Psychological Analysis - APE LIT Survival Guide

advertisement

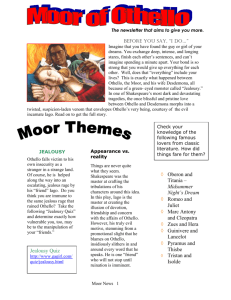

The themes of jealousy, pride, and revenge have consistently interested scholars throughout Othello's critical history. With the development of psychoanalysis and its application to literary characters, twentieth-century critics have expanded on earlier interpretations of the play's three primary characters and suggested new explanations and motivations for their actions. Interpretations of Othello's character are often negative, focusing on his pride and jealousy as fatal flaws. Robert Hapgood (1966) has described Othello as excessively self-righteous and judgemental and argued that the play should make viewers wary of their own tendencies to judge. Focusing his analysis on the play's structure, Larry S. Champion (1973) has written that Shakespeare's "economy of design" centers attention on the "destruction of character resulting from a lack of self-knowledge, … which is the consequence of the vanity of one's insistence on viewing everything through the distorting medium of his [Othello's] own self-importance." Othello's egocentricity, Champion argued, rendered him exceedingly susceptible to jealousy and fabrications concerning his wife. Other scholars have employed psychoanalytic theories in their interpretations of Othello's character. Stephen Reid (1968), for example, has suggested an unresolved Oedipus complex as the source of Othello's delusional jealousy. Reid argued that Othello's mother rejected him for his father and this "treachery" on her part led him to reject women. Similarly, Robert Rogers (1969) has viewed Othello as a composite character composed of conflicting tendencies and has identified the Oedipus complex as a primary factor in explaining Othello's behavior. Opinion on the character of Desdemona has been sharply divided. While some critics have depicted her as an innocent, passive victim, others have described her as wanton, domineering, and at least partially responsible for her fate. Robert Dickes (1970) has contended that Desdemona is a domineering character who actively strives to achieve her ends and harbors an unconscious death-wish. As evidence of this nature, Dickes observes her wooing of Othello and her efforts to have Cassio reinstated and attributes the motivation for her actions—which ultimately lead to her death—to the Oedipus complex. Desdemona, he argued, "chose as a love object a man representative of her father. Forced by the prompting of her superego, she then atoned for this incestuous choice by behaving in such a way as to make Othello even more certain in his jealousy." W. D. Adamson (1980), however, has interpreted Desdemona's "ambiguous-looking behavior" as a sign of her innocence and positive moral standing. He maintained that Othello is the "tragedy of an unworldly woman calumniated and murdered by … a sex-obsessed tyrant who insists on thinking the worst as she insists on the best." Other scholars who have centered their attention on Desdemona have sought to shift interpretation of the play away from the tragedy of an individual. Julian C. Rice (1974) has suggested that Desdemona resembles Othello more than she transcends him and that the play is primarily a tragedy of human nature, while Irene G. Dash (1981) has asserted that Othello is a study of the complexities of marriage. One of the play's most perplexing characters, Iago's actions appear to lack a clear sense of motive. A dominant theme in Othello criticism, therefore, has been an effort to explain Iago's motivations. Some scholars, such as Daniel Stempel (1969), have conceded that Shakespeare's text does not offer a solution to the question of Iago's motives and was never intended to do so. Stempel has maintained that "Iago embodies the mystery of the evil will, an enigma which Shakespeare strove to realize, not to analyze." Many commentators, however, have contended that simply labeling Iago as the personification of evil does not do justice to Shakespeare's skills of character development. Fred West (1978), for instance, has suggested that Shakespeare created a profound and accurate portrait of a psychopath in Iago. As such, West continued, "Iago's only motivation is an immature urge toward instant pleasure." Gordon Ross Smith (1959) has maintained that Iago's" actions and his hatred of Desdemona—whose marriage usurped his place in Othello's affections—are attributable to his repressed homosexual feelings toward Othello and Cassio. Other critics, such as Leslie Y. Rabkin and Jeffrey Brown (1973), have argued that Iago is a sadist who suffers from a sense of hopelessness and self-contempt and that he attempts to deal with these emotions by projecting his feelings onto others and working to destroy their sense of peace and joy. "Tragedy resides in the heart of character," Smith concluded. "Its inescapable quality is justified by what responsibility each person ultimately carries for what he has become, but its tragic qualities derive from the helplessness of people to escape from what they essentially are." Beginning with the opening lines of the play, Othello remains at a distance from much of the action that concerns and affects him. Roderigo and Iago refer ambiguously to a “he” or “him” for much of the first scene. When they begin to specify whom they are talking about, especially once they stand beneath Brabanzio’s window, they do so with racial epithets, not names. These include “the Moor” (I.i.57), “the thick-lips” (I.i.66), “an old black ram” (I.i.88), and “a Barbary horse” (I.i.113). Although Othello appears at the beginning of the second scene, we do not hear his name until well into Act I, scene iii (I.iii.48). Later, Othello’s will be the last of the three ships to arrive at Cyprus in Act II, scene i; Othello will stand apart while Cassio and Iago supposedly discuss Desdemona in Act IV, scene i; and Othello will assume that Cassio is dead without being present when the fight takes place in Act V, scene i. Othello’s status as an outsider may be the reason he is such easy prey for Iago. Although Othello is a cultural and racial outsider in Venice, his skill as a soldier and leader is nevertheless valuable and necessary to the state, and he is an integral part of Venetian civic society. He is in great demand by the duke and senate, as evidenced by Cassio’s comment that the senate “sent about three several quests” to look for Othello (I.ii.46). The Venetian government trusts Othello enough to put him in full martial and political command of Cyprus; indeed, in his dying speech, Othello reminds the Venetians of the “service” he has done their state (V.ii.348). Those who consider Othello their social and civic peer, such as Desdemona and Brabantio, nevertheless seem drawn to him because of his exotic qualities. Othello admits as much when he tells the duke about his friendship with Brabantio. He says, -“[Desdemona’s] father loved me, oft invited me, / Still questioned me the story of my life / From year to year” (I.iii.127–129). Othello is also able to captivate his peers with his speech. The duke’s reply to Othello’s speech about how he wooed Desdemona with his tales of adventure is: “I think this tale would win my daughter too” (I.iii.170). Othello sometimes makes a point of presenting himself as an outsider, whether because he recognizes his exotic appeal or because he is self-conscious of and defensive about his difference from other Venetians. For example, in spite of his obvious eloquence in Act I, scene iii, he protests, “Rude am I in my speech, / And little blessed with the soft phrase of peace” (I.iii.81– 82). While Othello is never rude in his speech, he does allow his eloquence to suffer as he is put under increasing strain by Iago’s plots. In the final moments of the play, Othello regains his composure and, once again, seduces both his onstage and offstage audiences with his words. The speech that precedes his suicide is a tale that could woo almost anyone. It is the tension between Othello’s victimization at the hands of a foreign culture and his own willingness to torment himself that makes him a tragic figure rather than simply Iago’s ridiculous puppet.