Theatre Spaces, part 1 Introductory remarks

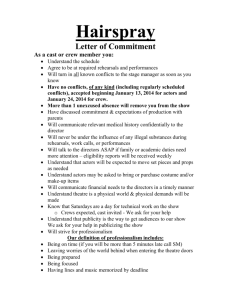

advertisement