Traded Sector Final

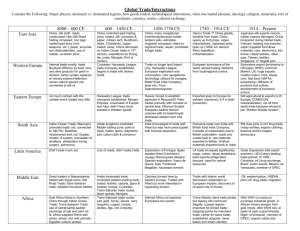

advertisement

The Traded Sector in Portlandʼs Regional Economy Prepared for the Portland Business Alliance A pr il 20 12 Eugene th 99 W. 10 Avenue, Suite 400 Eugene, OR 97401 541.687.0051 Portland 222 SW Columbia, Suite 1600 Portland, OR 97201 503.222.6060 www.econw.com © 2012 ECONorthwest This page intentionally left blank. CONTACT INFORMATION This report was prepared by Dr. Bryce Ward, Terry Moore, John Tapogna, and Paul Thoma of ECONorthwest, which is solely responsible for its content. ECONorthwest specializes in economics, planning, and finance. Founded in 1974, we’re one of the oldest independent economic consulting firms in the Pacific Northwest. ECONorthwest has extensive experience applying rigorous analytical methods to examine the benefits, costs, and other economic effects of environmental and natural resource topics for a diverse array of public and private clients throughout the United States and across the globe. For more information about ECONorthwest, visit our website at www.econw.com. For more information about this report, please contact: Bryce Ward ECONorthwest 222 SW Columbia Street Portland, OR 97201 503-222-6060 ward@econw.com ECONorthwest The Traded Sector in Portlandʼs Regional Economy i This page intentionally left blank. TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTACT INFORMATION ....................................................................................................... I TABLE OF CONTENTS ......................................................................................................... III EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 1 I. WHAT IS THE TRADED SECTOR? ..................................................................................... 3 II. HOW DOES THE TRADED SECTOR DIFFER FROM THE LOCAL SECTOR? ................................ 6 III. HOW DOES THE TRADED SECTOR CHANGE OVER TIME? .................................................... 8 IV. HOW DOES PORTLAND COMPARE TO OTHER CITIES? ...................................................... 11 Traded Goods ............................................................................................................................... 13 Traded Services ............................................................................................................................ 14 Local ............................................................................................................................................. 16 A look to the future ........................................................................................................................ 18 V. HOW DOES THE TRADED SECTOR AFFECT THE REGIONAL ECONOMY? .............................. 20 VI. WHY DOES INDUSTRY MIX AND HEALTH OF THE TRADED SECTOR VARY ACROSS REGIONS?28 APPENDIX A. RAW HISTORICAL DATA FOR FIGURES 3-8 ....................................................... 1 ECONorthwest The Traded Sector in Portlandʼs Regional Economy iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In this report, we describe the role of the traded sector in Portland’s regional economy. The traded sector includes industries and firms who produce goods and services that are consumed outside the region of production. In contrast the local (or non-traded) sector consists of industries and firms who produce goods and services that are consumed locally, in the region they were produced. Most forms of manufacturing, specialized design services, advertising, and management and technical consulting are concentrated and, therefore, classified as traded in our analysis. Retail and wholesale trade, construction, healthcare, education, real estate, food services, and waste management are found in cities and towns across the country, and most fall into the local sector. Overall, approximately one in three jobs in the US are in the traded sector. Specifically, we highlight the following: (1) Portland’s traded sector pays higher wages, on average ($51,600 vs $36,300), employs more full-time workers (70% vs 56%), and employs more college graduates (40% vs 31%) than the local sector. (2) The traded sector is not static. It changes over time. Over the past forty years, the share of traded sector employment in the traded goods sector has declined substantially as employment in traded services has grown. In Portland, the traded sector is constantly in flux as old industries die, new industries emerge, and industries move from one region to another. Over the past forty years, the largest traded sector industries changed from wood products, agriculture, and shipping to electronics, computers, and other business services. (3) Variation in regional economic performance is tied to differences in the composition and performance of regional traded sectors. Across metro areas, the traded sector typically makes up 35-40 percent of total employment, however, the industries that comprise each area’s traded sector differ. Over the past 40 years, Portland’s traded goods sector has performed well – increasing employment and wages at a rate faster then the US metro average; however, over the past 10 years, Portland’s traded goods sector has lost employment and wages have fallen. Over the past 40 years, Portland’s traded services sector has grown rapidly. Relative to all US metro areas, Portland’s traded service sector saw greater employment growth, but slightly slower wage growth; however, wage growth in Portland’s traded service sector significantly lags growth in areas like Seattle, Minneapolis, and Denver, particularly since 1990. As such, we argue that a significant portion of Portland’s declining income relative to ECONorthwest The Traded Sector in Portlandʼs Regional Economy 1 some metro areas is the result of lagging wage growth in the traded services sector. (4) Economic theory suggests and empirical research confirms that the health of a region’s traded sector significantly affects regional employment growth, income growth, and housing prices. Growth in the traded sector generates growth in the local sector, more people and more money means more customers for local businesses. On average, one additional traded sector job creates 1.6 local sector jobs. The traded sector also significantly influences regional income and price differences. Higher productivity and wages in the traded sector generate higher wages in the local sector and higher wages throughout the region tend to increase the cost of living (e.g., housing prices). (5) Over the long-run, variation in traded sector (and thus regional economic) performance across regions stems from differences in regional economic capacity (e.g., natural resources, workforce skills, transportation infrastructure, social norms and governing institutions, innovative ability). Regional economic capacity is not solely a function of the traded sector. The local sector plays an important role in affecting regional economic capacity, utilization, and the health of the traded sector. In the remainder of this report, we provide more detailed answers to six questions about the traded sector and its role in the regional economy: (1) What is the traded sector? (2) How does the traded sector differ from the local sector? (3) How has the traded sector