WRITING ABOUT LITERATURE IN THE MEDIA AGE

advertisement

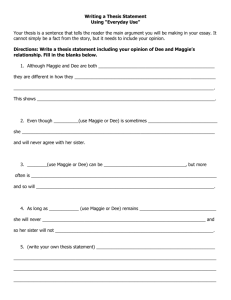

WRITING ABOUT LITERATURE IN THE MEDIA AGE © 2005 Daniel Anderson 0-321-121202-9 Exam Copy ISBN 0-321-19835-2 Bookstore ISBN Visit www.ablongman.com/replocator to contact your local Allyn & Bacon/Longman representative. s a m p l e c h a p t e r The pages of this Sample Chapter may have slight variations in final published form. Longman 1185 Avenue of the Americas 25th floor NewYork, NY 10036 www.ablongman.com 5 Argument and the Rhetorical Situation People generally quarrel because they cannot argue. —Gilbert K. Chesterton Argument might seem too strong a term for the writing that we do in most college classes. Arguments are verbal battles, drawn-out conflicts between people who will never see eye-to-eye. Right? Some disagreements do devolve into heated confrontations, but the arguments we engage in our academic writing are more like the debates that take place in a court of law than the quarrels we might encounter over dinner. In an academic argument, the parties must present a well-reasoned case that convinces others that their position has merit. We argue our points intuitively all the time. In a class discussion we might claim that the setting of a story creates a desolate atmosphere. (We would probably provide reasons and discuss examples to support our position.) In the hallway we might debate the merits of a tough class. (We might weigh the pros and cons of the workload in terms of the learning benefits, accommodating alternative possibilities.) We might try to convince a friend to rent a film we want to see; we would consider the tastes of our friend (assessing our audience) and tailor our argument to appeal to those tastes. We can think of these examples as unique rhetorical situations. In these situations, we use elements of argument, though we might not realize it. CONSIDERING OUR RHETORICAL SITUATION Our purpose and audience determine the way we approach any writing task. These elements derive from our rhetorical situation (our task, our readers, and the context in which we write). We sometimes compose formal papers. We might write letters home, or letters to a newspaper editor or potential employer. We participate in all kinds of writing situations, and each demands a unique approach. Writing for college presents a particular kind of rhetorical situation. Our purpose when we compose a formal academic argument will be to convince others that our thesis is worth considering, that it has merit. But we will also work from a number of smaller goals as we compose. We will have the goal of establishing our authority as we write. Our purpose in the body of our argument might be to use evidence as carefully and compellingly as possible. We might seek to defuse opposing points of view as our argument evolves. All of these purposes will determine how we approach the tasks we undertake when writing an argument. 133 134 Chapter 5 Argument and the Rhetorical Situation An academic audience also shapes our use of language. If we are writing for our peers or instructor in a classroom setting, we will generally maintain an appropriate level of formality and adhere to the rules of standard American English. We should avoid slang or other non-standard language, write correct and complete sentences, and eliminate mechanical errors. We should also know that academic readers generally value organization, coherency, and fair-minded arguments. Understanding that we are writing in an academic rhetorical situation can help us assess our audience and refine our purpose as we compose. EXPLORING ACADEMIC ARGUMENTS To compose academic arguments, we must have an approach that lends itself to an argument. That is, our interpretations must entertain alternative possibilities and allow us to pursue open-ended questions about a work. This complexity will ensure that we have an arguable topic. We must then convince our readers that we can be trusted, by establishing our authority to speak on the subject. We should articulate our topic with a thesis, and then lay out a series of convincing reasons for accepting our approach. We must also entertain opposing points of view and either accommodate or refute them in our own argument. Finally, we must provide solid evidence that illustrates and supports the points that we make along the way. Of course, when we read and write about literature, we cannot simply follow a formula in lockstep fashion. Because literature appeals to our emotions as well as our intellect, we must use argument to help us develop and express our interpretations. Argument is not simply about proving a point; it is about exploring an idea or issue that matters to us. Arguments will evolve organically as we draft them (see Chapter 6), but eventually they will help us explain what we discover as clearly as we can. To get a sense for how academic arguments can promote this kind of process of inquiry we will examine a short story by Alice Walker called “Everyday Use.” ALICE WALKER Alice Walker (born in 1944) grew up in a home with eight children in rural Eatonton, Georgia. Her parents were sharecroppers. In 1952 at age eight she was accidentally shot in the eye with a BB fired by one of her brothers. The injury resulted in a scar that discolored her eye. She was tormented by the scar and by the reactions of schoolmates until at age fourteen she underwent surgery and had the scar removed. By the time she graduated high school she was elected the most popular in her class. She went on to study at Sarah Lawrence college and published her first collection of poems, Once, shortly after graduating. Walker’s work includes poetry, short stories, novels, and essays. Her writing has been praised for its treatment of difficult subjects related to race, family, and poverty and for its honest, emotional, and lyrical qualities. She is perhaps best known for her Pulitzer Prize winning novel, The Color Purple. “Everyday Use” was first published in 1973. Exploring Academic Arguments 135 Everyday Use For Your Grandmama 1 5 I will wait for her in the yard that Maggie and I made so clean and wavy yesterday afternoon. A yard like this is more comfortable than most people know. It is not just a yard. It is like an extended living room. When the hard clay is Backswept clean as a floor and the fine sand around the edges lined with tiny, irreg- ground ular grooves, anyone can come and sit and look up into the elm tree and wait formaterial underfor the breezes that never come inside the house. standing Maggie will be nervous until after her sister goes: she will stand hopeless- “Everyday Use” ly in corners, homely and ashamed of the burn scars down her arms and legs, eyeing her sister with a mixture of envy and awe. She thinks her sister has held life always in the palm of one hand, that “no” is a word the world never learned to say to her. You’ve no doubt seen those TV shows where the child who has “made it” is confronted, as a surprise, by her own mother and father, tottering in weakly from backstage. (A pleasant surprise, of course: What would they do if parent and child came on the show only to curse out and insult each other?) On TV mother and child embrace and smile into each other’s faces. Sometimes the mother and father weep, the