A key challenge of today`s managers is to create “synergy” when

advertisement

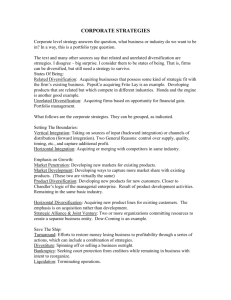

Module 7 Corporate Strategies Chapter Outline A key challenge of today’s managers is to create “synergy” when engaging in corporatelevel strategy decisions and diversification activities. Regrettably, corporate managers do not, in general, have a very good track record in creating value in such endeavors when it comes to mergers and acquisitions. Among the factors that serve to erode shareholder values are paying an excessive premium for the target firm, failing to integrate the activities of the newly acquired businesses into the corporate family, and undertaking diversification initiatives that are too easily imitated by the competition. There are two major types of corporate-level strategy: related and unrelated diversification. With related diversification, the corporation strives to enter into areas in which key resources and capabilities of the corporation can be shared and leveraged. Synergies come from horizontal relationships among business units. Cost savings and enhanced revenues, the intended outcomes of synergy, can be derived from two major sources. First, economies of scope can be achieved from the leveraging of core competencies and sharing activities. Core competencies may be considered to be the “glue” that binds existing businesses together or as the engine that fuels new business growth. To create synergy for a corporation, core competencies must satisfy three conditions: 1. The core competence must enhance competitive advantage(s) by creating superior customer value. (e.g., Gillette) 2. Different businesses in the corporation must be similar in at least one important way to benefit from the core competence. (e.g., Harley Davidson) 3. The core competencies must be difficult for competitors to imitate or find substitutes for (e.g., 3M). Synergy can also be achieved by sharing tangible activities across business units. These include value-creating activities such as common manufacturing facilities, distribution channels, and sales forces. Sharing activities provide cost savings and revenue enhancements. Cost savings come from many sources such as eliminating jobs, facilities, and related expenses that are no longer needed when functions are consolidated. Revenues can be enhanced since an acquiring firm and its target may attain a higher level of sales growth together than either company could do on its own. Firms can also increase the effectiveness of their differentiation strategies via sharing activities among business units. Insert Figure 1 about here Second, market power can be attained from greater, or pooled, negotiating power and from vertical integration. There are two principal means by which firms attain synergy through market power: pooled negotiating power and vertical integration. Note that managers have limits on their ability to use market power for diversification— government regulations can sometimes restrict the ability of a business to gain very large shares of a particular market. For example, the American Online (AOL) and Time Warner merger was approved with conditions that required the merged entity to provide competitors market access. Similar businesses working together or the affiliation of a business with a strong parent can strengthen an organization’s bargaining power in relation to suppliers and customers as well as enhance its position vis-a-vis its competitors. Consolidating an industry can also increase a firm’s market power. Managers must also evaluate how the combined business may affect relationships with actual or potential competitors, suppliers, and customers. For example, PepsiCo was unable to entice McDonald’s as a customer since they had (until recently) competing business units (KFC, Taco Bell, and Pizza Hut). Vertical integration represents an expansion or extension of the firm by integrating preceding or successive productive processes. That is, the firm incorporates more processes toward the original source of raw materials (backward integration) or toward the ultimate consumer (forward integration). For example, Shaw Industries (the carpet producer) has engaged in both backward integration (i.e., acquiring fiber manufacturing facilities) as well as forward integration (i.e., acquiring floor covering retailers). In making decisions associated with vertical integration, four issues need to be considered: 1. Are we satisfied with the quality of the value that our present suppliers and distributors are providing? 2. Are there activities in our industry value chain that are presently being performed by others independently that are viable sources of profits? 3. Is there a high level of stability in the demand for the organization’s products? 4. How high is the proportion of additional production capacity that is actually absorbed by existing products or by the prospects of new and similar products? Insert Figure 2 about here When firms undergo unrelated diversification they enter product-markets that are dissimilar to their present businesses. Unlike related diversification, unrelated diversification derives few benefits from horizontal relationships, that is, the leveraging of core competencies or the sharing of activities across business units in a corporation pursuing unrelated diversification. Instead, the benefits are to be gained from vertical (or hierarchical) relationships, i.e., the creation of synergies from the interaction of the corporate office with the individual business units. There are two main sources of such synergies: 1. the corporate office can contribute to “parenting” and restructuring of businesses, (that typically have been acquired) and 2. the corporate office can add value by viewing the entire corporation as a family or “portfolio” of businesses and allocating resources to optimize corporate goals of profitability, cash flow, and growth. The positive contribution of the corporate office has been referred to as the “parenting advantage.” Many parent companies such as BTR, Emerson Electric, and Hanson create value through management