalent to the KaldorHicks-Scitovsky criterion. On the other extreme, if an income group is defined narrowly enough such that each individual income-earner is a distinct income "group," our criterion collapses into the Pareto criterion. This latter extreme is unlikely to be relevant in practice for changes that affect a large number of individuals. It is practically impossible to distinguish an income-earner of $23,451 per annum and another of $23,452 per annum. For most practical purposes, the following classification is sufficient: the destitute, the very poor, the poor, the justbelow average, the average, the just-above average, the rather well-to-do (usually called as demonstrated by Robin Boadway (1974). Quoting from my earlier book, "Nevertheless in the real economy where a certain change is small relative to GNP, the payment of compensation is unlikely to change prices significantly. Even if prices are changed, the effects of the changes are likely to be negligible compared with inaccuracies in data collection. Thus, if >CV is big enough to overbalance data inaccuracies, we can be quite safe in concluding that full compensation is possible" (p. 98). See also J. S. Dodgson (1977). This content downloaded from 155.69.24.171 on Fri, 30 Jan 2015 02:41:33 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions VOL. 74 NO. 5 NG: QUASI-PARETO SOCIAL IMPROVEMENTS the middle class?), the very well-to-do (upper middle?) the rich, the very rich, and the extremely rich. Of course, a finer classification may be used with actual income ranges as well as supplementary conditions (number of dependents, etc.) specified if desired. The social marginal utility of a dollar is taken as approximately the same across all income-earners within a given income group. Thus, if compensation is possible within each income class, social welfare may be taken as increased. (For complications arising from a shift in income status from one group into another, see the Appendix, part B). Some people may be willing to go further by allowing net losses in higher income groups provided they are compensated by net gains in lower income groups. I do not propose to strengthen our welfare criterion in this way because: 1) the criterion is meant as a sufficient condition for a social improvement, not a necessary condition; 2) I want to command as wide an acceptance as possible; 3) I have a different method of dealing with the problem of equality (Section III below). It may be thought that, by requiring the satisfaction of the compensation test for each income group, our criterion is very demanding if a fine grouping is adopted such that very few changes can satisfy our criterion. However, this is not the case, rather surprisingly. The next section illustrates how the criterion may be used to sanction certain changes. Section III combines the use of our criterion with the third-best equality-incentive argument to arrive at the powerful conclusion of "a dollar is a dollar" (across all income groups). II. WaterPricing:An IllustrativeApplication of OurWelfareCriterion Water restrictions were introduced in Melbourne in 1982 and continued until now (end of 1983) in a bid to preserve the water supply. It is natural for an economist to ask: why is the price system not used to allocate scarce water? That water is essential for life is not the answer as many other things (food, shelter, clothing, etc.) are also essential. Moreover, a minimum amount (less than 5 1035 percent of present consumption) essential for life can be allowed free and the excess charged according to costs. The cost of charging for water is also not the answer. The "dominant opinion in the field of municipal water supply seems to be that universal metering produces gains that are worth the cost" (Jack Hirshleifer, J. C. de Haven, and J. W. Millman, 1969, p. 45). Moreover, Melbourne already has a metering system with annual reading to charge for possible excess water consumption. The free amount of water consumption (free entitlement) is proportional to the fixed charge which is in turn proportional to the estimated property value. But these free entitlements are such that most households do not have to pay any excess water bill even when consuming as much water as desired. Thus, the bulk costs (metering) of charging for water are incurred without gaining the bulk benefit (incentive to conserve water in accordance to its marginal cost by the majority of consumers)-a most uneconomical situation. My suggestion for changing the present system into a full pricing system (drastically lowering the free entitlements) was referred by the Water Supply Minister to the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works (MMBW) for consideration. After a discussion with the Director of Finance of MMBW, I understand that one of the most important factors they are concerned with is the implication of the proposal on the cross subsidization in the present system. This cross subsidization exists because consumers of high property values are paying high fixed charges. Though they are entitled to proportionately more free water, they seldom use the maximum free entitlements. The situation is more or less as depicted in Figure 1. On average, consumers with property values higher than P consume less than their free entitlements. Those consuming much less than their free entitlements are thus effectively subsidizing those consuming more or only slightly less than their free entitlements (excess water consumption is charged at the same rate as used in the calculation of the free entitlement allowed by the fixed charge). If the free entitlement and fixed charges are reduced proportionately, those presently This content downloaded from 155.69.24.171 on Fri, 30 Jan 2015 02:41:33 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 1036 THE AMERICAN ECONOMIC REVIEW DECEMBER 1984 case. In the proposed system, his free entitlement is reduced to P1D. If he still consumes the average amount P1B, he has to pay BD for excess water consumption (the unit price Proposed fixed charge is kept unchanged). But his fixed charge is reduced by the same amount AC (= BD by Existing average construction). Hence he will be no better off f < consumption B, and no worse off if he continues to consume the same amount P1B. However, he is now I free ~~~~~~~~~~Proposed I ~ entitlement given the opportunity to reduce his water bill by consuming less water. Thus, for the average consumer (those who consume the averpPi age amount at their property values), no is made worse off and most conconsumer FIGURE 1 sumers are made better off by having the opportunity to reduce their water bill. The total revenue to MMBW would be unconsuming much less than their free entitlechanged if consumers did not take up this ments (mainly those with high property valopportunity to save by conserving water. If ues) will gain. Moreover, the per unit price they did save, the amount of water conserved for excess water may have to increase to would be worth the reduced revenue colcompensate for the loss of fixed charges. lected, assuming that the unit price is origiThus those presently consuming more than nally fixed at an appropriate level. their free entitlements (mainly those with low Even ignoring problems of costs of changproperty values) may lose. (Only "may," not ing to the new system, possible difficulties " will," since all consumers gain from the associated with making the cross subsidizamore efficient system and freedom from arbition more transparent, etc., the above protrary water restrictions.) Thus, unless the posed change does not satisfy the Pareto present cross subsidization is regarded as criterion. This is so because not all conundesirable in some sense, the change is not sumers are average consumers. For example, necessarily desirable despite the pure efconsumers with properties valued at Pl may ficiency gain. However, we may devise a consume more or less than P1B (the average system to capture the efficiency gain without figure for these consumers). With the new (on average) changing the cross subsidizasystem, those consuming less than the avertion. This can be done by reducing the fixed age will gain (on top of the opportunity to charges by proportionately less than the resave water) since their fixed charges will be duction in free entitlements for consumers reduced by the amount AC and their excess with high property values. water bills, even if they continue to consume As illustrated in Figure 1, for