child wraps them in her arms and leans across the table to tell how she would not have made it without their help. I have seen these programs. Sometimes I dream a dream in which Dee and I are suddenly brought together on a TV program of this sort. Out of a dark and soft-seated limousine I am ushered into a bright room filled with many people. There I meet a smiling, gray, sporty man like Johnny Carson who shakes my hand and tells me what a fine girl I have. Then we are on the stage and Dee is embracing me with tears in her eyes. She pins on my dress a large orchid, even though she has told me once that she thinks orchids are tacky flowers. In real life I am a large, big-boned woman with rough, man-working hands. In the winter I wear flannel nightgowns to bed and overalls during the day. I can kill and clean a hog as mercilessly as a man. My fat keeps me hot in zero weather. I can work outside all day, breaking ice to get water for washing; I can eat pork liver cooked over the open fire minutes after it comes steaming from the hog. One winter I knocked a bull calf straight in the brain between the eyes with a sledge hammer and had the meat hung up to chill before nightfall. But of course all this does not show on television. I am the way my daughter would want me to be: a hundred pounds lighter, my skin like an uncooked barley pancake. My hair glistens in the hot bright lights. Johnny Carson has much to do to keep up with my quick and witty tongue. But that is a mistake. I know even before I wake up. Who ever knew a Johnson with a quick tongue? Who can even imagine me looking a strange white man in the eye? It seems to me I have talked to them always with one foot raised in flight, with my head turned in whichever way is farthest from them. Dee, though. She would always look anyone in the eye. Hesitation was no part of her nature. 136 10 15 Chapter 5 Argument and the Rhetorical Situation “How do I look, Mama?” Maggie says, showing just enough of her thin body enveloped in pink skirt and red blouse for me to know she’s there, almost hidden by the door. “Come out into the yard,” I say. Have you ever seen a lame animal, perhaps a dog run over by some careless person rich enough to own a car, sidle up to someone who is ignorant enough to be kind to him? That is the way my Maggie walks. She has been like this, chin on chest, eyes on ground, feet in shuffle, ever since the fire that burned the other house to the ground. Dee is lighter than Maggie, with nicer hair and a fuller figure. She’s a woman now, though sometimes I forget. How long ago was it that the other house burned? Ten, twelve years? Sometimes I can still hear the flames and feel Maggie’s arms sticking to me, her hair smoking and her dress falling off her in little black papery flakes. Her eyes seemed stretched open, blazed open by the flames reflected in them. And Dee. I see her standing off under the sweet gum tree she used to dig gum out of; a look of concentration on her face as she watched the last dingy gray board of the house fall in toward the red-hot brick chimney. Why don’t you do a dance around the ashes? I’d wanted to ask her. She had hated the house that much. I used to think she hated Maggie, too. But that was before we raised the money, the church and me, to send her to Augusta to school. She used to read to us without pity; forcing words, lies, other folks’ habits, whole lives upon us two, sitting trapped and ignorant underneath her voice. She washed us in a river of make-believe, burned us with a lot of knowledge we didn’t necessarily need to know. Pressed us to her with the serious way she read, to shove us away at just the moment, like dimwits, we seemed about to understand. Dee wanted nice things. A yellow organdy dress to wear to her graduation from high school; black pumps to match a green suit she’d made from an old suit somebody gave me. She was determined to stare down any disaster in her efforts. Her eyelids would not flicker for minutes at a time. Often I fought off the temptation to shake her. At sixteen she had a style of her own: and knew what style was. I never had an education myself. After second grade the school was closed down. Don’t ask me why: in 1927 colored asked fewer questions than they do now. Sometimes Maggie reads to me. She stumbles along good-naturedly but can’t see well. She knows she is not bright. Like good looks and money, quickness passed her by. She will marry John Thomas (who has mossy teeth in an earnest face) and then I’ll be free to sit here and I guess just sing church songs to myself. Although I never was a good singer. Never could carry a tune. I was always better at a man’s job. I used to love to milk till I was hooked in the side in ’49. Cows are soothing and slow and don’t bother you, unless you try to milk them the wrong way. I have deliberately turned my back on the house. It is three rooms, just like the one that burned, except the roof is tin; they don’t make shingle roofs any more. There are no real windows, just some holes cut in the sides, like the portholes in a ship, but not round and not square, with rawhide holding the shutters up on the outside. This house is in a pasture, too, like the other one. No doubt when Dee sees it she will want to tear it down. She wrote me once that no matter where we “choose” to live, she will manage to come see us. But she will never bring her friends. Maggie and I thought about this and Maggie asked me, “Mama, when did Dee ever have any friends?” Exploring Academic Arguments 137 She had a few. Furtive boys in pink shirts hanging about on washday after school. Nervous girls who never laughed. Impressed with her they worshiped the well-turned phrase, the cute shape, the scalding humor that erupted like bubbles in lye. She read to them. 20 25 When she was courting Jimmy T she didn’t have much time to pay to us, but turned all her faultfinding power on him. He flew to marry a cheap city girl from a family of ignorant flashy people. She hardly had time to recompose herself. When she comes I will meet—but there they are! Maggie attempts to make a dash for the house, in her shuffling way, but I stay her with my hand. “Come back here,” I say. And she stops and tries to dig a well in the sand with her toe. It is hard to see them clearly through the strong sun. But even the first glimpse of leg out of the car tells me it is Dee. Her feet were always neatlooking, as if God himself had shaped them with a certain style. From the other side of the car comes a short, stocky man. Hair is all over his head a foot long and hanging from his chin like a kinky mule tail. I hear Maggie suck in her breath. “Uhnnnh,” is what it sounds like. Like when you see the wriggling end of a snake just in front of your foot on the road. “Uhnnnh.” Dee next. A dress down to the ground, in this hot weather. A dress so loud it hurts my eyes. There are yellows and oranges enough to throw back the light of the sun. I feel my whole face warming from the heat waves it throws out. Earrings, too, gold, and hanging down to her shoulders. Bracelets dangling and making noises when she moves her arm up to shake the folds of the dress out of her armpits. The dress is loose and flows, and as she walks closer, I like it. I hear Maggie go “Uhnnnh” again. It is her sister’s hair. It stands