Module 1

Introduction to the

Financial Planning

Process

David Mannaioni, CPCU, CLU, ChFC, CFP®

7481

© 1982, 1985, 1991, 1996, 2002–2015, College for Financial Planning, all rights reserved.

This publication may not be duplicated in any way without the express written consent of the publisher. The

information contained herein is for the personal use of the reader and may not be incorporated in any

commercial programs, other books, databases, or any kind of software or any kind of electronic media

including, but not limited to, any type of digital storage mechanism without written consent of the publisher

or authors. Making copies of this material or any portion for any purpose other than your own is a violation

of United States copyright laws.

The College for Financial Planning does not certify individuals to use the CFP, CERTIFIED FINANCIAL

PLANNER™, and CFP (with flame logo)® marks. CFP® certification is granted solely by Certified Financial

Planner Board of Standards Inc. to individuals who, in addition to completing an educational requirement

such as this CFP Board-Registered Program, have met its ethics, experience, and examination requirements.

Certified Financial Planner Board of Standards Inc. owns the certification marks CFP, CERTIFIED

FINANCIAL PLANNER™, and federally registered CFP (with flame logo)®, which it awards to individuals who

successfully complete initial and ongoing certification requirements.

At the College’s discretion, news, updates, and information regarding changes/updates to courses or

programs may be posted to the College’s website at www.cffp.edu, or you may call the Student Services

Center at 1-800-237-9990.

Table of Contents

Welcome ................................................................................... i

How to Study this Material .................................................... iii

Introduction to the Financial Planning Process

& Insurance Course ........................................................... iii

Significance of Learning Objectives .................................. vi

The Learning Process ....................................................... viii

Study Plan/Syllabus ................................................................ 1

Learning Activities ............................................................. 2

Chapter 1: The Financial Planning Process ........................... 5

Critical Skills of Planners ................................................... 6

The Steps of the Process ..................................................... 9

Financial Planning Practice Standards .............................. 11

Chapter 2: Personal Financial Statements ........................... 42

Business Financial Statements vs. Personal Financial

Statements ........................................................................ 43

Financial Statements in Personal Financial Planning ......... 45

Statement of Financial Position ......................................... 45

Cash Flow Statement ........................................................ 53

Chapter 3: The Analysis ....................................................... 58

The Emergency Fund ........................................................ 58

Debt Management ............................................................. 63

Sources of Income ............................................................ 66

Savings and Spending Patterns .......................................... 67

Ratio Analysis .................................................................. 68

Analyzing Sequential Financial Statements ........................ 68

Other Areas of Analysis ..................................................... 70

Chapter 4: Budgeting ............................................................ 72

What is a Budget? .............................................................. 72

Basic Considerations ......................................................... 73

Getting Started .................................................................. 76

Chapter 5: Debt Management ............................................... 89

Consumer Debt .................................................................. 89

Chapter 6: Achieving Special Goals .................................... 106

Step 1: Define Goals in Terms of Dollar Amounts

and Time Frames ............................................................. 106

Step 2: Gather Data to Determine Existing Resources ...... 107

Step 3: Analyze the Issue and Solutions. .......................... 108

Step 4: Develop and Present the Appropriate Vehicles

and Strategies .................................................................. 109

Steps 5 and 6: Implement the Action Plan, and

Schedule and Monitor Results ......................................... 110

Chapter 7: To Lease or Buy ................................................ 111

Types of Leases ............................................................... 111

Considerations in the Lease versus Buy Decision ............. 112

Chapter 8: College Funding ................................................ 116

College Funding Methods ................................................ 117

Investment Vehicles ........................................................ 125

Other Sources of Funds for Education Goals .................... 128

Chapter 9: Special Needs Planning ..................................... 134

Divorce/Remarriage Planning .......................................... 134

Charitable Planning ......................................................... 138

Needs of the Dependent Adult or Disabled Child ............. 138

Terminal Illness Planning ................................................ 139

Closely Held Business Planning ....................................... 140

Summary .............................................................................. 141

Module Review ..................................................................... 143

Questions ......................................................................... 143

Answers ........................................................................... 177

References ............................................................................ 222

About the Author ................................................................. 223

Index ..................................................................................... 224

Welcome

W

elcome to the first course in your journey to become a Certified

Financial Planner certificant. You have chosen a career that will

make a significant positive impact on people’s lives. Helping people

become financially secure brings more than financial rewards to people. Years in

the future, your clients will tell you how it let them accomplish dreams they thought

would be only dreams. They will tell you how it reduced their stress, changed their

marriages, and set future generations on the path to the same success.

You will work hard to earn this designation. The material and expectations are

graduate level. Just like CPAs, you are gaining a profession, not just a designation.

We are committed to helping you achieve this designation and have success in this

profession. Our goal for you is that by the end of this program you will:

1. be successful in passing the CFP Certification Examination and

2. be a competent beginning planner.

There are six courses you will complete:

Financial Planning Process and Insurance

Investment Planning

Income Tax Planning

Retirement Planning & Employee Benefits

Estate Planning

Financial Plan Development

Each of the first five courses have multiple modules, which means volumes of

reading, memorizing, understanding, and applying concepts. This first course has

nine modules. We encourage you to start reading your material prior to attending

i

© 1981, 1991, 1996, 2002–2015, College for Financial Planning, all rights reserved.

the online classes or viewing the recordings. We also encourage you to take the

time during your studies to explore the topic in real life by applying the

knowledge you are learning to your own life. While studying this first module,

pull out your insurance contracts and read them. Meet with your P&C agent and

go through a review of your coverage. You may even want to work with friends,

family, or clients in this area. By experiencing and applying the knowledge in real

life, you will better understand and remember the concepts. Each course offers you

knowledge that has direct application to your life. The last course is entirely different

because you are creating a detailed, comprehensive plan utilizing the knowledge you

have learned.

Once you have completed all the coursework, you will need to do a review.

Research has shown that those testing quickly after their coursework do better on

their exam, so plan your course work with that in mind.

When you complete these courses and accomplish this goal, you will also be

committing to being a lifelong student as the landscape is ever changing. We

hope to have a lifelong relationship with you as a provider of CE and someday

perhaps you will return to gain your master’s degree in financial planning.

Again, congratulations on taking this step. Don’t hesitate to reach out to the

resources at the College if we can help.

David Mannaioni, CPCU, CLU, ChFC, CFP®

Financial Planning Process and Insurance

303-220-4911

David.Mannaioni@cffp.edu

Michael B. Cates, MS, CFP®

Income Tax Planning

303-220-4832

Mike.Cates@cffp.edu

Jason Hovde, CIMA®, CFP®, APMA®

Investment Planning

303-220-4836

Jason.Hovde@cffp.edu

Kristen MacKenzie, MBA, CFP®, CRPC®

Retirement Planning & Employee Benefits

303-220-4826

Kristen.MacKenze@cffp.edu

Kirsten Waldrip, JD

Estate Planning

303-220-4851

Kirsten.Waldrip@cffp.edu

ii

© 1981, 1991, 1996, 2002–2015, College for Financial Planning, all rights reserved.

