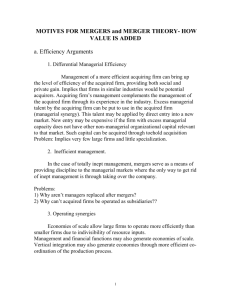

Introduction to Mergers and Acquisitions

advertisement

XV.

INTRODUCTION TO MERGERS AND ACQUISITIONS: FIRM

DIVERSIFICATION

In the introduction to Section VII, it was noted that firms can acquire assets by either

undertaking internally-generated new projects or by acquiring existing assets of other firms.

Having examined the former there and again in Section XIV, we now turn to the latter.

Under the operational criterion for good management of maximizing current shareholders'

wealth, there are essentially three reasons for considering the acquisition of another company:

1.

Synergy: By combining the two companies, the value of the operating assets of the

combined firm will exceed the sum of the values of the operating assets of the two

companies taken separately. Such synergy will occur if there are economies of scale in

marketing, purchasing of materials, plant size, and distribution system. It can also occur

through the elimination of duplicate efforts in management or research and development.

Such economics are most likely to occur with either horizontal or vertical mergers. In

essence, the value goes up because the factors of production are more efficiently

organized in the combined firm.

2.

Taxes: The market value of the firm reflects its value to the private sector. Of course,

since the firm pays taxes (or may pay taxes in the future), there is an additional "shadow"

value of the firm to the public sector in the form of the present value of its tax payments.

The sum of the market value and this "shadow" value is the value of the firm to society.

In the case of synergy, the value of the firm to society is increased with a corresponding

increase in both the market and shadow values of the firm. However, if a combination of

two firms can reduce the combined present values of these firms' tax payments taken

separately, then the market value of the combined firm can exceed the sum of the values

of the two firms taken separately even if the value of the combined firm to society is just

equal to the sum of the values to society of the two firms. I.e., this combination does not

increase the total value to society, but it does redistribute the total between the

287

Robert C. Merton

shareholders of the firms and the public sector. Two examples are: (a) a more-effective

use of a tax-loss carryover; (b) increased debt capacity for the combined firm which may

reduce taxes if there is a "tax-shield" value to the deductibility of interest [see Section IX

for further discussion].

3.

The Firm to be Acquired is a "Bargain": If the firm to be acquired has a market value

which is less than its "fair" value, then by acquiring the firm, the management of the

acquiring firm can increase its stockholders' wealth. There are two distinct reasons why a

firm could be selling for less than "fair" value. The first is that relative to the acquiring

firm's information set, the stock market is not efficient in the sense to be discussed in

Section XVII.

That is, the management of the acquiring firm believes that it has

information such that if this information were widely-known, the market value of the firm

to be acquired would be higher than its acquisition cost. If this is the principal reason for

the acquisition, then the management's behavior is identical to that of a security analyst

whose job it is to identify mispriced securities. In terms of the CAPM and Section XIII,

the management believes it is purchasing a security with a positive "alpha" (α) . Hence,

all the warnings about being able to "beat the market" given in that section apply equally

well here.

A second reason why a firm could be selling for less than its "fair value" is that the firm

to be acquired is currently being mismanaged.

That is, through either incompetence or

malevolence, the current management is not managing the firm's resources so as to maximize the

market value of the firm. Unlike the first reason, this reason is completely consistent with an

efficient capital market. Indeed, as discussed at length in Section III, from society's point of

view, this reason is probably the most important one for permitting mergers and takeovers.

288

Finance Theory

Firm Diversification

Notable by its absence among the three reasons for acquisitions is diversification: That

is, the acquisition of another firm for the sole purpose of reducing the volatility (variance or

"total" riskiness) of the firm's operations. Although "diversification" is a frequently cited reason

for an acquisition, it is often not the "real" reason. More often than not, it will be for one of the

three reasons already given. However, if diversification is the real reason, then the acquisition

route will in general be an inefficient way to achieve it.

The argument for firm diversification is often presented by analogy with an individual

investor where we have seen that diversification is quite important. However, this type of

argument simply illustrates the pitfalls of treating the firm "as if" it were an individual household

with exogenous preferences rather than as an economic organization designed to serve specific

economic functions.

To show why firm diversification is not an important activity for management and if it is

undertaken, why the acquisition route is inefficient, we begin with an explicit analysis of the

value of the firm under the capital asset pricing model. Let there be two firms where each firm

has a single project as described in the beginning of Section XIV. From formula (XIV.2), the

value of firm i (i = 1,2) is given by

(XV.1)

Vi =

Ii

[ x - λ e νi ρiM ], i = 1,2.