straight up like the wool on a sheep. It is black as night and around the edges are two long pigtails that rope about like small lizards disappearing behind her ears. “Wa-su-zo-Tean-o!” she says, coming on in that gliding way the dress makes her move. The short stocky fellow with the hair to his navel is all grinning and he follows up with “Asalamalakim,* my mother and sister!” He moves to hug Maggie but she falls back, right up against the back of my chair. I feel her trembling there and when I look up I see the perspiration falling off her chin. “Don’t get up,” says Dee. Since I am stout it takes something of a push. You can see me trying to move a second or two before I make it. She turns, showing white heels through her sandals, and goes back to the car. Out she peeks next with a Polaroid. She stoops down quickly and lines up picture after picture of me sitting there in front of the house with Maggie cowering behind me. She never takes a shot without making sure the house is included. When a cow comes nibbling around the edge of the yard she snaps it and me and Maggie and the house. Then she puts the Polaroid in the back seat of the car, and comes up and kisses me on the forehead. Meanwhile Asalamalakim is going through motions with Maggie’s hand. Maggie’s hand is as limp as a fish, and probably as cold, despite the sweat, and she keeps trying to pull it back. It looks like Asalamalakim wants to shake hands but wants to do it fancy. Or maybe he don’t know how people shake hands. Anyhow, he soon gives up on Maggie. “Well,” I say. “Dee.” *Arabic greeting meaning “Peace be with you” used by members of the Islamic faith. 138 30 35 40 45 Chapter 5 Argument and the Rhetorical Situation “No, Mama,” she says. “Not ‘Dee,’ Wangero Leewanika Kemanjo!” “What happened to ‘Dee’?” I wanted to know. “She’s dead,” Wangero said. “I couldn’t bear it any longer, being named after the people who oppress me.” “You know as well as me you was named after your aunt Dicie,” I said. Dicie is my sister. She named Dee. We called her “Big Dee” after Dee was born. “But who was she named after?” asked Wangero. “I guess after Grandma Dee,” I said. “And who was she named after?” asked Wangero. “Her mother,” I said, and saw Wangero was getting tired. “That’s about as far back as I can trace it,” I said. Though, in fact, I probably could have carried it back beyond the Civil War through the branches. “Well,” said Asalamalakim, “there you are.” “Uhnnnd,” I heard Maggie say. “There I was not,” I said, “before ‘Dicie’ cropped up in our family, so why should I try to trace it that far back?” He just stood there grinning, looking down on me like somebody inspecting a Model A car. Every once in a while he and Wangero sent eye signals over my head. “How do you pronounce this name?” I asked. “You don’t have to call me by it if you don’t want to,” said Wangero. “Why shouldn’t I?” I asked. “If that’s what you want us to call you, we’ll call you.” “I know it might sound awkward at first,” said Wangero. “I’ll get used to it,” I said. “Ream it out again.” Well, soon we got the name out of the way. Asalamalakim had a name twice as long and three times as hard. After I tripped over it two or three times he told me to just call him Hakim-a-barber. I wanted to ask him was he a barber, but I didn’t really think he was, so I didn’t ask. “You must belong to those beef-cattle peoples down the road,” I said. They said “Asalamalakim” when they met you, too, but they didn’t shake hands. Always too busy: feeding the cattle, fixing the fences, putting up salt-lick shelters, throwing down hay. When the white folks poisoned some of the herd the men stayed up all night with rifles in their hands. I walked a mile and a half just to see the sight. Hakim-a-barber said, “I accept some of their doctrines, but farming and raising cattle is not my style.” (They didn’t tell me, and I didn’t ask, whether Wangero (Dee) had really gone and married him.) We sat down to eat and right away he said he didn’t eat collards and pork was unclean. Wangero, though, went on through the chitlins and corn bread, the greens and everything else. She talked a blue streak over the sweet potatoes. Everything delighted her. Even the fact that we still used the benches her daddy made for the table when we couldn’t afford to buy chairs. “Oh, Mama!” she cried. Then turned to Hakim-a-barber. “I never knew how lovely these benches are. You can feel the rump prints,” she said, running her hands underneath her and along the bench. Then she gave a sigh and her hand closed over Grandma Dee’s butter dish. “That’s it!” she said. “I knew there was something I wanted to ask you if I could have.” She jumped up from the table and went over in the corner where the churn stood, the milk in it clabber by now. She looked at the churn and looked at it. “This churn top is what I need,” she said. “Didn’t Uncle Buddy whittle it out of a tree you all used to have?” Exploring Academic Arguments 50 55 60 65 139 “Yes,” I said. “Uh huh,” she said happily. “And I want the dasher, too.” “Uncle Buddy whittle that, too?” asked the barber. Dee (Wangero) looked up at me. “Aunt Dee’s first husband whittled the dash,” said Maggie so low you almost couldn’t hear her. “His name was Henry, but they called him Stash.” “Maggie’s brain is like an elephant’s,” Wangero said, laughing. “I can use the churn top as a center-piece for the alcove table,” she said, sliding a plate over the churn, “and I’ll think of something artistic to do with the dasher.” When she finished wrapping the dasher the handle stuck out. I took it for a moment in my hands. You didn’t even have to look close to see where hands pushing the dasher up and down to make butter had left a kind of sink in the wood. In fact, there were a lot of small sinks; you could see where thumbs and fingers had sunk into the wood. It was beautiful light yellow wood, from a tree that grew in the yard where Big Dee and Stash had lived. After dinner Dee (Wangero) went to the trunk at the foot of my bed and started rifling through it. Maggie hung back in the kitchen over the dishpan. Out came Wangero with two quilts. They had been pieced by Grandma Dee and then Big Dee and me had hung them on the quilt frames on the front porch and quilted them. One was in the Lone Star pattern. The other was Walk Around the Mountain. In both of them were scraps of dresses Grandma Dee had worn fifty and more years ago. Bits and pieces of Grandpa Jarrell’s Paisley shirts. And one teeny faded blue piece, about the size of a penny matchbox, that was from Great Grandpa Ezra’s uniform that he wore in the Civil War. “Mama,” Wangero said sweet as a bird. “Can I have these old quilts?” I heard something fall in the kitchen, and a minute later the kitchen door slammed. “Why don’t you take one or two of the others?” I asked. “These old things was just done by me and Big Dee from some tops your grandma pieced before she died.” “No,” said Wangero. “I don’t want those. They are stitched around the borders by machine.” “That’ll make them last better,” I said. “That’s not the point,” said Wangero. “These are all pieces of dresses Grandma used to wear. She did all this stitching by hand. Imagine!” She held the quilts securely in her arms, stroking them. “Some of the pieces, like those lavender ones, come from old clothes her mother handed down to her,” I said, moving up to touch the quilts. Dee (Wangero) moved back just enough so that I couldn’t reach the quilts. They already belonged to her. “Imagine!” she breathed again, clutching them closely to her bosom. “The truth is,” I said, “I promised to give them quilts to Maggie, for when she marries John Thomas.” She gasped like a bee had stung her. “Maggie can’t appreciate these quilts!” she said. “She’d probably be backward enough to put them to everyday use.” “I reckon she would,” I said. “God knows I been saving ’em for long enough with nobody using ’em. I hope she will!” I didn’t want to bring up how I had offered Dee (Wangero) a quilt when she went away to college. Then she had told me they were old-fashioned, out of style. 