Framework for Action - donaldmacpherson.ca

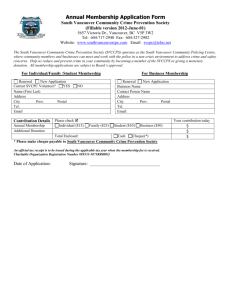

advertisement