How to Study this Material

P

lan to invest from 100 to 150 hours of study time for this first course in

the CFP Certification Professional Education Program. If you study at

least 10 hours each week, you should be able to work through the

materials in about 12 weeks. With an additional two weeks for review, you

should be ready to sit for the first exam in about 14 weeks. This means that, on a selfstudy basis, you should be able to complete this course within four to six months.

A number of study plans will work, but the steps outlined below have proven to

be effective.

1. Read the Learning Activities section in the Study Plan/Syllabus chapter to

know which readings match each Learning Objective.

2. There is no supplemental textbook required with this course; all of the course

material is contained in the 10 modules. Write in the answers to the review

questions for each learning objective. If you just read the modules, you will

retain only about 10% of what you read—hardly sufficient to pass the endof-course test. If you physically write in the answers to all the questions, you

will increase your retention by a multiple of four to six times.

3. Read the answers to the review questions and compare your answers to the

approved solutions. If your answers are sufficiently close, move on; if not,

rewrite the correct answer so that you will better remember the correct answer.

Introduction to the Financial Planning

Process and Insurance Course

Imagine that it is five years from today and you are sitting in your office

reviewing the appointments for the next few days. Your first is a client who will

be retiring in just one month. The plan you put together for them has allowed

them to shorten the amount of time it would take to get there. You’ll be

reviewing their cash flow distribution plan for year one. You make a note to

iii

© 1981, 1991, 1996, 2002–2015, College for Financial Planning, all rights reserved.

remind them that they need to send you the information from their employer

about converting the group term insurance before the 30 days expire since the

client has some health problems and to have your assistant send a congratulations

basket to his office the day before retirement.

The next meeting is a prospect who is a referral from one of your favorite clients.

The client was so impressed with how you worked with his estate attorney and

family, he has been telling all his friends. The prospective client expressed

interest in you helping him with his estate plan and investments. You know the

company he works for so you are betting he has significant nonqualified deferred

compensation agreements. You will need to complete some analysis on

managing the deferred compensation and check for concentration issues because

he is retiring in one year. You make a note to tell your assistant to get the new

client folder ready.

The third appointment is going to be a tough one. You advised the clients to purchase

disability coverage but they declined. Now they regret it and are asking for your help

in determining what their new lifestyle will look like since a disability struck. They

aren’t in terrible shape but you have rerun some projections looking at safe

withdrawal rates so you can discuss their new retirement projection. You make a

note to evaluate both annuities and a reverse mortgage line of credit to see whether

those strategies could improve their situation.

You have two investment management reviews (both clients will be very happy),

and a meeting with parents and their grown child to talk about structuring

funding for grandchildren’s education.

The journey to this future starts with a substantial introduction to the basics of

financial planning and insurance analysis. This course will not make the student

an expert in these areas. The most effective professional financial planner is one who

learns to bring the experts together as a team. The modules in this course are:

Introduction to the Financial Planning Process

Regulatory and Ethical Considerations for Financial Planners

iv

© 1981, 1991, 1996, 2002–2015, College for Financial Planning, all rights reserved.

Introduction to the Time Value of Money

Introduction to Risk Management and the Insurance Industry

Introduction to Life Insurance and Annuities

The Life Insurance Selection Process

Health Care

Disability Income and Long-Term Care Insurance

Property and Liability Insurance

Competence in financial planning requires the ability to communicate with the

myriad experts who are needed to put together and implement a client’s financial

plan. Accountants, attorneys, insurance specialists, bankers, investment advisers,

and trust officers are all integral members of the team. Someone has to

coordinate their efforts, and that person is the financial planner. Most financial

planners have one area of expertise because it is virtually impossible to be an

expert in all areas. Most importantly, though, they have a broad understanding of

all the facets of planning so they can provide an integrated approach. The CFP

Certification Professional Education Program will give the student an adequate

understanding of the basics of each area so that he or she can be the leader of the

financial planning team.

Upon successful completion of this course, you will be able to:

explain and initiate the process of personal financial planning

provide competent counsel to individuals regarding their existing risk

management programs and to recognize when the services of a specialist are

required

understand the regulatory, legal, and ethical issues surrounding financial

planning

v

© 1981, 1991, 1996, 2002–2015, College for Financial Planning, all rights reserved.

understand and apply the time value of money concepts and use a financial

function calculator

understand and apply the principles of risk management

identify risk exposures

compare insurance companies and policies and determine the benefits

provided by a given insurance policy

understand the differences among the various forms of insurance

prepare a life insurance needs analysis

understand the history and organization of the insurance industry, the legal

atmosphere in which it operates, and the “language” of insurance

construct and interpret personal financial statements and explain issues

related to personal budgeting

explain different forms of debt and their uses, and the issues involved in the

lease versus buy decision

identify sources and strategies for college funding

explain issues related to special planning needs

Significance of Learning Objectives

Learning objectives, also referred to as LOs, form the foundation of each lesson.

They direct you to the critical components on which you will be evaluated, and

so they are the keys to successful completion of this course.

The learning objectives in this course are organized into three categories that

correspond with three increasingly complex levels of learning. The pyramid

below demonstrates the hierarchy of those levels and their interrelationships.

With the bottom level forming the foundation of the learning pyramid, you can

see how the three levels of learning support build on each other.

vi

© 1981, 1991, 1996, 2002–2015, College for Financial Planning, all rights reserved.

Evaluation

Synthesis

Analysis

Application

Comprehension

Knowledge

Top level learning objectives involve critical thinking by analyzing,

synthesizing, and evaluating information. Example: Analyze a client’s

financial statement to identify strengths and weaknesses.

Middle level learning objectives involve applying knowledge to a specific

task. Example: Construct a personal financial statement that includes a

client’s emergency fund assets.

Bottom level learning objectives involve basic knowledge and

comprehension of information. Example: Identify the financial assets

appropriate for inclusion in a client’s emergency fund.

Each level of learning is accompanied by specific behaviors you are expected to

demonstrate upon mastery of individual learning objectives.

Note: As you progress through this course, keep in mind that most practicing

financial planners conduct their daily business using skills at the higher levels of

learning. The skills developed at the lower levels support those processes by

providing the fundamental building blocks of financial planning activity.

vii

© 1981, 1991, 1996, 2002–2015, College for Financial Planning, all rights reserved.

Study Tips

In the Study Plan/Syllabus chapter of this module, you’ll see a smaller

version of the learning pyramid identifying the level of each learning objective.

As you master each learning objective, you’ll know where it fits in the hierarchy

of learning.

Each learning objective is individually numbered (corresponding with the

module number) for review purposes. In addition, learning objectives are boxed

to make them stand out from the surrounding text. Look for the boxes throughout

each module to guide your studies.

