Accounting for Manufacturing and Inventory Impairments

advertisement

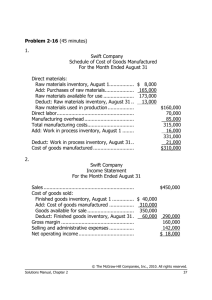

Accounting for Manufacturing 1 Accounting for Manufacturing and Inventory Impairments TABLE OF CONTENTS Accounting for manufacturing 2 Production activities 2 Production cost flows 3 Accounting for production activities 4 Acquiring production resources 4 Using resources during production 5 Completing production 10 Accounting for cost of sales 11 Accounting for inventory impairments 14 © 1991–2013 NavAcc LLC, G. Peter & Carolyn R. Wilson 2 Navigating Accounting ® ACCOUNTING FOR MANUFACTURING This section extends our study of accounting to manufacturing companies. In contrast to retailers like The Gap and Home Depot, that largely purchase the goods they sell to customers, manufacturers like General Electric and Intel produce most of the goods they sell. We will use the terms “production” and “non-production” to describe various business activities. Production activities are those associated with producing or manufacturing products. Nonproduction are all other activities of the business. For example, a company may purchase a computer that will be used in manufacturing products: production equipment. The same company may purchase another computer that will be used in the marketing department: non-production equipment. This distinction is important for accounting purposes, as you will see. The section is organized as follows: • Production activities • Production cost flows • Accounting for production activities • Acquiring production resources • Using resources during production • Completing production • Cost of sales Production activities The key difference between manufacturers’ and retailers’ operations is manufacturers produce the goods they sell: © 1991–2013 NavAcc LLC, G. Peter & Carolyn R. Wilson Accounting for Manufacturing 3 For reasons that will become apparent when we start recording entries, resources acquired for production are classified into three groups: (1) Resources held in inventory until they are needed in production, such as materials and supplies (2) Resources gradually used up (depreciated or amortized) over time during production, such as PP&E and patents. (3) Resources acquired as they are used in production, such as labor and parts from suppliers arriving “just-in-time” for production. Production cost flows Production accounting provides considerable information associated with these business activities for internal decisions such as assessing whether production costs and processes are under control, determining and controlling inventory levels, and pricing products. Accountants also determine cost of sales for financial reporting. To this end, they need to determine the cost of each product sold through a process called product costing. At the big picture level, this © 1991–2013 NavAcc LLC, G. Peter & Carolyn R. Wilson 4 Navigating Accounting ® involves recording costs as they are incurred; flowing these costs through accounts associated with the above activities; and assigning them to specific products. The details associated with assigning costs to specific products are far beyond the scope of this chapter. Here, we will abstract from these details by describing how the aggregate costs (for all products produced) flow through three types of inventory accounts associated with these activities: materials inventory, work-in-process inventory (WIP), and finished goods inventories (FGI). The figure below illustrates how these inventory types relate to production activities and the four-step process accountants use to track resource costs through these activities: (1) Record the costs of production resources as they are acquired. (2) Assign the costs of production resources to work-in-process (WIP) as resources are used. (3) Transfer costs from WIP to finished goods inventory (FGI) when production is completed. (4) Transfer costs from FGI to cost of sales when goods are delivered to customers or to deferred cost of sales or consignment inventories when revenue recognition is deferred at delivery. Accounting for production activities Next we will discuss in broad terms the accounting issues that arise at each of these steps and record entries that capture the general flow of production costs. In doing so, we will abstract considerably from the detailed entries that are typically recorded, an understanding of which is not needed to interpret financial statements. Acquiring production resources Most of the entries that record the costs of acquired production resources are similar to entries studied earlier. For example, recording the purchase of raw materials is similar to recording the purchase of merchandise for resale except the name of the inventory account differs slightly (e.g., raw © 1991–2013 NavAcc LLC, G. Peter & Carolyn R. Wilson Accounting for Manufacturing 5 materials inventory instead of merchandise inventory). Similarly, recording the purchase of PP&E is the same for production and non-production PP&E. By contrast, recording the costs of resources does differ from earlier entries, such as labor and electricity that are incurred as these resources are used in production. These costs are assigned to work-in-process when they are incurred. It will be much easier to explain the related record keeping after we describe these events in more detail in the next section. Examples Smart Company acquires two resources during