La traviata - Minnesota Opera

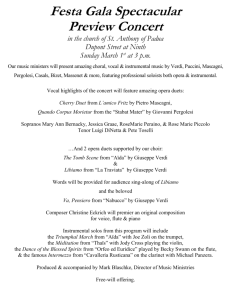

advertisement