The Learning Process

Learning Activities

In this course, you’ll find three different types of learning activities:

Readings. Since there is a substantial amount of material covered in each of the

modules, it is recommended that you pace yourself, and spread out the readings.

Do not rush through this material. “Cramming” does not work well, and will not

provide you with the preparation you need for both the end-of-course exam and

the CFP® Certification Examination. A steady, methodical approach will enable

you to retain and assimilate more of the material as you work through each of the

modules. It is recommended that you read the material related to the classes that

are recorded BEFORE attending the class or listening to the recording.

Review questions. Through the completion of written problems, you will be able

to demonstrate an understanding of the various financial planning issues in this

course. Review questions have been designed to highlight the relationships

between concepts, and your written responses will reinforce what you have

learned by enabling you to express ideas in your own words. Writing the answers

to the review questions is a critical step in your learning process, since it provides

an opportunity for you to internalize key issues and relationships and it increases

retention by a factor of four to five times. Your responses also provide an

excellent tool for final review prior to the course examination.

viii

© 1981, 1991, 1996, 2002–2015, College for Financial Planning, all rights reserved.

Study Plan/Syllabus

T

he goal of this module is to introduce the financial planning process as

well as some of the basic issues that are often involved in personal

financial planning. These include financial statements, the emergency

fund, debt, budgeting, college funding, the lease versus buy decision, and special

needs planning.

The chapters in this module are:

The Financial Planning Process

Personal Financial Statements

The Analysis

Budgeting

Debt Management

Achieving Special Goals

To Lease or Buy

College Funding

Special Needs Planning

The material in this module focuses on the process of financial planning as well

as some of the basic issues involved in the process.

Study Plan/Syllabus

1

© 1981, 1985, 1996, 2002–2015, College for Financial Planning, all rights reserved.

Upon successful completion of this module, you will be able to describe the

steps of the financial planning process, prepare and interpret basic personal

financial statements, recommend appropriate assets to use for an emergency

fund, analyze a client’s financial situation to identify issues related to

budgeting, discuss debt management and the lease versus buy decision, as

well as recognize special needs planning issues and what to do about them.

To enable you to reach the goal of this module, material is structured around the

following learning objectives:

Learning Activities

Learning Activities

Learning Objective

2

Readings

Module Review

Questions

1–1

Explain the what and

why of the steps in the

financial planning

process.

Module 1, Chapter 1: The

Financial Planning Process

1, 2

1–2

Explain the rationale for

gathering specific

financial information.

Module 1, Chapter 1: The

Financial Planning Process

3–5

1–3

Construct and interpret

personal financial

statements.

Module 1, Chapter 2:

Personal Financial

Statements

6–20

1–4

Recommend assets

appropriate for use in

an emergency fund.

Module 1, Chapter 3: The

Analysis

21–23

1–5

Analyze a client’s

financial situation to

identify issues related to

budgeting.

Module 1, Chapter 4:

Budgeting

24–35

Introduction to the Financial Planning Process

© 1982, 1985, 1991, 1996, 2002–2015, College for Financial Planning, all rights reserved.

Learning Activities

Learning Objective

Module Review

Questions

Readings

1–6

Explain different forms

of debt and their uses.

Module 1, Chapter 5: Debt

Management

36–42

1–7

Explain the issues

involved in the lease

versus buy decision.

Module 1, Chapter 6:

Achieving Special Goals

43, 44

Module 1, Chapter 7: To

Lease or Buy

1–8

Identify sources and

strategies for funding a

college education.

Module 1, Chapter 8:

College Funding

45–50

1–9

Explain issues related to

special planning needs.

Module 1, Chapter 9: Special

Needs Planning

51, 52

Not only must a planner understand the stages of the financial planning process,

he or she must understand what fits into each stage and what does not. You will

be expected to know the critical components of each step and how it relates to the

CFP Board Practice Standards. LO 1-1 focuses on the important aspects of each

of the stages in the financial planning process. There are times when a client is

looking for answers before enough questions have been asked. Being able to

explain the process and reasons why will help keep the client on track. This leads

to proper planning and satisfied clients.

LO 1-2 identifies the basic need to understand why each piece of necessary

information is gathered from the client. Each bit of information helps complete

the picture of where the client is at the beginning of the financial planning

process. Understanding why information is obtained allows a planner to develop

a logical method of asking questions that should gradually give him or her a

nearly complete understanding of the client’s situation.

Study Plan/Syllabus

3

© 1981, 1985, 1996, 2002–2015, College for Financial Planning, all rights reserved.

LO 1-3 focuses not only on the need to understand what a financial statement

says, but also on the need to understand the basis of financial statements well

enough to be able to create them from raw data. The creation of the statement of

financial position and the cash flow statement requires an understanding of what

information is used to develop them. The planner needs this basic understanding

to be able to explain the statements to a client and how the information is used in

the development of the financial plan.

LO 1-4 asks that the student be able to decide which assets are appropriately

placed in an emergency fund. Every client should have an emergency fund in

place; the fund should consist of assets that are readily available for any

unexpected need that arises.

LOs 1-5 and 1-6 deal with the client’s budget and debt management.

Recognizing how cash flow and each asset and liability relates to a client’s

financial condition and being able to analyze how it impacts the client’s ability to

reach established goals is a significant part of the financial planning process.

LO 1-7 introduces the various factors that enter into the lease versus buy

decision-making process.

LOs 1-8 and 1-9 deal with special planning issues. College funding is a common

financial planning need. You will be expected to know the basics of the various

sources of education funding.

4

Introduction to the Financial Planning Process

© 1982, 1985, 1991, 1996, 2002–2015, College for Financial Planning, all rights reserved.

Chapter 1: The Financial Planning

Process

Reading this chapter will enable you to:

1–1

Explain the what and why of the steps in the financial planning

process.

F

inancial planning is a process—the integrated, coordinated, ongoing

management of an individual’s financial concerns. A financial plan is

more than a big document, a stack of investments and insurance policies,

or a file of information about a specific client.

Prior to the advent of financial planning as a profession, most individuals dealt

with a number of specialists who often did not work with each other to

coordinate their efforts on behalf of the common client. Instead, the client had to

try to integrate all the separate areas of his or her financial life. Unfortunately, the

diversity of approaches of the various specialists made it difficult, if not

impossible, for many people to put together a comprehensive financial plan. The

profession of financial planning was created over a quarter of a century ago to

address this problem.

The good financial planner is the quarterback, or coach, of the team of advisers.

Frequently, a financial planner works as a generalist rather than having a specialty

within the financial planning areas of concern. The process of becoming a CFP®

certificant requires mastering the languages of insurance, investments, taxes,

employee benefits, retirement planning, and estate planning. The planner is in the

unique position of understanding all of the experts, coordinating their work, and

translating for the client. In a world of ever-increasing financial complexity, more

and more people seek the assistance of someone who can focus on and keep up with

the changes that affect them. This person is the financial planner.

