Busy guide to getting your conference paper accepted

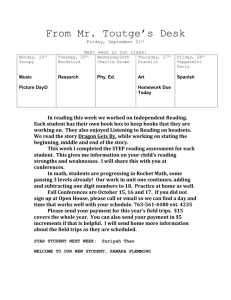

advertisement

Busy teacher educator guide to getting your conference paper accepted/ writing an abstract for an education conference Sue Bloxham and Alison Jackson, University of Cumbria/ESCalate Introduction Many people are involved in really interesting and valuable research and development in teacher education but struggle to get their work accepted for conferences. Most conferences blind review conference submissions so you don’t need to be a big name or a long-standing researcher to have a fair chance. But you do need to write a good abstract. This Busy Teacher Educators’ guide has been developed out of workshops we have run for several years on writing abstracts for conferences. We have had a virtually 100% success rate amongst the workshop delegates in getting their submissions accepted so we are making the information available for everyone in this guide. What is an abstract? An abstract is a summary of an academic paper or longer piece of work which sets out in a brief, cogent way an outline of what the reader can expect from the full work. Writing an abstract is a professional skill which requires time, care and commitment to perfect. Which conferences? The discussion in this document is designed to be particularly relevant to teacher educators in Initial Teacher Education. Possible conferences are: The Education Subject Centre conference (ESCalate) www.escalate.ac.uk/ite The British Education Research Association conference (BERA) www.bera.ac.uk The Higher Education Academy conference (HEA) www.heacademy.ac.uk The Improving Student Learning conference (ISL) http://www.brookes.ac.uk/services/ocsld/isl/isl2008/index.html The Society for Research in Higher Education conference (SRHE) http://www.srhe.ac.uk/conference2008/venue.asp Your own university’s teaching & learning conferences and many other international education conferences too numerous to mention. It is wise to select a conference that matches your interests and experience as a researcher; for example, ESCalate particularly welcomes submissions from practitioner researchers working in teacher education; BERA has a broader remit as its aim is to sustain and promote a vital research culture in education, it does, however, have a popular SIG (Special Interest Group) on Teacher Education and Development and other SIGs which might be relevant to you http://www.bera.ac.uk/sigs/siglist.php . Papers/ symposia/ roundtables/ posters? Look carefully to see which of the different conference formats most suit your work. Posters are generally easier to get accepted and good for work in progress. In general, it is important to read carefully what each conference is looking for in each category because they can be very different. For example, some have a category called ‘research papers’ where you are expected to only submit work which is extending theory or methodology. Others (e.g. ESCalate) use ‘papers’ to define a wide range of research and scholarly activity which you may have been engaged in which will impact on the practice of the community it serves. Engagement with roundtables can be difficult, not least because of the differences in definition of the term between institutions. Normally you are not expected to present for more than a few minutes (often in a very noisy environment). Instead, the main focus is on leading a discussion on a topic which you want to share with colleagues. Linking to conference themes Conferences use their themes rigorously in their review process for selecting which abstracts to accept. If you do not make sure your paper links clearly to a conference theme, you are likely to get it rejected however good it is. This may need a bit of creative thinking but is essential. Getting noticed Your abstract serves two purposes; one is to get the paper accepted; the second and equally important purpose is to attract delegates to your session. So remember that reviewers and conference delegates are busy like you and your abstract needs to grab their attention. Think about what is most likely to do that and make the title and first sentence eye-catching. Consider a striking title with a ‘catchy’ first part, joined by a colon (if appropriate) to a sub section which gives an idea of the main topic, for example: Understanding the rules of the game: developing students’ understanding of assessment criteria Wicked Wikis: using a wiki to transmit pre-course information to ITE students and to develop on course collaborative working Teachers; the reluctant professionals? A call for an individual response It is also worth making clear at the beginning of your abstract how your work links to important current debates, issues, or policies – topics that the reviewers and the delegates are likely to be interested in. Structure Conference submission may be either in the form of a number of boxes with specific questions to be answered or you may be asked you to summarise everything in one abstract. You will be condensing weeks, months, even years of work into an abstract to give a presentation which may only last as little as 20 minutes, so be cautious, do not try to push everything in at the expense of clarity and style. Be selective, be sensible, what can you say that will interest the reader so much that he or she will want to follow up what you said either by attending your presentation or by reading your paper? (See below for ‘Reducing your wordage’) Here is one example of a suggested abstract format, but beware, it may not work for your topic or your chosen conference. The sections can be shorter or longer depending on how many words you are allocated. Introductory sentence saying why the topic is an important issue (link to conference themes) Brief summary of what other research to date has shown about the topic; key concepts and findings. Leading to how this paper builds on that existing research Aim of research Summary of methodology / data collection methods Early findings if available Aspects to be discussed at the conference, e.g. impact on practice, theoretical developments, link this to conference