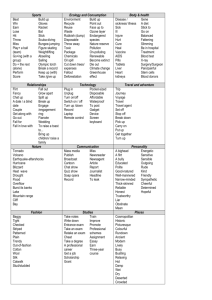

Computer Crimes Outline

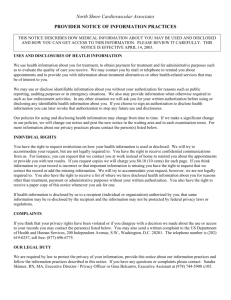

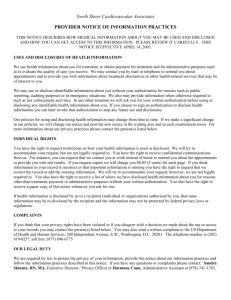

advertisement