ISM UNIVERSITY OF MANAGEMENT AND ECONOMICS MASTER

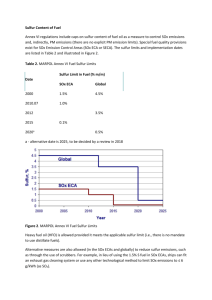

advertisement