changed over time? (4) How does Portland compare to other cities? (5) How does the traded sector affect the regional economy? (6) Why does industry mix and health of the traded sector vary across regions? ECONorthwest The Traded Sector in Portlandʼs Regional Economy 2 I. WHAT IS THE TRADED SECTOR? All firms engage in trade with households, other businesses, and governments. Trading is fundamental to the efficiency of economic activity: it allows specialization, economies of scale and scope, and the exploitation of comparative advantages. The nature of any firm’s goods and services determines where trade takes place. Some good and services are traded locally (within the region in which they are produced); some are traded domestically (outside of the region of production but within the US), and some are traded globally (outside the country of production). All of these traders play important roles in the health of a regional economy. This report focuses on the characteristics and economic contributions of firms that sell their products outside their region of production—either domestically or globally. It classifies domestic and global traders as part of the “traded” sector, which it compares to the “local” sector. Competing definitions of traded sector exist, and technological advances— like the Internet—keep the sector’s boundaries in flux. Despite the sometimes varied and evolving definitions, economists agree traded and local industries differ in a number of important ways, including the characteristics of their workers, the output produced per worker, and average wages earned. Many factors contribute to technical difficulties in defining the traded sector, and in interpreting information about it. Many large businesses are multi-faceted and have components that trade heavily and others that do not. Even small, single-product manufacturing firms may sell primarily to a local market. A carry-over from prior theories of economic development, the term “basic industry” has usually connoted manufacturing, but in today’s economy the trading of services is a big component of domestic and global trade. In this report, we classify industries as traded or local-sector industries following the approach developed by economists J. Bradford Jensen and Lori Kletzer.1. Jensen and Kletzer classify industries based on their geographic concentration of industrial activity. If an industry is highly concentrated in a small number of metropolitan areas, it must be exporting its goods or services to other countries or regions within the US. Conversely, if an industry is found Jensen, J.B. and L. Kletzer, 2005. “Tradeable Services: Understanding the Scope and Impact of ServicesOffshoring.” Brookings Trade Forum 2005: 75-116. 1 ECONorthwest The Traded Sector in Portlandʼs Regional Economy 3 everywhere, then individual businesses in that industry are probably mainly trading in the local market.2 Table 1 presents the share of major industry categories classified as traded in the US overall and in the Portland metropolitan area. Most forms of manufacturing, specialized design services, advertising, and management and technical consulting are concentrated and, therefore, classified as traded in our analysis. Retail and wholesale trade, construction, healthcare, education, real estate, food services, and waste management are found in cities and towns across the country, and most fall into the local sector. Specifically, we classify industries into the traded and local sector by calculating the gini coefficients described by Jensen and Kletzer using 2000 census micro data obtain from the Integrated Public-Use Microdate Series (IPUMS). Throughout this analysis, we examined data from the 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000 censes and the 2010 American Community Survey. These datasets frequently code industries into different categories. Using the industry classification from 2000 (augmented with gini coefficients from 2010 for industreis that were not classified in 2000), we code all industries from each data set as traded or local by translating NAICS codes into ind1990 codes (which provide a consistent description of industries across years). IPUMS citation: Steven Ruggles, J. Trent Alexander, Katie Genadek, Ronald Goeken, Matthew B. Schroeder, and Matthew Sobek. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 5.0 [Machine-readable database]. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2010 (IPUMS USA hereafter).. 2 ECONorthwest The Traded Sector in Portlandʼs Regional Economy 4 Table 1. Share of Major Industry Categories Classified as Traded, 2010 Industry Portland US Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing and Hunting 100% 100% Mining, Quarrying, and Oil and Gas Extraction 100% 100% Manufacturing 1 100% 100% Other Manufacturing 100% 100% Management of Companies and Enterprises 100% 100% Manufacturing 2 95% 96% Real Estate and Rental and Leasing 91% 94% Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services 87% 86% Manufacturing 3 86% 85% Finance and Insurance 67% 66% Information 71% 64% Transportation and Warehousing 61% 59% Postal Service, Couriers and Messengers, Warehousing & Storage 57% 58% Wholesale Trade 43% 43% Administrative and Support and Waste Management & Remediation Services 37% 40% Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation 53% 36% Public Administration 16% 29% Utilities 18% 20% Other Services (except Public Administration) 20% 15% Accommodation and Food Services 12% 13% Retail Trade 8% 7% Store Retailers 6% 6% Health Care and Social Assistance 2% 2% Educational Services 1% 1% Construction 0% 0% Other Retail 0% 0% Source: ECONorthwest analysis of U.S. Census and American Community Survey data. Based on this approach, about 33 percent of all jobs in U.S. are in the domestically or globally traded sectors. An alternative approach, which looked at export data and limited the definition to globally traded industries, estimated about one-quarter of US jobs to be in the traded sector. ECONorthwest The Traded Sector in Portlandʼs Regional Economy 5 II. HOW DOES THE TRADED SECTOR DIFFER FROM THE LOCAL SECTOR? Differences between traded and local sectors are not limited to differences in their locations relative to their customers. While both sectors include large firms and small firms, young firms and old firms, and high-wage and low-wage firms, on average, the traded and local sectors differ in several important ways. Historically, the amount of output (or “value added”) per job has been higher in traded sector industries. Across industries, one can compare the value of the output (related to Gross Domestic Product) to the number of jobs require to produce it. The division yields a measure of value added per worker. If a job in the US is tied to the global supply chain and has a low value-added, it is at-risk of being outsourced to a foreign location where labor is less costly. In manufacturing, for example, a combination of outsourcing and automation over the past several decades has eliminated lower value-added US jobs in the traded sector. Such dynamics are less prevalent in the local sector. The growth in value added per job in the traded sector accelerated during the past decade and outpaced the growth in value added in the local sector.3 Outsourcing and automation continued. In addition, the traded sector had a surge in value added per worker in a number of sectors. Notably, the electronics sector expanded exponentially the computing power available at a given price. Workers in the traded sector tend to be better educated, work more hours, and earn higher average wages. On average, traded sector workers earn more than local sector workers. In Portland, the average annual wage for traded sector workers is $51,600 and the average annual wage in the local sector is $36,300.4 Consistent with this result, traded sector workers are also more likely to have a college degree and are more likely to work full time.5 Spence and Hlatschwayo (2011) estimate that between 1990 and 2008 value added per job increased by 44 percent, but the economy overall only experienced a 21 percent increase in value added per job. 3 When calculating average wages using the American Community Survey we exclude respondents who indicate they are employed but who report $0 in wages from the calculations. 