example, the the same amounts of water, will be only, say, free entitlements can be reduced to a fraction DE. Conversely, those consuming more than of the existing average consumption and the the average will lose (ignoring the gain from fixed charges are adjusted accordingly such the opportunity to save water). Thus, some that any consumer who consumes the old consumers will be made better off and some average consumption at his property value may be made worse off. The Pareto criterion will pay the same total amount (fixed charge is insufficient to sanction the proposed plus excess water bill) as in the present syschange. However, at each property value, tem. For example, a consumer whose propignoring the efficiency gain, the loss of some erty is valued at P' is paying under the consumers is exactly offset by the gain of present system a fixed charge of P'A which others. We may thus expect that our double also measures his free entitlement. If he concompensation test will be satisfied for each sumes the average amount of water P1B, he group of consumers (one at each property pays no excess water bill, as is typically the Existing fixed charge and free entitlement Property value This content downloaded from 155.69.24.171 on Fri, 30 Jan 2015 02:41:33 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions VOL. 74 NO. 5 NG: QUASI-PA RETO SOCIAL IMPROVEMENTS value) when the efficiency gain is taken into account.4 Since the proposed change is unlikely to affect any consumer so severely as to change his status in the income grouping by more than one step (for complications due to such changes, see the Appendix, part B), and since consumers of the same property value may be taken as approximately similar in terms of the rich-poor scale, our welfare criterion is satisfied by the proposed change discussed above. The principle illustrated in the application of this welfare criterion has wide applicability. Most changes affect different individuals differently- some gain, some lose. Even if a change is carefully designed so as to leave some net gain to every group, some nonaverage individuals may still lose. The existence of administrative costs, the lack of perfect information, and/or the principle of equal treatment for equals (consumers of the same property value in the example above) preclude in most cases the possibility of designing a change that will make every individual better off. The use of our welfare criterion thus provides an acceptable middle ground between the Pareto criterion that is almost never satisfied and the ordinary compensation principle that may make a whole group of individuals (for example, the poor) significantly worse off. III. A Dollaris a DollarIrrespective of IncomeGroup Ignoring the differences between EV and CV as insignificant and/or largely offsetting for most changes (at least those with their effects thinly spread; for a way to handle exceptions, see my book, Appendix 4A), and ignoring the effects on relative prices as again insignificant and/or largely offsetting (see my book, p. 98), we may regard the criteria 4Since the change is unlikely to affect prices by a significant extent, we may expect that >2CV> 0, >2EV> 0, and that both the Kaldor and Hicks compensation tests will be satisfied for each group of consumers, assuming no noneconomic objection to the new system as such. 1037 of ECV, EEV, and the Kaldor and Hicks compensation tests as approximately equivalent. These criteria treat a dollar (gain or loss) as equal to another dollar, to whomsoever it goes, the rich or the poor. The main objection to such a principle of "a dollar is a dollar" is the question of inequality in income distribution since many people regard a dollar to the poor as satisfying more important needs than a dollar to the rich, and believe that the relevant benefits or costs should thus be valued accordingly in the application of a welfare criterion or in costbenefit analysis. In particular, differential income (or distributional) weighting and other preferential treatment between the rich and the poor, as well as nonmarket allocation (for example, time limits on metered parking irrespective of willingness to pay) are regarded as desirable despite their efficiency loss. These will be referred to as purely equality-oriented preferential policies. Using our welfare criterion of group-specific compensation tests, I show in this section that the objective of income equality can be better achieved through income taxation. By thus supporting the principle of a dollar is a dollar, I make, somewhat paradoxically, my own welfare criterion redundant. In other words, after justifying a dollar is a dollar, the group-specific proviso in compensation tests need no longer be insisted on. (This paradox is explained in Section V.) Essentially, the objective of achieving a more equal distribution of income is better achieved through income taxation even if disincentive effects are involved since purely equality-oriented preferential policies have efficiency costs5 as well as disincentive effects. A rational individual without money illusion will not only take into account the amount of income earned, but also what he will get from the income. If having a higher income does not enable one to buy more parking space but rather means that one has to pay more for the same thing, and/or means that 50n the potential enormous efficiency costs of the application of distributional weights, see Harberger (1978). This content downloaded from 155.69.24.171 on Fri, 30 Jan 2015 02:41:33 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 1038 THE AMERICAN ECONOMIC REVIEW projects in his favor are less likely to be undertaken, then the extra income will be worth less than it otherwise would be. It is as though the income tax rate has increased. The same degree of disincentive will apply in both cases unless income is valued not so much for its purchasing power but mainly as a status symbol. However, among those people for whom status considerations are important, it is more likely that the pre-tax rather than the post-tax income will be used as an indication. Hence the same degree of incentive still applies. In an ideal first-best world where costless and neutral lump sum transfers (fixed according to potential rather than actual income) are feasible, it can easily be seen that a dollar is a dollar. A dollar must be treated as a dollar to maximize efficiency, and any desired level of equality can be achieved by lump sum transfers. But the real world is not first best as lump sum taxes on potential incomes are not feasible. Actual redistributive policies may take the form of (i) measures that improve both efficiency and equality such as the dismantling of artificial barriers to the equality of opportunity, (ii) progressive income taxation, and (iii) purely equality-oriented preferential policies. Ideally, of course, all of type (i) measures should be adopted. But usually, after all feasible measures of that type have been used, equality is still not regarded as sufficiently attained. Hence, both types (ii) and (iii) are also used. The inferiority of the purely equality-oriented preferential policies may be gauged by the following proposition. PROPOSITION 1: For any alternative (designated A) using a system (designated a) of purely equality-orientedpreferential treatment between the rich and the poor, there exists another alternative, B, which does not use preferential treatment, that makes no one worse off, achieves the same degree of equality (of real income, or utility) and raises more government revenue, which could be used to make everyone better off. Note that this proposition is applicable even in the case where the preferential treatment just happens to be consistent with sec- DECEMBER 1984 ond-best efficiency considerations. Because, alternative B, which does not incorporate purely equality-oriented preferential policies, but, instead, uses system b, designed for efficiency purposes only, would already, within that system b, incorporate the second-best efficiency considerations with which system a just happens to be consistent. In other words, the principle of a dollar is a dollar does not preclude adjustments based on some efficiency considerations such as externalities, second best, etc. But it excludes the purely equality-oriented policies used in practice. However, the existence of alternative B does not necessarily mean that it can be identified and implemented. If system a is designed to take account