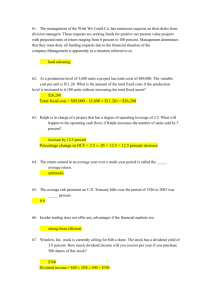

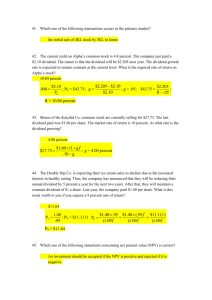

CORPORATION TAX AND INDIVIDUAL INCOME TAX in the

advertisement