'manor' nowadays is almost certain to conjure up

advertisement

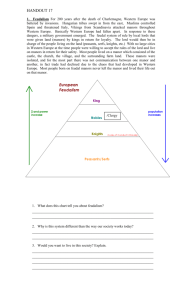

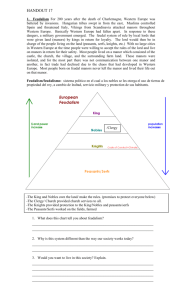

HISTORICAL NOTES THE MANORS OF CRICK - 1 Introduction The mention of the word 'manor' nowadays is almost certain to conjure up a picture of an old-world house, either timber-framed or stone-built and dating from the 16th or 17th centuries, in the setting of an attractive and long-established garden. Even if not the largest house, it would without doubt be the most important in the village, and the owner might still carry the title of the Lord of the Manor. How, then, is this conception to be reconciled with the situation in Crick, where there are two such houses, and a third which was until recently a farm-house, all known as 'manors'? This is to say nothing of two or three others, which at one time brought the total up to five or six. Such a multiplicity of manors was by no means unique to this village, and indeed it was very common. For instance, among the nearby villages, Winwick had three. West Haddon had four, and Yelvertoft five manors, and cases existed of even more. This state of things seems even more complicated if one reads the manorial history of such a village as set out for example in the great 'History of Northamptonshire by Bridges, or in the later book by Baker. A 'manor' was obviously something more than just a house and garden, and an account of the history of the 'manors' of Crick, to be clear and understandable, cannot be presented without firstly making an attempt to define what is meant by the work 'manor’, and to describe manors and the manorial system in England. Moreover, since the origins of the Crick manors can be traced beyond the Norman Conquest into the AngloSaxon period and even earlier to Roman times, there must be included some account of the historical background. To begin at the time of William I, the Normans brought the word 'manor’ in its French form of 'manoir' or the Latin 'manerium1 into England. The word originally signified a habitation, but in the Domesday Book, that great survey of his new realm made by William in 1086, it was at times used indiscriminately as an alternative to the term 'terra', meaning land, for the same piece of property. Put simply, a 'manor1 was a tract of territory; we might say an estate, which was managed from a single local administrative centre as an economic unit with its own jurisdiction. This definition has to be couched in such general terms without giving a more specific meaning because so diverse were the types of manor and its organisation and structure, that there was in reality no typical or normal example. For generations, historians have sought such a model manor to use as a basis for definition, but by general consensus this approach had to be abandoned. Only through recognising the wide range of diversity among manors has this more general definition been evolved. The Norman invaders were careful in many ways to adapt their new ideas onto existing English customs and systems as they found them, and the network of manors, which they laid down, used as a basis the existing and ancient pattern of land-holdings within a network of villages and hamlets. In barely half of the cases, however, did manor and village coincide, and this, the simplest type included Crick at the time of the Domesday Inquest, except for a reservation which will be looked at later, but it was not long before this single manor became divided. There were many situations where a particular manor took in only part of a village, the rest belonging to one or more other manors, as in those places nearby already mentioned. In nearly as many other examples, manors encompassed several villages, usually adjacent, but sometimes separate. Obviously there was a great variation in size; the largest manors contained 1200 acres and over; those in the middle range covered from 600 to 1200 acres, and the smaller ones had from 600 down to only tens of acres. Not only did manors vary in size and in their relation to villages, but there was an almost infinite diversity in their internal structure and organisation. The one constant factor was that all land was held of the king. When William I established his government over the conquered English, he continued their system of land tenure in which the grant of land was made by the Icing in the first place, and if it was given up for any reason, the land reverted to his hands. William's military commanders and soldiers who had been instrumental in subduing and supervising the country were found frequent reward in the form of grants of land, in return for which military service was required of them. There were approximately two classes of men concerned; those nearest to the king and the most influential, the kings 'men’, whom we may call barons; and subordinates and nominees of the barons, the baron's 'men1, which can be classified in a general way as knights, the fighting men. There was personal relationship here, the knights swearing fealty to the barons who in turn owed loyalty to the king, and the granting of land amongst them served as a cement to these loyalties. Vast areas made up of land all over the country were parceled out to the barons, but not before William had taken his share, some 17% of the total. In all, there were about 170 barons, some great, some of minor importance, and they held between them 49% of the country, the largest individual share of 3% being granted to the king's half-brother Robert de Mortain. Most of what was left was granted to monasteries and high churchmen, in accordance with the established Anglo-Saxon practice. Barons and the ecclesiastical establishments were known as 