4 These results are “on average.” Traded sector firms still have lower paying jobs in administration and maintenance, but they have a greater proportion of jobs in higher-paying occupations like management, finance, and engineering. 5 ECONorthwest The Traded Sector in Portlandʼs Regional Economy 6 Table 2. Characteristics of Traded vs. Local Sectors, 2010 Portland US Traded Mean annual income Traded Local $51,600 $36,300 $51,000 $34,600 70% 56% 72% 59% $27.77 $23.54 $27.59 $20.75 40% 31% 33% 26% Share Full-time Mean hourly wage Local Share with BA Source: IPUMS USA; ECONorthwest analysis of U.S. Census and American Community Survey data. Traded sector jobs have grown slowly—if at all. By one estimate, the traded sector added only 620,000 jobs during 1990-­‐2008— or about 2 percent of total job growth in the U.S.6 By contrast, the local sector has grown at a much higher rate. Therefore, as shown in Figure 1, employment in the traded sector has become a smaller percentage of total employment. Figure 1. Share of Jobs in the Traded Sector, 1970-2010 USA 70% 60% 50% 40% Local 30% Traded 20% 10% 0% 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 Source: IPUMS USA; ECONorthwest analysis of U.S. Census and American Community Survey data. 6 Spence and Hlatschwayo (2011) ECONorthwest The Traded Sector in Portlandʼs Regional Economy 7 III. HOW DOES THE TRADED SECTOR CHANGE OVER TIME? The economy changes over time, and the traded sector changes along with it. Over the past several decades, the U.S. traded sector has shifted from predominantly goods producing to predominantly services producing. Figure 2 presents the employment trends in traded goods and traded services sectors. Employment in traded goods has stagnated and fallen, but employment in traded services has grown rapidly. This transition reflects a number of factors – growth in global trade, technological change, including computers and the internet, etc., but it helps to illustrate a key fact – the traded sector is not a static entity (or set of entities). It can and will change over time. Figure 2. Traded Sector Employment, 1970-2010 USA 40,000,000 35,000,000 30,000,000 25,000,000 20,000,000 Traded Goods 15,000,000 Traded Services 10,000,000 5,000,000 0 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 Source: IPUMS USA; ECONorthwest analysis of U.S. Census and American Community Survey data. Traded sector evolutions are even more pronounced at the regional level. The perpetual birth, death, or movement of industries (and firms) means that each region’s traded sector is constantly in flux. Sometimes a region’s traded sector will change when a new, growing industry finds a home there (e.g., the auto industry was not always concentrated around Detroit and high-tech was not always concentrated in Silicon Valley; as these industries emerged they started out spread across many locations before concentrating in a few places).7 Sometimes a region’s traded sector will change when an old industry peters out (e.g., Rochester, NY is currently adapting to the decline in photofinishing Klepper, S., 2010. "The origin and growth of industry clusters: The making of Silicon Valley and Detroit," Journal of Urban Economics, 67(1), pages 15-32. 7 ECONorthwest The Traded Sector in Portlandʼs Regional Economy 8 brought about by the growth of digital photography and sharing via the internet). Finally, sometimes a region’s traded sector will change in response to the movement of industries across places (e.g., the center of the photographic industry moved to Rochester from New York City following George Eastman invention of roll film).8. The process via which regions cope with the loss of old, dying industries, birth and nurture new industries, or attract existing industries from other locations lies at the crux of debates about regional economic development policy. Changes in the composition of regional economic activity can be large and swift. Every 5 years, 1.5 percent of city sectors will fall from the top decile to the bottom decile.9 That is, if a city finds itself in the top 10 percent of cities in terms of employment in a particular industry, there is a 1.5 percent chance that, within five years, it will find itself in the bottom ten percent of cities in terms of employment in this industry. For instance, an analysis of the movement of the information technology sector between 1989 and 2002 found that, while overall employment in information technology grew by over 20 percent during this period, growth varied across regions.10 Some places (e.g., Washington DC, San Francisco, Atlanta) saw employment grow by more than 50%, while other places (e.g., Dutchess, NY and Colorado Springs – which started the period among the top 25 regions) saw their employment in the sector fall by more than 50%. Table 3 shows changes to the composition of Portland’s traded goods and traded services sectors over the past 40 years. In 1970, the traded sector in the Portland area was concentrated in agriculture and timber (traded goods) and the movement of goods (railroads and ports) to other places (traded services). Today, the dominant industries from 1970 still play a role in Portland’s traded sector, but other industries (like computer and electronics manufacturing and engineering and architecture) have risen to prominence. Duranton, G. 2007. "Urban Evolutions: The Fast, the Slow, and the Still," American Economic Review, 97(1), pages 197-221. 8 9 Duranton (2007) Wallace, N. and D. Walls, 20004. “Agglomeration Economies and the High-Tech Computer Cluster.” Unpublished manuscript. 