Tax Haven

advertisement

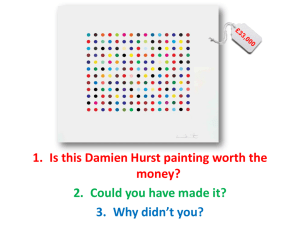

Taxation and Illicit Financial Flow Yustinus Prastowo Center for Indonesia Taxation Analysis Subject to be discussed: • • • • International inequality/tax evasion. Tax Haven, Secrecy Jurisdiction. BEPS. Tax Planning, Tax Avoidance, Tax Evasion. “ For each dollar of aid that goes into Africa, at least five dollars flows out under the table. The time has come to confront the tax haven monster. ” fair and transparent payment of tax is at the heart of the social contract between business and society Marc Lopatin No. 243, May 2004 30th May 2007 3 • Global Financial Integrity (GFI) estimates that illicit financial outflows from the developing world totaled a staggering US$946.7 billion in 2011, with cumulative illicit financial outflows over the decade between 2002 and 2011 of US$5.9 trillion • Indonesia is a country with USD 18 mio/year IFF. 4 Some statistics In 1996 money laundering was estimated to be between USD 590Bn to 1,5 Trillion World Bank estimates the value of criminal activities, corruption and tax evasion to be between $1 trillion and $1.6 trillion per year OECD estimates that 50% of all cross border trade is made via tax havens In 2004 US MNE’s paid 2,3 % in tax (16 bn on 700 bn of foreign active earnings) In 2006 UK established that 3,5 % of tax payers provide information re offshore accounts. 5 “One recent worldwide estimate of individual income evasion losses attributable to the tax havens, based on a straightforward methodology, was $ 255 billion. Based on the ratio of estimated offshore wealth to the total, the U.S. and Canada would be losing over 45 billion, Europe about 74 billion, the Middle East and Asia about 116 billion and Latin America nearly 20 billion….National stakes in such losses propelled the EU, Japan, and the United States to launch a coordinated attack in 1998.” --- Robert T.Kudrle COMPARISON INDONESIA TAX RATIO TO OTHER COUNTRIES Keterangan: *Hasil kalkulasi Prakarsa dengan Pendekatan Tax Ratio dalam arti luas Sumber: IMF 2011 (diolah) The main problem/challenges: • • • • • • Existence of tax haven/secrecy jurisdiction Transfer Pricing practice Abuse of tax treaty International tax structuring Lack of exchange of information The “myth’ of international tax law Some statistics (cont.) BVI has 19,000 inhabitants but 830 000 companies registered One address alone in the Cayman Islands serves as the registered office for > 18 000 companies Assets equal 1,3 times GDP in Norwegian banks, 2,5 times GDP for the Euro zone. In Cayman Islands the assets total > 700 times the GDP 9 Convenient knowledge: CFC – Controlled Foreign Corporation DTT – Double Tax Treaty FBAR – Foreign Bank Account Report (US) LOB – Limitation of Benefits QI – Qualified Intermediary Tax Haven - ? TIEA – Tax Information Exchange Agreements White, Grey, Black List – CFC-related lists 10 Overview Tax Haven A country or territory that has lower or no taxes and provides a safe place for deposits in order to attract capital Tax havens create tax competition among governments in order to maintain or attract depositors via the altering of banking/fiscal policies and rules. 11 12 Tax haven Debate For • Avoidance of excessive tax burden • Greater security and lower risk • Privacy • Tax competition encourages pro-growth tax policies 13 Tax haven Debate Against • Lack of transparency • Tax avoidance and loss of tax revenue • In some instances, it perpetuates illegal activity i.e. money laundering 14 Tax Havens - The top five secrecy jurisdictions Delaware, US: The world's top secrecy jurisdiction. Register a company here and no one will ever know. If you have overseas income, it will be tax exempt. Luxembourg: Europe's most powerful investment management centre. It does require company accounts to be publicly available. But in virtually every other category secrecy rules. Switzerland: The traditional home of the opaque bank. For years, it resisted international requests for tax information exchange. Cayman Islands: The Caribbean island has a serious budget crisis. Its leaders take a dim view of having the "good name" of the most powerful hedge fund centre tarnished by accusations. City of London, UK: The International Narcotics Control Strategy Report said last year: "Illicit cash is consolidated in the UK and then moved overseas where it can readily enter the legitimate financial system." It adds: "Drug traffickers and other criminals are able to launder substantial amounts of money in the UK despite improved anti-money laundering measures.“ guardian.co.uk 15 Integrated financial markets pose new global challenges • New opportunities for illicit activities: – Money laundering – Misuse of corporate vehicles – Terrorist financing – Tax abuse – Threats to stability of financial system All activities which thrive in climate of secrecy, non-transparency and non-cooperation 16 The response of governments • Launching the FATF (Financial Action Task Force) • Creating the FSF (Financial Services Forum) • Creating the OECD Forum on Harmful Tax Practices • Parallel tracks but common goals: – To improve transparency – To raise governance standards in financial centers – To encourage cooperation to counter abuse 17 Offshore is a big and growing issue $5-7 trillion held offshore 300,000 Shell Companies in the BVI $9.4 billion from BVI to China Brazil reports a deficit of $4 billion trade with Caribbean Islands • Singapore now 3rd biggest private wealth centre after Luxemburg and Switzerland • Caymans 5th largest deposit banking center in the world (population 46,600) • • • • 18 International Offshore Financial Centers 17 What does OECD mean by a tax haven? • Jurisdictions characterized by: – Lack of transparency – Lack of effective exchange of information • So a low tax jurisdiction is not necessarily a tax haven 20 Much money held offshore is there legally OFCs may: – Offer legitimate tax planning opportunities – Provide a neutral regulatory environment for residents of other countries to do business e.g. collective investment funds; captive insurance – Be used for non-commercial reasons 21 Yet revenue implications of the illegitimate use of tax havens can be serious • Ireland collects almost €900 million from Irish residents with offshore Channel Island accounts • Italian tax amnesty results in €84 billion being repatriated, of which one-third from Switzerland • Senate Finance Committee quotes estimates of $4070 billion lost to tax havens • UK expects to recover £1.9 billion from its recent clampdown on offshore evasion The reality is we don’t know exactly, but sums are large. 