Schmitt David Schmitt Professor Claudia Skutar 546: (Meta 15SS

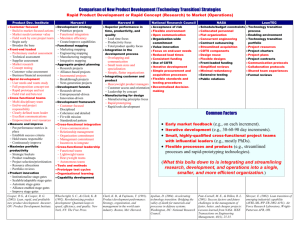

advertisement

Schmitt 1 David Schmitt Professor Claudia Skutar 546: (Meta 15SS) INTERMEDIATE COMP (015-016) February 10, 2015 General Undergraduate Business Degree Opposed to Specialty Undergraduate Business Degree Kristin Schelfhaudt and Victoria Crittenden co-authored the article “Specialist or Generalist: Views from Academia and Industry” in the Journal of Business Research. The article contained several excellent points regarding balancing the need of general business knowledge in the business education curriculum with also acquiring a “functional expertise” (Schelfhaudt and Crittenden 946). The data was obtained through interviews and questionnaires. Their methodology was sound and adequately documented, but a larger sampling may have provided more insight. The article was informative, but underwhelming in a definitive conclusion. The article relies on the term “cross-functional integration” (Schelfhaudt and Crittenden 946). Overall, the article developed a good argument toward the need of undergraduates to gain general business knowledge, while also obtaining specific business knowledge and skills that would benefit an employer. As a business major, I felt invested in the findings of the study. As I suspected, the article confirmed my thoughts that a balance between general business knowledge and a specific specialty is what employers are seeking. Therefore, cross-functional integration is important. Schelfhaudt graduated summa cum laude with a B.S. in Management, with a concentration in Operations and Technology Management, from Boston College. She was a Schmitt 2 member of the Carroll School of Management Honors Program. She also earned her J.D., cum laude, from Boston College Law School. On the other hand, Victoria Crittenden is a member of the marketing department faculty at Boston College, where she served as department chair for nine years and chair of the M.B.A. core faculty for three years. She has an M.B.A. from Harvard University. The credentials of Schelfhaudt and Crittenden’s are impressive and adds ethos. The survey and questionnaire provide most of the insights of the study. From the sited excerpts, the reliability and validity seems accurate and sound and I am sure they can be replicated. The surveys, which were directed at three different audiences, allowed me to view data about the value of my educational choice from a student perspective. I was also presented with the skill desires of future employers and the academic community’s goals. The credibility of the authors add to the overall integrity of the article and in how they interpreted the data. As mentioned previously, the article focused on information obtained from three sample sources. Perspective employers were given nine questions primarily regarding cross-functional coordination and the business expectations of general and specific business knowledge. Business professors were given a twelve question questionnaire that focused on the degree of integration between entry-level business courses and specific business courses in the academia realm. The final group consisted of junior and senior undergraduate students in the B.A. or B.S. business field. They were given fifteen questions which encompassed a broader scope than the two previous surveys. The focus was more on perceptions of what they thought basic knowledge and expertise entails. The data is the backbone of the piece and the analysis and conclusions are appropriately based on this data. I would have preferred a larger sampling of business consultants and academic professors. The sampling was small with five business professionals interviewed, 53 business professors, and 153 undergraduate students. However, the sampling Schmitt 3 was sufficient to gain some wisdom. A larger sampling may have included additional, insightful, individual responses. Schelfhaudt and Crittenden maintains that the analysis of the business professors and the business professionals took much more time than the student surveys. “Over fifty pages of transcripts were analyzed to identify general thematic links and patterns in the data” (Schelfhaudt and Crittenden 950). This data concluded that students should find a balance between general business knowledge and also seek courses or even another degree involving specific business specialties. While I did not find this conclusion surprising, I did gain a better understanding as to why. Finance majors with little general business knowledge will lack the broader picture of their role within the company. Companies view an employee’s limited focus as being detrimental to overall company goals. These employees may also take more time to adapt to the company culture. On the other hand, a business degree with no explicit business specialty is less appealing to the employer. Employees will experience a higher learning curve in the niche of the business where they are placed. Therefore, the conclusion was made that a mixture of general business knowledge and specific business knowledge is important. Schelfhaudt and Crittenden assert: Today’s employers want the best of both worlds. They are not satisfied with the myopic individual who views the operations of a business solely through the lens of individual functional areas. However, they are not content to abandon the crucial knowledge and expertise provided by specialists. Rather, employers are searching for the individual who has it all. (950) An important counter-argument was presented that time and money prohibits many students from pursuing the path of a double major. Furthermore, the study asserts that the MBA Schmitt 4 curricula has been revised to encompass more of a cross functional education. However, the effectiveness of the undergraduate curricula is questioned, “…concern has been expressed as to whether undergraduate business programs have been as adept at providing students with skills that will help them succeed in a progressive business environment” (Schelfhaudt and Crittenden 950). I found the consensus about the business professionals a little discouraging. The study concluded that the business world wants all the basic knowledge in place, plus an employee that has specific business expertise. I did not find it informative or surprising that potential employees want both, regardless of the time and cost to a student. Another interesting counterargument against stressing cross-functional integration was that outside influences can adversely it. The article mentioned that government regulations such as Sarbanes Oxley, that segregate job duties, inhibit the team work cross-functional idea. Although, I thought that the article was wellbalanced in presenting opposing arguments that cross-functional integration is important, I was disappointed that global influences were ignored. Outsourcing has had tremendous effects on the business environment. In particular, entry jobs in business have been affected by outsourcing and that has opened a whole other avenue of business strategy, ethics, and ethnocentric issues that complicate this concept. The group consisting of college faculty professors were quick to point out their courses and programs that contributed to cross-functional integration. Schelfhaudt and Crittenden maintains that the questions were altered from the business professional to accommodate the academia world of the business professors. However, I found some portions of both the professional business and academic responses to be self-serving. Each professor was able to site extensions to their business program that added to cross-functionality. This included field trips, international excursions, team competitions and options for additional research. When asked to Schmitt 5 evaluate the effectiveness of their business school program, they all gave their college above average ratings. I believe pathos was incorporated most with this group in the questionnaires, opposed to the more logos approach with the other two groups. Academic professors were asked to evaluate the effectiveness of their business programs and courses. Who is going to answer that they or their college are not doing their job? If college programs are truly in place for business cross-functional integration, then why is there dissatisfaction from the business world? I question whether business professionals are being too demanding in their requirements or if colleges are being too optimistic in the effectiveness of their degrees. Alternatively, the student questionnaire focused on whether undergraduate students understood cross-functional issues and if they felt their program was adequately preparing them for such. I would have preferred to evaluate responses from four-year B.A. and B.S. business graduates. How did they feel about their preparedness to meet the demands of the business job market? Students obviously have some choices as to the various degrees of functional and general knowledge in their undergraduate studies. “To quote an executive, “I prefer someone who has a specific functional excellence but has general management capabilities and a broad perspective. This is the person who says, ‘I can do other things, but I'm excellent at this.’” (Schelfhaudt and Crittenden 951). The business professionals acknowledged, however, that entry-level employees are rarely able to meet such standards. The business professionals were given the opportunity of conditional responses when asked about their preferences and when forced to choose between generalists and specialists in the hiring process. The responsibilities of the position is still the predominant factor. “Within the data set, consulting and accounting leaders were most likely to prefer the specialist over the generalist in an entry-level position” (Schelfhaudt and Crittenden 951). Student schedules are limited. The general plan is to develop both general business Schmitt 6 knowledge and specific functional skills within four years. In some cases, this is in addition to a liberal arts education. Therefore, a curriculum focused on cross-functional learning can force students to sacrifice expertise in a highly defined discipline, such as in accounting. Colleges can take years to find the right level of integration and develop a curriculum that achieves the tenuous balance between general and specific business knowledge. Restructuring an existing business curriculum is a huge commitment of time and resources, with results that are not immediate or easily measurable. Undergraduate students are the ones with the most to lose. They are competing with students with M.B.A.s, double majors, and those students who went beyond the degree requirements. The concluding quote of the article did not present a definitive solution in its summation. “You don't want to go for a corner solution. You don't want to think about a specialist or a generalist. That's the wrong answer. You want to develop a healthy tension between the two throughout a person's career (Schelfhaudt and Crittenden 953). The article convinced me that cross-functional integration is important. While I would have preferred additional insights from a larger sampling, I think the point was made that some education on a specific business function is highly desirable if you pursue a general business degree. Conversely, if you pursue a specific business degree, you want to include as many general business classes as possible. Regardless of some of the counter-arguments, I think this is the reality of the ever-changing business world. Business students need to be aware of this dynamic. The colleges that refine the curriculum to meet this demand will be the most successful. Not surprisingly, the business community will continue to hire the most qualified applicants. Challenging economic conditions and company philosophies will continue to push businesses to get the most leverage out of their employees’ skills. An employee with both general and specific business knowledge will be positioned to accomplish that company’s goals. Schmitt 7 REFERENCES Schelfhaudt, Kristin, Victoria L. Crittenden. “Specialist or Generalist: Views from Academia and Industry” Journal of Business Research 58.7 (2005): 946-954. Web. 23 January 2015.