of second-best considerations, then system b can also be so designed. But system a may only be consistent with second-best considerations by chance rather than by design. In addition, the informational costs of designing a system consistent with the second-best considerations may be prohibitive.6 Then we may not be able to identify system b. Thus, while alternative B may exist, it may not be feasible to implement. Thus, if we wish to strengthen Proposition 1 to be one about the existence of a feasible superior alternative B, it would apply only in a probabilistic sense. That it (the strengthened proposition) still applies in a probabilistic sense is due to the theory of third best. Just as it may be consistent with second-best considerations, system a may also be opposite to the requirement of second best. The theory of third best (see my 1977 article) can then be used to show that -the expected gain is negative. Hence, as far as the second-best consideration is concerned, the use of system a involves negative expected gains. For simplic- 6Second-best taxation-pricing rules are typically very complicated, even if only the efficiency consideration is taken into account. For the current literature on optimal taxation, see James Mirrlees (1976, 1981); Agnar Sandmo (1976). Conditions making second-best considerations ineffective are rather stringent, for example, separability in the utility function (see Anthony Atkinson and Joseph Stiglitz, 1976; compare Theodore Bergstrom and Richard Cornes, 1983). This content downloaded from 155.69.24.171 on Fri, 30 Jan 2015 02:41:33 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions VOL. 74 NO. 5 1039 NG: QUASI-PARETO SOCIA L IMPROVEMENTS ity, we may thus assume that system a is neutral with respect to second-best considerations. (This, in fact, gives it an advantage.) Proposition 1 is established in the Appendix, part C, under the usual assumption that individuals have identical preferences but different abilities. Since preferences do differ in practice, it may thus not be actually possible to make a Pareto improvement upon a system using purely equality-oriented preferential policies. We would then have to work with average individuals and construct an alternative that makes these average individuals (one at each income level) better off. Some nonaverage individuals would be made better off and some worse off. In principle, compensation may be effected to make no one worse off. But this is not practicable. However, while not all individuals can be made better off in practice, each income group could be made better off in the sense that overcompensation is hypothetically possible at each income group. Thus, while the Pareto criterion is not satisfied by the change, my welfare criterion of group-specific compensation test is. Thus this welfare criterion, when combined with the third-best equalityincentive argument, leads to the conclusion of a dollar is a dollar. In itself, my argument does not preclude the joint treatment of equity and efficiency issues due to the second-best consideration (for example, see Dieter Bbs, 1984). But such a sophisticated optimization procedure usually involves prohibitive informational and administrative costs (see my 1977 article), and is also probably politically infeasible as it may involve prices, taxes, etc. favoring the rich and against the poor in some (probably half of all) sectors. As far as I know, all preferential policies in the real world are purely equality oriented. In combination with this practical consideration, my. argument also justifies the complete separation of equity and efficiency considerations. Let us illustrate the argument with a utility possibility map. In Figure 2, Up and UR represent the levels of utility of two (groups of) individuals in the society. Starting from the initial position D on the utility possibility curve I, consider a project (or any change) that involves a negative aggregate net benefit H* \I, \w . \' \ p ~~~~~~~~UP 2 FIGUREi (the possibility curve moves inward to II), and a more equal distribution at point F. If the welfare contour7 W through F passes above D, it appears that the change is desirable. Income weighting in cost-benefit analysis that sanctions such changes seems justified. However, to achieve the degree of equality represented by point F, it would be better to do so by income taxation, travelling along curve I from D to E. It is true that income taxation has disincentive effects and thus the point E is not sustainable. The disincentive effect will lead to a contraction of the utility possibility curve I inwards (not drawn) to pass through, say, point G. In other words, we cannot in fact travel along the utility possibility curve I, but have to travel along the utility feasibility curve I' in redistribution through income taxation. As drawn, G is inferior to F. But what is not commonly recognized is that point F is also not sustainable. If redistribution through income taxation from D to E will lead to the 7Murray Kemp and 1 (1976, 1977, 1982) show that a Bergson-Samuelson social welfare function (SWF) that is Paretian and based only on individual ordinal preferences does not exist for any given fixed set of individual preferences drawn from a wide domain. But we need not confine ourselves to ordinal preferences. In fact, I have shown elsewhere (1975) that a SWF must be an unweighted sum of individual cardinal utilities, if certain reasonable premises are accepted. This content downloaded from 155.69.24.171 on Fri, 30 Jan 2015 02:41:33 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 1040 THE AMERICAN ECONOMIC REVIEW contraction of the utility possibility curve, so will redistribution through cost-benefit weighting from D to F. Abstracting from second-best considerations, II will contract by a roughly similar extent as I does. Hence, instead of point F, we will end up with H which is inferior to G. In the presence of second-best factors, we are uncertain as to which point we will end up with, but the expected average is somewhat below point H. IV. Some Complications In this section, I discuss factors that may render my general argument for a dollar is a dollar in Section III inapplicable. I show that while these considerations qualify my conclusion, the main thrust of the central argument is not much affected. A. Political Constraintson RedistributionthroughTaxation It is argued above that, instead of using weighting, quotas, or other kinds of preferential treatment to achieve the objective of equality (not as second-best correctives), it is better to adopt a more progressive income tax schedule. What if the taxation system cannot be changed to the desired structure due to political constraints? If it is true that we can't change the taxation system but we can effect redistribution by other means, my conclusion may have to be qualified accordingly, though there is still the ethical question of the desirability of doing good by stealth. Yet, why should the political constraint act only to prevent redistribution though taxation and not redistribution by other means? Maybe because the voters are rather irrational. I suspect, however, that on this issue, voters are very rational and practical. The upper and middle ciasses will not only vote a government out of office for carrying out drastic changes in taxation but also for carrying out other drastic redistributive measures. Especially in the long run, the forces that operate to prevent redistribution through taxation will also operate to prevent redistribution by other means. If we are thinking in terms of a distributional equi- DECEMBER 1984 librium, the distribution should be considered not in terms of money income but in terms of real income. Naturally, if the rich are penalized in other ways they will have less tolerance as regards the progressiveness of taxation. For example, had Australia been operating closer to the principle of a dollar is a dollar in the past, the reduction in the progressiveness of its income tax schedule undertaken in 1978 would probably not have been required. Both the rich and the poor would probably have been better off. It is true that actual political decisions are affected by a host of factors and not just by an impartial consideration of a balance between equality and efficiency. However, equality and efficiency are important considerations and the fact that preferential treatment is an inefficient tool to achieve equality and efficiency has to be pointed