140 70 75 80 Chapter 5 Argument and the Rhetorical Situation “But they’re priceless!” she was saying now, furiously; for she has a temper. “Maggie would put them on the bed and in five years they’d be in rags. Less than that!” “She can always make some more,” I said. “Maggie knows how to quilt.” Dee (Wangero) looked at me with hatred. “You just will not understand. The point is these quilts, these quilts!” “Well,” I said, stumped. “What would you do with them?” “Hang them,” she said. As if that was the only thing you could do with quilts. Maggie by now was standing in the door. I could almost hear the sound her feet made as they scraped over each other. “She can have them, Mama,” she said, like somebody used to never winning anything, or having anything reserved for her. “I can ’member Grandma Dee without the quilts.” I looked at her hard. She had filled her bottom lip with checkerberry snuff and it gave her face a kind of dopey, hangdog look. It was Grandma Dee and Big Dee who taught her how to quilt herself. She stood there with her scarred hands hidden in the folds of her skirt. She looked at her sister with something like fear but she wasn’t mad at her. This was Maggie’s portion. This was the way she knew God to work. When I looked at her like that something hit me in the top of my head and ran down to the soles of my feet. Just like when I’m in church and the spirit of God touches me and I get happy and shout. I did something I never had done before: hugged Maggie to me, then dragged her on into the room, snatched the quilts out of Miss Wangero’s hands and dumped them into Maggie’s lap. Maggie just sat there on my bed with her mouth open. “Take one or two of the others,” I said to Dee. But she turned without a word and went out to Hakim-a-barber. “You just don’t understand,” she said, as Maggie and I came out to the car. “What don’t I understand?” I wanted to know. “Your heritage,” she said. And then she turned to Maggie, kissed her, and said, “You ought to try to make something of yourself, too, Maggie. It’s really a new day for us. But from the way you and Mama still live you’d never know it.” She put on some sunglasses that hid everything above the tip of her nose and her chin. Maggie smiled; maybe at the sunglasses. But a real smile, not scared. After we watched the car dust settle I asked Maggie to bring me a dip of snuff. And then the two of us sat there just enjoying, until it was time to go in the house and go to bed. INQUIRING FURTHER 1. What is your position on Mrs. Johnson’s decision to give the quilts to Maggie? Do you think Mrs. Johnson made the right decision at the end of the story? Why or why not? 2. For a minute, entertain the opposite position. Can you think of reasons why someone might disagree with your perspective on Mrs. Johnson’s decision? 3. What assumptions might someone who disagreed with your position on Mrs. Johnson’s decision have? What beliefs would prompt them to disagree with you? 4. What assumptions underlie your own position on Mrs. Johnson’s decision? What beliefs prompt you to feel the way you do? Exploring Academic Arguments 141 Finding an Arguable Topic Arguments are based on disagreement, so your approach must have some complexity if it is to serve as a topic for an argument. Suggesting that Maggie is the most likeable character in Alice Walker’s “Everyday Use” would constitute more of an opinion than an argument. Similarly, claiming that Hakim-a-barber represents an outsider in “Everyday Use” would not provide many avenues for discussion—what is there to argue about? However, a claim like heritage limits opportunities in “Everyday Use” might make a good topic for an argument, allowing a writer to explore the positive and negative aspects of tradition in the story with some complexity. To write an argument, you must look past the obvious to find an angle that illuminates and acknowledges the many facets of a work. Instead of saying that Maggie is the most likeable character, you might argue that the narrator’s choice at the end to give the quilts to Maggie emphasizes family over African traditions. To make this argument, you would need to address conflicts between family and African traditions. You would need to prepare for objections that might be raised to this perspective—are Mrs. Johnson and Maggie (and the personal traditions they represent) really presented entirely favorably? Are the traditions of the Johnson family different from those of Africa? Topics that can be challenged lend themselves to arguments because they require writers to justify their way of thinking and to support that justification with credible evidence. Initially, these multi-faceted topics might seem to be more work than a simple “yes or no” discussion of the story. However, as you explore you will see how anticipating alternative possibilities and responding to them with your own explanations will give you more to write about and make your essay stronger in the long run. ■ C H E C K L I S T FOR FINDING AN ARGUABLE TOPIC ■ Avoid topics that suggest something obvious about the story or something that resembles a factual statement. Facts provide little room for argument. ■ Steer clear of topics that resemble opinions. Refine your impressions and opinions into interpretations based on the evidence in the work. ■ Choose topics that can be challenged or that challenge alternative approaches. Where there is mutual agreement, even about a theme, character, or message, there is little room for argument. ■ Anticipate objections when selecting a topic. If you can find no objections to your approach, it probably lacks complexity. If you discover overwhelming objections, you may want to rethink your topic. An ideal topic will allow you to acknowledge and respond to legitimate objections as a way of building your own case. ■ Be sure that your topics can be discussed with evidence from the text or with information you might gather through research. A complex and arguable topic will not be of much benefit if you cannot find ample evidence to support it. 142 Chapter 5 Exercise 5.1 Argument and the Rhetorical Situation Identifying Arguable Topics Working with a group of fellow students (or on your own if your instructor prefers), explore potential topics for arguing about “Everyday Use.” Begin by selecting someone to keep track of the group’s work (or preparing to take notes on your own). 