Chapter 1: The Financial Planning Process

5

© 1981, 1985, 1996, 2002–2015, College for Financial Planning, all rights reserved.

Critical Skills of Planners

Communication. Perhaps the most important skill of a planner is the ability to

communicate complex issues to clients in a way clients understand, empowering

them to act on the information. You may be a great technical planner but you and

the client have wasted time if a client:

doesn’t understand the problem and the consequences of not addressing the

issue

doesn’t go through the process of evaluating your recommendation and the

options

doesn’t make an informed decision and implement a solution

Notice that these are all items the client must be able to complete; it is the

responsibility of the planner to not only tell clients these facts, but make sure

they understand and have the information and skills to complete these items.

Communication skills are a significant factor in how well the financial planning

relationship works. Unfortunately, while many people think of themselves as

good communicators, behavioral economic research shows that we are usually

not as good as we think we are. Consumers report that they frequently find

financial planners difficult to understand and, as a result, a significant number of

planners’ recommendations are not implemented. We strongly urge you to

become a student of communications and behavioral economics so that you can

lead clients through the decision making process.

The following are some basic concepts to apply throughout the planning process.

Engage clients in a discussion about the issue. Since people hear and see

information through their own “lens,” don’t assume that just because you

explained something that your client has the same understanding.

6

Introduction to the Financial Planning Process

© 1982, 1985, 1991, 1996, 2002–2015, College for Financial Planning, all rights reserved.

Explore issues before numerical analysis. Your client won’t solve a problem

he or she doesn’t recognize he or she has. Before you delve into solutions

and strategies, make sure that the client has sufficient time and conversation

so they recognize the issue and want your input in solving it. When the client

can tell you the consequences of not addressing an issue, you know that he or

she understands the problem and has motivation to solve it.

Learn the skills of having tough conversations and be willing to bring up

questions and issues that may cause discomfort and conflict. When we care

deeply about what is being discussed (the issues are important and/or the

outcomes uncertain, which is just about all financial planning situations), we

may perceive the conversation as being difficult.

Listen openly. Listening is of equal or greater importance than talking (and

talking is crucial). Dialogue is a conversation between two or more people;

an exchange of ideas or opinions. At its best, it is not a debate, or an attempt

to convince the other person. Rather, good dialogue provides an opportunity

for joint exploration leading to greater understanding.

Engage clients and encourage them to define characteristics they want in

solutions. This will build ownership and encourage implementation.

Learn to use confirmation skills that include questions such as: “What do you

think the consequence of not acting on this issue would be?” “How do you

think this strategy would benefit you?” “Would the disadvantages of this

strategy impact you?” “What do you think the best solution would be?”

Develop ranges of solutions so that you can always show the client a way

that they can succeed. For example, with a client who has not been saving

you might say, “Our first goal may be replacing 50% of your income at age

70 and when you are saving enough for that, we can drop the target age down

or increase the income.”

Chapter 1: The Financial Planning Process

7

© 1981, 1985, 1996, 2002–2015, College for Financial Planning, all rights reserved.

Remember that as a financial planner, you are a facilitator. It is not up to you

to present the one right answer. In addition to being a financial planning

“expert” resource, your primary contribution may be to help clients explore

options, discuss their feelings about those options, and help them make a

decision with your input (note that the decisions are theirs, not yours, which

is why Step 4 in the financial planning process is worded “Developing and

Presenting Financial Planning Recommendations and/or Alternatives”).

Emotions can play a big part in the conversation and decision-making

process. Studies have shown that many investors’ portfolios underperform

the market as a result of the emotional reactions of investors. For example,

fear of loss can result in making poor choices. The reasons for making a

considerable number of these choices have roots in the individual’s past. The

emotional impact of significant events in a person’s life often contribute to

making inappropriate financial choices today. These “scripts” can impact an

individual’s financial situation in ways that may seem—to the planner—

irrational. Helping the individual gain insight into emotional roadblocks to

better financial health can be one of the most significant activities a planner

can undertake.

Analysis skills. One of the great things about the financial planning profession is

we get to be both analytical and people oriented. Your ability to dissect issues,

create spreadsheets, utilize financial software, understand mathematical formulas

and the implications of them are all part of the planner’s job. Every year new

research is completed providing improved technical knowledge in retirement

planning and investment management. Tax laws change and as a planner, you

will be required to not just learn the new laws but also figure out the

consequences of the changes to your clients and how it may impact the products

and recommendations you are making and have made in the past. One of the

challenges to overcome is building a learning lifestyle into your practice. Many

planners spend hours attending conferences, gaining CE (continuing education)

credits, and even acquiring their master’s in financial planning all in an effort to

keep their analytical skills and technical knowledge current. Common types of

analytical projections and skills you will need to learn include:

8

Introduction to the Financial Planning Process

© 1982, 1985, 1991, 1996, 2002–2015, College for Financial Planning, all rights reserved.

use of financial planning/estate planning/retirement software programs

portfolio analysis and tracking programs

use of Excel spreadsheets to create an analysis of client issues

use of Excel spreadsheets to model results of a specific strategy compared to

an alternative

tax projection programs

detailed comparison of products, features, and benefits and drawbacks in

fields of investments and insurance

Problem solving skills. Financial issues are complex and intertwined in people’s

lives, so it is no surprise that even if we analyze an issue and can clearly see what

the client needs to accomplish, there may be challenges the client will need to

overcome in order to implement the recommendation. Learning to lead clients

through the decision making process and uncovering and resolving barriers along

the journey is important. Again this is an area that would benefit you to develop

these skills. You will utilize these skills and provide assistance for clients

through the financial planning process.

The Steps of the Process

The financial planning process consists of six logical, identifiable steps.

Although these steps are generally taken in order, it is possible that more than

one step might be taken at a single client meeting.

Chapter 1: The Financial Planning Process

9

© 1981, 1985, 1996, 2002–2015, College for Financial Planning, all rights reserved.

Figure 1: The Financial Planning Process

Financial Planning Process Steps

Step 1: Establishing and Defining the

Client- Planner Relationship

Step 2: Gathering Client Data,

Including Goals

Step 3: Analyzing and Evaluating the Client’s

Financial Status

Step 4: Developing and Presenting Financial

Planning Recommendations and/or Alternatives

Step 5: Implementing the Financial Planning

Recommendations

Step 6: Monitoring the Financial Planning

Recommendations

Note: The steps listed above are as identified in the Practice Standards published

by the Certified Financial Planner Board of Standards Inc. (Understanding the

steps and what is done in each is more important than their exact wording.)

It may be helpful for planners and clients to consider the following questions as

they work through the financial planning process.

What is the client’s current condition?

What needs attention; what’s not working right, or for what situations would

they like to prepare?