out. B. TransactionCosts My analysis has been based on the assumption that the additional transaction costs associated with redistribution through more progressive income taxation are not higher than the transaction costs of its alternatives. Apart from the disincentive effect (which has been taken into account and is not subsumed under transaction costs), the costs associated with income taxation seem to fall mainly under 1) costs of administration on the parts of both the taxpayers and the collectors, 2) costs involved in tax evasion and enforcement, and 3) costs of tax lobby activities and the like. It is recognized that all of these forms of costs are substantial. But the relevant amounts are not total costs, only marginal costs. For good or for bad, income taxation will be with us in the foreseeable future. The incremental costs of administration of a more progressive tax system seem trivial. The costs of a change from one system to another may not be trivial, but will probably not be substantial. However, at least in the long run, the relevant comparison is the cost of administering two alternative systems, the difference between which is probably quite negligible. A more progressive tax system may however involve higher costs in encouraging more evasion and more This content downloaded from 155.69.24.171 on Fri, 30 Jan 2015 02:41:33 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions VOL. 74 NO. 5 NG: QUASI-PARETO SOCIAL IMPROVEMENTS lobby activities. But the increase in progressiveness is in lieu of some system of preferential treatment which itself is a subject of evasion and lobbying. While this is a subject where a precise conclusion can hardly be expected, it does not seem probable that costs involved in the latter (i.e., preferential treatment) will be much lower than costs involved in the former (i.e., a more progressive tax system). On the other hand, the costs of administering a pure taxation system are almost certainly significantly lower than those of administering a system of taxation combined with preferential treatment in government expenditure. Hence, consideration of transaction costs seems to strengthen, not weaken, my central conclusion. There may be specific cases whereby the use of an apparently "preferential" policy may be superior to making the income tax more progressive because of significantly lower transaction (evasion, lobbying, and administrative) costs of the former. But such a policy is justified on its efficiency consideration of lower transaction costs (relative to income taxation) and cannot be justified on the purely equality consideration advanced by egalitarian lobbyists. C. Ignorance of Benefit Distribution My argument is based on the assumption that individuals know the distribution of costs and benefits in government expenditure across income groups, or the details of preferential treatment, so that the incentives are the same as an equivalent pure income taxation system. In practice, this knowledge is unlikely to be perfect. On the other hand, most individuals do know the scale of income taxation. Does this asymmetrical knowledge mean that the disincentive effects of income taxation are more severQthan an equivalent preferential expenditure system, as, in effect, argued by Martin Feldstein (1974, p. 152)? In the absence of perfect knowledge, an individual has to base his choice on his estimates. From the fraction of knowledge he possesses, it seems that he is as likely to overestimate as to underestimate the degree of progressiveness implied in a given pref- 1041 erential expenditure system, depending on the psychology of the individual in question. Hence, on the whole, the degree of incentives is likely to be similar between the preferential expenditure system and the pure income taxation system. D. RedistributiveEffects of the Project Itself I have argued that a dollar should be treated as a dollar irrespective of whether it accrues to the poor or to the rich. But this argument does not show that a billion dollars is always equal to a billion dollars. This point can be seen clearly by considering a simple example. Consider two alternative projects: project M will increase the incomes (after allowing for cost share) of one million individuals by $10 thousand each, and project N will increase the income of one single random individual by $10 billion. Ruling out costless lump sum transfers (that would make us indifferent between the two projects), it is clear that project M will be preferred to project N by all social welfare functions egalitarian in incomes. This preference is not based on valuing a marginal dollar to the rich as lower than a marginal dollar to the poor. Rather, it is based on treating the first dollar as more valuable than the 10 billionth dollar, whomever they go to. (Due to diminishing marginal utility or risk aversion, the same person typically regards the loss of $10 thousand as more significant in utility terms than the gain of $10 thousand, and the gain of $10 billion as less than a million times the gain of $10 thousand.) Hence, the equality-incentive argument I use above does not apply here. However, the equality-incentive argument can be used to dispel the possible belief that, since a project that itself creates inequality is inferior to one with the same aggregate net benefits but which does not create inequality, a project that creates equality must be preferable to one with the same aggregate net benefit but distributionally neutral. Consider a third project 0 that will yield the same aggregate net benefits of $10 billion but be distributed across the economy in such a way that the poor will have much higher benefits and the rich have This content downloaded from 155.69.24.171 on Fri, 30 Jan 2015 02:41:33 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 1042 THE AMERICAN ECONOMIC REVIEW DECEMBER 1984 negative benefits. While this may seem to be a good thing in itself, the incentive argument will show that project 0 is in fact inferior to project M. If project 0 were to happen as a natural event, it would be preferable. But if it is chosen instead of project M, it will produce disincentive effects. From the above, it may be said that, for projects whose redistributive effects are marginal, one can simply choose in terms of aggregate net benefits; for projects whose redistributive effects are significant, we should prefer the one with less redistributive effects, given the same aggregate net benefits. This seems to lend support to the concept of a conservative social welfare function discussed by W. M. Corden (1974, p. 107). may be in very short supply. In principle, we could impose appropriately higher taxes on the rich and those who happen to own the goods in short supply and pay subsidies to the poor and the victims of the disaster. Then the policy of a dollar is a dollar could still be best. However, due to time lags, imperfect information, and the like, it may be practically infeasible to effect the required changes in taxes/subsidies in time. Rationing of basic necessities such as medical supplies (which also involves external economies) may then be the best practical solution. However, the possible desirability of violating the principle of a dollar is a dollar in such emergencies does not mean that the same is true for normal times. E. Preferencefor Working G. Nonincome Indices for Preferential Treatment If an individual prefers to have his income by earning it instead of receiving it as a transfer welfare payment, then a cost-benefit analysis that does not take this preference into account may be misleading. This has been emphasized by M. L. Skolnik (1970). This kind of complication can be taken care of by appropriate shadow pricing. For example, in the particular case considered here, the main difference is the possible preference of an individual for earning his income instead of receiving some kind of dole money. This can largely be taken care of by putting an appropriate shadow price on employment. For a single person without dependents, his income from a low-paid job is likely to be sufficient to preclude him from receiving a subsidy. All that is needed is a low or zero income tax, so he will not have to suffer the feeling of being.on the dole. For families with dependents, the subsidy can be effected in the form of, say, substantial child-endowment payments differentiated according to income levels. A fixed child-endowment is used in Australia with no one feeling ashamed of receiving it and