1. Consider these topics: ● “Everyday Use” demonstrates the importance of traditions to African Americans. ● Names in “Everyday Use” represent tensions between family heritage and African heritage. ● Quilts symbolize family history in “Everyday Use.” ● “Everyday Use” highlights the dangers of resisting change. ● Family identity is maintained by women in “Everyday Use.” ● Dee is the central character in “Everyday Use.” 2. For each topic, respond to the following prompts: ● First, look at each topic and decide whether you believe it to be an arguable topic. ● If you believe the topic to be arguable, write a sentence or two detailing an alternative position to the one listed in the topic. ● If you do not believe the topic to be arguable, write a revision of the sentence that would make the topic arguable. 3. Develop two additional arguable topics on your own. 4. Look over all of the topics you have been considering. Select from these topics one that you believe would be the most useful for constructing an argument about “Everyday Use.” Write two or three sentences explaining your decision. Establishing Authority as a Writer Others are more likely to accept your arguments if they believe you are knowledgeable, fair-minded, and careful. You can establish this credibility by presenting detailed research and discussion of a work to readers, composing with a reasonable tone that respects alternative perspectives, and maintaining a high standard of correctness in your writing. When it comes to being knowledgeable about your topic, there are no shortcuts. You must invest the time and energy into reading and understanding the work before you can argue about it with authority. Of course, this requires a process of inquiry like the one we have been discussing throughout this book. You can begin thinking and writing about a work right away. However, as the process evolves, you should develop a closeness with the work that prepares you to discuss it in detail. You can also conduct research to help establish your authority (see Chapter 4). Careful attention to detail will help establish your authority. Consider the passage below from an essay on “Everyday Use.” Exploring Academic Arguments 143 Through names, “Everyday Use” illustrates the conflicts between African heritage and family heritage. Ultimately, names in the story privilege the family heritage represented by Mrs. Johnson and Maggie. Initially, Mrs. Johnson refers to her daughter by her given name, “Dee.” When Dee announces that she has changed her name to “Wangero Leewanika Kemanjo,” Mrs. Johnson is willing to consider this African heritage. She refers to her daughter as “Wangero” and tells her, “‘If that’s what you want us to call you, we’ll call you”’ (139). As tensions emerge between the two heritages, the names begin to blur. When referring to Muslim doctrines, Mrs. Johnson combines the names using parentheses: “Wangero (Dee).” As Dee asks about family items like the churn top, Mrs. Johnson again uses parentheses, but this time emphasizes her daughter’s given name: “Dee (Wangero).” As the story concludes, Mrs. Johnson resumes calling her daughter “Dee,” emphasizing how family connections take precedence over African heritage in the story. The writer here shows that she has spent some time thinking about how names relate to family tradition. She has tracked the evolution of names in the story. She also invests the effort in spelling out her points with details that will convince a reader that she is knowledgeable and willing to share her ideas with others. You can also conduct research to help establish your authority. Consider this passage that incorporates ideas culled from two essays on “Everyday Use.” Through names, “Everyday Use” illustrates the conflicts between African heritage and family heritage. As Helga Hoel argues, “[the] names Dee bases her new-found identity on resemble Kikuyu names, but they are all [misspelled] . . . Dee has names representing the whole East African region. Or more likely, she is confused and has only superficial knowledge of Africa and all it stands for” (par 12). This confusion illustrates the tensions between recovering an African heritage and maintaining more recent family connections. As Barbara Christian explains, “during the 1960s Walker criticized the tendency among some African Americans to give up the names their parents gave them—names which embodied the history of their recent Essays on “Everyday Use” 144 Chapter 5 Argument and the Rhetorical Situation past—for African names that did not relate to a single person they knew” (13). Names demonstrate the power of both African and family heritage but the confusion associated with the names Wangero and Hakim-a-barber emphasizes the central role family heritage plays in the story. This writer makes similar points, but uses evidence in the form of quotations from essays to back them up. Referring to these published sources also illustrates that the writer has taken the time to learn about the work. Equally important, these references suggest that the writer’s perspective is informed by the ideas of others, that the writer is fair-minded and willing to entertain interpretations that run counter to her own. You can also establish this sense of fair-mindedness by responding to objections to your argument (discussed below). Finally, both writers carefully present their ideas. They properly cite material they have introduced into their papers. They have revised and edited their writing to make it clear and correct. Taking the time to edit, proofread, and format your papers (see Chapter 8) helps to establish your credibility by showing that you care about your ideas. EXPLORING CLAIMS, REASONS, AND ASSUMPTIONS Argument has a close connection with logic, with thinking that moves from point A, to point B, to point C in an objective and predictable way. Logic can be used to try to “prove” something to be true—a formal argument might be A: All dogs bark; B: Rover is a dog; therefore, C: Rover barks. In this argument, a claim is made: Rover barks. Two reasons are provided to convince us of the claim: All dogs bark; and Rover is a dog. But such proofs are less concrete than they would at first seem. Perhaps there are some dogs that do not bark, or perhaps Rover is a stuffed animal (not really a dog). We can also see the limits of such formal logic by constructing arguments that make no sense: A: All dogs bark; B: Rover is barking; therefore C: Rover is a dog. What if Rover is a seal or a teacher with a bad cough? While this kind of formal logic is limited, it can help us understand something of the process of argument. First, it reveals that we cannot simply make a claim and assume that others will accept it. We must instead provide convincing reasons that will prompt others to believe the claim. Additionally, we must offer evidence that supports those reasons. We can show that Rover is indeed a kind of dog that barks; if we can provide that evidence, then the argument will be more convincing. Further, logic prompts us to consider the assumptions that might be hidden beneath the reasons that ask us to believe something. For instance, the second example (A: All dogs bark; B: Rover is barking; therefore C: Rover is a dog) falls apart because there is an assumption that must be made to get from B to C (the assumption that everything that barks must be a dog). As readers and writers, learning to identify and