HENRik IBSEN AND THE THEATRE CONVENTiONS

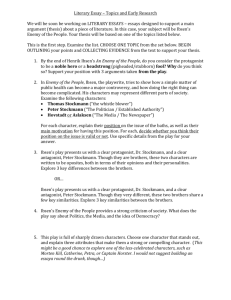

advertisement