Cemetery Demography

advertisement

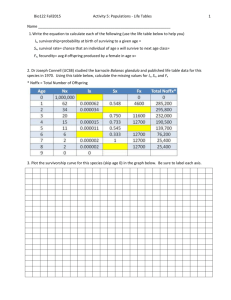

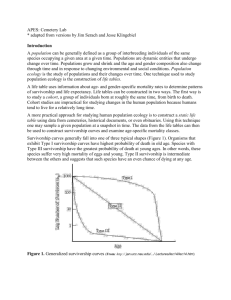

Week 3: Cemetery Demography Before Lab: Read over the lab and be on time. We‟ll be driving today and leaving promptly. DRESS APPROPRIATELY!!! What to Bring to Lab: Bring your lab, a calculator, a hard notebook or clipboard, pencil (pens can freeze) and wear warm clothes including boots. We‟ll be outside for a good portion of the lab. Background: Demography: In last week‟s lab we looked at how theoretical populations grow using models. This week we will focus on demography, which is the study of biological populations, including human populations. Demography includes the study of birth rates, death rates, immigration and emigration patterns which influence population dynamics. Human population dynamics can be particularly interesting because of how events or trends in human history affect them. Everyone has heard the term “Baby Boomers” which refers to the generation that was born after WWII when the economy was strong and soldiers returning from the war were getting married or were reunited with their spouses. This socio-political-economic event is observable in records of human populations via increased birthrate, life expectancy, increased total population and changes in sex ratios in countries affected by the war. Other global events that are evident in population data are the flu pandemic of 1918 which killed between 50 and 100 million people in only 18 months. In the US, this was followed shortly by the Great Depression, which added to the dip in population. There are many such events in human history that have impacted populations, some global and some local. An event that changes a particular population could be as seemingly insignificant as the closing of a mine in a small West Virginia town or increasing housing prices in inner city Boston. Advances in healthcare have also significantly altered demographics in populations. In the early 1800‟s it is reported that one of every five women 1 died during childbirth and infant mortality was much higher than it is today. Obviously childbirth is not nearly as fatal today. These changes have been at least partially attributed to medical breakthroughs such as the discovery of antibiotics in the 1930‟s and the polio vaccine in the 1950‟s. Today we will be looking at local demographics and population dynamics by collecting information from gravestones. From this information we will be able to identify some basic population data as well as compare characteristics of age-classes or “cohorts”. For our gravestone study, a cohort will be all individuals born in the same decade. We will also be using our data to construct survivorship curves. We will be investigating the hypothesis that there are differences in survivorship of cohorts born in the early 1800‟s (1800-1849) compared to individuals born in the late 1800‟s (1850-1899). We will also be examining the data to see if sex plays a role in survivorship both as a whole and between the two time periods. Survivorship Curves: Survivorship curves are representations of population mortality over a lifespan. There are three common forms that these curves can take that represent different life strategies. Figure 1: Survivorship Curves Types I, II and III. I II III Age Different survivorship curves represent the different breeding strategies of organisms. It‟s easy to forget that demography includes all biological populations, not just humans. In Figure 1, line I represents a type I population that experiences little mortality until old age. Species that follow this type of curve often have few offspring and provide parental care for the younger age classes (K strategists). Large animals and ones in the higher trophic levels such as lions, whales and apes often exhibit type I survivorship. Human populations also have survivorship curves that appear most like I. However, 2 how would a human survivorship curve differ from I in areas with high infant mortality? In contrast, species that exhibit type III survivorship represented in Figure 1 often produce many offspring with little or no parental care in the hope that a few will survive to adulthood (R strategists). Some examples of these types of species might include organisms such as octopi, which can lay up to 200,000 eggs. Survival curves can also be calculated for trees which are most often described by a type III curve. Maple trees for example can drop thousands of seeds of which only a handful may ever make it to reproductive maturity. Type II survivorship as seen in Figure 1 is characterized by near constant mortality over all age classes. Obviously, there are few species that exhibit strictly one type of survivorship or another but instead are some combination of type I and III. Cemeteries: Cemeteries are interesting in themselves because they reflect social change and attitudes toward death. Cemeteries prior to the Revolutionary War era, such as some in Boston, have gravestones decorated with grinning skulls and cross-bones and stressed man‟s inevitable fate. Cemeteries were muddy and unkempt, reinforcing this grim message. By the late 1700‟s, death was viewed more as a release from earthly suffering and white marble, a symbol of purity, became common for grave markers. They were often shaped like headboards of beds and the size indicated the age of the deceased. In the 1830‟s cemeteries began to be run by towns rather than churches and it became necessary to buy plots. Grave markers became more ornate and for wealthy families, mausoleums were in vogue. By the late 1800‟s family memorials had a central marker for the head of the family (an adult male), with smaller stones around it representing family members. At this time one out of five women died during childbirth and many