U.S. Public Libraries and the Use of Web Technologies, 2010

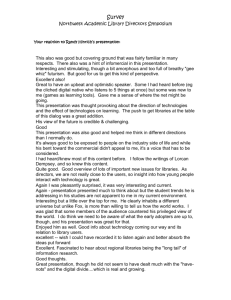

advertisement