theme If you have difficulty getting going, many colleagues find Brown’s 8 questions a useful tool for getting started. Again, do not assume that by answering these questions, you have ‘cracked it’, but you will probably be a lot nearer knowing what it is to you are trying to crack! Brown’s Eight Questions This describes a tool that writers find useful for outlining a piece of work. Some find it helps them to write the summary or abstract of a paper. The shaping of ideas, information and intuition into a coherent whole can be initiated by Brown’s eight questions. In the course of this short article Brown gives eight questions for summarising a piece of research. They can be extremely helpful in focusing the writing. Whether you find them useful is up to you. They are deceptively simple, the hard part is thinking and persisting through several drafts. They can be adapted to your own questions if you wish for later work. This approach can be used not only to reveal the central argument, but also to discover it. They are presented with their original word limits to show the percentage suggested for each part – they come to approximately 300 words. 1. 2. 3. 4. Who are the intended readers? (list 3-5 names) What did you do? (50 words) Why did you do it? (50 words) What happened? (50 words) 5. 6. 7. 8. What do the results mean in theory? (50 words) What do the results mean in practice? (50 words) What is the key benefit for the reader? (25 words0 What remains unresolved? (No word limit) Sources: Brown, R. (1994/5) Write first time, Literati Newsline, Special issue, 1-8 Murray, R. (2002) How to write a thesis, Buckingham, Open University Press. Theoretical framework Conferences are places where people share new developments in their fields before work is further developed for publication. Whilst some may be interested in just hearing about practice, most conferences will expect your paper to be academically rigorous, showing that you have engaged with the scholarship in that field of study. So your abstract needs to briefly demonstrate that your work has taken account of previous research. It should also make clear any concepts that you are using, e.g. ‘reflective practitioner’, ‘neo-liberalist education policy’, ‘Foucaultian concepts’ etc. Your findings should also be linked to your theoretical framework; do they substantiate, add to or contradict existing ideas and empirical evidence? References It is inappropriate to use lots of references; they take up too many words and are not useful in a short abstract. However, you may wish to cite a few publications to illustrate the body of knowledge from which you are drawing. If there is no direct instruction about how to reference in the abstract, you can either list them at the bottom or, where the word count is short, state: ‘full references will be supplied with conference paper’. Some instructions indicate that references are not part of the word count for the abstract. Reducing your wordage If you find that you just have too much to say (a common problem) here are a few hints to reduce the wordage – do not think no one will notice if your abstract is too long, some electronic versions do not allow you to overshoot the mark and for others, the reviewer will certainly notice and not be impressed! Take out words that don’t add any meaning Change the sentence order, using active rather than passive verbs to make the text clearer and shorter Are you using long expressions when a single term will do? For example ‘It is really important to notice how significant the findings are and I will now list these’ is better as ‘Significant findings are:’ Think - what is they key point in a sentence or paragraph? Try rewriting to just include that point. Language and acronyms Do not assume that your reader has any specialist knowledge of your research topic or specialist acronyms. You need to define unfamiliar terms and avoid specialist jargon in order to improve the understanding of your audience. Remember – you know far more about your topic than anyone else. Can you read your abstract out loud with ease? This is a really good test of readability. If it sounds wrong, it probably is. Use a thesaurus and a dictionary to improve your style and ensure you say what you think you mean! Problems with curriculum subject specific papers If your paper is restricted in its appeal to a wide audience because it is very specialised, check the conference you are addressing. This may be acceptable, but in many cases would not be. Knowledge is transferable and what you have to say may very well have resonance in a number of forums. Work to link your abstract to the area required in the conference. Never ‘throw out’ the same abstract to a number of different conferences in the hope that someone will like it. The reviewers will notice it is irrelevant to their conference and reject it and you may well miss them all! Length If the abstract limit is fairly short (200-500 words), you should try to use them all. If the word limit is longer, you may find you can write a good summary in fewer words. However, if you use considerably less than the word limit, you may disadvantage yourself because others will have put in more detail. It is to be supposed that the word limit has been chosen with care and that the organisers of the conference do not expect you to deviate wildly from what they have prescribed. Templates In the same way, if you are given a template, there will be a reason; dealing with a large number of submissions needs to be streamlined to be manageable. Make sure you use the template, answer all the questions and fill in all the required sections. Work with someone/ talk to someone There is nothing as valuable as getting someone else to read your abstract. That person does not have to know what your topic is about, in fact it is often better that they do not as then you will have had to be clear and concise in order for them to follow your meaning. Where to look for more advice Many university staff development centres have materials that you could use. Go to conferences and look at previously accepted abstracts Attend Abstract Writing sessions if possible