fiscal 2013 prior to using them in production: purchased $100 of parts and materials inventories on account and $1,000 of production-related PP&E for cash. Here are the related entries: Smart Company: Resources acquired prior to production Purchase parts and materials on account Parts and materials inventories Accounts payable Purchase production-related PP&E with cash PP&E (historical cost) Cash and cash equivalents Debit Credit $100 $100 Debit Credit $1,000 $1,000 These entries are similar to those that would be recorded by a retailer, except the parts and materials account would be called finished goods inventories or simply inventories. The entry to record the purchase of production-related PP&E is identical to the entry to record non-production-related PP&E, such as the corporate headquarters. However, as we shall see, the entries to record related depreciation differ significantly. Using resources during production As resources are used during production, their costs are assigned to work-in-process. As indicated at the top of the next page, first costs are classified as direct or indirect. Direct costs can be connected very precisely to specific products. For example, they include compensation costs for employees who work exclusively on one product or on a group of similar products and the costs of parts and materials that can be traced to specific products. By contrast, indirect costs can’t be traced precisely to products. For example, they include utilities and supervisor costs that can’t be traced precisely to products. While indirect costs can’t be associated precisely with products, they can often be associated imprecisely to products through a product costing process. © 1991–2013 NavAcc LLC, G. Peter & Carolyn R. Wilson 6 Navigating Accounting ® Recording direct costs to WIP Direct costs are transferred to WIP when resources that were previously acquired are used in production. Additionally, direct costs associated with resources that were not stored prior to production, such as direct labor, are recorded to WIP accounts as these costs are incurred. Large manufacturing companies that produce thousands of products have numerous WIP accounts. Information from these accounts is used for internal decisions such as inventory control and product pricing. For financial accounting, these accounts are combined into a single WIP account that is disclosed on the balance sheet or in footnotes. As indicated earlier, here we will use a single WIP account that aggregates the activity in the separate product accounts. © 1991–2013 NavAcc LLC, G. Peter & Carolyn R. Wilson Accounting for Manufacturing 7 Examples Smart Company has two costs that can be traced directly to the production of specific products: parts and materials inventories used during production and labor costs for employees whose work on assembly lines can be traced directly to products. During fiscal 2013, Smart used $80 of previously purchased parts and materials in production and accrued $90 of direct labor costs. Here are the related entries: Smart Company: Recognizing direct production costs Using parts and materials inventories Work-in-process Debit Parts and materials inventories Accruing direct labor costs Work-in-process Credit $80 $80 Debit Credit $90 Accrued liabilities $90 One of the keys to learning production-related entries is to recognize how they compare to nonproduction-related entries you already know how to record. To this end, we are going to compare the above entry to accrue $90 of direct labor costs to the entry Smart records during fiscal 2013 to accrue $105 of non-production-related compensation costs. (For example, employees working in the factory versus those working at the corporate office.) Smart Company: Contrasting production-related and non-production-related entries to accrue compensation Accruing direct labor costs to production Work-in-process Debit Accrued liabilities Accruing non-production-related compensation Selling, general and administrative expenses Accrued liabilities Credit $90 $90 Debit Credit $105 $105 Both entries recognize Smart’s obligation to pay employees for services rendered, but their financial statement consequences differ significantly. In particular, accruing non-production-related compensation results in an expense, while recognizing production-related compensation results in an asset being recognized. © 1991–2013 NavAcc LLC, G. Peter & Carolyn R. Wilson 8 Navigating Accounting ® The difference in these entries can easily be understood using the four questions and OEC Map approach we have been using throughout the course to record entries. We will first demonstrate this approach for accrued compensation associated with non-production-related employees. Recall our earlier responses to the four questions when we accrued compensation: 1. Should an asset be recognized? Generally, we would expect future benefits to be created when non-production-related employees work. For example, we would expect future benefits to be realized when employees at the corporate headquarters are working on marketing strategies. However, these benefits can’t be measured reliably and, in particular, determining when, if ever, the benefits are realized is problematic. Thus, the answer to this question is no: an asset is not recognized when non-production-related compensation is accrued. 2. Should an asset be de-recognized? No. There is not a related previously recognized asset to de-recognize. 