10 ECONorthwest The Traded Sector in Portlandʼs Regional Economy 9 Table 3. Compositional Changes in Portlandʼs Traded Sector Traded Goods Traded Services Growing Share Electrical machinery, equipment, and supplies, Computers and related equipment, Motor vehicles and motor vehicle equipment, Medical, dental, and optical instruments and supplies Computer and data processing, Engineering and architecture, Real estate, Management and public relations Shrinking Share Agricultural production – crops, Sawmills planning mills and millwork, Pulp paper and paperboard mills, Canned, frozen, and preserved fruits and vegetables Insurance, Railroads, Water Transportation, Telephone Communications Source: IPUMS USA; ECONorthwest analysis of U.S. Census and American Community Survey data. ECONorthwest The Traded Sector in Portlandʼs Regional Economy 10 IV. HOW DOES PORTLAND COMPARE TO OTHER CITIES? Since traded sector industries concentrate in a few locations and sell to people across a wider area, every region will have a different mix of industries in its traded sector. Table 4 presents key traded sector industries for several regions (specifically we include Portland, Seattle, Minneapolis, Denver, Sacramento, St. Louis, and Cincinnati).11 While there is some overlap in key industries across the regions examined, each region has its own mix of traded sector industries. Interestingly, the size of each region’s traded sector remains fairly constant across metro areas (approximately 35%-40% of total employment). We’ve used these cities as comparison cities for Portland in previous reports for the Portland Business Alliance. 11 ECONorthwest The Traded Sector in Portlandʼs Regional Economy 11 Table 4. Significant Regional Traded Sector Industries Region Portland, OR Seattle, WA Significant Traded Goods Industries 1. Electrical machinery, equipment, and supplies 1. Real estate, including real estate-insurance offices 2. Agricultural production, crops 2. Insurance 3. Motor vehicles and motor vehicle equipment 3. Computer and data processing services 1. Guided missiles, space vehicles, and parts 1. Computer and data processing services 2. Aircraft and parts 2. Real estate, including real estate-insurance offices 3. Electrical machinery, equipment, and supplies 1. Medical, dental, and optical instruments and supplies 2. Electrical machinery, equipment, and supplies Minneapolis, MN Denver, CO 3. Insurance 2. Real estate, including real estate-insurance offices 3. Social services 1. Motor vehicles and motor vehicle equipment 1. Insurance 2. Soaps and cosmetics 3. Real estate, including real estate-insurance offices 3. Drugs 44% 1. Insurance 3. Computers and related equipment 2. Aircraft and parts St. Louis, MO 38% 2. Computer and data processing services 1. Motor vehicles and motor vehicle equipment 36% 3. Business services 2. Oil and gas extraction 3. Electrical machinery, equipment, and supplies 35% 2. Computer and data processing services 1. Real estate, including real estate-insurance offices 3. Medical, dental, and optical instruments and supplies Traded Sector share of total employment 1. Insurance 1. Electrical machinery, equipment, and supplies 2. Agricultural production, crops Cincinnati, OH 3. Management and public relations services 3. Miscellaneous manufacturing industries 1. Electrical machinery, equipment, and supplies Sacramento, CA Significant Traded Services Industries 39% 2. Personnel supply services 39% 1. Insurance 2. Real estate, including real estate-insurance offices 3. Security, commodity brokerage, and investment companies 33% Source: IPUMS USA; ECONorthwest analysis of U.S. Census and American Community Survey data. In previous work for the Portland Business Alliance, we have noted that. income in Portland lags places like Seattle, Minneapolis, and Denver and is more inline with Sacramento, St. Louis, and Cincinnati. The figures we describe below indicate that differences in the industry mix and performance of the traded sector – particularly the traded services sector – helps to explain this pattern of results. ECONorthwest The Traded Sector in Portlandʼs Regional Economy 12 Traded Goods Figures 3 and 4 present the percentage change in traded goods employment and average wages for Portland and the seven comparison regions between 1970 and 2010. Relative to these comparison areas, Portland’s traded goods sector performed well. Figure 3. Percent Change in Traded Goods Employment since 1970 300% 250% Portland, OR 200% Seattle, WA 150% Minneapolis, MN Denver, CO 100% Sacramento, CA 50% Cincinnati, OH St. Louis, MO 0% 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 -­‐50% USA Metros -­‐100% Source: IPUMS USA; ECONorthwest analysis of U.S. Census and American Community Survey data. ECONorthwest The Traded Sector in Portlandʼs Regional Economy 13 Figure 4. Percent Change in Inflation-Adjusted Mean Wages for the Traded Goods Sector, 1970-2010 80% 70% Portland, OR 60% Seattle, WA 50% Minneapolis, MN 40% Denver, CO 30% Sacramento, CA 20% Cincinnati, OH 10% St. Louis, MO 0% -­‐10% 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 USA Metros -­‐20% Source: IPUMS USA; ECONorthwest analysis of U.S. Census and American Community Survey data. Employment in Portland’s traded goods sector increased 40% relative to 1970 (although employment declined between 2000 and 2010). Portland’s employment growth in traded goods outpaced the US metro area average and all of the other comparison regions except Sacramento. Looking only at the last 10 years, nearly all of the examined regions lost traded goods employment, and Portland’s decline was comparable to most of the comparison areas. Inflation-adjusted wage growth in Portland’s traded goods sector was also relatively strong, growing 60% over the period. Wage growth in Portland’s traded goods sector was faster than the US metro average and all of the comparison regions except Sacramento; however, Portland lost ground to several comparison cities (e.g., Seattle, Minneapolis, and Denver) over the past decade. In 1970 wages in Portland were low relative to these comparison areas. As such, even though wages in Portland grew relatively quickly, they remain low relative to most of the comparison areas. The average wage in Portland’s traded goods sector is approximately $56,000 per year. This exceeds the US metro average of approximately $52,000, but falls below the average in some of other comparison regions like Seattle ($67,600), Denver ($63,700), Minneapolis ($60,600), and Cincinnati ($59,100). Traded Services Figures 5 and 6 present the percentage change in traded service employment and average wages for Portland and the seven comparison regions between 1970 ECONorthwest The Traded Sector in Portlandʼs Regional Economy 14 and 2010. In this sector, Portland’s performance is relatively typical for US metro areas but falls below several standout regions. Figure 5. Percent Change in Traded Services Employment since 1970 300% 250% Portland, OR 200% Seattle, WA 150% Minneapolis, MN Denver, CO 100% Sacramento, CA 50% Cincinnati, OH St. Louis, MO 0% 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 -­‐50% USA Metros -­‐100% Source: IPUMS USA; ECONorthwest analysis of U.S. Census and American Community Survey data. Figure 6. Percent Change in Inflation-Adjusted Mean Wages for Traded Services Sector, 1970-2010 80% 70% Portland, OR 60% Seattle, WA 50% Minneapolis, MN 40% Denver, CO 30% Sacramento, CA 20% Cincinnati, OH 10% St. Louis, MO 0% -­‐10% 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 USA Metros -­‐20% Source: IPUMS USA; ECONorthwest analysis of U.S. Census and American Community Survey data. ECONorthwest The Traded Sector in Portlandʼs Regional Economy 15 As described previously, employment growth in traded services exploded over this period. Portland’s growth in traded service employment was slightly faster than the US metro average (206% vs. 187%), much faster than St. Louis and Cincinnati (both less than 90%), but