Be They Fish Or Not Fish: The Fishy Registration of Nonsexual

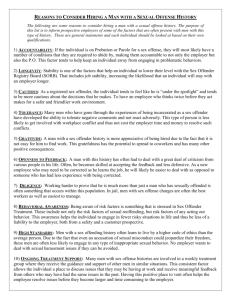

advertisement