10

Introduction to the Financial Planning Process

© 1982, 1985, 1991, 1996, 2002–2015, College for Financial Planning, all rights reserved.

What are the consequences of not addressing their concerns or making the

proper preparations?

What are the likely outcomes of any suggested courses of action; how do any

recommendations specifically address their concerns?

Financial Planning Practice Standards

The Certified Financial Planner Board of Standards Inc. (CFP Board) developed

Practice Standards for the ultimate benefit of consumers of financial planning

services. When you gain your CFP mark, you will be agreeing to abide by these

standards. These Practice Standards are intended to:

1. assure that the practice of financial planning by CERTIFIED FINANCIAL

PLANNER™ professionals is based on established norms of practice;

2. advance professionalism in financial planning; and

3. enhance the value of the financial planning process.

The Practice Standards establish the level of professional practice that is

expected of certificants engaged in financial planning.

The Practice Standards state:

The Practice Standards apply to certificants in performing the tasks of

financial planning regardless of the person’s title, job position, type of

employment or method of compensation. Compliance with the Practice

Standards is mandatory for certificants whose services include financial

planning or material elements of the financial planning process, but all

financial planning professionals are encouraged to use the Practice

Standards when performing financial planning tasks or activities addressed

by a Practice Standard.

Chapter 1: The Financial Planning Process

11

© 1981, 1985, 1996, 2002–2015, College for Financial Planning, all rights reserved.

The Practice Standards are designed to provide certificant with a framework

for the professional practice of financial planning. Similar to the Rules of

Conduct, the Practice Standards are not designed to be a basis for legal

liability to any third party.

As you work through the planning process, read the standard that applies to this

process. It will help you better understand what is expected of you as a Certified

Financial Planner professional.

Step 1: Establishing and Defining the Client-Planner

Relationship (Practice Standards 100 Series)

The CFP Board Practice Standards are the definitive set of rules for CFP

practitioners. In each step, we are providing you with the direct language from

the standards. It is this information that you will be tested on and expected to

know well for the comprehensive exam. The standard for step one is listed here:

100-1: Defining the Scope of the Engagement

The financial planning practitioner and the client shall mutually define the

scope of the engagement before any financial planning service is provided.”

Explanation of this Practice Standard

Prior to providing any financial planning service, the financial planning

practitioner and the client shall mutually define the scope of the engagement.

The process of “mutually-defining” is essential in determining what activities

may be necessary to proceed with the engagement.

This process is accomplished in financial planning engagements by:

1. Identifying the service(s) to be provided;

2. Disclosing the practitioner’s material conflict(s) of interest;

3. Disclosing the practitioner’s compensation arrangement(s);

12

Introduction to the Financial Planning Process

© 1982, 1985, 1991, 1996, 2002–2015, College for Financial Planning, all rights reserved.

4. Determining the client’s and the practitioner’s responsibilities;

5. Establishing the duration of the engagement; and

6. Providing any additional information necessary to define or limit the

scope.

The scope of the engagement may include one or more financial planning

subject areas. It is acceptable to mutually define engagements in which the

scope is limited to specific activities. Mutually defining the scope of the

engagement serves to establish realistic expectations for both the client and

the practitioner.

As the relationship proceeds, the scope may change by mutual agreement.

As this explanation from the CFP Practice Standards states, the very first step is

to define and establish the relationship. You will notice that it incorporates

significant disclosures so that the client will have adequate information to retain

your services and prevent misconceptions. During the first meeting with a client,

the financial planner and the client need to mutually define the scope of the

engagement before the financial planning practitioner provides any financial

planning services. Note that this is a mutual process. The client should not dictate

what he or she expects of the planner without the planner agreeing that he or she

is both willing and able to perform the services requested. Also, the planner

should determine if the services requested are warranted and appropriate. This is

true in the reverse as well. The planner should not tell the client what services the

planner thinks the client needs unless the client understands why they are

necessary and agrees they should be provided.

What is involved in “mutually defining”? It includes: (1) identifying the service(s) to

be provided and whether or not the planner is engaged in financial planning; this step

determines the requirements (non-financial planning engagements have slightly

different disclosures and steps than the following); (2) disclosing the financial

planner’s compensation arrangements; (3) determining the responsibilities of the

client and the financial planner; (4) establishing the duration of the engagement; and

Chapter 1: The Financial Planning Process

13

© 1981, 1985, 1996, 2002–2015, College for Financial Planning, all rights reserved.

(5) providing any additional information necessary to define or limit the scope of the

engagement. The scope can include one or more financial planning subject areas

(e.g., estate planning, income tax planning, etc.), and it may change by mutual

understanding as the engagement proceeds.

CFP practitioners are required to deliver in writing a scope of engagement for

each client that incorporates the above components. The CFP Board website has

examples of scopes of engagement and critical disclosures. Creating or learning

your firm’s scope of engagement will be one of your first tasks to accomplish

when you earn your designation. If the planner is a Registered Investment

Adviser and/or a CFP certificant, delivery of additional disclosure documents are

required by law and/or the CFP Board’s Standards of Professional Conduct;

Code of Ethics and Professional Responsibility; Practice Standard 100-1.

Reading the next portion of the module chapter will enable you to:

1–2

Explain the rationale for gathering specific financial information.

This step in the process is the basis for all planning. By necessity, it requires the

most attention.

Step 2: Gathering Client Data Including Goals (Practice

Standards 200 Series)

The CFP Board Practice Standards description reads:

200-1: Determining a Client’s Personal and Financial Goals, Needs and

Priorities

The financial planning practitioner and the client shall mutually define the

client’s personal and financial goals, needs and priorities that are relevant to

the scope of the engagement before any recommendation is made and/or

implemented.

14

Introduction to the Financial Planning Process

© 1982, 1985, 1991, 1996, 2002–2015, College for Financial Planning, all rights reserved.

Explanation of this Practice Standard

Prior to making recommendations to the client, the financial planning

practitioner and the client shall mutually define the client’s personal and

financial goals, needs and priorities. In order to arrive at such a

definition, the practitioner will need to explore the client's values,

attitudes, expectations, and time horizons as they affect the client’s

goals, needs and priorities. The process of “mutually-defining” is

essential in determining what activities may be necessary to proceed

with the client engagement. Personal values and attitudes shape the

client’s goals and objectives and the priority placed on them.

Accordingly, these goals and objectives must be consistent with the

client’s values and attitudes in order for the client to make the

commitment necessary to accomplish them.

Goals and objectives provide focus, purpose, vision and direction for the

financial planning process. It is important to determine clear and

measurable objectives that are relevant to the scope of the engagement.

The role of the practitioner is to facilitate the goal-setting process in

order to clarify, with the client, goals and objectives. When appropriate,

the practitioner shall try to assist clients in recognizing the implications

of unrealistic goals and objectives.

This Practice Standard addresses only the tasks of determining the

client's personal and financial goals, needs and priorities; assessing the

client's values, attitudes and expectations; and determining the client's

time horizons. These areas are subjective and the practitioner’s

interpretation is limited by what the client reveals.