somewhat slower than Seattle and Denver (both more than 225%). Wage growth in Portland’s traded services sector was slightly slower than in all US metro areas (29% vs 30%) and substantially slower than in cities likely Seattle, Minneapolis, and Denver (all of which had traded service wages increase by more that 45%). Portland’s slower wage growth relative to these areas is the result of slower wage growth since 1990. Given that Portland’s traded goods wages grew more rapidly than these areas over the period examined, this suggests that differences in the traded services sector contribute substantially to Portland’s declining income relative to these regions. In 2010, wages in Portland’s traded services sector lagged the US Metro average ($47,200 vs. $52,300) and all of the comparison areas. While Portland’s wages were close to Sacramento, St. Louis, and Cincinnati’s (all in $47,000$49,000 range), Portland’s traded service wages are significantly below Seattle ($61,400), Minneapolis ($56,700), and Denver ($56,200). Local To complete the comparison, Figures 7 and 8 present the percentage change in local sector employment and average wages for the local sectors in Portland and the comparison regions. The pattern here is similar to that described for traded services – Portland saw relatively strong employment growth and relatively weak wage growth. ECONorthwest The Traded Sector in Portlandʼs Regional Economy 16 Figure 7. Percent Change in Local Employment since 1970 300% 250% Portland, OR 200% Seattle, WA 150% Minneapolis, MN Denver, CO 100% Sacramento, CA 50% Cincinnati, OH St. Louis, MO 0% 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 -­‐50% USA Metros -­‐100% Source: IPUMS USA; ECONorthwest analysis of U.S. Census and American Community Survey data. Figure 8. Percent Change in Inflation-Adjusted Mean Wages for the Local Sector, 1970-2010 80% 70% Portland, OR 60% Seattle, WA 50% Minneapolis, MN 40% Denver, CO 30% Sacramento, CA 20% Cincinnati, OH 10% St. Louis, MO 0% -­‐10% 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 USA Metros -­‐20% Source: IPUMS USA; ECONorthwest analysis of U.S. Census and American Community Survey data. Employment in Portland’s local sector grew by 159% between 1970 and 2010. This was slightly below the US metro average (179%), Sacramento (210%), and ECONorthwest The Traded Sector in Portlandʼs Regional Economy 17 Denver (168%), but above Seattle (137%), Minneapolis (129%), St. Louis (84%) and Cincinnati (72%). Wage growth in the local sector was slower than in the traded sector. Portland’s local sector wages grew by 12% an amount roughly equal to the US metro average (13%). However, with the exception of St. Louis (9%), all of the other comparison areas experienced faster wage growth (ranging from Cincinnati at 15% to Denver at 23%). Local sector wages, though, do not vary by as much as traded sector wages across regions. Portland’s average local wage is approximately equal to the US metro average ($36,900 vs $36,800), and does not fall that much below high wage regions like Seattle ($39,100), Minneapolis ($39,300), and Denver ($37,400). A look to the future The figures above describe how Portland’s traded sector has performed over the past 40 years, but how might it perform in the future. Is Portland poised to grow faster or slower than other regions? While it is difficult to predict which industries will be important to Portland’s future traded sector and how these industries will perform. If we assume that Portland’s economy will have roughly the same industry mix as it does today, we can use industry level forecasts to obtain a crude sense of how Portland’s economy might perform into the future. Economist Jed Kolko recent conducted such an analysis. His analysis (presented in the Figure 9) uses industry job growth forecasts produced by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) to project job growth region.12 Kolko assumes that local industry mix remains constant and growth in each region follows the BLS forecast. To help account for the fact that regional industry mixes can change and other factors may affect growth, Kolko adjusts his prediction to account for local factors like education, density, and climate that economists expect to affect job growth. While the BLS forecasts (like all forecasts) are unlikely to work out perfectly, this map illustrates what current industry mix and expected economic trends project for regional economic fortunes. Portland’s current industry mix places it the lower middle group of regions. 12 http://trends.truliablog.com/2012/02/where-the-jobs-will-be-in-2020/ ECONorthwest The Traded Sector in Portlandʼs Regional Economy 18 Figure 9. Projected Job Growth, 2010-2020, Based on All Factors Source: "Where the Jobs Will Be in 2020." Jed Kolko, Trulia Chief Economist. February 8, 2012. ECONorthwest The Traded Sector in Portlandʼs Regional Economy 19 V. HOW DOES THE TRADED SECTOR AFFECT THE REGIONAL ECONOMY? The traded sector plays an important role in local economies. Economic theory suggests and empirical research confirms that the health of a region’s traded sector significantly affects regional employment growth, income growth, and housing prices. Growth in the traded sector generates growth in the local sector. The health of the region’s local sector is directly tied to the health of the region’s traded sector. As employment and incomes in the region increase, demand for local goods increase. More people and more money means more customers for local grocery stores, restaurants, hairdressers, carpenters, etc. Figure 10 helps to illustrate this relationship. Figure 10 presents the correlation between the growth in regional traded sector employment and growth in local sector employment between 1980 and 2010. This figure clearly shows that regions that experience faster traded sector growth experience faster local sector growth. ECONorthwest The Traded Sector in Portlandʼs Regional Economy 20 Change in Local Employment (Thousands) Figure 10. Change in Local Employment vs. Change in Traded Employment, 19802010 2,000 1,500 1,000 500 Portland 0 -­‐400 -­‐200 0 200 400 600 800 1,000 -­‐500 Change in Traded Employment (Thousands) Source: IPUMS USA; ECONorthwest analysis of U.S. Census and American Community Survey data. However, as any undergraduate statistics student knows, correlation does not prove causation. One may wonder if (or to what extent) traded sector growth causes local sector growth. Several recent studies find evidence of strong relationships between a region’s traded sector and its local sector. For instance, one recent estimate developed by economist Enrico Moretti suggest that, on average, one additional traded sector job creates 1.6 additional jobs in the local sector.13 Effects, though, vary by industry. An additional high-skill traded sector is associated with 2.5 local sector jobs, and an additional low-skill traded sector jobs is associated with one additional local sector job. Growth in one part of a region’s traded sector can have both positive and negative effects on other parts of the region’s traded sector. Moretti, E., 2010. “Local Multipliers” American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings 100: 1-7; several other studies find evidence that traded sector growth generates local sector growth, e.g., Mendel, B., 2012. “Local Multiplier: Theory and Evidence.” Unpublished manuscript, Nakamura, E. and J. Steinsson, 2012. “Fiscal Stimulus in a Monetary Union: Evidence from U.S. Regions” NBER Working Paper 17391; Autor, D., D. Dorn, and G. Hansen, 2011. “The China Syndrome: Local Labor Marker Effects of Import Competition in the United States.” NBER Working Paper 18054. 