Memetic Emergence of Public Opinion

advertisement

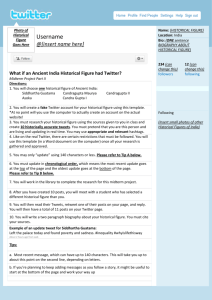

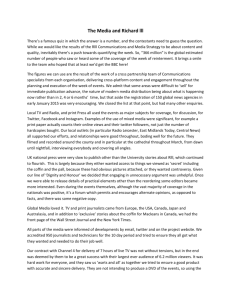

WAPOR 64th Annual Conference Public Opinion and the Internet Short Research Paper Memetic Emergence of Public Opinion Marco Toledo Bastos (University of São Paulo / University of Frankfurt) 1. Paper Outline The aim of this paper is to discuss the propagation of opinions expressed on the Internet in view of a historical development of public opinion. In order to address that, the paper examines the debate concerning the public opinion by the theories of Walter Lippmann (1961), Niklas Luhmann (2000), Jürgen Habermas (1987) and Dirk Baecker (2005). The relationship between media and the public opinion is defined by the historical emergence of forms of coding between communication agents, previously comprising of senders and receivers (peer to peer communication), broadcasting (mass communication) and networks of nodes (digital communication). The dynamics of public opinion in digital environments is depicted as a form shaped by a network of nodes, so that we suggest the memeotic diagram to model the distribution of messages and opinions in digital networks. The paper offers a synthesis of the literature on public opinion and introduces the methods and the results from a quantitative investigation into the viral propagation of messages in the Twitter network. 2. Public Opinion The concept of public opinion was established as an empirical aggregate of individual opinions, ideas and agendas within the adult population. The concept has been used to address the organic complex of opinions that different people grasp together, not individually, and how the sum of opinions affect society. The concept itself gained acceptance in the eighteenth century with the rise of the public sphere centered upon the Enlightenment in Europe. The English term derived from the French l’opinion publique, coined in 1588 by Michel de Montaigne (Lemert 1981). Because of this conceptual dependency, the development of the concept of public opinion is mirrored on the history of the modern era and the process of urbanization. According to Fred Cutler (1999), it was Jeremy Bentham who first presented a solid theory about the public opinion. The British philosopher and social reformer claimed that public opinion could pressure lawmakers and assure that rules were to be made for the best of everyone. For Luhmann (1990) public opinion is a paradox that pictures the invisible power of the visible. As a technological outcome from writing—which creates the public and afterwards the public opinion—it would not be related to the opinion of individuals, to a certain social judgment or to a general agreement in relation to a certain topic. Instead, it would be a network of communications that no one is required to take part of. This network would be significantly entropic and any action towards public opinion would require a great deal of labor. In accordance to his concept of communication, public opinion does not convey any transmission of information, but rather disseminates information within a system. The public opinion would be a medium by which forms are created and dissolved through continuous communication. It would be a bottom-up social reality based on the very reproduction of communication (Maresch 1999). Luhmann (1990: 174) portrays the public opinion by way of the binary medium/form polarization, where media are the weak gathering of overabundant elements and forms represent the provisory selection of such overabundant elements in a strong cluster. Public opinion is therefore the temporary gathering of consciousness, by means of a structural coupling in view of a specific horizon of meaning. The lack of permanent properties makes public opinion a somewhat imaginary reference to which consciousness refers, at the same time the consciousness are not permeable to the public opinion. Mass media shape the public opinion but do not transfer contents to it. As a compound of auto-organized atomistic opinions, public opinion is produced by temporal and quantitative forms as an autonomous and differentiated and self-created reality. This autonomous reality allows an observer to observe the medium while all the observers are mirrored on it as public opinion (Luhmann 1990: 181). 3. #FreeVenezuela Network The data collected for this paper refers to a story very similar to the role Twitter played during the 2009-2010 Iranian election and the recent political events in Tunisia and Egypt. The data was collected from January 22, 2010 to May 2, 2010 concerning to the hashtag #FreeVenezuela, the tag used to categorize posts related to the socioeconomic situation in Venezuela. This particular hashtag attracted a great deal of protesters reaching the third position in Twitter’s trending topics at the beginning of February 2010. It was on January 22, 2010 that the first tweet with the hashtag #FreeVenezuela was posted on Twitter as a result of a protest against the banning of cable station Radio Caracas Television (RCTV) and five other stations by Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez. The context of the Venezuelan uprising with the hashtag #FreeVenezuela relates to a moment of economic crisis, political uncertainty and threats against freedom of speech in Venezuela. The data collected shows an increasing amount of tweets collected around the aforementioned hashtag as protests reached the streets and news of the protests made its way on to mainstream media and social networks Twitter, Facebook and Youtube. Based on this hypothesis, our paper sheds some light on the powerful role that social networking websites are playing in the organization of social and political consent and dissent. 