the introduction of differentiation is unlikely to change this substantially. F. UnexpectedEmergencies In times of unexpected emergencies such as earthquakes, wars, etc., certain necessities My analysis concentrates on the use of income as the index for preferential treatment and redistributive taxation. But surely income is an imperfect measure of "deservingness," and nonincome variables such as health and age status are likely to enter distributional objectives. In particular, the use of age as an index for preferential treatment will create few, if any, disincentive effects, since one cannot change one's age. However, we can similarly use age as an index for the purpose of tax-subsidy. The purpose of giving assistance to the aged, for example, can be achieved without the additional efficiency costs of, say, giving free milk as some may not wish to drink milk. (Subsidized milk to schoolchildren may, however, be justified on the efficiency ground of merit wants; on merit wants as a possible efficiency ground, see my book, Section 1OA.3). The consideration of nonincome factors does suggest that a single tax based on incomes only may not be sufficient; the tax-subsidy system may have to take nonincome factors into account.8 8 For example, consider the argument of William Baumol and Dietrich Fischer (1979) that the use of discrimination in wage rate is much more efficient (less output foregone) than nondiscriminatory taxation in achieving equality. This is based on the detailed knowl- This content downloaded from 155.69.24.171 on Fri, 30 Jan 2015 02:41:33 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions VOL. 74 NO. 5 NG: QUASI-PA RETO SOCIAL IMPRO VEMENTS A related problem of using income as the basis for taxation is that measured income may be a poor indicator of actual earning potential due to savings, risk bearing, etc. Thus, persons of the same earning potential may be taxed more if they are more willing to bear risk, to save, etc. However, this imperfection applies also to the use of measured income for the purpose of preferential treatment and hence does not affect my argument. In general, to the extent that a better index is available for use as a basis of preferential treatment, it can also be used for the tax-subsidy purpose. Unless there are asymmetrical transaction costs (see Part B above), no qualification to my central argument is necessary. From the discussion above, it may be concluded that none of the complications seem to change my central argument significantly. V. ConcludingRemarks Changes satisfying my proposed welfare criterion may be called quasi-Pareto social improvements as all relevant (usually income) groups of individuals are made better off in the sense of fulfilling the KaldorHicks-Scitovsky double compensation test within each group. It is also only quasi Pareto in the sense that repeated applications of the Kaldor-Hicks-Scitovsky criterion may lead to cyclicity and Pareto inferiority (Appendix, part A). This is due to the necessary approximate nature of all objective measures of subjective welfare changes. But the discrepancies are likely to be overwhelmed by inaccuracies in data collection for changes with effects thinly spread across a large number of individuals. If we are quite certain of edge of individual input supply functions that they recognize to be not available. But they suggest that some rough discrimination between broad groups of income earners such as doctors vs. ditch diggers may yet be feasible. But if such a discrimination of supplementing "wage rates for the one and limit[ing] wages for the other" (p. 522) is feasible, there is little reason to expect that it is not feasible to have higher income tax rates for doctors and lower for ditch diggers. 1043 the fulfillment of our criterion despite data inaccuracies, Pareto inferiority and inconsistency will almost certainly be absent. One or two possible exceptions may be regarded as an unavoidable cost of using a generally good rule in practice (Appendix, part A). When combined with the third-best equality-incentive argument, my criterion leads to the forceful conclusion of a dollar is a dollar irrespective of income groups. This conclusion seems to make the criterion itself redundant. The apparent paradox is easily explained. A dollar is a dollar is evaluated prior to disincentive effects while my welfare criterion is applied to the final outcome inclusive of any disincentive effects. But the principle of a dollar is a dollar does provide a powerful simplification in economic assessment of any policy, change, etc. in general, and in cost-benefit analysis in particular. We may assess on pure efficiency considerations unless certain specific preferential policies may be justified on grounds of asymmetrical transaction costs or asymmetrical political feasibility, or the like (Section IV). Pure equality considerations do not provide adequate justification for preferential treatment between the rich and the poor, or for a departure from a dollar is a dollar. Consider again the water pricing example of Section II. Unless some specific argument (on top of equality) can be advanced for cross subsidization, it is better to go further than the proposal of Section II which maintains the present cross subsidization. It is better to have a straight dollar-for-dollar pricing system without cross subsidization. One possible argument for cross subsidization is the infeasibility of making the income tax system more progressive to compensate for the withdrawal of cross subsidization. This is quite likely true in the short run, but not in the long run (Section IV). Another possible argument is that it may be more difficult to avoid paying the cross subsidies attached to properties than to avoid paying income taxes. If this is true, it is still better to have a property tax than attaching the tax to unused water entitlements with the efficiency loss of discouraging water conservation. If this is politically infeasible for some reason, the proposal of Section II based on my welfare criterion may then be considered. This content downloaded from 155.69.24.171 on Fri, 30 Jan 2015 02:41:33 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions DECEMBER 1984 THE AMERICAN ECONOMIC RE VIEW 1044 APPENDIX uK A. The Acceptabilityof the Kaldor-Hicks-ScitovskyCriterionin the Absence of Distributional Considerations Here I provide an argument in favor of accepting the Kaldor-Hicks-Scitovsky criterion, in the absence of distributional consideration, as a practical criterion for general economic application, despite the acknowledged possibility of cyclicity after repeated usage. Even abstracting away distributional considerations (or other grounds for differentiating "deservingness"), the Kaldor-HicksScitovsky criterion (which requires the satisfaction of both the Kaldor and Hicks compensation tests) is not an ideal sufficient condition for a social improvement. This is so since a logical contradiction is possible after repeated applications of the criterion (W. M. Gorman, 1955; John Chipman and James Moore, Section 3; my book, p. 66). As illustrated in the utility space of Figure 3 (where the curves are utility possibility curves), the changes from ql to q2, q2 to q3, q3 to q4, and q4 back to ql all satisfy the criterion. Moreover, q4 is in fact Pareto inferior to ql. Thus the criterion is not only logically inconsistent, but can lead to a Pareto-inferior situation. The possible cyclicity and Pareto inconsistency of the Kaldor-Hicks-Scitovsky criterion illustrates the difficulty of making social welfare judgments without interpersonal comparison of individual cardinal utilities. In fact, I have established elsewhere (1982, Proposition 4) that, given a sufficiently wide domain (a condition less demanding than Universal Domain and satisfying conventional "economic" assumptions of self interest, nonsatiation, etc.), there exists no non-cardinalistic ranking rule yielding consistent ordering of social states satisfying anonymity and the Pareto principle. A noncardinalistic ranking rule is a rule specifying social ranking of pairs of social states based on individual rankings (but not on preference intensities) of the respective pairs and (possibly) on some (but not all) objective characteristics of the social states. The 44 q , u 0 FIGURE 3 Kaldor-Hicks-Scitovsky criterion is in fact more than a non-cardinalistic ranking rule as it effectively uses the amount of compensation required and the willingness to pay as