expertise. Cooper Industries is another good example. Its parenting approach is used to improve the performance of an acquired firm’s manufacturing operations; cost accounting systems; and planning, budgeting and human resource systems. Restructuring is another means by which a corporate office can add substantial value to a business. Here, the corporate office tries to find either poorly performing firms with unrealized potential or firms in industries on the threshold of significant, positive change. For restructuring strategies to work, corporate management must have both the insight to detect undervalued companies (otherwise the cost of acquisition would be too high) or businesses competing in industries with high potential for transformation. Also, they must have the requisite skills and resources for turning the businesses around—even if they are new and unfamiliar businesses. Portfolio management is a commonly used technique and is predicated the idea of a balanced portfolio of businesses. This consists of businesses whose profitability, growth, and cash flow characteristics would complement each other, and add up to satisfactory overall corporate performance. The Boston Consulting Group’s growth/share matrix is among the best known of these approaches. Each of the firm’s strategic business units (SBUs) is plotted on a two-dimensional grid, in which the axes are relative market share and industry growth rate. In using a portfolio strategy approach, a corporation tries to create synergies and shareholder value in a number of ways. Since the businesses are unrelated, synergies that develop are the result of the actions of the corporate office interacting with the individual units, i.e., vertical relationships, instead of across business units, i.e., horizontal relationships. Corporations have three primary means of diversifying their product-markets. These are mergers and acquisitions, joint ventures/strategic alliances, and internal development. Growth through mergers and acquisitions (M&A) has played a critical role in the success of many corporations in a wide variety of high technology and knowledge-intensive industries. Here, market and technology changes can occur very rapidly and unpredictably. In addition to speed, M&A can also be a valuable means of obtaining resources that can help an organization to expand its product offerings and services. M&A also can help companies enter new market segments. Exhibit 6.6 lists 10 of the world’s largest recent mergers. As one would expect, there are also some potential downsides to M&A endeavors. These include the expensive premiums that are often paid to acquire a business, difficulties in integrating the activities and resources of the acquired firm into the corporation’s operations, and the fact that competitors may quickly imitate “synergies”. Strategic alliances and joint ventures are assuming an increasingly prominent role in the strategy of leading firms, both large and small. Such cooperative relationships have many potential advantages. Among these are: entry into new markets (the partnership of Time-Warner and three blackowned cable companies in New York City) reducing manufacturing (or other) costs in the value chain (Molson Companies and Carling O’Keefe breweries) developing and diffusing new technologies (STM Microelectronics’s alliances with many of their high-tech customers) There are also many potential limitations associated with strategic alliances and joint ventures. Problems often arise when there are not complementary strengths, limited opportunities for developing synergies, low trust among the partners, and minimal attention given to nurturing close working relationships. Firms can also diversify via corporate entrepreneurship and new venture development. In today’s economy, internal development (or intrapreneurship) is such an important topic by which companies expand their businesses that we dedicate a major portion of an entire chapter to it (Chapter 12—which also addresses entrepreneurship). 3M is an excellent example of a company than embraced the corporate entrepreneurship philosophy. Among the advantages of internal development is the ability to capture all of the value of innovative endeavors (as opposed to sharing with partners). Generally firms may be able to accomplish it at a lower cost than relying on external funding. There are also potential disadvantages such as the time consuming nature of intrapreneurship—which is particularly important in fast-changing competitive environments. Finally, some managerial behaviors may serve to erode shareholder returns. Among these are “growth for growth’s sake”, egotism, and anti-takeover tactics. As we discussed, some of these issues—particularly anti-takeover tactics—raise ethical considerations because the managers of the firm are often not acting in the best interests of the shareholders. Key Terms and Concepts Synergy - when more value is created by individual units (divisions, businesses, departments, etc) working together than if they were separate. Related Diversification - when a company expands by acquiring or developing businesses that are related to its core competencies. Vertical Integration - acquiring a company with similar or complementary core competences in the vertical distribution channel (i.e., value chain). Unrelated Diversification - when a company expands by acquiring or developing businesses that are in unrelated industries and that do not share common core competencies. Restructuring – intention to create value by transforming a firm into a leaner and more effective business by reducing costs and rethinking the firm’s product lines and target markets. Portfolio Management - managing multiple business units within a corporation. Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A) - often the quickest but most expensive means of diversification. Strategic Alliances - when two or more firms form a partnership to carry out a specific project or cooperate in a selected area of business. Corporate Entrepreneurship - when a firm develops new businesses internally (otherwise known as internal venturing.