Hematocrit Determination: Lab Procedure & Objectives

advertisement

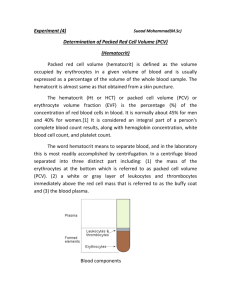

HEMATOCRIT DETERMINATION OBJECTIVES: Upon completion of this laboratory exercise and future practice and discussion, the student will be given the opportunity to demonstrate the ability to: (1) define "hematocrit" verbally and mathematically; (2) describe the evolution of the measurement of the hematocrit; (3) explain the significance of the hematocrit in terms of its use in diagnosis and treatment; (4) describe the specimen requirements for the test; (5) compare and contrast the manual hematocrit with the automated hematocrit; (6) describe the procedure for performance of the microhematocrit; (7) identify sources of error; (8) formulate mechanisms for resolution of problems encountered in performing the microhematocrit; (9) explain the maintenance and calibration of a microhematocrit centrifuge; (10) perform the microhematocrit procedure, without references, and achieve results within 2% of the predetermined value; (11) explain the use of the microhematocrit as a quality control device; (12) given a set of data, correlate the microhematocrit to the hemoglobin and red cell count and identify any discrepancies; (13) state the normal ranges for the hematocrit. PRINCIPLE: The microhematocrit determination is based on the principle that if a sample of whole (anticoagulated) blood is centrifuged for a period of time and at a speed to achieve maximum packing of the cells, the height of the red cell column divided by the height of the column of cells and plasma represents the total volume of whole blood that is occupied by the erythrocytes. In older conventional units, this number was multiplied by 100 and the hematocrit expressed as a per cent. In SI units the hematocrit is expressed as the decimal fraction of the division with the unit L/L. DISCUSSION: Dorland's Medical Dictionary defines "hematocrit" as the "volume percentage of erythrocytes in whole blood". It is well established that if whole (anticoagulated) blood is allowed to stand undisturbed, the red cells will eventually settle to the bottom of the tube. In the manual hematocrit determination the settling process is hastened by centrifuging a tube of blood. The most commonly used manual method for the hematocrit determination today, involves the use of a capillary tube into which the blood is collected. This capillary tube of blood is then centrifuged for approximately 2500g for a calibrated length of time to achieve maximum packing of the cells. The hematocrit is then determined by using some type of reading device which allows the tech to directly read the hematocrit as a percent. This method is considered to be one of the simplest and most accurate and reproducible laboratory tests. An older method for determination of the hematocrit involved the use of the Wintrobe tube that we now use for the ESR. This method required much more blood and the tube had to be spun for approximately 30 minutes to achieve maximum packing of the cells. Most hematocrits today are determined on automated systems and are calculated from other directly measured parameters. SPECIMEN: EDTA anticoagulated whole blood or capillary blood collected into heparinized capillary tubes. EQUIPMENT: Capillary tubes, nonheparinized (blue tip) Capillary tubes, heparinized (red tip) Sealing clay Microhematocrit centrifuge Microhematocrit reading device PROCEDURE: (1) Obtain a blood sample by one of the methods below: a. Perform a fingerstick and collect two heparinized (red tip) capillary tubes, filling each about _ - ¾ full. Make sure to mix the tubes by gently tilting the tubes back and forth several times. This allows the blood to come in contact with the heparin coating the sides of the tube. b. Perform a venipuncture and collect and EDTA sample. After thoroughly mixing the sample, fill two plain (blue tip) capillary tubes about _ - ¾ full with blood. (NOTE: the instructor will demonstrate the easiest way to fill the tubes without spilling blood.) (2) Make sure that the exterior of the capillary tubes are free of blood by wiping the exterior with gauze or a KimWipe. (3) Seal one end of each capillary tube. To do this, place a finger over one end of the capillary tube then gently press the opposite end of the tube into the clay. Twist the tube in the clay and remove. If you are using the yellow clay sealant, one insertion into the clay is sufficient. If you are using the white sealant, insert the end of the tube into the sealant twice to make sure you get a good seal. It is best to place the dry end of the tube into the sealant - this will help prevent contamination of the sealant with blood. CAUTION: When you are pressing the tube into the clay, make sure that you do not press down with the finger you have over the end of the tube - this will help prevent a nasty cut, since these tubes are rather fragile and will snap if enough pressure