22 The broader policy implications Reducing effective tax rates by encouraging tax evasion is not good tax policy – MNEs and individuals can use tax havens to reduce tax rates – This is not good tax policy since: • It undermines the fairness and the integrity of the tax system • It either: Restricts the ability of government to reduce tax rates for all Requires government to increase tax rates on labor or consumption with negative impact on labour markets Or forces expenditure cuts Or raises deficit • As a matter of public policy, condoning tax abuse is bad politics 23 OECD objectives • What does the OECD seek? – improved transparency – improved exchange of information – a co-operative approach • What is not sought? – harmonization or setting minimum tax rates – impinging on national fiscal sovereignty – an unfair competitive advantage for OECD financial centers • Two linked initiatives: – 1998 initiative on Harmful Tax Practices – 2000 on improving access to bank information 24 OECD approach Recognizes: – Interest of government in protecting integrity of tax system and confidentiality of taxpayer information – Interest of business community in avoiding excessive burden – Countries’ right to tailor their own tax systems to their own needs – The need to move towards a level playing field and mutual benefits 25 Transparency • Standard developed with co-operative offshore financial centers • Key elements – reliable books and records – beneficial ownership information – access to bank information • Transparency unlikely to be a significant concern for bona fide business 26 Key principles in model agreement on exchange of information • On request only • Covers civil and criminal tax matters • Requests cannot be rejected on grounds of dual criminality requirement or absence of domestic tax interest • Parties must have power to obtain bank and ownership information • Information must be ‘foreseeably relevant’ • No fishing expeditions • Protection of taxpayer confidentiality Almost no compliance burden on business 27 State of play : tax haven work Only 5 offshore jurisdictions now listed as un-cooperative tax havens: Andorra Monaco Liechtenstein Marshall Islands Liberia 28 State of play: offshore financial centers 33 offshore jurisdictions committed to transparency and effective exchange of information: Aruba Antigua Anguilla Bahamas Bahrain Belize Bermuda British V.I. Cayman Is. Cooks Is. Cyprus Dominica Guernsey Grenada Gibraltar Isle of Man Jersey Malta Mauritius Montserrat Neth. Antilles Niue Nauru Panama Samoa San Marino Seychelles St. Kitts & Nevis St. Vincent St. Lucia Turks & Caicos US Virgin Is. Vanuatu 29 STRUCTURE/SCHEME 30 Example 1 Use of (high tax) jurisdictions to establish conduit entities: Loan Loan NL INVESTORS Interest ITALY Interest 31 Discussion Transfer pricing Treaty application Limitation on Benefits ? Concept of Beneficial Ownership 32 Example 2 Use of “Hybrid” corporate structures to optimise taxation of interest Equity Loan 33 Discussion Qualification legal entities in multiple jurisdictions 34 Example 3 Use of Special Tax regimes TOP CO FIN CO OP CO OP CO Loan 35 Myth and Reality 36 There aren’t any tax havens any more The myth: • “The era of bank secrecy is over” (G20, 2009) The reality: • The OECD set the bar extremely low – at 12 tax information exchange agreements (TIEAs) that can be signed with each other • When blacklist was introduced, only 4 countries were on it. • Essentially overnight they signed the requisite TIEAs and were removed from the blacklist • TIEAs require you to know the answer before you can ask the question 37 There aren’t any tax havens any more The reality: • For example only 4 pieces of information were exchanged between the USA and Jersey in 2008 • Christian Chavagneux of the OECD said “France made 230 requests for information to 18 countries in the first eight months of 2011. The reply rate was only 30 per cent and the quality of the information supplied wasn’t always of the highest quality.” 38 Britain by itself can’t do anything about tax havens The reality: • Many of the world’s tax havens are British Crown Dependencies or Overseas Territories, which we have the right to legislate for (Kilbrandon Report, 1973) • For example we overthrew the government in the Turks and Caicos Islands in 2009 • We could stop praising tepid international action and push, for example, for country by country reporting • We could stop making once-off agreements with tax havens – this only legitimises them and tax evasion, undermines reform efforts, and doesn’t help developing countries 39 A mass exodus of big business The reality: • Campaigners are pushing for country-by-country reporting to be included in international accounting standards, which are used in over 100 countries • Britain cracking down on crown dependencies and overseas territories is entirely independent from whether or not a business chooses to be domiciled in the UK • Companies want to access the UK market. The government could leverage this to increase transparency 40 Tax havens can stimulate investment The myth: • China and the UK do very well as a result of tax havens The reality: • Do we really want money that should be tax revenue in, for example, Mali? • Developing countries lose more via tax havens than they receive in aid & they allow corrupt governments to rob states • The best way for developing countries to grow their way out of poverty, increase life expectancy and reduce infant mortality is through public services and public investment in the infrastructure long-term business needs • Financial inflows to the City only benefit the 1% 41 Trickle down doesn’t work Average incomes in the UK £350,000 £300,000 £250,000 £200,000 Top 1% Top 10% £150,000 Bottom 90% £100,000 £50,000 £1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 Source: http://g-mond.parisschoolofeconomics.eu/topincomes/ 42 What about recent action by Cameron at the G8? What Cameron has done: • Companies registered in Britain would come under a legal obligation to obtain and hold adequate, accurate and current information on the ultimate owner who benefits from the company – and be required to place the information on a central register, maintained by Companies House • Tax authorities have a better chance of tracking the true ownership of trusts and shell companies • Britain expects the G8 to call on the OECD to implement a new agreement modelled on the US-led Financial Action Task Force on tax transparency, which is supported by 75 countries. The deal would lead to "automatic exchange", in which countries pass on tax details without a request having to be made 43 What about recent action by Cameron at the G8? The reality: • Companies House doesn’t have the resources to police compliance with the beneficial ownership register, so it will essentially be voluntary • Rumour has it that we may only get a requirement that companies know who their beneficial owners are if enquiry is made of them • Information won’t be publicly available • Need more info in order to properly determine the tax due • Developing countries must also benefit from automatic