3. Should a liability be recognized? Yes, the company is obligated to pay the compensation. 4. Should a liability be de-recognized? No. There is not a related previously recognized liability to de-recognize The third question is the only one we answered affirmatively, which means net assets and thus owners’ equity decreases when compensation is accrued for a non-production-related employee. From the OEC Map, we can easily determine that an expense is recognized. What is different with production-related depreciation? The answers to all of the questions above except the first will be the same. Should we recognize an asset when production-related compensation is accrued? Yes: An asset should be recognized. The direct labor employed during production helped produce inventory, whose future benefits will be realized when products are sold. So the distinguishing difference is we can now determine when the future benefits have been realized: when the product is sold. This was not true for non-production-related compensation. More generally, as we shall see, the cost of all resources used to produce products are recorded to inventory. By contrast, costs associated with using similar resources in non-production activities are expensed as the resources are used. Recording indirect costs to WIP Indirect costs, which can’t be precisely associated with specific products, are assigned to overhead accounts called “ overhead pools”, which are groups of costs that tend to be correlated with one or more factors that are associated with production. For example, in many production contexts the cost of utilities and the cost of using equipment (depreciation) are highly correlated with the number of hours that the equipment is operated (machine hours). When such correlation occurs, it is common to group utilities costs, depreciation, and other costs that are correlated with machine hours into a single overhead pool. Similarly, in some contexts, overhead cost pools are created when groups of costs are highly correlated with direct labor or materials usage. © 1991–2013 NavAcc LLC, G. Peter & Carolyn R. Wilson Accounting for Manufacturing 9 The costs in these overhead pools are subsequently aggregated and assigned to products’ individual WIP accounts using product costing formulas that are beyond the scope of this chapter. As indicated earlier, we are focusing on aggregate cost flows rather than flows into specific products. Accordingly, rather than recording incurred costs first to overhead pools and then to WIP, we will simply record them directly to WIP: Examples Recall from earlier chapters that expenses associated with using non-production-related resources can be recognized before, at the same time, or after the cash outflows to acquire these resources. For example, expenses can be prepaid or accrued. Likewise, the costs associated with using productionrelated resources can be recognized in WIP before, at the same time, or after the cash outflows to acquire these resources. © 1991–2013 NavAcc LLC, G. Peter & Carolyn R. Wilson 10 Navigating Accounting ® Next, we will provide several examples to illustrate that the only difference between the entries to use non-production-related resources and production-related resources is that expenses are debited in one case and WIP in the other. For each example, the reason for recognizing an asset in one case and an expense in the other is the same as for the earlier accrued compensation example: we know when the future benefits associated with WIP will be realized (when products are sold). In our first example, we compare the entries Smart recorded during fiscal 2013 for using previously prepaid rental property for production-related versus non-production-related activities. Smart Company: Contrasting production-related and non-production-related entries to use prepaid rental property Using rental property for production-related activities Debit Work-in-process $75 Prepaid rent Using rental property for non-production-related activities Credit $75 Debit Selling, general and administrative expenses Credit $85 Prepaid rent $85 In our second example, we compare the entries Smart recorded during fiscal 2013 for using PP&E for production-related versus non-production-related activities. Smart Company: Contrasting production-related and non-production-related entries to use PP&E Using rental property for production-related activities Work-in-process Debit $120 Accumulated depreciation Using rental property for non-production-related activities Depreciation expense Accumulated depreciation Credit $120 Debit Credit $70 $70 Completing production When production is completed, products are generally transferred to warehouses where they are stored until they are sold and delivered to customers. At this time, their costs are transferred to finished goods inventories. The amount transferred is determined by multiplying the cost per unit © 1991–2013 NavAcc LLC, G. Peter & Carolyn R. Wilson Accounting for Manufacturing 11 times the number of units completed. Similar to work-in-process, typically products or similar groups of products have separate finished goods inventories accounts that are used for internal decisions and aggregated for financial reporting. Example During fiscal 2013, Smart Company completed production on products with $350 of inventoried costs, meaning costs previously charged to inventory. Here is the