R i

Suppose that firms #1 and #2 merge to form firm #3. In an analogous fashion to firms #1 and #2,

define I3 as the investment in firm #3 and ~x 3 as the random variable end-of-period cash flow of

firm #3 per dollar of investment. If no changes in the investment plans of the firms occur as a result of

the

combination,

then

where

x2

I3 ≡ I1 + I2 and ~

x3 ≡ δ ~

x1 + (1 - δ) ~

δ≡

I 1 . 2 ≡ VAR( ) = 2 2 + (1- δ 2 2 + 2δ (1- δ )Cov( , ).

) ν2

ν3

x% 3 δ ν 1

x% 1 x% 2

I 1+ I 2

289

Robert C. Merton

(XV.2)

ρ3M ≡ V

Cov[~

x 3 , ZM ]

ν3 σM

~

δCov[ x1 , ZM] + (1 - δ)Cov[~

x 2 , ZM ]

=

ν3 σ M

δ ν1 σM ρ1M + (1 - δ) ν 2 σM ρ2M

=

ν3 σM

δ ν1 ρ1M + (1 - δ) ν 2 ρ2M

=

ν3

From Section XIV, (XIV.2), the value of firm #3 will satisfy

V3 =

(XV.3)

I3

[ x - λe ν3 ρ3M]

R 3

Substituting into (XV.3) for ρ3M from (XV.2), we have that

V3 =

(XV.4)

I3

{ x - λe [δ ν1 ρ1M + (1 - δ) ν 2 ρ2M]}

R 3

Noting that x ≡ E[~x 3] = δ x1 + (1 - δ) x 2 , we have that

V 3=

(XV.5)

I3

{ δ [ x1 - λ eν 1 ρ 1M ] + (1- δ )[ x 2 - λ eν 2 ρ 2M ]}

R

But I3δ = I1 and I3(1–δ) = I2 . Hence, from (XV.5), we have that

I1

I

[ x1 - λ e ν1 ρ1M ] + 2 [ x 2 - λe ν 2 ρ2m]

R

R

= V1 + V 2 .

V3 =

(XV.6)

Thus, the value of the combined firm will just equal the sum of the values of the two firms prior

to the merger.

In connection with both mergers and firms possibly undertaking many (independent)

capital budgeting projects, we generalize the above demonstration to a firm with m projects.

290

Finance Theory

Let firm P take on m different projects where physical investment in project i is Ii

m

and the random variable end-of-period cash flow is IP = ∑ Ii , and total firm end-of-period cash

i =1

flow per dollar of physical investment x P , can be written as

m

x P = [∑ Ii x i]/ IP

i =1

m

(XV.7)

= ∑ δi x i

i =1

where δ i ≡ I i / I P and

m

∑δ i = 1 .

i=1

It follows from (XV.7) that

m

(XV.8)

x P = ∑ δi x i

i =1

and

(XV.9)

Var( x P ) ≡ ν 2P =

m m

∑∑δ iδ j Cov( xi , x j ) .

i=1 j=1

It follows also that

Cov( x P , ZM ) = ρPM ν P σ M

(XV.10)

m

= ∑ δi ρiM νi σM .

i =1

291

Robert C. Merton

From (XIV.2), (XV.8), and (XV.10), we have that

VP =

IP

[ x - λe ν P ρPM ]

R P

=

m

IP m

[∑ δi x i - λ e ∑ δi νi ρiM ]

R i =1

i =1

=

IP m

[∑ δi ( x i - λe νi ρiM )]

R i =1

=

∑ Vi

(XV.11)

m

i =1

where Vi = Ii ( x i - λe νi ρiM )/R is the "stand-alone" value of project i .

Hence, diversification does nothing to the market values of the firms and hence,

according to the value-maximization criterion, it is not important. The result shown in (XV.6)

and (XV.10) is called value additivity and can be shown to obtain in quite general structures

(provided that there exists a well-functioning capital market).

An intuitive explanation of why the market values are unaffected even though the

combined firm may have a smaller total risk (variance) than the individual firms is as follows: In

order for investors to be willing to pay a higher price for the combined firm than they were

willing to pay for the two firms separately, the act of combining the two firms must provide a

"service" to the investors which they were previously unable to obtain. However, prior to the

combination, any investor could purchase shares of either or both firms in any mix he wants.

And, in particular, in the case of the merger, the investor could purchase the shares of firm #1 to

firm #2 in the ratio V1 / V 2 which is exactly the ratio implicit in the combined firm. Hence, each

investor could achieve for himself (prior to the merger) the same amount of diversification (of the risks

of the firms #1 and #2) as is provided by the combined firm, and therefore, the merger provides no new

diversification opportunities to investors. For that reason, investors would not pay a premium for the

combined firm.