13 ECONorthwest The Traded Sector in Portlandʼs Regional Economy 21 Growth in one part of the traded sector may also affect the health of the rest of the traded sector. These effects may be positive or negative. On the positive side, growth in a region’s traded sector may increase the efficiency and productivity (and thus employment and wages) of the rest of the traded sector due to the advantages of clustering (which economists refer to as agglomerative economies).14 On the negative side, growth in the traded sector may drive up wages, housing prices, or other local costs, and cost increases may lead some firms to close or move elsewhere, decreasing employment. Both of these effects are real. Which effects is larger depends, in part, on the specific context; however, on average, across all cities, Moretti finds no net effect of growth in one part of the traded sector on other parts of the traded sector.15 Over the long-run, a region’s traded sector also may provide seeds and fertilizer for new traded sector industries. As discussed previously, the industry mix of a region’s traded sector will change overtime. Some changes stem from the creation of new industries and the decline of old ones. Other changes stem from the movement of industries across locations. The characteristics of a region’s current traded sector, in part, explain how the traded sector will evolve over time. We discuss these effects in more detail in the next section. Regional income (and price) differences reflect differences in traded sector productivity. Figure 11 describes the relationship between traded sector wages and local sector wages. This figure describes the clear correlation between changes to traded sector income and changes to local sector income for US metropolitan areas. Again, the question becomes to what extent do changes to traded sector incomes cause the changes to local sector incomes? Agglomerative economies is economic jargon for the efficiencies created by clustering. Firms enjoy cost saving when they locate near each other due to better knowledge flow (knowledge spillovers), better access to specialized intermediate goods and services, and more robust labor markets. 14 15 Moretti (2010) ECONorthwest The Traded Sector in Portlandʼs Regional Economy 22 Change in Local Real Mean Wages (Thousands) Figure 11. Change in Local Real Mean Wages vs. Change in Traded Real Mean Wages, 1980-2010 $50 $40 $30 Portland $20 $10 $0 $0 $20 $40 $60 $80 $100 $120 Change in Traded Real Mean Wages (Thousands) Source: IPUMS USA; ECONorthwest analysis of U.S. Census and American Community Survey data. Based on a prominent economic theory (known as the Balassa-Samuelson effect), economists argue that much of the difference in income (and prices) across places stems from differences in the productivity of the traded sector.16 The logic behind this theory is as follows. Traded sector firms, by definition, compete in large, cross-regional markets. As such, the price of traded products is constrained to a range determined by the prices charged by competitors from other regions. Thus, if workers in Portland want to earn more than workers in another region producing the same good for a similar price, then Portland workers must be more productive. Higher productivity leads to higher traded sector wages that may spill over into the local sector. To the extent that local firms and traded sector firms compete for the same workers, the local sector firms must pay higher wages to attract employees.17 As a result, higher incomes in a regional economy stem from higher productivity in the traded sector. 16 Avent, R., 2011. The Gated City. E.g., Beaudry, Green, and Sand (2007) develop this theory and find strong empirical evidence that suggests that shifts in the composition of employment toward high wage jobs increases wages throughout the economy. Beaudry, P., D.A. Green & B. Sand, 2007. "Spill-Overs from Good Jobs," NBER Working Papers 13006. 17 ECONorthwest The Traded Sector in Portlandʼs Regional Economy 23 Growth in traded sector incomes may lead to increases in the cost of living One common side effect of growing employment and income is growth local prices, particularly housing prices.18 More people and more income increase the demand for housing in a region, and, unless supply responds proportionally, housing prices will rise. Figure 12 shows the correlation between growth in traded sector incomes and housing prices (as measured by the Federal Housing Finance Agency’s housing price index). Figure 12. Change in HUD OFHEO Housing Price Index vs. Change in Traded Real Mean Wages, 1980-2010 OFHEO Index 300 250 200 150 Portland 100 50 0 $0 $20 $40 $60 $80 $100 $120 Thousands Real Mean Traded Sector Income Source: IPUMS USA; ECONorthwest analysis of U.S. Census and American Community Survey data. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Growth in the traded sector may increase funds for local public services – particularly for education. As described above, growth in the traded sector raises average incomes, spending and property values. As such, a growing traded sector likely increases state and local tax revenues. Some debate whether the increase in tax revenues is sufficient to offset the higher local public service costs that accompany a growing Roback, J. 1982. “Wages, Rents, and Quality of Life.” Journal of Political Economy 90(6):1257-1278.; Gleaser, E. and J. Gottleib, 2009. “The Wealth of Cities: Agglomeration Economies and Spatial Equilibrium in the United States.” Journal of Economic Literature 47(4): 983-1028. 18 ECONorthwest The Traded Sector in Portlandʼs Regional Economy 24 local economy. However, some recent evidence suggests that a growing traded sector increases revenues by amount sufficient to offset rising costs and that per pupil spending on education increases. Economists Michael Greenstone and Enrico Moretti compare communities that won large new plants (aka million dollar plants) to the communities that were also finalists to get these plants.19 They find that winning increases incomes in the industry and property values (similar to the effects described above). They also find “modest evidence” that attracting a large new manufacturing facility boosts spending on local public goods – particularly education. The growth and industry mix in the traded sector may affect the formation and growth of new/small businesses in the region. In general, new (typically small) businesses are responsible for most net job creation within an economy.20 Thus, unsurprisingly, regions with more small businesses experience faster job growth. Between 1977 and 2000 a 10 percent increase in the number of firms per worker was associated with a 9 percent increase in employment growth.21 Thus, the traded sector may affect regional economies by creating (or hindering ) the conditions that allow entrepreneurs to thrive. Economists argue that entrepreneurs are more likely to create new/small businesses in an area when: • • • • • Local market for their goods or services is large Inputs are easily available to new businesses (e.g., venture capital, specialized workers, independent input suppliers) The area facilitates the generation and transmission of new ideas Entrepreneurs are supported by the local culture and political environment Certain natural advantages exist.22 The traded sector may affect each of these areas. Greenstone, M and E. Moretti, 2004. “Bidding for Industrial Plants: Does Winning a `Million Dollar Plant’ Increase Welfare?” NBER Working Paper 9844. 