explore these assumptions makes us critical consumers and producers of arguments. When we write about literature, we can make similar use of formal elements of argument—as long as we understand their limitations and our purpose when composing. We are not out to “prove” the truth of a statement, but to make claims about our understanding and to convince others that our claims are worth believ- Exploring Claims, Reasons, and Assumptions 145 ing. We do this by providing compelling reasons, considering assumptions underlying our positions, and supporting what we say with evidence. We also must remember that literature has an emotional component. Our responses to literature should still appeal to our interests and senses; our explanations of those responses will benefit from the reasoned structures that argument can provide. Our claims should relate to the thesis we wish to explore in our argument. About “Everyday Use,” we might start with a thesis like when Mrs. Johnson gives the quilts to Maggie, she privileges family traditions and identity over African heritage. We could then support that thesis with claims like quilts uniquely represent family identity (claim one), and family identity is based on everyday activities (claim two). These claims, however, cannot stand on their own. Take the claim that quilts uniquely represent family identity. To convince others of the claim, we need to provide supporting reasons that explain why the claim is believable. We might suggest that the fabric used in the quilts symbolizes family history, and the stitching symbolizes connections between generations. We might also explore the assumption beneath these two reasons and our claim. We can agree that fabric symbolizes family history and that stitching connects generations, but what makes this a unique representation? Beneath our claim is an assumption that quilts are unique in representing family identity. We might explain this assumption by suggesting that the arrangement of stitched fabric within the quilts tells a story, giving them a unique way of presenting family identity. We can represent the structure that our argument is taking by listing the thesis, claim, supporting reasons, and assumptions: Thesis: when Mrs. Johnson gives the quilts to Maggie, she privileges family traditions and identity over African heritage Claim: quilts uniquely represent family identity Reason: the fabric used in the quilts symbolizes family history Reason: the stitching symbolizes connections between generations Assumption: the arrangement of stitched fabric within the quilts tells a story in a unique way Like an outline, the components of our argument can guide us as we draft the body of our paper. Additionally, by considering their relationships with our thesis, we can be assured that the claims, reasons, and assumptions we discuss will Tutorial for understanding help to convince our audience of the value of our overall approach. arguments Exercise 5.2 Supporting a Claim Working with a group of fellow students (or on your own if your instructor prefers), develop a list of reasons and explore assumptions to support a claim. Begin by selecting a person to keep track of the group’s work (or preparing to take notes on your own). 1. First, consider the claim that everyday activities represent shared traditions. (You can also develop a claim of your own based on your understanding of “Everyday Use.”) 2. Consider reasons that might support this claim. List the most significant reason as a sentence. 146 Chapter 5 Argument and the Rhetorical Situation 3. Think of another reason that follows from or supports the first reason that you have listed. Write a sentence that states your second reason. 4. Inquire into the assumptions that lie beneath the reasons you have stated above. An assumption might connect the reasons to one another or to the claim you are investigating. Once you have discovered an assumption that supports your reasons and claim, write a sentence that lists the assumption as a statement. PROVIDING EVIDENCE Evidence supports the claims and reasons we present in our argument. When writing about literature, evidence primarily comes in the form of examples from works we are discussing, quotations from other readers, or references to contextual information that illuminates the work. Evidence from Works Evidence from works should be directly related to the statements we seek to support. In supporting our statement that the fabric used in the quilts symbolizes family history we might cite the passage listing the pieces of fabric used in the quilt: In both of them were scraps of dresses Grandma Dee had worn fifty and more years ago. Bits and pieces of Grandpa Jarrell’s Paisley shirts. And one teeny faded blue piece, about the size of a penny matchbox, that was from Great Grandpa Ezra’s uniform that he wore in the Civil War. (139) This citation provides compelling evidence to support our statement that the fabric pieces symbolize family history. If we wanted to bolster our point about stitching, however, we would need to find a more relevant example. We also need to discuss carefully evidence that we use. If we cited the passage stating that “It was Grandma Dee and Big Dee who taught [Maggie] how to quilt herself” we would need to explain how the example relates to our point that the stitching represents connections between generations—we cannot assume that the example itself makes our point for us. We could also point out that Dee refuses the other quilts because they are “stitched around the borders by machine” and that Dee explains “these are all pieces of dresses Grandma used to wear. She did all this stitching by hand. Imagine!” In selecting quotations we need to be thorough and precise. We must also be careful and fair. In the last example, for instance, the stitching Dee refers to is part of the dresses that are pieced into the quilt, rather than the stitches that hold the pieces of the quilt together. This is a subtle point, but to be fair we should explain that Dee identifies hand stitching in the scraps of dresses, not in the quilt. We can still claim that the threads that tie those pieces into the quilt connect generations, but this connection comes through a second act of stitching. Evidence from Others We can also support an argument by citing what others have said about a work. Again, we must ensure that our use of this evidence is both relevant and fair. For instance, an essay exploring the role of quilts in Alice Walker’s The Color Purple might be relevant for our argument, but we would need to show our readers the Providing Evidence 147 relationship between the two works and not imply that a quotation about one could simply be applied to the other. We would also need to provide detailed discussion of the evidence that we integrate into our argument—consider using at least twice as much of your own words and explanations as those of others. Additionally, when using others as sources of evidence, we must evaluate those sources, looking for potential credibility problems. An article in an online journal found through a library Web site carries a high level of authority based on its source. Tutorial An essay found on a paper mill Web site carries little or no authority. In between for these two extremes lies a range of