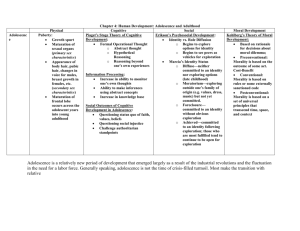

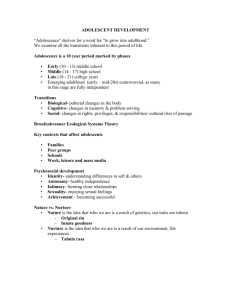

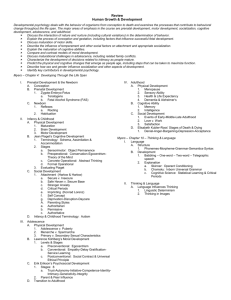

Adolescence and Adulthood

advertisement