19 Haltiwanger, John .C.; Jarmin, Ron C.; and Miranda, Javier, 2010. "Who Creates Jobs? Small vs. Large vs. Young." NBER Working Paper 16300. 20 21 Gleaser, E.L., W. Kerr, and G. Ponzetto, 2010. “Clusters of Entrepreneurship.” NBER Working Paper 15377. Glaeser, E.L. & Rosenthal, S. S. & Strange, W.C., 2010. "Urban economics and entrepreneurship," Journal of Urban Economics, 67(1): 1-14. 22 ECONorthwest The Traded Sector in Portlandʼs Regional Economy 25 First, as described above, growth in the traded sector increases the employment in local markets. Employment growth in local markets stems, in part, from entrepreneurs starting new businesses to profit from the growth in the local market. A larger population with more money means that an entrepreneur is more likely to find success starting a new business because demand is higher (which allows entrepreneurs to benefit from larger scale economies). Second, the availability of inputs is partially a function of traded sector characteristics. If key industries in a region’s traded sector are vertically integrated (i.e., firms in the industry own most of the pieces of the supply chain), the available supply of various inputs in the local market will be thin. This makes starting a new business less attractive. Alternatively, if the traded sector facilitates the creation of high quality input markets (e.g., it attracts ample skilled workers or encourages the creation of ample, independent suppliers), it makes starting a new business in the area more attractive. Third, to the extent that traded sector industries invest in research and development or to the extent that they attract smart, innovative people, traded sector industries make it more likely that a local entrepreneur will have a new, breakthrough idea that supports the creation of new firms and the growth of new or existing industries. Fourth, to the extent that the traded sector helps to foster a culture of entrepreneurs, it may facilitate the growth of small businesses. For instance, the entrepreneurial culture in Silicon Valley tolerated failure – e.g., investors in Silicon Valley allowed entrepreneurs to fail without blackballing them in the future.23 Finally, particular natural advantages make regions attractive to entrepreneurs in the industries dependent on those advantages. Furthermore, particular natural advantages may facilitate the creation of an entrepreneurial culture. For instance, some attribute part of NYC’s entrepreneurial culture to the city’s great 19th century port which attracted large numbers of entrepreneurs to the region (because the advantages of locating near ports at that time were large).24 In sum, growth in the traded sector increases the size of the local market and creates the space for new local sector entrepreneurs to create new businesses and flourish. The effect of the traded sector on new traded sector firms is more ambiguous. If a region’s traded sector supports a robust market of competitive, independent input suppliers, promotes the creation and dissemination of new Saxanian, A., 1994. Regional Advantage: Culture and Competition in Silicon Valley and Route 128. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press; Glaeser, Rosenthal, and Strange (2010) 23 24 Glaeser, Rosenthal, and Strange (2010) ECONorthwest The Traded Sector in Portlandʼs Regional Economy 26 ideas, or fosters a culture of entrepreneurs, it may promote entrepreneurial activity in the traded sector as well. This may or may not occur. Cities like New York and Boston have managed to invent and reinvent their local economies several times and industries came and went.25 However, in other cities (e.g., Pittsburgh and Detroit) large scale industries dominated and failed to create the conditions in which new entrepreneurs could flourish.26 In general, Portland performs well on measures of entrepreneurs. Relative to other large cities, the average establishment size in Portland is below average (14 workers per establishment versus the US metro average of 15.5).27 The rate of new business creation in Oregon is also close to the US average. Between 20092011, 32 out of every 10,000 adult Oregonians started a new business. This is close to the overall US average of 33 new businesses per 10,000 adults, but Oregon’s rate of new business creation has fallen relative to 1999-2001 (when the rate was 39 per 10,000 and Oregon had one of the highest rates in the country).28 These facts suggest that Portland’s rates of entrepreneurship are ok (and by extension that Portland’s traded sector is not stifling new business creation); however, the decline in new business creation over the past decade is worth keeping an eye on. Glaeser, E.L., 2011. Triumph of the City. Tantor Media.; Chinitz, B., 1961. “Contrasts in Agglomeration: New York and Pittsburgh”, American Economic Review 51(2): 279-289. 25 26 Glaeser (2011) , Chinitz (1961) ECONorthwest analysis of 2009 County Business Patterns Metro area file. We limit the sample of metro areas to the 272 areas with employment greater than 50,000. 27 28 Fairlie, R., 2012. “Kauffman Index of Entrepreneurial Activity, 1992-2011.” www.kauffman.org/kiea ECONorthwest The Traded Sector in Portlandʼs Regional Economy 27 VI. WHY DOES INDUSTRY MIX AND HEALTH OF THE TRADED SECTOR VARY ACROSS REGIONS? In previous sections, we have documented that: • • • the composition of the traded sector changes over time the composition and performance of the traded sector varies across place the performance of the local economy is strongly tied to the performance of the traded sector. However, one important question remains – why does the industry mix and performance of a region’s traded sector (and thus the regional economy overall) vary across time and place? The traded sector includes a diverse set of industries, so answering this question is difficult. Some traded sector industries require certain natural resources, so they locate in regions that offer particular natural advantages (e.g., proximity to natural resources like oil or good soil).29 Other traded sector industries need access to certain markets, so they locate near transportation hubs (e.g., ports, airports, rail and road hubs).30 Still other traded sector industries require access to key people or ideas, so they grow up around particular individuals or groups (who are frequently tied to university or their hometowns).31 In general, traded sector industries seek out locations that allow them to achieve high productivity at low cost, and a wide variety of factors affect regional costs and productivity. 