sources that may provide strong evidence for evaluating sources our arguments. Avoid articles that do not consider the complexities of a topic or that fail to cite additional sources to support the claims that they make. Also, look for more than one source of information as you integrate the ideas of others into your arguments. You can spot biases and problems with credibility by conducting enough research to allow you to balance and compare the sources you use. (For more on finding and evaluating sources, see Chapter 4.) Contextual Evidence Historical or biographical information about an author can also bolster an argument. Concerning “Everyday Use,” for instance, we might discover that Alice Walker has traveled to Africa where she received an African name, or that Walker has written about quilts and about African-American identity. We could also investigate some of the cultural movements represented in “Everyday Use.” We could discover historical parallels that shed light on the characters of Dee and Hakim-a-barber (and Mrs. Johnson and Maggie). We could learn about movements during the 1960s to recover African heritage or to collect and display artifacts that preserve cultural identity. All of this contextual information can be found through research. Again, we must evaluate the credibility of this background information. Further, we must be careful not to let contextual evidence over-determine our interpretations of the story. Biographical information about Walker, for instance, can illuminate the characters, but it does not allow us to claim that the story depicts Walker’s experience or that Walker thinks or feels a certain way. “Everyday Use” remains a story about the Johnsons and about themes of family and identity (among others). Locating compelling contextual information that illuminates those themes is not the same as saying the story is about that evidence. (For more on relating literature to its contexts, see Chapter 13.) ■ C H E C K L I S T FOR USING EVIDENCE ■ Draw carefully upon the work you are discussing for evidence. Even if your argument relies on the interpretations of others or contextual information, you must connect your statements with the work itself and find support in the work for the points you make. ■ Learn to be a successful researcher to discover the best evidence for your arguments. Understand the benefits and skills of library research and learn to locate resources available on the Internet. Make informed judgments about the sources you discover in the library and on the Internet. ■ Select the most relevant evidence for your argument. Use passages from works that support your claims. Select research sources that speak 148 ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Chapter 5 Argument and the Rhetorical Situation directly to the works or topics you are arguing about. Spell out missing connections between the evidence you use and the statements you make. Treat evidence fairly. Be diligent in your reading of evidence and do not jump to conclusions about how evidence supports your points. Further, be sure not to ignore counter-evidence that can potentially undermine your argument. Discuss the evidence you use. Compose approximately twice as much text in your own words for every instance when you integrate evidence into your argument. Explain the significance of the evidence and discuss connections with your thesis, claims, and reasons. Integrate the evidence you use smoothly into the text of your argument. Compose introductory tags that demonstrate where the evidence comes from. Watch out for plagiarism. Use quotation and citation methods carefully to distinguish your evidence from your own writing. (See pages 000-00 for more on avoiding plagiarism and pages 000-000 for more on integrating quotations into your work.) Evaluate the evidence that you use. Consider the source and authority of your evidence. Look for biases within sources and consult a range of sources to fully understand the reliability of your evidence. Do not allow contextual evidence (or the interpretations of others) to over-determine your argument. Learn to consider critically the relationships between history, biography, and literature (see Chapter 13). ADDRESSING OPPOSING POINTS OF VIEW In an argument, we build a case point-by-point by stating a claim and then providing reasons and evidence to support that claim. Objections can be raised to our claims, the reasons that support our claims, and our evidence (as well as to any underlying assumptions beneath our claims and reasons). Additionally, people might disagree with our thesis as a whole. For our arguments to be convincing, we must address these possible objections head on by anticipating, rebutting, and accommodating opposing points of view. Anticipating Opposing Points of View As we compose arguments, we should determine where objections to our points are likely to arise. We can begin by considering our audience and the kinds of assumptions they hold. If we are making a statement about family, does it rely on a set of unique beliefs or is it something that most people are likely to agree about? How can we characterize our audience, and based on this characterization, which of our claims, reasons, and evidence is likely to be challenged by our audience? We can also work through an outline of our argument as a way of anticipating potential objections. We could develop an argument around the claim that family identity is based on everyday activities and perhaps support the claim by showing how everyday activities bring family members together and create shared knowledge. We could sketch out a list of our reasons and assumptions as a way of anticipating objections to our argument: Addressing Opposing Points of View 149 Claim: family identity is based on everyday activities Possible objection: the disputed quilts are not really everyday items Reason: everyday activities bring individuals together Evidence: quilting Possible objection: not all everyday activities bring connections— Dee’s reading to the family is an exception Reason: common experiences create shared knowledge Evidence: benches and other worn items Possible objection: familiar items go unnoticed by family Assumption: shared knowledge creates family identity Evidence: outsider status of Hakim-a-barber Possible objection: outside forces also influence family identity This outline does not represent a comprehensive list of ways we might argue that family identity is based on everyday activities, nor does it cover every objection. It does, however, help us anticipate possible objections so that we will be better able to rebut or accommodate them as we draft our argument. Rebutting Opposing Points of View Anticipating objections is only half the battle. To argue successfully, we must also address those objections directly in our writing. One strategy is to take issue with an objection or with the reasons or evidence that might support that objection. For instance, a possible objection to our claim that everyday activities bring family members together might be that when Dee reads to Maggie and Mrs. Johnson it really pushes the family further apart. We can refute this objection by pointing out that Dee’s reading does not qualify as an everyday activity—it takes place apart from