indirect measures of subjective preference intensities. But since these indirect measures are not perfect in their correspondence with subjective preferences, inconsistencies may arise. This difficulty is present for all nonsubjective measures of welfare. Since the relation between units of any external yardstick of welfare such as money and internal (subjective) units of welfare is in general not a constant (making intersections of utility possibility curves as in Figure 3 possible), such objective measures can be, by their very nature, no more than an approximate measure of welfare, even abstracting from the problem of inaccuracies in practical data collection. If we recognize the necessity for this approximate nature, the possibility of inconsistency (as well as such problems as path-dependency in consumers' surplus measurement) becomes acceptable unless the discrepancies involved are substantial and frequent. For general application in judging the desirability of economic policies with widely and thinly spread costs and benefits, the discrepancies involved are likely to be small and largely offsetting to each other. Thus, if the satisfaction of the Kaldor-Hicks- This content downloaded from 155.69.24.171 on Fri, 30 Jan 2015 02:41:33 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions VOL. 74 NO. 5 NG: QUASI-PARETO SOCIAL IMPROVEMENTS Scitovsky criterion is fairly certain despite inaccuracies in data collection, we can be quite sure that the problem created by the approximate nature of our measurement will be overwhelmed. One or two odd cases of inconsistencies may still remain, but that can be regarded as an unavoidable cost of using a generally desirable rule. For example, the rule that motorists must stop at red traffic lights is certainly desirable as it prevents accidents and congestion, but it also creates some unnecessary waiting time. It is Pareto inferior for someone to wait for a green light when no one is crossing the intersection from any direction. But it is impractical to allow such Pareto improvements of crossing red lights without creating dangerous accidents. Similarly, before it is practicable to use some direct measurement of subjective welfares,9 we have to make do with imperfect substitutes usually in some form of willingness to pay. Recognizing the necessary approximate nature of such measures, the possibility of inconsistency is not a compelling objection. The use of the Kaldor-Hicks-Scitovsky criterion, when distributional considerations have been dealt with as suggested in Section I, can thus be justified. B. Dealing with Changes in Income-GroupStatus In Section I, a welfare criterion (or a sufficient condition for a social improvement) is proposed that requires the satisfaction of the Kaldor-Hicks-Scitovsky (double) compensation test for each income group. A problem arises when some persons in an income group are made so much better off or worse off as to change their status into different income groups. For example, if a change affects the income levels of the poor by making most of the poor poorer and making a few rich such that compensation is possible, one may not wish to regard such a change as socially desirable. My compensation test will work 9Such as the psychological measurement based on just noticeable differences; see my article (1975) on such a measurement and ways to overcome practical difficulties. 1045 best if no such changes of income status take place. But since a person on the top (bottom) of an income group need only to be made a little richer (poorer) to change his status, a change in status by not more than one step may be regarded as acceptable such that he can be included in his original income group for the purpose of compensation test. If the social marginal utility of a dollar is regarded as approximately equal for all individuals in the same income group, they do not differ by too much for neighboring income groups. For persons who jump income groups by more than one step, the following method of using my compensation test is suggested. One who jumps up the scale from income group G to G + A, where A is a positive integer larger than one, may be included in his original income group (G) for testing compensation provided his gain is (hypothetically) reduced to an amount making him no higher than the top of the income group G + 1. In other words, his gain in income above this amount is disregarded for the purpose of the compensation test. To be conservative, we may insist that no one be made to jump down the income groups by more than one step. Alternatively, we may require that if such a downward jumping occurs, the person involved should be included in his new income group for the purpose of the compensation test. If we adopt the latter alternative, it is consistent to allow the following. For a person who jumps upward by more than one step, if his original income group already satisfies the compensation test without including him, his gain may be included, if needed, in the compensation test of the income group he moves into. C. A Dollar is a Dollar: Proof of Proposition1 To establish Proposition 1 in Section III, let us adopt the following simplifying assumptions: 1) there is no political constraint on redistribution through taxation; 2) the administrative costs of the pure taxation system are no higher than its alternative, for any same degree of equality attained; 3) all individuals know the relevant taxation scale, details of government expenditure, etc.; 4) This content downloaded from 155.69.24.171 on Fri, 30 Jan 2015 02:41:33 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions THE AMERICAN ECONOMIC RE VIEW 1046 DECEMBER 1984 Post-tax D income I; <13>:~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ E, _ _ _ __ _ _ _ I 0 CI _ __ _ _ __ _ _ _ _I__ _ P re-ta x ____ C2 C3 income FIGURE 4 there are no money illusion or similar "irrational" preferences. In Section IV, we see that the relaxation of these assumptions does not affect the argument significantly. Let us define a system of perfect preferential treatment as one that involves a degree of preferential treatment that is monotonically decreasing in incomes. Initially, I shall establish the proposition by assuming, first, that system a is perfect, and second, that individuals have the same utility function between income and leisure (but may have different earning abilities). Consider Figure 4 where curve a represents a given income tax schedule relating post-tax to pre-tax income levels. For example, a person earning OC3(= C3D) will be taxed DE3 and left with E3C3as his post-tax income. Each person has a given incomeearning ability. Subject to this earning ability, each person may choose. different levels of pre-tax income by varying his hours and intensity of work. His choice depends, of course, on his subjective preference (with respect to leisure, consumption, and the preferential system), the tax schedule, and the system of preferential treatment. Let alternative A be the tax schedule a and a given system of preferential treatment a. Even with the assumption that all individuals have the same subjective preference (or utility func- tion), persons of different earning abilities may have different indifference maps as defined on Figure 4. (This is similar to James Mirrlees' model of optimal income taxation. See J. K. Seade, 1977, for a diagrammatical illustration.) Given some mild assumptions, income varies positively and continuously with earning ability (Mirrlees, 1971). Geometrically, a person with higher earning ability has a flatter indifference curve at a given point. This is so since a person of lower earning ability needs to work more to earn a given income. The equilibrium points (E1, E2,E3) of three individuals under alternative A are depicted in Figure 4. Now let us dismantle the system of preferential treatment a. This will make the rich better off and may make the poor worse off. If system a is so inefficient such that its dismantling makes everyone better off, we have a stronger case for its removal. Thus, let us take the case where the poor will be made worse off by its removal. Since the preferential treatment is assumed perfect, there exists an intermediate income level (say C2) at which the individual would stay indifferent by the removal of system a. This individual must exist in a model of a continuous distribution of individuals but may not exist in the discrete case. But the actual existence of this individual is of no consequence to