information exchange • Many tax departments, including in the UK, are hugely underresourced 44 Tax Planning, Tax Avoidance, Tax Evasion Tax Evasion • the efforts by taxpayers to mitigate taxes by illegal means. What can be defined as legal or illegal depends on the national laws. • the taxpayer avoids the payment of tax without avoiding the tax liability, so that he escapes the payment of tax that is unquestionably due according to the law of the taxing jurisdiction and even breaks the letter of the law. (Russo et. al, 2007) • An intention to avoid payment of tax where there is actual knowledge of liability. It usually involves deliberate concealment of the facts from the revenue authorities, and is illegal. (Rohatgi: 2007). • There is a correlation but still seems ambiguious that legal tax avoidance can push the public motive to evade the tax obligation (Neck and Schneider, 2011). • Philosophically, tax evasion also correlate with any other aspects of sociopolitical dimension (McGee,2007). For internal discussion only 46 Some common example of tax evasion • The failure by a taxable person to notify the tax authorities of his presence or activities in the country if he is carrying on taxable activities. • The failure to report the full amount of taxable income. • The deduction claims for expenses that have not been incurred, or which exceed the amounts that have been incurred. • Falsely claiming relief that is not due. • The failure to pay over to the tax authorities the tax properly due. • The departure from a country leaving taxes unpaid with no intention to paying them. • The failure to report items or sources of taxable income, profit or gains, where there is either a general obligation in the law to volunteer such information. For internal discussion only 47 Tax Avoidance • Tax avoidance is not tax evasion. Many have to try to formulate an exact definition but still unclear enough. • The art of dodging tax without breaking the law (Justice Reddy, McDowell & Co vs CTO, 1985) • The minimisation of one’s tax liability by taking advantage of legally available tax planning opportunities. (Black’s Law Dictionary). • An arrangement of a taxpayer’s affairs that is intended to reduce his liability and that although the arrangement could be strickly legal is usually in contradiction with the intent of the law it purports to follow. (OECD). For internal discussion only 48 What OECD said OECD just provides three elements of tax avoidance: (1) almost invariably there is present an element of artificially to it or, to put this another way, the various arrangements in a scheme do not have business or economic aims as their primary purpose’ (2) secrecy may also be a feature of modern avoidance: and (3) Tax avoidance often takes advantage of loopholes in the law or of applying legal provisions, for purposes for which they were not intended. OECD Model (2000) the prevention of tax avoidance is one of the purposes of double tax treaties. For internal discussion only 49 Tax Planning • Many countries make a distinction between acceptable tax avoidance and unacceptable tax avoidance. • Unacceptable TA is achieved by transactions that are genuine and legal but involve deceit or pretence or sham tax structures. (Lord Goff, Rohatgi:2007) • Contrary, Acceptable TA (tax planning) reduces the tax liability through the movement (or nonmovement) of persons, transactions or funds, or other activities that are intended by legislation also called tax mitigation. For internal discussion only 50 Categorizing Tax Planning Illegal Transaction Tax Evasion (Tax Fraud) Tax Avoidance (Fraus Legis) Legal Tax Planning For internal discussion only 51 Skema International Tax Planning Sumber: PriceWaterhouse Coopers, 2007. Google Double Irish / Dutch Sandwich II - 2009 Google (Pre-IPO) $ Capital Cost $ Sharing Agreement Buy-In Google Ireland Holdings Search + Advertising Technology – Europe, Middle East & Africa Google Double Irish / Dutch Sandwich II - 2009 Google (Pre-IPO) Sharing Cost Agreement Google Irelend Holdings Search + Advertising Technology Europe. Middle East & Africa Ireland European Affiliates & Customers Bermuda $$$ $$ Royalties License of Technology Google Netherlands BV (No Employees) Middle East Affiliates & Customers Africa Affiliates & Customers $$ Royalties $ Fees ($ Bilion Revenue 2009) Google Ireland Ltd 2000 Employees Sub-License of Technology Apple’s Scheme Apple Inc. (United States) Apple Operations International APPLE’S OFFSHORE SUBSIDIARIES Apple Retail Holding Europe (Ireland) Apple Retail Belgium Apple Retail France Apple Retail Germany Apple Retail Italia Apple Retail Netherlands Apple Retail Spain Apple Retail Switzerland Apple Retail UK Apple Distribution International (Ireland) Apple Singapore (Singapore) Apple Asia In-country distributors Apple Operations Europe Apple Sales International Country of Incorporation and Tax Residence These 3 subsidiaries are incorporated in Ireland, but have no country of tax residence 100 percent owned by Apple Inc., company that receivesthis is a holding dividends from most of Apple’s offshore affiliates. It has no physical presence and has never had any employees. A subsidiary of Apple Operations International, it had about 400 employees in 2012, and manufactured a line of specialty computers for sale in Europe. Contracted with third-party manufacturers in China to make Apple products which it then sold to Apple Distribution International. Paid little or no tax on $74 billion in profit made from 2009 to 2012. Apple’s Scheme - Continued Global Taxes Paid by ASI (Apple Sales International), 2009-2011 2011 2010 2009 Total $ 38 billion Pre-Tax Earning $ 22 billion $ 12 billion $ 4 billion Global Tax $ 10 million $ 7 million $ 4 million $ 21 million Tax Rate 0.05% 0.06% 0.1% 0.06% Foreign Base Company Sales Income Tax Avoided Tax Avoided 2011 $ 10 billion 2012 $ 25 billion Total $ 35 billion $ 3.5 billion $ 10 billion $ 9 billion $ 25 billion $ 12.5 billion $ 17 billion Vodafone’s Scheme HK Shareholder Cayman Co 1 (Cayman Island) Cayman Co 2 (Cayman Island) Maritius Co (Maritius) Hutchison Essar (India) Vodafone UK Sold Cayman Co 2 shares Vodafone Dutch Marks & Spencer Case No Consolidation Joint Taxation MARKS & SPENCER Subsidiaries are independent llegal and fiscal entities (separate) UK Company UK Branch Intermediary Netherlands Netherlands subsidiary Belgium subsidiary France subsidiary Germany subsidiary subsidiary Belgium France subsidiary Germany STARBUCKS’S SCHEME Starbucks Coffee Inti (USA) Rain City Dutch Partnership Enterald Dutch Partnership Royalty Royalty ALKI LP UK Royalty Starbucks Holding BV (Netherland) Starbucks Trading (Swiss) Starbucks UK Starbucks Mfg BV (Netherland) Kasus Indonesia (I) • Asian Agri Group diputus MA bersalah melakukan tax evasion dan dikenai denda Rp 2,5 T respondeat superior/vicarious responsibility. • Penerimaan