32 Understanding regional costs and productivity differentials (as well as overall regional economic health) starts with an assessment of capacity and utilization. Capacity is what the economy could produce—the potential. Utilization is degree to which the economy employs its capacity—the actual. For instance, an influx to a region of the working-age people with engineering degrees increases capacity; the expansion of a firm that hires a lot of engineers increases utilization. Glaeser, E.L. and W. Kerr, 2009. “Local Industrial Conditions and Entrepreneurship: How Much of the Spatial Distribution Can We Explain?," Journal of Economics & Management Strategy,. 18(3): 623-663. 29 30 O’Sullivan, A.. 2009. Urban Economics 7e. McGraw-Hill/Irwin. Klepper (2010); Zucker, L.G, and M.R. Darby, 2007. "Star Scientists, Innovation and Regional and National Immigration," NBER Working Papers 13547; Hausman, N., 2011. “University Innovation, Local Economic Growth, and Entrepreneurship.” Unpublished Manuscript. 31 Glaeser and Kerr (2007), Moretti, E., 2011. “Local Labor Markets.” In Handbook of Labor Economics Volume 4b. Elsiver. 32 ECONorthwest The Traded Sector in Portlandʼs Regional Economy 28 Ultimately, long-run economic growth reflects changes in capacity, and short-run fluctuations reflect changes in utilization. A region derives its capacity from innovation and the four forms of capital: human capital (people and their skills), natural capital (climate, natural resources, ecosystem services), physical capital (machines, roads, buildings), and social capital (institutions and social norms). When capacity increases productivity increases (and costs may fall). Global economic conditions, entrepreneurial activity, and governance shape how well a regional economy uses its capacity. However, as utilization changes market forces will lead costs to adjust. E.g., in a growing region with high utilization, resources are scare so prices/costs increase. Alternatively, in a region with excess capacity (or low utilization), prices will fall. Changing prices will provoke a response. High (low) wages will attract (repel) workers or lead firms to leave (come) until prices settle into a new equilibrium. Traded-sector firms can increase regional economic capacity by: • Attracting skilled workers and other forms of mobile capital that add to regional capacity. • Providing knowledge and complementary inputs that increase the productivity of existing capacity. • Investing directly in productive facilities (e.g., buildings or other infrastructure). • Investing in research and development which supports the growth of existing industries and may prompt cross-over innovation in other industries that create spin-off companies and the attraction/growth of new traded sector industries.33 • Supporting the local sector, including paying—directly or indirectly through employees—taxes to state and local governments that can be used to invest in local economic capacity (e.g., public infrastructure, education, or restoration of natural capital). Regional economic capacity is not solely a function of the traded sector. The local sector plays an important role in affecting regional economic capacity, utilization, and the health of the traded sector. For instance, if the local construction industry or local land use and building regulators are inefficient, the cost of building new houses, factories, or office buildings will increase, decreasing regional traded sector competitiveness. If local school systems or health care systems are subpar (e.g., low quality output at high cost), the quality Duranton (2007) provides a nice summary of this process which is further confirmed by Kerr, W., 2010. “Breakthrough Innovations and Migrating Clusters of Innovations” Journal of Urban Economics. 67(1): 46-60. 33 ECONorthwest The Traded Sector in Portlandʼs Regional Economy 29 of the local workforce will suffer and costs will increase, decreasing regional traded sector competitiveness. If a region offers low quality restaurants or other cultural amenities, regional quality of life suffers and firms must pay higher wages to attract workers, decreasing regional traded sector competitiveness.34 Ultimately, Wilbur Thompson effectively summarized the combination of traded and local sector activities that promote the economic capacity required to maintain a healthy traded sector over the long run when he said: “... [A]ll products wax and wane, and so the long-range viability of any area must rest ultimately on its capacity to invent and/or innovate or otherwise acquire new export bases. The economic base of the larger metropolitan area is, then, the creativity of its universities and research parks, the sophistication of its engineering firms and financial institutions, the persuasiveness of its public relations and advertising agencies, the flexibility of its transportation networks and utility systems, and all the other dimensions of infrastructure that facilitate the quick and orderly transfer from old dying bases to new growing ones.” Roback (1982), Albouy, D., 2008. “Are Big Cities Bad Places to Live? Estimating Quality of Life Across Metropolitan Areas.” NBER Working Paper 14472. 34 ECONorthwest The Traded Sector in Portlandʼs Regional Economy 30 APPENDIX A. RAW HISTORICAL DATA FOR FIGURES 3-8 Table A-1. Raw Historical Data for Figures 3-8 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 Percent Change in Traded Goods Employment since 1970 USA Metros 0% 39% 13% 19% -3% Portland, OR 0% 31% 32% 53% 40% Seattle, WA 0% 22% 38% 23% 25% Minneapolis, MN 0% 24% 14% 22% 16% Denver, CO 0% 77% 50% 36% 34% Sacramento, CA 0% 50% 84% 96% 55% Cincinnati, OH 0% 5% -30% -30% -44% St. Louis, MO 0% -2% -16% -26% -45% Percent Change in Traded Goods Mean Wages since 1970 USA Metros 0% -7% 8% 22% 26% Portland, OR 0% 8% 20% 52% 60% Seattle, WA 0% -8% 2% 21% 38% Minneapolis, MN 0% -2% 19% 34% 45% Denver, CO 0% 2% 17% 37% 56% Sacramento, CA 0% -1% 21% 65% 74% Cincinnati, OH 0% -2% 15% 38% 42% St. Louis, MO 0% 1% 19% 28% 35% Percent Change in Traded Services Employment since 1970 USA Metros 0% 51% 109% 171% 187% Portland, OR 0% 48% 92% 185% 206% Seattle, WA 0% 53% 113% 205% 239% Minneapolis, MN 0% 36% 94% 164% 170% Denver, CO 0% 62% 120% 215% 226% Sacramento, CA 0% 40% 146% 177% 203% Cincinnati, OH 0% 29% 45% 89% 73% St. Louis, MO 0% 17% 49% 82% 89% Percent Change in Traded Services Mean Wages since 1970 USA Metros 0% -11% 7% 29% 30% Portland, OR 0% -7% 7% 30% 29% ECONorthwest The Traded Sector in Portlandʼs Regional Economy A-1 Seattle, WA 0% -7% 9% 45% 53% Minneapolis, MN 0% -4% 14% 43% 48% Denver, CO 0% -4% 9% 44% 45% Sacramento, CA 0% -15% 1% 18% 17% Cincinnati, OH 0% -9% 10% 32% 31% St. Louis, MO 0% -10% 7% 27% 27% Percent Change in Local Employment since 1970 USA Metros 0% 72% 101% 152% 179% Portland, OR 0% 54% 83% 134% 159% Seattle, WA 0% 40% 83% 119% 137% Minneapolis, MN 0% 47% 68% 114% 129% Denver, CO 0% 62% 90% 134% 168% Sacramento, CA 0% 70% 160% 177% 210% Cincinnati, OH 0% 32% 36% 67% 72% St. Louis, MO 0% 32% 48% 74% 84% Percent Change in Local Mean Wages since 1970 USA Metros 0% -11% 3% 15% 13% Portland, OR 0% -11% -3% 14% 12% Seattle, WA 0% -3% 6% 23% 20% Minneapolis, MN 0% -11% 4% 21% 19% Denver, CO 0% 0% 7% 25% 23% Sacramento, CA 0% -10% 6% 21% 21% Cincinnati, OH 0% -6% 2% 18% 15% St. Louis, MO 0% -12% -3% 10% 9% ECONorthwest The Traded Sector in Portlandʼs Regional Economy A-2