my This content downloaded from 155.69.24.171 on Fri, 30 Jan 2015 02:41:33 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions VOL. 74 NO. 5 1047 NG: Q UASI-PA RETO SOCIA L IMPRO VEMENTS argument. After the removal of system a, the new indifference curve of this individual that corresponds to the same level of utility as I2 must still pass through the point E2. On the other hand, individual 3 who is made better off by the removal of system a, must have a new indifference curve (IE), that corresponds to the same level of utility as I3, passing through a lower point E'. With no preferential treatment against him, he now only needs a lower level of post-tax income to attain the original utility level at the same level (0C3) of pre-tax income.10 Conversely, the new indifference curve (1) for individual 1 passes through a higher point E'. Tracing through all points such as E', E2, E', we arrive at the new tax schedule /8. With the usual continuity assumptions, this schedule will also be continuous and smooth. (Continuity and smoothness are not really necessary for my central proposition but they make the illustration easier and enable it to be put in terms of the familiar tangency condition for maximization.) Let us call the tax schedule /3 with no preferential treatment alternative B. If the government can collect at least as much revenue as before to maintain public expenditure, it is clear that everyone will remain at least as well off as under alternative A. This is so since each person can always choose to earn the same amount of pre-tax income and attain the same level of utility as before. However, if alternative B has greater disincentive effects, many individuals may choose to earn less and government revenue may be smaller than before. Let us examine this possibility. Consider Figure 5 which is an enlargement of the relevant section of Figure 4. If the new indifference curve of individual 2 does not only pass through E2 but also stays un10This is obviously true with the assumption of given earning abilities. With the relaxation of this assumption, it may be thought that I3 may pass above E3 (and I, below El) if the wage rate of individual 3 (individual 1) is sufficiently increased (reduced) by the operation of preferential system a. If this is so, it means that preferential system a in fact favors the rich rather than the poor when its full effects (including the indirect effect on earning abilities) are taken into account. This possibility may thus be disregarded. It is also clear that the indirect effect is unlikely to outweigh the direct effect. Post-tax income o C2 Pre-tax income C2+ FIGuRE 5 changed at I2 (at least in the neighborhood of E2), the new tax schedule ,/, being flatter than a, must cut this indifference curve (I2)' Individual 2 would then choose to earn a lower level of pre-tax income, say, at point F. However, the actual new indifference curve (1) must be flatter than the old one 12 at point E2. With no preferential treatment, he would need less (more) post-tax income if he were to earn a higher (lower) level of pre-tax income. (Otherwise /3 would not be flatter than a to begin with.) Moreover, it can be shown that I' must be tangential to /3 at E2. The tax schedule a touches the (highest) indifference curve I2' Both 12 and a are reduced in slope to become 1 and /3, respectively. Moreover, the reduction in slope must be the same at the point E2. Hence /3touches I' at F2. To see this more clearly, consider a slightly higher level of pre-tax income C2 + ?. The slope of '2 at E2 (denoted S2) may be approximated by GH/E2H. This approximation will become exact equality as we make approach zero, given smoothness in the curve. Similarly, the slope of 1 at E2 (denoted S') = JH/E2H, and the slope of a at E2, S, = KH/E2H, and the slope of /3 at E2, S# = LH/E2H. Since the denominators of all these slopes are the same, we may concentrate on the numerators. Slope S2 is larger than S' by (approximately) GJ, ignoring the denominator. GJ measures the extent to which individual 2 would be made better off This content downloaded from 155.69.24.171 on Fri, 30 Jan 2015 02:41:33 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 1048 THE AMERICAN ECONOMIC RE VIEW by the removal of preferential system a had he chosen to earn C2+ - instead of C2.11 Slope Sa is larger than S8 by KL. Thus KL measures the extent to which the individual who actually earned C2+ - under alternative A would be made better off by the removal of preferential system a if he were to keep earning C2 + e. It must be recognized that GJ need not equal KL. Although the pre-tax (C2 + c) incomes of both individuals are the same if the above hypothetical conditions prevail, they have different earning abilities. The same pre-tax income must then imply different hours or intensities of work. This difference in hours of work may then make them willing to forgo a different sum of post-tax income to remove the same system (and the same degree) of preferential treatment. However, as we make - approach zero, not only do the above approximate measures of slopes become exact, the difference in the earning abilities of the two individuals also approaches zero. Given continuity, the amount by which S2 is larger than S2' will than be equal to the amount by which Sa is larger than S, at point E2 as the measures of these slopes are made exact. Since S2 = Sa at E2, so SS2-= at E2. It is then not difficult to see that, under alternative B, not only can individual 2 attain the same level of utility as before by earning the same income as before, he has no incentive to earn a different income. Given some convexity assumptions, he would be positively worse off if he operated at a different point. Let us now go back to Figure 4 to consider the position of individual 3. Now S3 (slope of I' at E') may differ from S3 for two reasons. One is the same as that which makes S2 differ from S2, that is, the removal of preferential treatment tends to make the slope flatter. But since E3 and E' are now two 1l This is so due to the argument in Section III abstracting away the possible second-best effect of preferential system a. This effect may change the tradeoff between consumption and leisure, i.e., the slopes of indifference curves in the figure. Then GJ may partly reflect this second-best effect. However, this second-best effect may go in either direction and, as argued above, would result in a negative expected gain. Thus, by abstracting away the second-best effect, we in fact give alternative A an advantage. DECEMBER 1984 different points, there is an additional reason for S3 differing from S3. The difference in post-tax income may make the individual have a different tradeoff between consumption (or post-tax income) and leisure (related to pre-tax income). However, SA (at E') also differs from Sa (at E3) for these two reasons. It is thus not difficult to see that S must equal S3' at E3. Individual 3 will choose to earn the same amount of pre-tax income as before. Similar reasoning shows that under alternative B, all individuals will choose to earn the same amounts of pre-tax income as under alternative A. Alternative B thus provides the same degree of incentives and the same degree of equality in the distribution of real income (utility) as alternative A. Even if all individuals earn the same amount of pre-tax income, can we be sure that government revenue is no smaller under alternative B? In Figure 4, let C1 (it could be zero) be the lowest pre-tax income earned and C3 be the highest. The change in government revenue in moving from alternative A to B equals the area E2E3E weighted by population density function along the horizontal axis minus the area E' E1E2, similarly weighted. It is clear that the weighted area F2F3 E' must be larger than the weighted area E'EIE2. The former measures the aggregate amount by which all individuals earning more than C2 are made worse off by preferential system a. The latter area measures the aggregate amount by which all individuals earning less than C2 are made better off by system a. If the former area was smaller than the latter, system a would be justified on pure efficiency grounds to start with. Thus if system a is truly preferential, the former area must be larger than the latter. For example, the use of unequal income weighting in cost-benefit analysis may sanction projects with positive unweighted aggregate net benefits. But such projects will be sanctioned without the use of unequal income