the daily work of the household and does not span generations like the other activities of the story. Composing our rebuttal prompts us to think through these issues and refines our argument. In some cases we might directly challenge the opposing point of view—especially if we are working with the interpretations of others with whom we disagree. We might say that, arguments suggesting that shared activities do not create a connection between individuals fail to recognize the nature of the activities taking place. When activities involve a shared sense of work and span several generations, they do indeed inspire a sense of connection between family members. We could also write a rebuttal that defuses the possible objection without challenging the opposing point of view directly. We could say Although not every activity brings the individuals of the family together, those that involve the daily maintenance of the household and that span several generations have a unique way of bonding individuals. Such a refined statement shows that we are willing to entertain opposing points of view, but that we have focused our argument on the specific claims we want to make. 150 Chapter 5 Argument and the Rhetorical Situation Accommodating Opposing Points of View We need not refute every possible objection to our argument. In fact, were we to do so, our readers would likely find our approach one-sided and unconvincing. We can accommodate (acknowledge and concede to) smaller objections as we make our points. For instance, we might concede that outside forces shape identity, as is evidenced by Dee’s relationship with the family—in fact, it would be hard to argue against the claim. But acknowledging the role of outside forces need not negate our claim about family identity. We can argue that family identity is still shaped by shared knowledge, while we accept that individuals are also shaped by their external circumstances. Accommodation also comes into play when we consider objections to our thesis as a whole. To our suggestion that when Mrs. Johnson gives the quilts to Maggie, she privileges family traditions over African heritage, one might respond that Mrs. Johnson is really acting to change the family traditions with this gesture—if Mrs. Johnson were to keep with the old identity and traditions, she would allow Dee to take the quilts, rather than choosing to give them to Maggie. Because literature allows for more than one viable interpretation, we must advocate for our position while acknowledging those points of view that offer worthwhile alternatives. Here we might acknowledge the moment of change that takes place at the end of the story but suggest that the decision (while representing a change) results in keeping the quilts at the Johnson home and therefore carries more force in its emphasis on the family tradition. However, objections and alternative interpretations can also demand that we change our approach (something we will learn more about as we study the writing process in the next chapters). It might be that we need to go back and rethink our interpretation in terms of this moment of growth. We might compose a new thesis that says, when Mrs. Johnson gives the quilts to Maggie, she highlights the importance of growth and change in maintaining family traditions and identity. We would then find ourselves developing a new set of claims and reasons that could be used to argue the importance of change—we might look at Maggie’s stature in the family, levels of change in Dee and Mrs. Johnson, or instances of positive or negative change. Fully accommodating this new perspective will take some work; however, if the objection is significant, our argument and our understanding of the story will both be made stronger by responding to the alternative possibility. ■ C H E C K L I S T FOR RESPONDING TO OBJECTIONS ■ Anticipate opposing points of view as you plan and draft your arguments. Consider any specific claims, reasons, or evidence that you provide, and then ask how each of these might be questioned. Also imagine objections to your thesis as a whole. ■ Assess the audience for your argument. Consider the values they are likely to hold and how those values might influence their reception of your argument. Determine how claims, reasons, and evidence can be adjusted to appeal to the audience. ■ Create an outline that lists the major claims, reasons, and evidence you will use in your argument. For each item, note possible objections. Sketch out possible responses you might offer to any objections you uncover. ■ Rebut objections that unreasonably undermine your argument. Refute these objections concretely if you are placing your position in Addressing Opposing Points of View 151 direct opposition to another. Defuse these objections if you can, to dismiss them and focus on the core of your own position. ■ Accommodate objections that do not undermine your own position. Show relationships when opposing positions are able to coexist. Concede points that are solid when they do not completely undercut your own position. ■ Rethink your thesis when needed. Maintain a posture of inquiry as you consider objections. When opposing perspectives demand a change in approach, adjust your argument to address these alternatives. Exercise 5.3 Responding to Objections Working with a group of fellow students (or on your own if your instructor prefers), respond to the following claims about “Everyday Use.” Begin by selecting a person to keep track of the group’s work (or preparing to take notes on your own). 1. Consider the following claims: ● The reference to Johnny Carson and other evidence reveals that Mrs. Johnson actually longs for the new identity that Wangero (Dee) represents. ● The quilts do not symbolize everyday use; instead, they are cherished, uncommon items. ● The sudden decision to give the blankets to Maggie is unrealistic. ● Mrs. Johnson, Maggie, and the family culture they represent are portrayed in a negative light. 2. For each claim, assume you are arguing that the story emphasizes family over African traditions, and then respond to the following prompts: ● First, how would you rebut each claim? Is there counter-evidence that can question the claim? Can you show the claim to be unrelated to your position that the story emphasizes family over African traditions? Are there assumptions or reasons needed to support the claim that you might question? Use these considerations, and then write a two or three sentence rebuttal that refutes the claim. ● Next, how would you accommodate the claim? Can the claim stand alongside your own position? If so, how are the two positions related? Does the claim completely undermine your position? If so, can you concede the point while maintaining the integrity of your argument? Use these considerations, then write a two or three sentence statement that accommodates the claim, or write one sentence that revises your position based on the opposing claim. Finally, would it be better to rebut or accommodate the claim? Why? Write two or three sentences explaining your answer. Answer all three of these questions in writing as you refer to the claims above. ●

![Short_Story_Test[1].doc](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008002238_1-7a5ad2a7af6a9cd4f4b95cb6fd0a8215-300x300.png)