Pajak masih di level 12,5% (tax ratio), bandingkan Korea (19%), Jepang (25%), rerata OECD 35%, Tanzania (16%). • Uang pajak sebagian besar masih digunakan untuk membiayai belanja birokrasi dan pelunasan utang, belanja sosial sifatnya residual. • Praktik penghindaran dan pengemplangan pajak hal yang jamak. • Warga yang ber-NPWP baru 22 juta UMKM 55 juta, penduduk potensial 110 juta. • Gayus mampu menyatukan lembaga penegak hukum dalam satu payung korupsi: Hakim Fenomena Gayus Mampu menyatukan lembaga penegak hukum dalam satu payung korupsi: Hakim Asnun, Jaksa Cyrus, Polisi Arafat dan Brigjen Edmond Ilyas, Penjaga Rutan Brimob, Petugas Imigrasi. Fenomena Regenerasi Koruptor Muda Kasus Indonesia (2) Kejahatan Kehutanan oleh Korporasi • 124 kasus kejahatan kehutanan dan kerugian negara lk. Rp 691 trilyun (ICW:2013), menjerat pidana : 37 operator lapangan, 20 direktur perusahaan, 9 kepala dinas, 4 polisi, 6 anggota DPR, 2 gubernur, 2 bupati. • Penghindaran atau manipulasi pajak Contoh Kasus: Kasus PT. Permata Hijau Sawit (2007-2008), Asian Agri Group (2002-2005), PT Wilmar Nabati Indonesia (2009-2010) • Pembiaran beroperasi tanpa izin Contoh Kasus: Beberapa perusahaan sawit seperti Sinar Mas, Wilmar, BGA/ IOI, Musim Mas, dan Astra Agro Lestari di Kalimantan Tengah tidak memiliki izin pelepasan kawasan hutan (Laporan Hasil Investigasi Kasus Korupsi Perkebunan, ICW, 2011: 9) Kejahatan Kehutanan oleh Korporasi • Alih fungsi kawasan hutan dan Pemanfaatan hasil hutan tanpa izin Contoh Kasus: Proyek Perkebunan Sawit Sejuta Hektar di Kalimantan Timur. Izin yang diberikan oleh Gubernur Kaltim Suwarna AF kepada 13 perusahaan sawit milik Surya Damai Group ternyata dimanipulasi. Citra satelit membuktikan hanya 3 dari 13 perusahaan yang menanam sawit. Sisanya diketahui hanya mengeksploitasi hutan. • Perolehan izin pemanfaatan kawasan dan hasil hutan secara tidak sah Contoh Kasus: Berdasarkan Investigasi, untuk mendapatkan 1 (satu) izin lokasi di Kabupaten Seruyan , Pengusaha perkebunan dipungut biaya Rp. 4 milyar. Selain itu, ada pula suap berdasarkan luas perkebunan sawit yang dimintakan izin. Sawit Watch menyebutkan bahwa biaya penerbitan izin lokasi untuk setiap hektar kebun sawit Birokrasi kita? • Berjumlah lk. 4 juta pegawai pusat dan daerah. • Mengurus Rp 1.657 trilyun/tahun. • Menguras: Rp 241 trilyun untuk belanja birokrasi. Rp 518 trilyun transfer ke daerah, dan 50% dialokasikan untuk belanja pegawai. Rp 171 trilyun untuk cicilan pokok dan bunga utang. Rp 299 trilyun untuk subsidi, Rp 143 trilyun subsidi BBM. • Indeks Gini 0.41, semakin timpang. Perbandingan Indeks Pembangunan Manusia 2013 TRANSFER PRICING Main Issues: • • • • • • • • • Is Arm’s Length Principle work properly? The lack of comparability The problem of cartel or oligopoly The massive use of intangibles Cost Contibution Arrangement New challenge: Formulary Apportionment Country-by-Country Reporting Common Consilidated Corporate Tax Base VAT integration Unitary Taxation approach of the EU CCCTB Source: Erika Siu,2013 Apportionment formula in the EU CCCTB • Art. 86: capital, labour and sales. The labour factor includes wages and employees at equal weights. Unitary Taxation approaches of the US states Source: Erika Siu,2013 Recent TP Development: Global Transfer Pricing Arena United Nations Multinational Enterprises Tax Practitioners OECD Tax Court Government Developing Countries Multinational forums NGOs Recent TP Development: Global Change the principle Arm;s length principle Limitation in application Global Formulary Apportionment Simplification measures Threshold, saf e harbour, etc Relaxing the assumption Hypothetical arm’s length Alternative practical applications Alternative method, etc Problem of Value Creation Business Restructuring Local intangibles/ market premium Intangibles Location savings Cost Contribution Arrangement Definition? Identification? Benefit test? Comparables? Transfer pricing method? WHAT WE CAN DO? 76 BEPS Base Erosion and Profit Shifting And BEPS Action Plan 77 Data on Foreign Direct Investments •It emerges that in 2010 Barbados, Bermuda and the British Virgin Islands received more FDIs (combined 5.11% of global FDIs) than Germany (4.77%) or Japan (3.76%). these three jurisdictions made more investments into the world (combined 4.54%) than Germany (4.28%). •in 2010 the British Virgin Islands were the second largest investor into China (14%) after Hong Kong (45%) and before the United States (4%). Bermuda appears as the third largest investor in Chile (10%). •Mauritius is the top investor country into India 24%, while Cyprus (28%), the British Virgin Islands (12%), Bermuda (7%) and the Bahamas (6%) are among the top five investors into Russia. •Special purpose entities (SPE´s) with no or few employees, little or no physical presence in the host economy, whose assets and liabilities represent investments in or from other countries, whose core business consists of group financing or holding activities. For example: Netherlands, Luxembourg, Austria and Hungary. 78 Competitiveness and taxation •For a corporation, being competitive means to be able to sell the best products at the best price, so as to increase its profits and shareholder value. that investments will be made where profitability is the highest and that tax is one of the factors. •International competitiveness, a relatively low corporate tax burden. •The four key factors are: • (i) no or low effective tax rate; • (ii) ring-fencing of the regime; • (iii) lack of transparency; • (iv) lack of effective exchange of information. 79 Competitiveness and taxation •The other eight factors are: • (i) an artificial definition of the tax base; • (ii) failure to adhere to international transfer pricing principles; • (iii) foreign source income exempt from residence country taxation; • (iv) negotiable tax rate or tax base; • (v) existence of secrecy provisions; • (vi) access to a wide network of tax treaties; • (vii) the regime is promoted as a tax minimisation vehicle; • (viii) the regime encourages purely tax-driven operations or arrangements. •Tax transparency •More than 800 agreements that provide for the exchange of information in tax. •110 peer reviews have been launched and 88 peer review reports have been completed and published. •Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA). 80 Addressing Base Erosion and Profit Shifting •Base erosion constitutes a serious risk to • tax revenues, • tax sovereignty and • tax fairness for OECD member countries and non-members alike. A significant source of base erosion is profit shifting. 