entry: Smart Company: Transferring completed products to FGI Debit Finished goods inventories Work-in-process Credit $350 $350 Accounting for cost of sales When products are sold and delivered to customers, costs are transferred out of finished goods inventory. As we shall see in this section, where they are transferred to depends on whether revenue is recognized at the time of delivery. © 1991–2013 NavAcc LLC, G. Peter & Carolyn R. Wilson 12 Navigating Accounting ® Companies recognize revenue and cost of sales when they have met the recognition criteria. Generally, the criteria are met when products are delivered, at which time companies decrease FGI and increase cost of sales. However, GAAP requires companies to defer revenue and expense recognition if the criteria have not been met. GAAP requires the related costs to stay on the seller’s balance sheet until revenue is subsequently recognized. That is, cost of sales is deferred when revenues are deferred. However, GAAP doesn’t specify how the deferred costs should be presented on the balance sheet and our research suggests at least two approaches are practiced: • Leave the deferred costs in inventory, possibly segregated from other finished goods inventory either disclosed on the balance sheet or in a footnote. For example, Cisco segregates “Distributor inventory and deferred cost of sales” from “Manufactured finished goods” in the Inventories section of its Balance Sheet Details footnote: July 28, 2012 July 30, 2011 $127 $219 35 52 Distributor inventory and deferred cost of sales 630 631 Manufactured finished goods 597 331 Total finished goods $1,227 $962 Service-related spares 213 182 Demonstration systems 61 71 $1,663 $1,486 Inventories: Raw materials Work-in-process Finished goods Total Cisco's 2012 10-K, page 98, Inventories section of Note 6 (Balance Sheet Details), sec.gov The SEC recommended this approach when companies were forced to restate their financial statements after the SEC brought enforcement actions against them for improperly recognizing revenue. The SEC concluded the sales that were previously recognized as revenue should have been treated like consignment sales. For consignment sales, the seller delivers the product, but retains substantially all of the risk of ownership, the inventory remains on the seller’s books and the inventory is reclassified as consignment inventory. Under consignment sales agreements, retailers/buyers do not assume ownership of delivered products (title does not transfer) and are not obligated to pay for them until they resell them to their customers. Inventories associated with deemed consignment sales can be included with finished goods inventories (as Cisco does) or segregated from them. • Report a deferred income liability: deferred revenues less deferred cost of sales. While Intel doesn’t explicitly state that it nets deferred cost of sales against deferred revenues, it has reported a deferred income liability rather than a deferred revenue liability for several years. In fact, Intel followed this practice before the SEC started characterizing sales similar to the ones where Intel defers revenues as consignment sales. © 1991–2013 NavAcc LLC, G. Peter & Carolyn R. Wilson Accounting for Manufacturing 13 Examples Smart Company defers $130 of revenue on a cash sale of a product with $80 of inventoried costs. Here are the entries Smart would recognize if it treats the sale as a consignment sale and transfers the costs to a segregated inventory account that is not included in finished goods inventories. Smart Company: Revenue is deferred and sale is treated as a consignment sale with inventory segregated from FGI Defer revenue on cash sale Debit Cash and cash equivalents Deferred revenue Credit $130 $130 Defer cost of sales and segregate inventory from FGI Segregated inventories: deferred revenue Finished goods inventories Debit Credit $80 $80 Here are the entries Smart would record if it reports a deferred income liability on its balance sheet and maintains a separate deferred cost of sales contra liability to its deferred revenue liability: Smart Company: Revenue is deferred and a deferred income liability is recognized: deferred revenues less deferred costs Defer revenue on cash sale Debit Cash and cash equivalents Deferred revenue Credit $130 $130 Defer cost of sales and segregate inventory from FGI Deferred cost of sales (contra liability to deferred revenues) Finished goods inventories Debit Credit $80 $80 © 1991–2013 NavAcc LLC, G. Peter & Carolyn R. Wilson 14 Navigating Accounting ® ACCOUNTING FOR INVENTORY IMPAIRMENTS Under both IFRS and US GAAP, inventory must be impaired (written down) when management anticipates a future sale will result in a loss. However, the formulas for determining the impairments differ and impairments can be reversed under IFRS, but not under US GAAP. We will use an example to illustrate these differences and introduce related concepts. Example Facts ■ On October 30, 2013 a sudden drop in demand leads Smart Company to drop the sales price of one of is products from $20 to $9 per unit. ■ The carrying value of each unit in inventory on that date, which is also the historical cost, is $10. ■ Smart expects it will incur $2 of additional costs to sell each unit. This means the net realizable value of future sales is expected to be $7: the $9 sales price less the $2 of additional costs. ■ Smart has 100 units in inventory on