Financial goals are the heart of the financial planning process, because they

define what the client wants to achieve through financial planning. Each

detail of the financial planning process is directed by the financial goals of

the client. The importance of this stage is such that if it is not given the full

attention it requires, the rest of the process has no focus. Frequently

Chapter 1: The Financial Planning Process

15

© 1981, 1985, 1996, 2002–2015, College for Financial Planning, all rights reserved.

exploring and documenting goals will actually be part of establishing the

relationship. Some planners complete some of the soft data gathering

session as part of identifying the scope of engagement. Once the engagement

is determined, the summarized goals and concerns are sent to the client along

with the list of documents needed.

The planner assists the client in establishing realistic goals and quantifying them

in terms of measurable objectives. Goals such as “to be successful” or “to live the

good life” are too nebulous. Financial goals should be quantified in dollar

amounts and have established time frames instead of remaining general in nature.

Quantifying goals makes it easier to estimate savings needed to accomplish the

goal and establish patterns that lead to success. It is important to remember that

the assumptions and goals will shift over time and that our calculations are

estimates. Our process makes it easy for clients to think they will just have “a

plan.” In reality, there will be many iterations of plans over their lifetime.

Planning is a process not a deliverable.

Data Gathering

Data gathering cements the relationship with the client and solidifies the client’s

goals for them. Failure to adequately record all objective and subjective information

may prevent the planner from addressing the client’s motivations, which could result

in the client’s failure to carry out the plan.

The quantity and type of data collected reflects the goals of the client in seeking

financial advice. When a client comes to a financial planner for assistance in

developing a comprehensive financial plan, the data gathered must be extensive.

This is because the planner will assess the client’s risk management program,

investments, tax planning, retirement planning, and estate planning, among other

areas of consideration, and then make recommendations relating to each of these.

On the other hand, the client may come to the planner for specific advice relating

to a smaller area of expertise, such as risk management issues or investment

selection. In these cases, data gathering is limited to issues relating to the specific

16

Introduction to the Financial Planning Process

© 1982, 1985, 1991, 1996, 2002–2015, College for Financial Planning, all rights reserved.

area of concern to the client. It should be noted that the financial planning

process does not change for individuals desiring specific financial help as

opposed to comprehensive help; it still involves setting goals, gathering and

analyzing information, recommending strategies for achieving goals, and

implementing and monitoring plans for changes.

An individual coming to a planner for comprehensive financial planning usually

has some specific reasons for doing so. These reasons normally are transformed

early in the planning relationship into well-defined goals that the client hopes to

achieve through financial planning. The goals may be as varied as the clients

themselves: to do a better job of allocating funds to investments and having them

grow, to plan for retirement or for children’s education, to minimize taxes, or to

simply get one’s financial life under control. Achieving these goals becomes

central to the plan developed by the planner.

However, the planner must also take into account issues that the client may not

have considered on his or her own. For example, an important part of ensuring

the achievement of financial goals is instituting protection against events causing

unanticipated financial difficulty that would hinder long- or short-term goals. If

the client were to experience a period of disability, the financial losses associated

with this could hinder plans for educating children in the near future, unless the

planner anticipates this possibility. In addition, comprehensive planning should

always consider financial needs that exist for all clients, such as retirement and

estate planning.

Planners typically start with identifying the goals clients want to achieve because

they are usually most important to the clients and the motivating factors.

Examples include future major purchases, such as a new home, boat, or car;

travel plans; funding a new business; or providing education for children in

addition to creating a secure retirement Clients also generally want to protect

themselves and their families from adverse occurrences. Clients may not be able to

articulate these goals to ensure adequate protection against personal risks (including

unemployment, disability, death, medical expenses, long-term care issues, property

Chapter 1: The Financial Planning Process

17

© 1981, 1985, 1996, 2002–2015, College for Financial Planning, all rights reserved.

losses, and liability losses). Because clients may have many objectives they would

like to attain, their financial objectives should be ranked in order of importance after

a discussion of the implications of not addressing issues immediately.

For example, retirement may be more important to a client but before

funding retirement is put ahead of funding a term life policy, they must

recognize that the family would be in severe financial straits if a car

accident takes a parent’s life, and then agree to accept that risk before

prioritization. Depending on the nature of the objective, certain constraints, or

limiting factors, need to be considered. Some constraints, such as the availability

of cash flow and existing resources, will be identified to a degree in the data

gathering stage. Later in the financial planning process, the financial planner

needs to consider all factors that might restrict the range of alternatives

appropriate to meeting client needs and achieving client objectives.

The gathering of quantitative and qualitative data is accomplished through a

variety of methods. Refining your process for data gathering is one of the

most critical components to a successful planning practice. Some advisers

have forms they complete; others have forms that they request the client

complete in person or online. Some data gathering forms include everything

needed for specific financial planning software. Other data forms only include

goals and attitudes. The benefit of asking about goals in person is that you

can ask clarifying questions and see the physical reactions to questions.

Forms that clients take home allow them to think more about the answers, but

be careful how much and what information you ask clients to complete. Many

questions that seem simple to you can be confusing to clients, which will

cause them to lose interest in the process.

Many planners have turned interested clients into those who don’t return

phone calls because the clients have not been able to complete the

questionnaire due to lack of understanding, frustration, or not knowing the

answers to their own goals. Some practices involve technical support staff,

such as para-planners, in data gathering to add an additional perspective to

the client’s needs, or simply to facilitate the gathering of facts. It is

18

Introduction to the Financial Planning Process

© 1982, 1985, 1991, 1996, 2002–2015, College for Financial Planning, all rights reserved.

important that the planner gives thought to what he or she hopes to

accomplish for clients, and structure the data gathering process accordingly.

Based on your practice style, you may gather the goals and qualitative

information as part of defining the scope of engagement.

A secondary, but important, benefit of the data gathering session is that it

provides an excellent opportunity to begin educating the client about the

implications of possible problems uncovered during the session. Clients will not

solve problems they don’t believe they have, and hearing about a problem for the

first time along with a solution makes it difficult for clients to choose to solve the

problem. The entire process is facilitated, and implementation much more likely,

if clients have more than one opportunity to explore a problem before making a

decision on fixing it.

You will hear planners talk about gathering qualitative and quantitative data. The

more difficult information to gather comes from the soft questions frequently

referred to as qualitative data. The soft questions are designed to find out what

people want, how they feel, and who they want to benefit. From this dialogue,

you can summarize the client’s goals and concerns that will be addressed during

the planning process. The areas you may explore with clients in a comprehensive

plan would include the following:

Retirement. Generally, this is a high priority goal for most financial planning

clients. You will need both subjective and factual information regarding the

retirement that clients envision for themselves. Until you have done some

quantitative analysis, you may not know whether a client has the resources to

reach their goal, so you may wish to set an ideal goal and a minimum goal so that

you can bring back a plan to the client that will work. Ideal age, income, inflation

assumptions, variations in income, medical expenses during retirement, life

expectancy, and tax assumptions can all be part of this discussion. Capturing the

client’s own words describing their lifestyle goals can be helpful later in the

process. These will be used to establish concrete goals to compare with their

resources to determine what they need to accumulate to achieve their goals.