81 Addressing concerns related to base erosion and profit shifting •Key pressure areas, includes: International mismatches in entity and instrument characterization including hybrid mismatch arrangements and arbitrage; Application of treaty concepts to profits derived from the delivery of digital goods and services; The tax treatment of related party debt-financing, captive insurance and other inter-group financial transactions; 82 Addressing concerns related to base erosion and profit shifting Key pressure areas Transfer pricing, in particular in relation to the shifting of risks and intangibles, the artificial splitting of ownership of assets between legal entities within a group, and transactions between such entities that would rarely take place between independents; The effectiveness of anti-avoidance measures, in particular GAARs, CFC regimes, thin capitalisation rules and rules to prevent tax treaty abuse; and The availability of harmful preferential regimes. 83 ACTION 1 Address the tax challenges of the digital economy • Identify the main difficulties that the digital economy poses for the application of existing international tax rules and develop detailed options to address these difficulties, taking a holistic approach and considering both direct and indirect taxation. • Issues to be examined include, but are not limited to, • the ability of a company to have a significant digital presence in the economy of another country without being liable to taxation due to the lack of nexus under current international rules, • the attribution of value created from the generation of marketable location-relevant data through the use of digital products and services, • the characterization of income derived from new business models, • the application of related source rules, and • how to ensure the effective collection of VAT/GST with respect to the cross-border supply of digital goods and services. • Such work will require a thorough analysis of the various business models in this sector. • Expected output: Report identifying issues raised by the digital economy and possible actions to address them. • Deadline: September 2014 84 ACTION 2 Neutralise the effects of hybrid mismatch arrangements • • Hybrid mismatch arrangements can be used to achieve unintended double non-taxation or long-term tax deferral by, for instance, creating two deductions for one borrowing, generating deductions without corresponding income inclusions, or misusing foreign tax credit and participation exemption regimes. Develop model treaty provisions and recommendations regarding the design of domestic rules to neutralize the effect (e.g. double non-taxation, double deduction, long-term deferral) of hybrid instruments and entities. This may include: • (i) changes to the OECD Model Tax Convention to ensure that hybrid instruments and entities (as well as dual resident entities) are not used to obtain the benefits of treaties unduly; • (ii) domestic law provisions that prevent exemption or non-recognition for payments that are deductible by the payor; • (iii) domestic law provisions that deny a deduction for a payment that is not includible in income by the recipient (and is not subject to taxation under controlled foreign company (CFC) or similar rules); • (iv) domestic law provisions that deny a deduction for a payment that is also deductible in another jurisdiction; and • (v) where necessary, guidance on co-ordination or tie-breaker rules if more than one country seeks to apply such rules to a transaction or structure. Special attention should be given to the interaction between possible changes to domestic law and the provisions of the OECD Model Tax Convention. This work will be co-ordinated with the work on interest expense deduction limitations, the work on CFC rules, and the work on treaty shopping. 85 ACTION 2 Neutralise the effects of hybrid mismatch arrangements • Expected output: – Changes to the Model Tax Convention – Recommendations regarding the design of domestic rules • Deadline: – September 2014 86 ACTION 3 Strengthen CFC rules • CFC and other antideferral rules have been introduced in many countries to address routing income of a resident enterprise through the non-resident affiliate. • However, the CFC rules of many countries do not always counter BEPS in a comprehensive manner. While CFC rules in principle lead to inclusions in the residence country of the ultimate parent, they also have positive spillover effects in source countries because taxpayers have no (or much less of an) incentive to shift profits into a third, low-tax jurisdiction • Develop recommendations regarding the design of controlled foreign company rules. This work will be co-ordinated with other work as necessary • Expected output: Recommendations regarding the design of domestic rules. • Deadline: September 2015 87 ACTION 4 Limit base erosion via interest deductions and other financial payments • The deductibility of interest expense can give rise to double non-taxation in both the inbound and outbound investment scenarios. • From an inbound perspective, the concern regarding interest expense deduction is primarily with lending from a related entity that benefits from a low-tax regime, to create excessive interest deductions for the issuer without a corresponding interest income inclusion by the holder. The result is that the interest payments are deducted against the taxable profits of the operating companies while the interest income is taxed favourably or not at all at the level of the recipient. • From an outbound perspective, a company may use debt to finance the production of exempt or deferred income, thereby claiming a current deduction for interest expense while deferring or exempting the related income. Rules regarding the deductibility of interest expense therefore should take into account that the related interest income may not be fully taxed or that the underlying debt may be used to inappropriately reduce the earnings base of the issuer or finance deferred or exempt income. • Related concerns are raised by deductible payments for other financial transactions, such as financial and performance guarantees, derivatives, and captive and other insurance arrangements, particularly in the context of transfer pricing. 