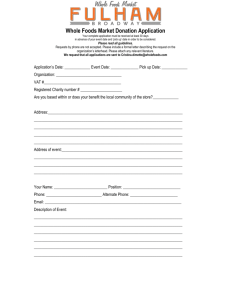

14b. Whole Foods Human Resources - e

advertisement