Contextual Framework of the Chain of Firm-Acquisitions

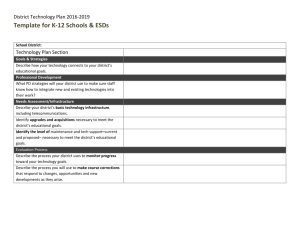

advertisement