88 ACTION 4 Limit base erosion via interest deductions and other financial payments Develop recommendations regarding best practices in the design of rules to prevent base erosion through the use of interest expense, for example • through the use of related-party and third-party debt to achieve excessive interest deductions or • to finance the production of exempt or deferred income, and • other financial payments that are economically equivalent to interest payments. The work will evaluate the effectiveness of different types of limitations. In connection with and in support of the foregoing work, transfer pricing guidance will also be developed regarding the pricing of related party financial transactions, including financial and performance guarantees, derivatives (including internal derivatives used in intrabank dealings), and captive and other insurance arrangements. The work will be co-ordinated with the work on hybrids and CFC rules. • Expected output: – Recommendations regarding the design of domestic rules. – Changes to the TP Guidelines • Deadline: – September 2015 89 ACTION 5 Counter harmful tax practices more effectively, taking into account transparency and substance Revamp the work on harmful tax practices with a priority on • improving transparency, • including compulsory spontaneous exchange on rulings related to preferential regimes, and • on requiring substantial activity for any preferential regime. It will take a holistic approach to evaluate preferential tax regimes in the BEPS context. It will engage with non-OECD members on the basis of the existing framework and consider revisions or additions to the existing framework • Expected output: – Finalize review of member country regimes (Sep 2014) – Strategy to expand participation to non-OECD members (Sep 2015) – Revision of existing criteria (Dec 2015) 90 ACTION 6 Prevent treaty abuse • Current rules work well in many cases, but they need to be adapted to prevent BEPS that results from the interactions among more than two countries and to fully account for global value chains. • The interposition of third countries in the bilateral framework established by treaty partners has led to the development of schemes such as • low-taxed branches of a foreign company, • conduit companies, and • the artificial shifting of income through transfer pricing arrangements. FDI figures show the magnitude of the use of certain regimes to channel investments and intra-group financing from one country to another through conduit structures. In order to preserve the intended effects of bilateral relationships, the rules must be modified to address the use of multiple layers of legal entities inserted between the residence country and the source country • Existing domestic and international tax rules should be modified in order to more closely align the allocation of income with the economic activity that generates that income 91 ACTION 7 Prevent the artificial avoidance of PE status • In many countries, the interpretation of the treaty rules on agency-PE allows contracts for the sale of goods belonging to a foreign enterprise to be negotiated and concluded in a country by the sales force of a local subsidiary of that foreign enterprise without the profits from these sales being taxable to the same extent as they would be if the sales were made by a distributor. • In many cases, this has led enterprises to replace arrangements under which the local subsidiary traditionally acted as a distributor by “commissionnaire arrangements” with a resulting shift of profits out of the country where the sales take place without a substantive change in the functions performed in that country. • Develop changes to the definition of PE to prevent the artificial avoidance of PE status in relation to BEPS, including through the use of commissionaire arrangements and the specific activity exemptions. Work on these issues will also address related profit attribution issues. • Expected output: Changes in the Model Tax Convention • Deadline: Sep 2015 92 ACTION 8, 9 and 10 Assure that transfer pricing outcomes are in line with value creation • In some instances, multinationals have been able to use and/or misapply arm’s length principle to separate income from the economic activities that produce that income and to shift it into low-tax environments. • This most often results from • transfers of intangibles and other mobile assets for less than full value, • the over-capitalisation of lowly taxed group companies and • contractual allocations of risk to low-tax environments in transactions that would be unlikely to occur between unrelated parties • Rather than seeking to replace the current transfer pricing system, the best course is to directly address the flaws in the current system, in particular with respect to returns related to intangible assets, risk and overcapitalisation. Nevertheless, special measures, either within or beyond the arm’s length principle, may be required 93 ACTION 8, 9 and 10 Assure that transfer pricing outcomes are in line with value creation Action 8 – Intangibles • Develop rules to prevent BEPS by moving intangibles among group members. This will involve: (i) adopting a broad and clearly delineated definition of intangibles; (ii) ensuring that profits associated with the transfer and use of intangibles are appropriately allocated in accordance with (rather than divorced from) value creation; (iii) developing transfer pricing rules or special measures for transfers of hard-tovalue intangibles; and (iv) updating the guidance on cost contribution arrangements. Action 9 – Risks and capital • Develop rules to prevent BEPS by transferring risks among, or allocating excessive capital to, group members. • This will involve adopting transfer pricing rules or special measures to ensure that inappropriate returns will not accrue to an entity solely because it has contractually assumed risks or has provided capital. • The rules to be developed will also require alignment of returns with value creation. • This work will be co-ordinated with the work on interest expense deductions and other financial payments. 94 ACTION 8, 9 and 10 Assure that transfer pricing outcomes are in line with value creation Action 10 – Other high-risk transactions • Develop rules to prevent BEPS by engaging in transactions which would not, or would only very rarely, occur between third parties. • This will involve adopting transfer pricing rules or special measures to: (i) clarify the circumstance in which transactions can be recharacterised; (ii) clarify the application of transfer pricing methods, in particular profit splits, in the context of global value chains; and (iii) provide protection against common types of base eroding payments, such as management fees and head office expenses. • Expected output: Changes to the Transfer Pricing Guidelines and possibly to the Model Tax Convention • Deadline: Sep 2015 95 ACTION 11 Establish methodologies to collect and analyse data on BEPS and the actions to address it • Transparency, certaintay and predictability • Data collection on BEPS should be improved. Taxpayers should disclose more targeted information about their tax planning strategies, and transfer pricing documentation requirements should be less burdensome and more targeted • There are several studies and data indicating that there is an increased disconnect between the location where value creating activities and investment take place and the location where profits are reported for tax purposes • Therefore, the objective is to develop techniques, which look at measures of the allocation of income across jurisdictions relative to measures of value creating activities 96 ACTION 11 Establish methodologies to collect and analyse