Chapter 1: The Financial Planning Process

19

© 1981, 1985, 1996, 2002–2015, College for Financial Planning, all rights reserved.

Education or other accumulation goals. Collecting target dates, target amounts

or ranges, expectations about contribution ability, and importance of the goal,

along with contingency plans, will give you the information you need to assess

which strategies can most efficiently help the client achieve his or her goals.

Many clients are not clear on the costs of college or the options for financing college.

You can help lead the discussion by having the costs, potential strategies, and options

at your fingertips during the discussion of goals. Four years of community college

while living at home requires dramatically different plans than six years away from

home at an Ivy League school. Educational expenses have increased substantially in

the past few years and are expected to continue to do so, making it necessary to plan

education funding many years before enrollment. You will also need to determine

whether they have funds earmarked for this goal within their current resources

that may not be clearly marked.

Emergency reserves goal. The process of setting up an emergency fund will help

you and the client understand what could go wrong and how he or she could be

prepared. Engaging the client at this point will ensure that the goal is accepted.

Clearly identifying which funds can be used for emergency reserves versus other

goals will also be important.

Debt management goals and concerns. Direct discussions on use of debt and

strategies for managing and retiring play an important role in freeing up

resources to accomplish goals and have an impact on contingency plans. It also

plays a role in defining an appropriate amount of life and disability insurance,

and establishing emergency fund targets.

Investment management concerns. Uncovering the client’s loss tolerance, risk

tolerance, and sophistication level with investments will allow you to craft a

portfolio that a client will be more likely to adopt and follow during down

markets. Subjective investment data provides information regarding how the

client makes investment decisions, what the client expects from investments,

what the client knows about investing, how the client views risk, and so on. In

addition, the client is asked which of his or her investments have been earmarked

for specific goals, and thus are unavailable for repositioning. Structuring an

investment portfolio is covered in the next CFP course, Investment Planning.

20

Introduction to the Financial Planning Process

© 1982, 1985, 1991, 1996, 2002–2015, College for Financial Planning, all rights reserved.

Health insurance concerns. Exploring this area will allow you to find out about

health problems that may impact the family in an unobtrusive way. Additionally,

knowing whether transitions in coverage may occur or unsatisfactory coverage

exists can impact contingency planning and cash flow.

Disability contingency plan. Planning for disability is frequently overlooked by

clients. The likelihood of disability is greater than the likelihood of premature

death for most wage earners, and it is important that clients be financially

prepared for the impact of disability if other goals are to be met. No one likes to

think that they will become disabled but most recognize the validity of having a

contingency plan. Exploring the consequences of a disability with current

benefits will set the stage for interest in creating a plan that will allow the family

to avoid poverty, and give you the information to complete an analysis and

evaluate options for improving their contingency plan. Gathering information on

group coverage, potential family support, and personal coverage will help you

create the disability protection plan and impact emergency reserves, life

insurance, and cash flow.

Loss of life contingency plan. Having clients explore what would financially

happen upon the death of a spouse and the consequences to children opens their

eyes to the need for appropriate insurance. Taking clients through what

percentage of their current expenses would have to be cut and what they would

cut to reach that amount is enlightening. Defining insurance needs without this

discussion results in off-the-cuff guesses without real thought. After the current

situation is discussed, it is important to define the desired goal including potential

for additional future funding, such as replacing health insurance, weddings, etc.,

in addition to which goals for children and surviving spouse should be funded in

case of death of other spouse. This will impact life insurance analysis, cash flow,

and emergency reserves as new premiums would need to be built into emergency

reserve projection.

Long-term care needs contingency plan. Raising this issue at all ages will bring

out concerns, if they have them, both for themselves and parents in the right age

range. This area frequently needs to be discussed a few years in a row before

Chapter 1: The Financial Planning Process

21

© 1981, 1985, 1996, 2002–2015, College for Financial Planning, all rights reserved.

action is taken. Discussion about expectations of when, why, and how much

long-term care could cost along with how the expenses would be financed, if

needed in the future, will determine whether self-funding or products will

eventually be needed to address this potential issue. Clients in their 50s need to

develop a plan for dealing with these potential expenses as many clients in their

60s will not be able to qualify to purchase long-term care. This not only impacts

long-term care, but cash flow now and in retirement.

Property and liability concerns. It’s important to explore the habits, lifestyle,

volunteer activities, pets, and possessions of a client to uncover risks a client

faces. Any one of the activities listed—sports, hobbies, service on boards of

directors, partnership activities, charity work, etc.—may result in legal liability

and require insurance coverage. This information will be weighed to determine

the benefits and costs of ensuring that the client’s risks are adequately covered.

Learning what clients understand about risk protection will help you formulate an

appropriate plan. A client who has two houses, multiple staff, volunteers on a

board, likes mountain climbing, owns a fishing boat, snowmobiles, and horses

has entirely different risk issues than one who is sedentary, has few possessions,

doesn’t drink, has no children or pets, and drives only five miles to work every

day. Without knowing these facts, your property and liability coverage may not

match the client’s needs. In addition to a liability risk assessment, the needs to

protect property should be uncovered. This will impact cash flow and risk

management analysis.

Legal documents and estate planning distribution plan. Having the right legal

documents in place with the correct representatives is an important part of every

contingency plan. Discussing the wishes of the client regarding provision for

dependents and others after his or her death, who would handle their financial

affairs in case of an incapacity, who will make medical decisions if the client is

incapable, who has rights to access medical information in the family, and what

rights and responsibilities the clients have for other family members are all

important issues. Discussing these issues helps clients get clarity on what they

want, which can then be compared to the documents and state laws that will

determine whether if happens will match what they want to happen. At this time

22

Introduction to the Financial Planning Process

© 1982, 1985, 1991, 1996, 2002–2015, College for Financial Planning, all rights reserved.

it is also important to discuss what inheritances they may have coming or people

that they may need to care for in future years. Gifts that they have made or

received also need to be explored for estate planning purposes.

Anticipated changes in lifestyle, family, health, or other concerns. Opening up

discussion to what else should be talked about will raise any concerns or goals

that the clients have not raised. It also gives the clients a time to provide you

important information that they think you need. Issues such as,” I have cancer,”

“I want to take care of a disabled niece,” “I’ll be inheriting $5 million,” “I’m

getting a divorce,” “My son is a drug addict,” and “I want to be a missionary and

leave my company” are all examples of things that could be raised. If you have

made the client feel comfortable sharing with you, a multitude of issues will be

shared. Health concerns are important to consider in assessing the client’s

potential for achieving future goals, insurance needs and insurability, and special

estate planning needs.