October 30, 2013. ■ Smart estimates the replacement cost of the inventory on October 30, 2013 is the same as its historical cost, $10 per unit. ■ Smart writes down the inventory on October 30, 2013 (as indicated below). ■ On November 1, 2013 Smart sells one unit for $9 cash. Prior to the write down On October 31, Smart expects to realize a loss of $3 on future sales of each unit in inventory: -$3 = $9 sales price less $2 of additional cost less $10 of inventoried costs. Thus, it expects to realize a total loss of $300 on the 100 units in inventory. More generally, the gain or loss that is expected to be realized when inventory is sold is its expected net realizable value less its historical cost. Given the example’s facts and, in particular, the replacement cost assumption, the same impairment must be recognized on October 31st under US GAAP and IFRS: $300. We will outline how the impairments can differ under IFRS and US GAAP later and direct you to a “Drill Deeper”video that has a detailed explanation of these differences. Because impairments can be reversed under IFRS, they must be recorded to an allowance for accumulated impairments that is a contra asset to finished goods inventories (so companies can keep tract of the amount that can be reversed in the future). By contrast, because reversals are not permitted under US GAAP, companies can maintain allowances or write-off finished goods directly. As we shall see, the two approaches have the same financial-statement effects. Here are the entries to record the $300 October 31st impairment and sale of one unit for $9 on November 1st (with and without an allowance): © 1991–2013 NavAcc LLC, G. Peter & Carolyn R. Wilson Accounting for Manufacturing 15 Smart Company's inventory impairment entries, using an allowance October 31: Inventory write down in anticipation of a loss Cost of goods sold Allowance for inventories impairments Debit Credit $300 $300 November 1: Previously written down inventory is sold Recognize revenue Cash and cash equivalents Revenues, net Debit Credit $9 $9 Recognize cost of sales Allowance for inventories impairments Cost of goods sold Finished goods inventories $3 $7 $10 Smart Company's inventory impairment entries, without an allowance October 31: Inventory write down in anticipation of a loss Cost of goods sold Finished goods inventories Recognize cost of sales Cost of goods sold Finished goods inventories Credit $300 $300 November 1: Previously written down inventory is sold Recognize revenue Cash and cash equivalents Revenues, net Debit Debit Credit $9 $9 $7 $7 As indicated earlier, the approaches used to determine impairments differ under IFRS and US GAAP will generally result in different impairment amounts. The IFRS approach is relatively straightforward: the carrying value of inventory at each balance sheet date must be the lower of cost or net realizable value. This means whenever the net realizable value is lower than the cost, the accumulated impairment allowance must ensure the carrying value is the net realizable value. That is, the allowance balance must ensure the following: net realizable value = cost allowance. No allowance is recognized when the cost is lower than the net realizable value. An adjusting entry at each balance sheet date ensures the allowance has the correct balance. When this entry increases the allowance, cost of sales increases (as it did above in the example). When the adjusting entry decreases the allowance, there is a reversal, and cost of sales decreases. (The reversal can’t exceed the allowance balance prior to the reversal.) © 1991–2013 NavAcc LLC, G. Peter & Carolyn R. Wilson 16 Navigating Accounting ® The IFRS test for impairment compares cost to expected future selling prices adjusted to net realizable value. Thus, it is based on costs and price changes in a single market: the product or output market. For example, Smart Company recognized an impairment when there was a significant decrease in the expected future selling price of the inventory. Importantly, IFRS impairments are not affected by replacement costs. That is, by changing prices in the input market where it purchases inventory or resources to produce inventory. By contrast, impairments under US GAAP can be affected by price changes in either the input or output market. For example, suppose the expected future selling price of Smart’s inventory had NOT decreased from $20 to $9 on October 31, 2013, but the replacement cost dropped to $8 (because of supply side cost savings). Under US GAAP, Smart would recognize a $2 impairment to ensure the carrying value of its inventory did not exceed its replacement cost. On the surface, similar to IFRS, the carrying value requirement for inventories under US GAAP seems to be relatively straightforward: the carrying value is the lower of cost or market. In fact, determining impairments is straightforward once you know “market.” However, as suggested above, “market” is derived using information from two markets (input and output). The related formula is rather clever once you figure it out, but beyond the scope of this chapter. Drill deeper - beyond the scope of this chapter. For a detailed explanation of the lower of cost or market rule, view the “US GAAP” menu items of the Navigating Accounting “Inventory Impairments” video: http://www.navigatingaccounting.com/video/scenic-inventory-impairments © 1991–2013 NavAcc LLC, G. Peter & Carolyn R. Wilson