data on BEPS and the actions to address it • Develop recommendations regarding indicators of the scale and economic impact of BEPS and ensure that tools are available to monitor and evaluate the effectiveness and economic impact of the actions taken to address BEPS on an ongoing basis. • This will involve developing an economic analysis of the scale and impact of BEPS (including spillover effects across countries) and actions to address it. • The work will also involve assessing a range of existing data sources, identifying new types of data that should be collected, and developing methodologies based on both aggregate (e.g. FDI and balance of payments data) and micro-level data (e.g. from financial statements and tax returns), taking into consideration the need to respect taxpayer confidentiality and the administrative costs for tax administrations and businesses • Expected output: Recommendations regarding the data to be collected and methodologies to analyse them • Deadline: Sep 2015 97 ACTION 12 Require taxpayers to disclose their aggresive tax planning arrangements • Comprehensive and relevant information on tax planning strategies is often unavailable to tax administrations. Yet the availability of timely, targeted and comprehensive information is essential to enable governments to quickly identify risk areas • Develop recommendations regarding the design of mandatory disclosure rules for aggressive or abusive transactions, arrangements, or structures, taking into consideration the administrative costs for tax administrations and businesses and drawing on experiences of the increasing number of countries that have such rules. • The work will use a modular design allowing for maximum consistency but allowing for country specific needs and risks. • One focus will be international tax schemes, where the work will explore using a wide definition of “tax benefit” in order to capture such transactions. The work will be coordinated with the work on co-operative compliance. It will also involve designing and putting in place enhanced models of information sharing for international tax schemes between tax administrations. • Expected output: Recommendations regarding the data to be collected and methodologies to analyse them • Deadline: Sep 2015 98 ACTION 13 Re-examine transfer pricing documentation • In many countries, tax administrations have little capability of developing a “big picture” view of a taxpayer’s global value chain. • In this respect, it is important that adequate information about the relevant functions performed by other members of the MNE group in respect of intra-group services and other transactions is made available to the tax administration • Develop rules regarding transfer pricing documentation to enhance transparency for tax administration, taking into consideration the compliance costs for business. •The rules to be developed will include a requirement that MNE’s provide all relevant governments with needed information on their global allocation of the income, economic activity and taxes paid among countries according to a common template • Expected output: Changes to Transfer Pricing Guidelines and Recommendations regarding the design of domestic rules • Deadline: Sep 2014 99 ACTION 14 Make dispute resolution mechanisms more effective • Ensure certainty and predictability for business • Improve the effectiveness of the mutual agreement procedure (MAP). For this purposes, it will be supplemented the existing MAP provisions in tax treaties with a mandatory and binding arbitration provision • Develop solutions to address obstacles that prevent countries from solving treaty-related disputes under MAP, including the absence of arbitration provisions in most treaties and the fact that access to MAP and arbitration may be denied in certain cases. • Expected output: Changes to Model Tax Convention • Deadline: Sep 2015 100 ACTION 15 Develop a multilateral instrument Expected output: • • Report identifying relevant public international law and tax issues (Sep 2014) Develop a multilateral instrument (Dec 2015) • Some actions will likely result in • recommendations regarding domestic law provisions, • changes to the Commentary to the OECD Model Tax Convention • Transfer Pricing Guidelines. • changes to the OECD Model Tax Convention. This is for example the case for the introduction of – an anti-treaty abuse provision, –changes to the definition of permanent establishment, –changes to transfer pricing provisions and –the introduction of treaty provisions in relation to hybrid mismatch arrangements • A multilateral instrument to amend bilateral treaties is a promising way forward in this respect • Analyse the tax and public international law issues related to the development of a multilateral instrument to enable jurisdictions that wish to do so to implement measures developed in the course of the work on BEPS and amend bilateral tax treaties. •On the basis of this analysis, interested Parties will develop a multilateral instrument designed to provide an innovative approach to international tax matters, reflecting the rapidly evolving nature of the global economy and the need to adapt quickly to this evolution. 101 TAX PLANNING, TAX AVOIDANCE, AND TAX EVASION General Concepts Tax Evasion, Tax Avoidance, Tax Planning Tax Avoidance vs Tax Evasion Practically, it is unclear definiton and sometimes very depend on the tax authority interpretation. It seems as a nuance that need to be scrutinized into details. There are some approaches to tax evasion concept: 1. Economic approach 2. Legal approach 3. Political approach 4. Philosophical approach • Many literatures and experts usually use economic/legal approach and just to calculate the loss of revenue and penalties. 103 Tax Evasion • the efforts by taxpayers to mitigate taxes by illegal means. What can be defined as legal or illegal depends on the national laws. • the taxpayer avoids the payment of tax without avoiding the tax liability, so that he escapes the payment of tax that is unquestionably due according to the law of the taxing jurisdiction and even breaks the letter of the law. (Russo et. al, 2007) • An intention to avoid payment of tax where there is actual knowledge of liability. It usually involves deliberate concealment of the facts from the revenue authorities, and is illegal. (Rohatgi: 2007). • There is a correlation but still seems ambiguious that legal tax avoidance can push the public motive to evade the tax obligation (Neck and Schneider, 2011). • Philosophically, tax evasion also correlate with any other aspects of sociopolitical dimension (McGee,2007). 