is exerted. (4) Place the sealed capillary tube in a groove of the head of the microhematocrit centrifuge with the sealed end toward the outside of the head and in contact with the rubber gasket. Balance the centrifuge by placing the second capillary tube in the groove opposite the first; if you have several hemato- crits to perform you may put the duplicate tubes side-by-side and balance these tubes with duplicates from another patient. Note the number corresponding to the groove. (5) Place the centrifuge head cover on the centrifuge head and screw the cover down until just finger tight. (6) Put the hinged cover down and lock. (7) Set the timer for 5 minutes. (8) As soon as the centrifuge stops, open the hinged cover and remove the head cover and remove the capillary tubes. (9) Use one of the reading devices provided. This laboratory has three different types of reading devices and the instructions for their use on written on them. (10) Results of the two tubes should agree within 2% of each other. If they do not, repeat the above procedure. SOURCES OF ERROR: (1) Hemolyzed sample may give falsely decreased results and should not be used. (2) Blood must be well-mixed and should be at room temperature before testing. (3) The capillary tube must be adequately sealed prior to centrifugation. If it is not, the result will be falsely low because as the tube is centrifuged, red cells will escape around the defect in the seal. (4) The time and speed of centrifugation are important factors in obtaining maximum packing of the red cells. The speed of the microhematocrit centrifuges is preset, so the spinning time is the only adjustable variable. Maximum packing time for each centrifuge should be determined on a regular basis and is considered a part of the quality control in the hematology area. Inadequate centrifugation will result in falsely elevated results due to excessive trapped plasma. Calibration of the microhematocrit centrifuge for determination of maximal packing time is fairly easy. Several pairs of capillary tubes are filled from the same patient sample. Each pair is then centrifuged for a different time, starting with a minimum time and increasing the time until the cells will pack no further. (5) The blood:anticoagulant ratio is particularly important, especially when using EDTA. Excessive EDTA will cause a falsely decreased hematocrit due to shrinkage of the red blood cells. Liquid anticoagulants, such as sodium citrate and heparin may cause falsely decreased hematocrits when the proper blood:anticoagulant ratio is not maintained by dilution of the sample. (6) Falsely increased hematocrits may be reported if the buffy coat is included in the reading of the height of the red cell column. The buffy coat, which is comprised of white cells and platelets, is usually a very thin whitish layer above the red cells that can be observed when the blood is centrifuged. In disease states where the white count is excessively elevated, inclusion of the buffy coat can cause a significant error. (7) Failure to read the hematocrit within 10 minutes after the centrifuge stops will result in redispersion of the red cells in the plasma and a slanting of the red cell/plasma interface, causing a falsely elevated reading. (8) Even when the hematocrit is properly centrifuged there remains a small amount of plasma in trapped in the red cell column. When comparing manual hematocrits from an automated instrument, which does not have trapped plasma, the manual result is usually about 1 - 2% higher. NOTES: The determination of the microhematocrit is not only a significant diagnostic measurement, but is also of some importance as a check on the validity of other hematological data. In blood containing red cells of normal size and shape the hemoglobin and RBC count correlate with the hematocrit. The correlation between these three values is called or termed "The Rules of Three" and they are as follows: Hgb x 3 = Hct ± 3% (in other words, a Hgb of 12 g/dl would correspond to a Hct of 33 - 39%) 3 x RBC ≈ Hb Other useful correlations include the following: 1% Hct = 0.34 g/dl Hb 1% Hct = 107,000 red cells/cu.mm (in other words, the red cell count should be approximately 100,000 times the hematocrit value). CAUTION: These estimated values are never reported, but can be used to "spot-check" results to determine if all data fit together properly. Visual observation of the hematocrit can yield other information about the patient. For example, patients with increased platelet or white counts will have a large, and usually very visible, buffy coat. Hyperbilirubinemia, hemolysis or lipemia can be observed in the plasma layer in the tube. Bilirubin imparts a distinct yellow color to the plasma (NOTE: plasma with this coloration is referred to as icteric); hemolysis will produce a pink or red colored plasma; and, lipemia will produce a plasma with a milky appearance. NORMAL RANGES: refer to your text hct.pro