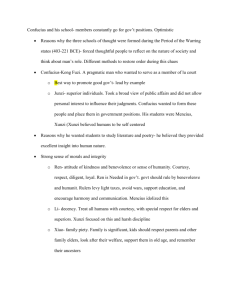

Han Feizi's Criticism of Confucianism and its

advertisement