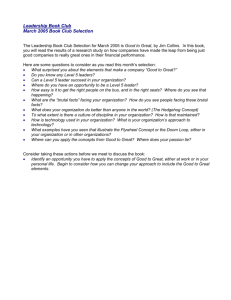

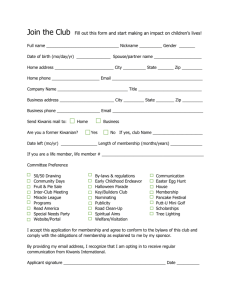

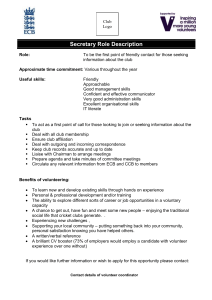

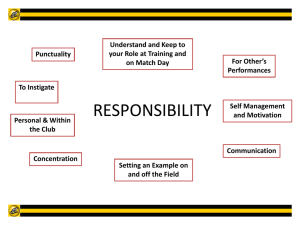

Club Marketing

advertisement