This is also a good time to ask clients to project planned or potential changes in

their income and expenses over the next few years, and identify target cash flow

that you can use to accomplish their goals. Some individuals will have

established a plan of saving and investing or will have made saving and investing

an important use for income. However, many new clients may not have

considered the importance of having a savings target each year as a means of

achieving financial planning goals. These questions help the client focus on the

need to do this. Whether the client succeeds in achieving saving and investing

goals indicates the client’s level of discipline in limiting consumption. It also

may indicate to the planner the amount of effort that will be required to have the

client exercise adequate discipline in adopting and following the developed plan.

This is also a good time to bring up the concept of a budget and find out how the

clients manage their outlays. The process of budgeting and outflows will be

addressed later in this module.

Quantitative data to collect through interview process. Some data you will want

to collect cannot be found on statements but is factual in nature. Family member

names and birthdates help to ascertain when future normal retirement benefits

Chapter 1: The Financial Planning Process

23

© 1981, 1985, 1996, 2002–2015, College for Financial Planning, all rights reserved.

may be available, to plan a schedule for financing the children’s education, and

to determine insurability and life expectancies, among other uses. Names and

contact information for other advisers are needed because as mentioned before,

you may be the quarterback but their specialized skills will be needed. The

current market value of a residence and other personal property is needed for

assessing property and liability coverage, along with implications for debt

restructuring and possible resource in case of death, disability or other risks.

Details on client owned businesses will lead to a discussion of how much and

what business documentation will be needed.

When possible for accuracy, it is best to acquire the statements and policies

rather than interviewing the clients about investments and insurance products that

they own. The benefit is that you will have accurate information and any face-toface time can be spent on understanding their goals and issues. The following is a

list of commonly requested documents required when completing a

comprehensive plan and what you can learn from them. The list will be reduced

if your scope of engagement limits the analysis areas.

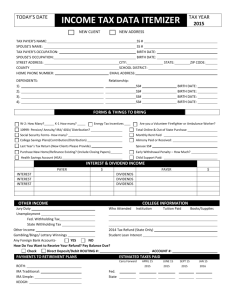

Last two pay stubs. This allows you to see income, employee benefit deductions

indicating which plans they are participating in, tax withholding, and qualified

plan contributions. For example, knowing that a client has not signed up for

group disability would change your analysis and options if you see it is available

in his or her employee benefit package. Widely varying incomes due to

commissions could have impacts for budgeting and emergency reserves. A high

number of exemptions claimed in withholding could indicate taxes may need to

be scrutinized to see if they may owe at the end of the year, and clients may

forget about existing 401(k) loans, which would show as a reduction to income.

Three years’ tax returns including supporting documents such as W2s. These

show you variation in income, interest, dividends and capital gains trends,

dependent status, current itemized deductions, charitable activities, business

relationships, AMT carry-forward, and what is being phased out, which can limit

available strategies. You will be able to identify potential changes that could

improve their tax management and possibly investment returns. This information

24

Introduction to the Financial Planning Process

© 1982, 1985, 1991, 1996, 2002–2015, College for Financial Planning, all rights reserved.

enables the planner to assess the importance of a particular income source and to

plan for its potential replacement in case it is suddenly discontinued (such as

salary during a wage earner’s disability). In addition, it helps the planner assess

the client’s ability to meet financial goals by allocating some of the income to

savings and investments or consumption, as appropriate. By looking at the tax

return and comparing it to investment and bank statements, you can see whether

earnings are being reinvested or being spent to support lifestyle. Contributions to

IRAs, education savings programs, etc. can be confirmed. Rental property, royalties,

or other forms of income that may not have formal statements will be uncovered.

Cash flow statements. For clients who use programs such as Quicken or Mint,

bringing cash flow statements can be very helpful and save the adviser time.

Constructing outflow statements can be time consuming, and clients frequently

do not know where their money goes. Many advisers will introduce clients to

programs such as Mint.com, which can capture the last three to six months’

spending and categorize them quickly. You can back into spending by using the

taxable income and subtracting taxes and savings, adding increases in credit or

spending of assets to arrive at what was spent during the year. This will give you

an estimate of lifestyle costs but no ability to find potential savings.

If you do get cash flow statements, you can learn what their intentional savings

plans are versus actual behaviors, debt repayment plans to calculate debt ratios,

and potential opportunities for restructuring cash flow to free up funds to

accomplish goals. This can help you determine whether more focus needs to be

on cash flow management or investment management. You can learn how well a

client manages his or her money and whether debt is an issue to be addressed.

Benefit package descriptions. Policies that explain the group life insurance

amounts for completing life insurance analysis; medical, dental and vision

coverage to help you understand potential out of pocket costs; flexible

spending plan opportunities for potential tax savings; sick days, short-term

and long-term disability benefits for disability analysis; long-term care

options offered by employers; 401(k), pension, and other retirement

Chapter 1: The Financial Planning Process

25

© 1981, 1985, 1996, 2002–2015, College for Financial Planning, all rights reserved.

opportunities and rules for your retirement, life, and disability analysis.

Knowing why they selected the benefits they did and did not select will help

you understand the client’s reasoning process. Both of these may impact your

contingency planning.

Copies of personal insurance policies and latest statements. The face pages on

personally owned medical, automobile, homeowners, umbrella, life, disability,

long-term care policies, professional and business policies, etc. will let you know

exactly the type, constraints, owners, coverage, and premiums to ensure accurate

analysis. You will need to explore the value of property and assess potential risks

through the interview process in order to evaluate the adequacy of their risk

program. In addition to evaluating the adequacy of coverage, the type of policy

and riders will be important. For example, the client may have the right amount

of life insurance but it may be a term policy which will terminate before the need

ends. Knowing whether health insurance is provided through employers,

Medicare with or without supplements, or through the exchanges can let you

know the time frame for making potential changes. You cannot complete a risk

assessment without this information.

Investment and bank statements including retirement accounts. Gathering year

end and current statements will let you see ownership, value, basis, and dates of

acquisitions, which all have potential tax implications. Based on the size of the

client’s estate, you may need to gather further information for estate tax analysis

such as state of domicile at time of acquisition (community property laws follow

the asset even when the client moves). Having the exact names and shares will

give you the information to complete an accurate asset allocation. This will also

let you determine the appropriate returns to use in projecting retirement,

education, and goal calculations.

Knowing exact ownership is important because some methods of titling assets

involve automatic transfer of a deceased owner’s interest to another owner, thus

avoiding the probate estate, while other methods involve the distribution of property

through the probate process, requiring adequate provisions in the will. The titling of

assets may also be important in the lifetime distribution of property or division of

26

Introduction to the Financial Planning Process

© 1982, 1985, 1991, 1996, 2002–2015, College for Financial Planning, all rights reserved.