4. Twitter Memeoids The theoretical framework focuses on the hashtag memeotic emergence in Twitter using a set of theories and methodologies to mine and analyze social media data. The word memeotic depicts a pattern of information replication that contrasts to the idea of viral emergence of messages and information. While viral refers to a reproduction pattern in which interaction and viral replication are achieved against host defenses, the memeotic replication refers to a pattern different from virus mechanics because it achieves a state of stable symbiosis with the host (Twitter network). Memeotic revolves around the work of Richard Dawkins (2006), who used the term meme to describe a unit of human cultural transmission analogous to the gene, arguing that replication also happens in culture though in a different sense. For Dawkins, a meme is a unit of information but also a pattern that can influence its surroundings––that is, it has causal agency––and can propagate. We described Twitter as an evolutionary system constituted by two main agents. Individual tweets are named memes (M) that are reproduced through retweeting and are subject to mutation (e. g. by changing parts of the message or including markup conventions like hashtags and links). Memoids (Mmo) are entities that reproduce inside tweets and that improve tweets replicability rates, but are also replicating units themselves (e. g. hashtags and links). A Mmo is not restricted to unique tweets lineages; in fact, it will frequently infect various memes simultaneously. Memes have the following state variables: length, idiom, hashtag richness, http links richness, RT count, AT count, and user (the person who published the tweet). Memoids have the following state variables: class (hashtag or http link), length and subject. Last, the Followers Networks (FN) are virtual communities that provide an environment where users can receive, produce, and replicate tweets. The results of these tweets provide a further environment in which M and Mmo are reproduced. @ Network RT Network #FreeVenezuela Friends/Followers Network M / Mmo variables @ edges indegree @ edges outdegree FF edges indegree FF edges outdegree Followers Count Friends Count Date of account creation Statuses count #FreeVenezuela RT outdegree correlation 49,90% 33,67% 7,51% 8,54% 6,92% 4,98% 0,93% 8,55% NUMBER OF TWEETS PER USER 73,93% 5. Conclusion The paper takes into consideration that the emergence of political hashtags in Twitters network are the direct outcome of economic crisis, political uncertainty and threats against freedom of speech. In the conclusion, the paper argues that Twitter trending topics form a digital public opinion that challenges the “rich-get-richer” dynamics described by Barabási and Albert (1999) as a common feature in systems such as genetic networks and the World Wide Web. Even though the propagation of opinion in Twitter networks follows a scale free network, there is no substantial evidence of any power-law distribution. This is mainly because unlike systems based on power-law distribution, the propagation of opinions in Twitter networks does not rely on scale invariance, but rather on effective scale variation—that is, on memeotic variance. In the final conclusion, the paper presents the “clickers” hypothesis, which sheds light on the very powerful role of social networking websites in the organization of social and political consent or dissent in today’s world. 6. References Cutler, Fred (1999), 'Jeremy Bentham and the Public Opinion Tribunal', The Public Opinion Quarterly, 63 (3), 321-46. Baecker, D. (2005). Form und Formen der Kommunikation. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. Barabási, A.-L., & Albert, R. (1999). Emergence of Scaling in Random Networks. Science, 286(5439), 509-512. Dawkins, R. (2006). The selfish gene (30th anniversary ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Habermas, J. (1987). The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity. Cambridge: MIT Press. Lemert, James B. (1981), Does mass communication change public opinion after all? : a new approach to effects analysis (Chicago: Nelson-Hall) x, 253 p. Lewin, K. (1947). Frontiers in Group Dynamics. Human Relations, 1(2). Lippmann, W. (1961). Public opinion. New York,: Macmillan. Luhmann, Niklas (1990), Soziologische Aufklärung 5: Konstruktivistische Perspektiven (5; Opladen: Westdt. Verl.). Luhmann, N. (2000). The Reality of the Mass Media. Stanford: Stanford University Press. Maresch, Rudolf (ed.), (1999), Kommunikation, Medien, Macht (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp) 450. White, D. M. (1964). People, Society and Mass Communications. London: CollierMacmillan. 7. Authors Marco Toledo Bastos is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Center for Philosophical Studies of Communication from the University of São Paulo and a researcher of the Research Network for Media Anthropology (FAMe - JWG University of Frankfurt). Rafael Luis Galdini Raimundo, Rodrigo Travitzki de Oliveira and Paulo Guimarães Júnior have contributed to this research. 8. Contact POSTAL ADDRESS BRAZIL POSTAL ADDRESS GERMANY Avenida Caxingui 191, Apto 124. Rothlintstr 92 - Frankfurt am Main CEP 05579-000, Butantã PLZ 60389 São Paulo – SP. BRASIL GERMANY TELEPHONES BRAZIL TELEPHONES GERMANY (+55 11) 7102-4756 (work) (+49) 15158768326 (mobile) (+55 11) 3721-5034 (home) EMAIL ADDRESS EMAIL ADDRESS opus@usp.br herrcafe@gmail.com