children died before the age of five. Thus, death in the immediate family was fairly frequent. Because cemeteries held those recently dead individuals, families would often make weekend excursions to the cemetery and took along picnic lunches. The atmosphere of cemeteries reflected that social pattern and were groomed for a park-like effect. During this century the trend is for husband and wife to have equal and sideby-side headstones stressing the marital bond, rather than the supremacy of the father. I‟m sure you don‟t have to be reminded, but cemeteries are places of honor for those who went before us. Please remember to show respect for the dead 3 and for any other people who may be visiting the cemetery while we gather data. Please respect the privacy of any people visiting graves by avoiding those areas. Methods: Objectives: 1) Compare and explain differences in the survivorship curves in a community with respect to sex and historical trends. 2) Speculate on future changes in demography, based on current community changes. 3) Collect age data and learn how to calculate survivorship using life tables and create survivorship curves. Students will be working in pairs and will each be assigned to collect data in a particular area of the graveyard. Use Table 1 to record individuals. After sampling is complete, data will be compiled into cohorts, which for this study will be defined as all of the individuals born in a particular decade. To ensure that we account for each individual that was born into a particular cohort, we must be sure that none are still surviving. For this reason, all of the individuals recorded should have birth years prior to 1900. To get an adequate sample size, each group will be asked to record year of birth, death and age of death for as many individuals as they can in a given amount of time. The sex of the decedent should also be indicated so that we will be able to see if there are differences between male and female survivorship. Information should be filled in using Table 1 provided. Notes: * If a name is ambiguous to sex, omit that individual. * Also, if only a death date and age at death are given, calculate year of birth and keep that individual. * Be sure not to only focus on large tomb stones, since this could be influenced by wealth and quality of healthcare. * Do your best to read the grave stones. If they are illegible, you may want to use crayons and make a rubbing if they are available. Data Analysis: After Class: 1) For each individual you recorded in the cemetery, calculate the age at death to complete Table 1. You will be putting this information into an Excel spreadsheet and emailing it to your TA. You will also be emailing a summarized version of your data. (The tables you have to fill in and return electronically will be sent to your email this week) 4 2) The summary of your data will be made by grouping each of your individuals into cohorts by decade and by sex (1 per pair). Cohorts as previously stated will be defined as individuals born in the same decade. Note that the data will be clustered into age classes of ten year intervals. For the 0-9 age class, count all of the individuals who died at an age of 9 or less. For the 10-19 year age class count all of the individuals who died at an age of 10 to 19 and so on. 3) To summarize the data for the whole class, your extremely talented TA‟s will use your emailed data to compile the results and then distribute that data to you for use in your lab report. In class: 1) You will be making life tables based on data supplied by your TA. You should make one for men and one for women using Table 3 and the following instructions as a guide. Numerical definitions can also be found in your Primer of Ecology textbook in Chapter 3. 2) The second column is the first you need to fill in (dx). This represents the number of individuals that died at the age indicated in column one. The third column is for the number of individuals surviving at each age step (Sx) and indicates the number of individuals remaining in the population. The calculations of these data are cumulative. Begin by placing a zero in the lowest box of the column. To determine the number for the next box up, add to the zero the number of deaths (dx) that appears in the column to the left and one row up. Continue this process of adding on the number to the left and one row up to determine the data for each row of the survivorship column. When you reach the top you should have the total number of individuals that you originally counted. 3) Now calculate the proportional survivorship by dividing each number in the Sx column by the total number of individuals you counted of that sex and enter it into the next column. This should be the proportional survivorship. (The first box should equal 1 and the last 0) This will allow you to compare data between sexes even if you did not count the same number of individuals in each. 4) The next column is Log Survivorship and is self-explanatory. Simply take the natural log of your proportional survivorship. 5) The last column, probability of survival gx, should then be filled in. This column represents the probability that an individual will make it to that age class. 5 6) Make your own survivorship curves with age classes and proportional survivorship. Assignment. This lab will form the basis of a long lab report. You will be expected to calculate and compare survivorship curves for males and females in the early and late 18th century. Your results will be presented in a formal lab report. We will discuss the format of your report in lab and you will be able to download detailed instructions on the format of the lab report. Your report will be due in class on Wednesday, February 20. This schedule is also posted on the course WebCT site under „Schedule‟. 6