'tenants-in-chief' since they held their possessions directly of the king, their chief. The tenants-in-chief, barons as well as ecclesiastics then let out their territories to knights, whose portions consisted generally of groups of manors. The manors could thus be regarded as cells, which together went to make up the body of landed structure of which the kingdom was composed. A knight's share could range from a single manor to as many as fifty, but those more 1 generously endowed with numerous manors sub-let them singly or in groups to their 'men', lower in the social order. They in their turn could sub-sub-let, but whoever held a manor at whatever level did so in return for military service to the man by whom the letting was made, and so ultimately to the king. The allocation taken by the king was called the Royal Demesne, whilst the territories granted to the dozen greatest barons were called ‘honours’ and those of the lesser barons became generally known as 'baronies'. The possessions of the knights were called ‘knight’s’ fees’, and one such fee could include as many as a dozen manors or more. He who held a manor in return for military service was 'lord of the manor', or "lord of the soil", a title used in Crick up to the 18th century. In the course of the 12th century these military obligations, especially at manorial level, began to be commuted to money payments, which contributed towards the hire of mercenary soldiery, until in the course of time the physical nature of the commitment all but disappeared. Where a knight or his tenant held only one manor, he would be found as a rule living there in what we now call the 'manor house', but which at the time was usually referred to as the "hall1 (Latin 'aula'). This was his seat of administration from whence the manor was managed and where his family resided. In many cases of one tenant having lordship over a number of manors, his residence was on one of the manors, and he or his bailiff made visits to the others once or twice a year. Alternatively, the lord might install as bailiff or reeve on each manor, to live in the hall if one existed, to ensure closer supervision of the affairs of that manor. Most, but not all, manors contained a proportion of land, usually about a third, to be farmed directly for the lord, and known as 'demesne' or lord's land. The remainder was worked by the peasantry (a word meaning countrymen) for their own subsistence. They fell into three broad classes. The most numerous were the villeins or village men, who held their portion of land in return for labour services on his demesne. They were obliged to work on certain specified days every week in the lord's service, and on every day at particular seasons of the year. This left their own tillage to be done as and when they could. The villein was tied to his land by tenure which was 'at the lord's will', being as a rule only for life, so that on the death of a villein the land reverted to the lord, to be re-allocated by him as he chose. The most prosperous class consisted of the freemen who held their land mostly free of obligatory services to the lord, although of course they paid rent. A freeman could come and go much as he pleased, and was able to sell his tenure and buy another, although the ownership still resided in the lord's hands. Most importantly, unlike villein tenure, freehold tenure passed automatically 'in tail' from father to son. This inheritable tenure, known in law as 'fee simple' formed the basis for our modern system of freehold. The third class consisted of bordars and cottars, whom we might call cottagers. Their landholding was small, usually only a few acres for their own use and rented from the lord. They had far fewer labour obligations than the villeins so that they were free to hire themselves out as labourer’s whereever needed. They comprised a class of farm laborers, who through the lack of land ties could transfer their services to other manors, and even move residence provided there was consent by the lord. All three groups were subject to a variety of customary payments both in money and in kind, payable to the lord, and being of considerable antiquity were so deeply rooted that some survived almost to the present day. The annual Wroth Silver payment to the Duke of Buccleugh at Knightlow Hill in Warwickshire is an example, which is, in fact, still being made today. Not only was there a great variety in numbers and classes of the peasantry from manor to manor, but the proportions of demesne, villein and freehold land fluctuated over wide limits. On some manors there was a large amount of villein land, with much less or even a lack of freehold land; others had most freehold, and there were frequent examples of manors with no demesne land at all. It is important to realise that almost all arable land was held in strips intermixed over the whole parish, whether it was demesne, freehold or villein land, and where a village was divided among two or more manors, there was no separation of land between them. It was all governed by the open-field system, and the only separated properties were the home-closes attached to the manorial halls. This gives some idea of the great variety to be found in types of manor, their size, population and organisation. Such a variety was not deliberately imposed by the Normans but was already there, having developed gradually through an earlier and long period of history. Starting from the Domesday Book, we can today follow the course of further changes and variations until the feudal system itself became the casualty of that change, to be replaced by our present industrial society. E. W. Timmins Copied by J Goodger in 2005 from Crick News Spring1979 2