Although it will not be the case for the capital asset pricing model, it is possible that the

combined firm could sell for less than the sum of the values of the two separate firms, i.e., that

firm diversification could "hurt" market value. The reason is that post-consolidation, investors

have fewer choices for portfolio construction than they did pre-consolidation. For example, prior

292

Finance Theory

to the merger, an investor could hold positive amounts of firm #1 and none of firm #2 or vice

versa. Post the merger, the only way that an investor can hold firm #1 is to invest in the

combined firm #3 which means he must also invest in firm #2.

Indeed, he can only invest in firm #1 if he is willing to invest in firm #2 in the relative

proportion V1 / V2 . The reason that this "loss of freedom" does not have a negative effect on the

combined firm's value is the CAPM is that in that model, it is optimal for all investors to hold firm #1 and

firm #2 in the relative proportions V1 / V 2 which is exactly the proportion provided by the combined

firm #3.

Note that this "negative" aspect of firm diversification applies even in a "frictionless"

world of no transactions costs and where the merger takes place on terms where no premium

above market value is paid for the acquired firm by the acquiring firm. In the real world, the

acquiring firm must usually pay a premium above the market value to acquire a firm. The

premium can range from 5 to more than 100 percent with an average somewhere around 20

percent. A natural question to ask is "Why do the owners of the firm to be acquired demand a

premium for their shares?" While there are several possible explanations, one that is consistent

with our previous analyses is as follows: If the acquiring firm's management is behaving

optimally, then the reason for their making a takeover attempt must be one of the three reasons

discussed at the outset of this section. Since anyone of these three reasons will increase the value

of the acquiring firm's shares, the acquired firm's shareholders are demanding compensation for

providing the means for this increase in value. How this potential increase in value is shared

between the acquiring and acquired firms' shareholders cannot be determined in general (as is the

usual case for bilateral bargaining), but almost certainly, the acquired firm's shareholders will

demand some positive share. Of course, the acquired firm's shareholders do not know what the

acquiring firm's management believes the value of the acquired firm is. Hence, it might appear

that no consolidation could be consummated because whatever price is offered, clearly, the

acquiring firm's management believes it is worth more, and therefore, the acquired firm's

shareholders should demand more. However, the fact that the acquiring firm believes it is worth

more does not mean that it is, indeed, worth more. I.e., their beliefs may be wrong. Hence, at a

293

Robert C. Merton

high enough price above market, the acquired firm's shareholders will take the "sure" premium,

and let the acquiring firm take the risk (and earn the possible reward) that its information is

sufficiently superior to the market's that the acquired firm is still a "bargain."

Whether or not the acquired firm's shareholders or the acquiring firm's shareholders come

out ahead on these takeovers is still an open empirical question. However, it is clear that

acquiring another firm for the sole purpose of diversification is a losing proposition for the

acquiring firm because it must pay a premium for a firm whose acquisition promises no increase

in market value even if it is purchased at market.

While the premium paid over market for the acquiring firm is usually the principal cost of

an acquisition, there are other costs as well which can frequently be substantial.

In an

uncontested merger, there are legal costs and management's time which could be spent on other

activities. There are uncertainties created for the acquired firm's management, suppliers, and

customers which could affect the operations of that firm during the negotiations and subsequent

transition. Of course, if the merger is contested, then litigation costs will be substantial.

Even if it is decided that firm diversification is warranted, then achieving this

diversification through acquisition is very costly. If, because of management risk aversion or

debt capacity or supplier concerns, it is decided that the volatility or total risk of the firm should

be reduced, then this can be achieved much more efficiently (i.e., at lower cost) by simply

purchasing a portfolio of equities and fixed-income securities where no premium must be paid

over market and no significant transactions costs must be paid. If diversification is desired to

provide "cash flow" from these operations to fund growth investments in current operations, then

it is almost certainly less costly to issue securities and raise the funds in the capital markets.

Don't pay $12 to $20 to acquire $10 in cash!

If it is costly for your shareholders to diversify their portfolios by direct purchase of

individual firms' shares, then this service can be provided at less cost by mutual funds,

investment companies, and other financial intermediaries. In summary, there are three types of

reasons for a firm to consider the acquisition of another firm:

294

Finance Theory

1)

Synergy

2)

Taxes

3)

The firm to be acquired is a "Bargain"

They all have in common that the acquisition should increase the value of the acquiring firm's

current stockholders' wealth.

The possibility of a takeover of one firm by another is an important "check" which serves to force

managements to pursue policies which are (at least approximately) value-maximizing.

Diversification by the firm is, in general, not an important objective for the management of the

firm. Hence, if pursued, then a minimum of resources should be used to achieve it. Specifically,

the acquisition of another firm is a costly way to achieve diversification.

Warning:

"diversification" is frequently given as the reason for acquiring a firm by the

acquiring firm's management. If carefully investigated, (most of the time) the meaning of

"diversification" as used is not the one described here, and the real reasons will be one or more of

the three (proper) reasons for making an acquisition.

295