104 Some common example of tax evasion • The failure by a taxable person to notify the tax authorities of his presence or activities in the country if he is carrying on taxable activities. • The failure to report the full amount of taxable income. • The deduction claims for expenses that have not been incurred, or which exceed the amounts that have been incurred. • Falsely claiming relief that is not due. • The failure to pay over to the tax authorities the tax properly due. • The departure from a country leaving taxes unpaid with no intention to paying them. • The failure to report items or sources of taxable income, profit or gains, where there is either a general obligation in the law to volunteer such information. 105 Tax Avoidance • Tax avoidance is not tax evasion. Many have to try to formulate an exact definition but still unclear enough. • The art of dodging tax without breaking the law (Justice Reddy, McDowell & Co vs CTO, 1985) • The minimisation of one’s tax liability by taking advantage of legally available tax planning opportunities. (Black’s Law Dictionary). • An arrangement of a taxpayer’s affairs that is intended to reduce his liability and that although the arrangement could be strickly legal is usually in contradiction with the intent of the law it purports to follow. (OECD). 106 What OECD said OECD just provides three elements of tax avoidance: (1) almost invariably there is present an element of artificially to it or, to put this another way, the various arrangements in a scheme do not have business or economic aims as their primary purpose’ (2) secrecy may also be a feature of modern avoidance: and (3) Tax avoidance often takes advantage of loopholes in the law or of applying legal provisions, for purposes for which they were not intended. OECD Model (2000) the prevention of tax avoidance is one of the purposes of double tax treaties. 107 Tax Planning • Many countries make a distinction between acceptable tax avoidance and unacceptable tax avoidance. • Unacceptable TA is achieved by transactions that are genuine and legal but involve deceit or pretence or sham tax structures. (Lord Goff, Rohatgi:2007) • Contrary, Acceptable TA (tax planning) reduces the tax liability through the movement (or nonmovement) of persons, transactions or funds, or other activities that are intended by legislation also called tax mitigation. 108 Categorizing Tax Planning Illegal Transaction Tax Evasion (Tax Fraud) Tax Avoidance (Fraus Legis) Legal Tax Planning 109 Skema International Tax Planning Sumber: PriceWaterhouse Coopers, 2007. Google Double Irish / Dutch Sandwich II - 2009 Google (Pre-IPO) $ Capital Cost $ Sharing Agreement Buy-In Google Ireland Holdings Search + Advertising Technology – Europe, Middle East & Africa Google Double Irish / Dutch Sandwich II - 2009 Google (Pre-IPO) Sharing Cost Agreement Google Irelend Holdings Search + Advertising Technology Europe. Middle East & Africa Ireland European Affiliates & Customers Bermuda $$$ $$ Royalties License of Technology Google Netherlands BV (No Employees) Middle East Affiliates & Customers Africa Affiliates & Customers $$ Royalties $ Fees ($ Bilion Revenue 2009) Google Ireland Ltd 2000 Employees Sub-License of Technology Apple’s Scheme Apple Inc. (United States) Apple Operations International APPLE’S OFFSHORE SUBSIDIARIES Apple Retail Holding Europe (Ireland) Apple Retail Belgium Apple Retail France Apple Retail Germany Apple Retail Italia Apple Retail Netherlands Apple Retail Spain Apple Retail Switzerland Apple Retail UK Apple Distribution International (Ireland) Apple Singapore (Singapore) Apple Asia In-country distributors Apple Operations Europe Apple Sales International Country of Incorporation and Tax Residence These 3 subsidiaries are incorporated in Ireland, but have no country of tax residence 100 percent owned by Apple Inc., company that receivesthis is a holding dividends from most of Apple’s offshore affiliates. It has no physical presence and has never had any employees. A subsidiary of Apple Operations International, it had about 400 employees in 2012, and manufactured a line of specialty computers for sale in Europe. Contracted with third-party manufacturers in China to make Apple products which it then sold to Apple Distribution International. Paid little or no tax on $74 billion in profit made from 2009 to 2012. Apple’s Scheme - Continued Global Taxes Paid by ASI (Apple Sales International), 2009-2011 2011 2010 2009 Total $ 38 billion Pre-Tax Earning $ 22 billion $ 12 billion $ 4 billion Global Tax $ 10 million $ 7 million $ 4 million $ 21 million Tax Rate 0.05% 0.06% 0.1% 0.06% Foreign Base Company Sales Income Tax Avoided Tax Avoided 2011 $ 10 billion 2012 $ 25 billion Total $ 35 billion $ 3.5 billion $ 10 billion $ 9 billion $ 25 billion $ 12.5 billion $ 17 billion Vodafone’s Scheme HK Shareholder Cayman Co 1 (Cayman Island) Cayman Co 2 (Cayman Island) Maritius Co (Maritius) Hutchison Essar (India) Vodafone UK Sold Cayman Co 2 shares Vodafone Dutch Marks & Spencer Case No Consolidation Joint Taxation MARKS & SPENCER Subsidiaries are independent llegal and fiscal entities (separate) UK Company UK Branch Intermediary Netherlands subsidiary Belgium Netherlands subsidiary France subsidiary Germany subsidiary subsidiary Belgium France subsidiary Germany STARBUCKS’S SCHEME Starbucks Coffee Inti (USA) Rain City Dutch Partnership Enterald Dutch Partnership Royalty Royalty ALKI LP UK Royalty Starbucks Holding BV (Netherland) Starbucks Trading (Swiss) Starbucks UK Starbucks Mfg BV (Netherland) Skema Anti Penghindaran Pajak (Anti Tax Avoidance) Pengaturan CFC Rule di Indonesia PT A Tuan B INDONESIA 40% Q X Ltd. Laba setelah Pajak 2012 Rp.1.000.000.000,00 40% Pembiayaan dengan Saham DIVIDEN Perusahaan Induk Laba Operasional 100 Negara A Saham Negara B 1000 Anak Perusahaan Laba Operasional 50 Pembiayaan dengan Kombinasi Utang dan Saham Perusahaan Induk Laba Operasional 100 Penghasilan Bunga 40 140 Bunga 5% Dividen Negara A Saham Negara B 200 Anak Perusahaan Laba Operasional 50 Biaya Bunga 40 10 Utang 800 Skema Interest Stripping X Ltd. Negara A 25% Utang (hubungan 1000 istimewa) Indonesia PT Y Remunerasi 10% laba tanpa batas waktu Conduit Company sebagai Bentukan PT A Y Co. Negara B P3B negara A dan negara B : 100 % Tarif PPh Dividen 0% P3B negara B dan Indonesia : Z Co. 100 % Negara A P3B negara A dan Indonesia : Tarif PPh Dividen : 10% Indonesia PT X Tarif PPh Dividen 15% Tanpa Conduit Company Rule I Z Co. Negara A 100 % Indonesia Dividen PPh 10% PT X Dengan Conduit Company Rule I Y Co. Negara B 100 % Indonesia PT X Dividen PPh 15% Skema Conduit Company Rule II Y Co. Negara B 100 % X Ltd. 95 % Negara A Indonesia PT X Tanpa Conduit Company Rule II Y Co. Negara B 100 % Negara A Penjualan 100% saham X Ltd. Ke PT Z PT Z PT X Dengan Conduit Company Rule II Y Co. Negara B 100 % Negara A PT X Penjualan 100% saham X Ltd. Ke PT Z PT Z Skema International Hiring-Out of Labor X Ltd. (user) e 25% (hubungan istimewa) Melakukan pekerjaan di negara A Negara A Indonesia PT A (hirer) e Skema Hubungan Istimewa di Indonesia PT A 25% 50% PT B 25% 50% PT C PT D