29124,"the missouri compromise attempted to",10,,,110,http://www.123helpme.com/view.asp?id=23329,2.5,134000,"2016-02-23 09:56:58"

advertisement

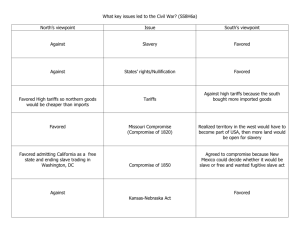

J. Calvin Schermerhorn 22 June 2002 AmericanPresident.org Summer Assignments: Phase I Event: Crittenden Compromise (Buchanan administration, 1860) On December 18, 1860 Democratic Senator John J. Crittenden attempted a lastditch compromise to forestall widespread southern secession. Crittenden proposed amending the Constitution to permit and protect slavery in territories south of the 36 30 Missouri Compromise line and guarantee that slavery would be left undisturbed in states where it existed already. That territory would include both lands already in U.S. possession and any future territory the U.S. might acquire. Crittenden wanted southerners to give up their theoretical rights guaranteed by the Dred Scott decision, which allowed take slavery north of 36 30. The compromise would give slaveowners a federally protected right to own slaves south of the Missouri Compromise line. Crittenden thought that that provision would allay fears that Republicans wanted to isolate slave states and destroy slavery everywhere. Among Democrats in the upper South, the Crittenden proposal was popular. Both James Buchanan and his bitter rival Stephen A. Douglas endorsed it. Less than a year earlier, Douglas had alienated southern Democrats by opposing a territorial slave code. To many in the upper South, it was the minimum acceptable compromise to avoid disunion. Many unionists were skeptical, and nobody could endorse Crittenden’s proposal without sacrificing their earlier views and offending a core constituency. It placated those who thought that the Missouri Compromise line worked, and it would avoid both the constitutional question of the 36 30 line and vacate the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision by amending the Constitution. Recalling that some southern Unionists had refused to support the Kansas-Nebraska Act and Lecompton Constitution, Horace Maynard of Tennessee thought it was reasonable to ask Republicans to sign up for the Crittenden Compromise and save the Union. Republicans proved to be just as ardent in their defense of free soil as many in the lower South were of perpetual and ever-expanding slavery. Republican Salmon P. Chase would not “consent to surrender a principle” that voters in the North had endorsed in the last election. Abraham Lincoln considered Crittenden’s proposal and indeed all such proposals “dishonorable and treacherous.” Republicans suspected that Crittenden’s compromise would sanction new slave territories in the Caribbean, which went well beyond the scope of the Missouri Compromise. That applied only to the Louisiana Purchase territory, and southern Unionists refused to simply reinstate the old language of the Missouri Compromise of 1820. The Republicans’ reactions assured secessionists that all hope of saving the Union was lost. By the time the debate was underway, South Carolina had already seceded. Sources: Daniel Crofts, Reluctant Confederates: Upper South Unionists in the Secessionist Crisis (Chapel Hill, 1989), 196-200. Thomas Purvis, A Dictionary of American History (New York, 1995), 97.