weighting and would be undertaken under alternative B, too. Hence the difference in tax schedules a and /3 is caused by the effects of preferential measures such as unequal income weighting when they are effective in sanctioning projects with negative unweighted aggregate net benefits. This content downloaded from 155.69.24.171 on Fri, 30 Jan 2015 02:41:33 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions VOL. 74 NO. S NG: Q UASI-PA RETO SOCIA L IMPRO VEMENTS From the above discussion, it can be seen that alternative B not only provides the same degree of incentives and the same degree of equality in the distribution of real income (utility), it also generates more government revenue than alternative A. This extra amount of revenue is a measure of the superiority of B (no preferential treatment but more progressive income taxation) and can be used to make everyone better off by increasing public expenditure and/or lowering taxes all round. The argument above is based on the assumption of perfect preferential treatment. The degree of preferential treatment is taken to be a monotonically decreasing function of incomes across all individuals. In practice, preferential treatment in government expenditure cannot be perfect. For one thing, some expenditures benefit all people in the same geographical area. The government may choose to spend more on poor areas, but a rich person living in a predominantly poor area will benefit as well. A person is not likely to change his place of residence each time his income is increased. Hence, for any person living in a particular area, he will not be appreciably adversely affected if he earns more by those government expenditures that are geographically specific. The increase in his income does not appreciably increase the average income of the whole area. But for the purpose of income taxation, it is individual income alone that counts and not the average income of the whole area. It follows that the disincentive effect of pure income taxation (alternative B) is greater than that of income taxation with lower progressivity but with imperfect preferential treatment (alternative A'). Does it follow that alternative B is inferior to alternative A'? No, as the following paragraph shows. The reason we have to make do with imperfect preferential treatment is the infeasibility or very high costs of effecting perfect preferential treatment, not that we prefer imperfect preferential treatment (alternative A') to perfect preferential treatment (alternative A) as such. Abstracting from the problems of feasibility and transaction costs, alternative A is preferable to A'. But it has been argued above that alternative B is pref- 1049 erable to alternative A (without counting the transaction costs involved in A). It follows that alternative B must be preferable to A'. This is so despite the fact that the disincentive effect is higher under B. The imperfection of alternative A' involves welfare loss in terms of inequity which must be larger than the costs of higher disincentive effects of B or A (which have the same incentives), otherwise A' would be preferable to A. Thus the problem of imperfection in preferential treatment does not affect my conclusion. REFERENCES Atkinson, Anthony B. and Stiglitz, Joseph E., " The Design of Tax Structure: Direct versus Indirect Taxation," Journal of Public Economics, July-August 1976, 6, 55-75. Baumol, William J. and Fischer,Dietrich,"The Output Distribution Frontier: Alternatives to Income Taxes and Transfers for Strong Equality Goals," American Economic Review, September 1979, 69, 514-25. Bergstrom,TheodoreC. and Cornes,RichardC., " Independence of Allocative Efficiency from Distribution in the Theory of Public Goods," Econometrica, November 1983, 51, 753-66. Boadway,RobinW., "The Welfare Foundation of Cost-Benefit Analysis," Economic Journal, December 1974, 84, 926-39. Bos, Dieter, "Income Taxation, Public Sector Pricing, and Redistribution," typescript, 1984. Buchanan,James M. and Tullock,Gordon,The Calculus of Consent, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1962. Chipman,John S. and Moore, James C., "The New Welfare Economics 1939-1974," International Economic Review, October 1978, 19, 547-84. Corden, W. M., Trade Policy and Economic Welfare, London: Oxford University Press, 1974. Dodgson,J. S., "Consumer Surplus and Compensation Tests," Public Finance, No. 3, 1977, 32, 312-20. Feldstein, Martin S., "Distributional Preferences in Public Expenditure Analysis," in H. M. Hochman and G. E. Patterson, eds., Redistribution ThroughPublic Choice, New This content downloaded from 155.69.24.171 on Fri, 30 Jan 2015 02:41:33 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 1050 THE AMERICAN ECONOMIC REVIEW York: Columbia University Press, 1974. Gorman,W. M., "The Intransitivity of Certain Criteria used in Welfare Economics," Oxford Economic Papers, February 1955, 7, 25-35. Harberger,A. C., "The Three Basic Postulates for Applied Welfare Economics: An Interpretive Essay," Journal of Economic Literature, September 1971, 9, 785-97. _ , "On the Use of Distributional Weights in Social Cost-Benefit Analysis," Journal of Political Economy, April 1978, 86, S87-S120. Hicks, John R., "The Valuation of Social Income," Economica, May 1940, 7, 105-24. ___ "The Rehabilitation of Consumer's Surplus," Review of Economic Studies, February 1941, 8, 108-16. Hirshleifer,Jack, de Haven, J. C. and Millman, J. W., Water Supply: Economic Technology, and Policy, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1960, rev. 1969. Hotelling, Harold, "The General Welfare in Relation to Problems of Taxation and of Railway and Utility Rates," Econometrica, July 1938, 6, 242-69. Kaldor, Nicholas, " Welfare Propositions of Economics and Interpersonal Comparison of Utility," Economic Journal, September 1939, 49, 549-52. Kemp,MurrayC. and Ng, Yew-Kwang,"On the Existence of Social Welfare Functions, Social Orderings and Social Decision Functions," Economica, February 1976, 43, 59-66. , "More on Social Welfare and Functions: The Incompatibility of Individualism and Ordinalism," Economica, February 1977, 44, 89-90. and _ , "The fncompatibility of Individualism and Ordinalism," Mathematical Social Sciences, July 1982, 3, 33-38. Leibenstein, Harvey, "Long-Run Welfare Criteria," in J. Margolis, ed., The Public Economy of Urban Communities, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1965. Little, I. M. D., A Critiqueof WelfareEconomics, London: Oxford University Press, 1950; 1957. DECEMBER 1984 Mirrlees, James A., "An Exploration in the Theory of Optimal Income Taxation," Review of Economic Studies April 1971, 38, 175-208. , " Optimal Tax Theory: A Synthesis," Journal of Public Economics, November 1976, 6, 327-58. ,_ The Theory of Optimal Taxation," in K. J. Arrow and M. D. Intriligator, eds., Handbook of Mathematical Economics, Vol. III, Amsterdam: North-Holland, 1981. Mishan, Ezra J., Welfare Economics: An Assessment, Amsterdam: North-Holland, 1969. Musgrave,RichardA., "Cost-Benefit Analysis and the Theory of Public Finance," Journal of Economic Literature, September 1969, 7, 797-806. Ng, Yew-Kwang,"Bentham or Bergson? Finite Sensibility, Utility Functions, and Social Welfare Functions," Review of Economic Studies, October 1975, 42, 545-70. ,_ "Towards a Theory of Third Best," Public Finance, No. 1, 1977, 32, 1-15. Welfare Economics: Introductionand Development of Basic Concepts, London: Macmillan, 1979; 1983. , "Beyond Pareto Optimality: The Necessity of Interpersonal Cardinal Utilities in Distributional Judgements and Social Choice," Zeitschriftfur Nationalokonomie, November 1982, 42, 207-33. Polinsky, A. Mitchell, "Probabilistic Compensation Criteria," Quarterly Journal of Economics, August 1972, 86, 407-25. Sandmo, Agnar, "Optimal Taxation: An Introduction to the Literature," Journal of Public Economics, June 1976, 6, 37-54. Scitovsky,Tibor,"A Note on Welfare Propositions in Economics," Review of Economic Studies, November 1941, 6, 77-88. Seade, J. K., "On the Shape of Optimal Tax Schedules," Journal of Public Economics, April 1977, 7, 203-35. Skolnik, M. L., "A Comment on Professor Musgrave's Separation of Distribution from Allocation," Journal of Economic Literature, June 1970, 8, 440-42. Suzumura,Kotaro, "On Distributional Value Judgments and Piecemeal Welfare Criteria," Economica, May 1980, 47, 125-39. This content downloaded from 155.69.24.171 on Fri, 30 Jan 2015 02:41:33 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions