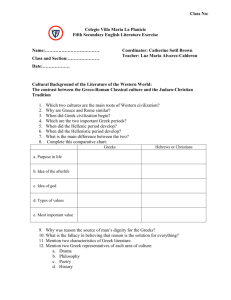

Tahoma - Teacher Barb

advertisement

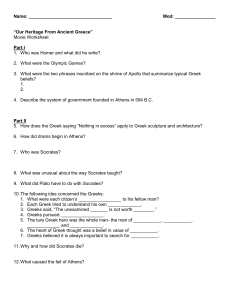

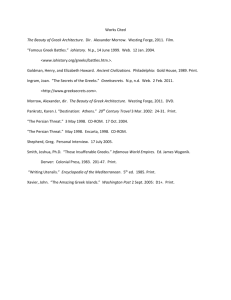

Overview 1: Beginnings through Ancient Greece *Bold words within the text indicate important notes to remember 1. Before the invention of writing, stories and songs were transmitted orally from generation to generation. Without written documents of this oral tradition, there was always the risk of its literature being irrevocably lost due to cataclysms such as foreign conquest or natural disaster. Writing was not invented for the purpose of preserving literature; the earliest written documents contain commercial, administrative, political, and legal information, and were created by the first "advanced" civilizations in an area that Westerners commonly call the Middle East. These ancient civilizations were agrarian, developing in the valleys of the Nile, Tigris, and Euphrates rivers. Cities began as centers for administration of irrigated fields, but they soon became centers for government, religion, and culture. The Egyptians built temples and pyramids in Thebes and Memphis; the Sumerians, Babylonians, and Assyrians build palaces and temples in Babylon and Ninevah. 2. The oldest writing was pictographic, meaning that the sign for an object was written to resemble the object itself; later, hieroglyphic and cuneiform scripts were invented to record more complicated information. The oldest extant texts date from 3300 to 2990 BCE and consist mostly of lists of foodstuffs, textiles, and cattle. Though such lists were well served by pictographs, by 2800 BC scribes began to make marks in a script that was later called cuneiform—the Latin cuneus means "a wedge"—to record more complicated information such as historical events. This form of writing survived more than two millennia. In Egypt, scribes developed a different form of writing. Named at a later date after the Greek words for "sacred" and "carving," hieroglyphs also developed in more cursive versions for faster writing. 3. Begun in 2700 BCE and written down about 2000 BCE, the first great heroic narrative of world literature, Gilgamesh, nearly vanished from memory when it was not translated from cuneiform languages into the new alphabets that replaced them. Gilgamesh was reintroduced to the world when a portion of it, Utnapishtim's Story of the Flood, upon which the biblical story of the flood is based, was accidentally discovered in 1872. Since then, tablets containing other parts of Gilgamesh have been found at sites throughout the Middle East in various cuneiform languages. Though the identity of its author and context are now lost, its stories, with their astonishing immediacy, appeal to modern readers. With this profound familiarity, there is also something infinitely strange and remote about Gilgamesh. The narrative is concerned chiefly with Gilgamesh's friendship with Enkidu, his quest for worldly renown and immortality, and his death. 4. Though the Hebrews left few visual arts (due in part to the prohibition against graven images) and little secular literature, they did leave a religious literature. Its texts were written down between the eighth and second centuries BC. The religion differs from other ancient religions insofar as it is founded on the idea of one god, who is infinitely just, omnipotent, and omniscient. The script that the Hebrews created consisted of twenty-two simple signs for consonantal sounds and survives, in modified form, today. Though the absence of written signs for vowels can confuse some readers, the consonantal script developed by the Hebrews ushered in a new form of writing that could be composed without special artistic skills and read without advanced training. Adopting the consonantal script of the Phoenicians, the Greeks added signs for vowels to form what is called the first real alphabet. 5. Unlike the rulers of the Tigris-Euphrates and Nile valleys, the Hebrews did not control an area of economic or military importance. They were not an imperial people, but began as pastoral tribes in Palestine who created Jerusalem as their capital. Their history includes foreign occupations by the Babylonians, Greeks, and Romans as well as exiles in Egypt and Babylon, and the Diaspora. After a period of expansion and prosperity under kings David and Solomon, the Hebrews were deported to Babylon in 586 BCE With their return to Palestine in 539 BCE, the Hebrews rebuilt the Temple and created the canonical version of the Pentateuch, the first five books of the Bible. By 300 BCE, the independent state of Israel was invaded and was eventually conquered by the Greeks and later absorbed into the Roman empire. After unsuccessful attempts to revolt against Roman rule under emperors Titus and Hadrian, the Hebrews became a people of the Diaspora. It was not until the twentieth century that Israel was reestablished as an independent state. 6. According to Hebrew religious attitudes, God created a perfect and harmonious order; physical and moral disorder is a consequence of Adam and Eve's disobedience. As the stories in the Bible expound, unlike polytheistic religions in which gods often battle among themselves for control over humankind, the sole resistance to the Hebrew God is humankind itself. The exercise of free will, which may be used for both good and evil, is in some mysterious way a manifestation of God's will. Hebrew teachers later carried on the story of the Fall and developed the concept of a God who is as merciful as He is just, who brings about the possibility of atonement and reconciliation. This concept is highlighted in the stories of Cain and Abel, Noah and the Flood, and the Tower of Babel, among others. The stories of the Bible teach lessons about humankind's proper relations to God, which themselves are a generational process that concentrates on the origins and development of the Hebrews as God's chosen people. 7. Though the origin of the Hellenes, or ancient Greeks, is unknown, their language clearly belongs to the Indo-European family. Named after the mythical king Minos, the Minoan civilization flourished on the island of Crete in the second millennium BCE In the same period, the Myceneans developed a wealthy and powerful civilization on mainland Greece. At some point in the last century of the millennium, the great palaces were destroyed by fire. With them, the arts, skills, and language of the Myceneans vanished for the next few centuries, a period called the "Dark Age" of Greece. Much of what we know about them is based on the body of oral poetry that became the raw material for Homer's epic poems, the Iliad and Odyssey. 8. By serving as a basis for education, the Iliad and Odyssey played a role in the development of Greek civilization that is equivalent to the role that the Torah had played in Palestine. The irreconcilable difference between the Greeks gods of Olympus and the Hebrew god led to a struggle from which only one survived. For those raised under monotheistic religions or cultures, the Greek gods and their relation to humanity may seem alien. Whereas the Hebrews blamed humanity for bringing disorder to God's harmoniously ordered universe, the Greeks conceived their gods as an expression of the disorder of the world and its uncontrollable forces. To the Greeks, morality is a human invention; and though Zeus is the most powerful of their gods, even he can be resisted by his fellow Olympians and must bow to the mysterious power of fate. 9. Though united by their common Hellenic heritage, Greek city-states differed in customs, political constitutions, and dialects. They were often rivals and fierce competitors, establishing colonies in the eighth and seventh centuries along the Mediterranean coast. The Greeks who established colonies in Asia adapted their language to the Phoenician writing system, adding signs for vowels to change it from a consonantal to an alphabetic system. First used for commercial documents, writing was later applied to treaties, political decrees, and, later, literature. 10. Inspired by their defeat of the Persian invaders, Athens and Sparta emerged as the two most prominent city-states of the fifth century BCE With the elimination of their common enemy; however, the two cities became enemies, culminating in the Peloponnesian war, which left Athens defeated. Before its defeat to Sparta, Athens developed democratic institutions to maintain the delicate balance between the freedom of the individual and the demands of the state. By the time of Sophocles, Athens had become an empire, establishing a league of subject cities, which it taxed and coerced. 11. Professional teachers, called Sophists, educated affluent male citizens of Athens in the techniques of public speaking and in subjects such as government, ethics, literary criticism, and astronomy. The secular and humanist spirit of Athenian culture is best expressed in the words of the Sophist Protagoras: "Man is the measure of all things." Unlike the Sophists, Socrates proposed a method of teaching that was dialectic rather than didactic; his means of approaching "truth" through questions and answers revolutionized Greek philosophy. Socrates exposed illogicality in old beliefs but did not provide new beliefs. His ethics rested on an intellectual basis. Due to his insistence that it is the duty of each individual to think through to the "truth," resentment against Socrates built, culminating in a death for impiety. In the next century, Athens became a center for schools of philosophy based on his ideas, especially as espoused by Plato and Aristotle. Founder of the Academy in 385 BCE, Plato's literary and philosophical contributions often explored ethical and political problems of his time featuring his teacher Socrates as speaker. The first systematic work of Western literary criticism, the Poetics, was written by Aristotle, a member of Plato's Academy. 12. Except for his name, we know nothing about the poet Homer, and there is no trace of his identity in the poem. The basis for Homer's Iliad and Odyssey was an immense poetic reserve created by generations of singers who lived before him. Homer made use of an intricate system of metrical formulas, a repertoire of standard scenes, and a known outline of the story. Unlike most oral literature, the poetic organization of the two works suggests they owe their present form to the hand of one poet. 13. Focused around the events that transpired in a few weeks of the ten-year Trojan War, the Iliad tells the story of the Achaeans and Trojans in war. Both genders—the men who do battle and the women who depend on them—are affected in this tale of war. Starkly unsentimental, Homer's tale suggests that human beings must implicitly deal with both destructive and creative impulses. The Odyssey deals with the peace that ensued and places emphases on the lives of the surviving heroes of the war. It tells the story of Odysseus on a quest to return to his homeland, Ithaca, and be reunited with his son and wife. Along the way, he has many adventures and must rely on his intellect, wit, and strength to extricate himself from perilous situations. Neither the Iliad nor the Odyssey offers easy answers; questions about the nature of aggression and violence are left unanswered, and questions about human suffering and the waste generated by war are left unresolved. 14. Though Sappho's lyric poems give us vivid evocation of the joys and sorrows of love, it is the drama that emerged more than a century later that is most closely associated with classical Greek literature. Greek comedy and tragedy developed out of choral performances in celebration of Dionysus, the god of wine and mystic ecstasy. Thespis was probably the first to add a masked actor, who engages in dialogue with the chorus, to these performances; later Aeschylus added a second actor, creating the possibility for conflict and establishing the prototype for drama as we know it. The seven plays of Aeschylus are the earliest documents in the history of Western theater. While Aeschylus' plays reflect Athens's heroic period, those by his younger contemporary Sophocles, especially Oedipus the King, reflect a culture that was reevaluating critically its accepted standards and traditions. Even more so, Euripides's Medea is an ironic expression of Athenian disillusion. The work of the only surviving comic poet of the fifth century, Aristophanes, combines poetry, obscenity, farce, and wit to satirize institutions and personalities of his time. Though parodic in tone, the work often carries serious undertones, thus adding to the rich diversity of writings from the ancient Greek world.