Analyzing Argument

advertisement

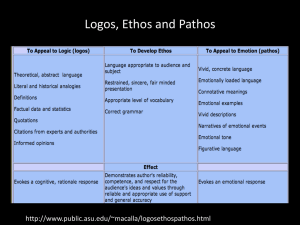

Analyzing Argument Aristotle hoped than mankind would embrace the logic of the syllogism and the enthymeme for making arguments. While he recognized the need for, and importance of, emotional appeals, he claimed that the affairs of mankind should be handled through logic. You will recognize the syllogism as the old "fluffy is a mammal" argument. It goes like this: All cats are mammals. Fluffy is a cat. Therefore, fluffy is a mammal. The enthymeme is the rhetorical syllogism, in which part of the logical sequence is left unstated. For example: Some politicians are corrupt. Therefore, Senator Jones could be corrupt. Humans are passionate creatures whose hearts and minds are moved with appeals to emotion (pathos), character (ethos), as well as logic (logos). The rhetorician must decide the proper balance of these appeals in the presentation of any argument. Forms of Argument 1. Induction: Argument by induction builds from evidence and observation to a final conclusion. Most people recognize induction as the basis for scientific method. Simple induction moves from "reasons" and examples to conclusion and does not require scientific observation or eyewitness reports. 2. Deduction: Argument by deduction builds from accepted truths to specific conclusions. The syllogism and enthymeme are examples of deductive arguments. We may also structure deductive arguments based on cultural or social truths leading to specific conclusions. 3. Narrative: Stories and anecdotes should not be considered innocent moments of entertainment in political communication. Narrative argues partly by denying its ability to persuade. Remember the powerful use Ronald Reagan made of anecdotes. He perfected the form for the modern presidency, and every president since has followed his lead. Aristotle’s Artistic Proofs How do arguments persuade? Aristotle said that rhetors persuade by effective use of "proofs" or "appeals." He divided proofs into two classes: 1) the inartistic proofs that one simply uses for inductive arguments (e.g. statistics), and 2) the artistic proofs that one must create. 1.) Logos: appeals to reason Such an appeal attempts to persuade by means of an argument “suitable to the case in question,” according to Aristotle. Appeals to logos most often use the syllogism and enthymeme. You may recognize the syllogism as the formal method of deductive reasoning (see above). The enthymeme is a truncated syllogism, also referred to as the rhetorical syllogism, in which one or more minor premises are left unstated. You may recognize the enthymeme as assertions followed by reasons. We rarely find syllogisms in their pure form in civic discourse. Instead, we find statements and reasons that are incomplete and are therefore enthymemes. For example: “We do not have enough money to pay for improvements to our railroads. And without improvements, this transportation system will falter and thus hinder our economy. Therefore, we should raise taxes to pay for better railroads.” 2.) Pathos: appeals to the emotions of the audience Such an appeal attempts to persuade by stirring the emotions of the audience and attempts to create any number of emotions, including: fear, sadness, contentment, joy, pride. Pathos does not concern the veracity of the argument, only its appeal. For example: Bob Dole wants to hurt the elderly by cutting Medicare. 3.) Ethos: appeals exerted by the character of the writer/speaker Such an appeal attempts to persuade by calling attention to the writer’s/speaker’s character. It says in effect: “I’m a great guy so you should believe what I’m telling you.” Ethos does not concern the veracity of the argument, only its appeal. For example: I am a husband, a father, and a taxpayer. I’ve served faithfully for 20 years on the school board. I deserve your vote for city council. http://www.rhetorica.net/argument.htm Whenever you read an argument you must ask yourself, "is this persuasive? And if so, to whom?" There are several ways to appeal to an audience. Among them are appealing to logos, ethos and pathos. These appeals are prevalent in almost all arguments. To Appeal to Logic (logos) To Develop Ethos -Theoretical, abstract language -Denotative meanings/reasons -Literal and historical analogies -Definitions -Factual data and statistics -Quotations -Citations from experts and authorities -Informed opinions -Language appropriate to audience and subject -Restrained, sincere, fair minded presentation -Appropriate level of vocabulary -Correct grammar Evokes a cognitive, rationale response Demonstrates author's reliability, competence, and respect for the audience's ideas and values through reliable and appropriate use of support and general accuracy To Appeal to Emotion (pathos) -Vivid, concrete language -Emotionally loaded language -Connotative meanings -Emotional examples -Vivid descriptions -Narratives of emotional events -Emotional tone -Figurative language Effect Evokes an emotional response Logos: The Greek word logos is the basis for the English word logic. Logos is a broader idea than formal logic--the highly sybolic and mathematical logic that you might study in a philosophy course. Logos refers to any attempt to appeal to the intellect, the general meaning of "logical argument." Everyday arguments rely heavily on ethos and pathos, but academic arguments rely more on logos. Yes, these arguments will call upon the writers' credibility and try to touch the audience's emotions, but there will more often than not be logical chains of reasoning supporting all claims. Ethos: Ethos is related to the English word ethics and refers to the trustworthiness of the speaker/writer. Ethos is an effective persuasive strategy because when we believe that the speaker does not intend to do us harm, we are more willing to listen to what s/he has to say. For example, when a trusted doctor gives you advice, you may not understand all of the medical reasoning behind the advice, but you nonetheless follow the directions because you believe that the doctor knows what s/he is talking about. Likewise, when a judge comments on legal precedent audiences tend to listen because it is the job of a judge to know the nature of past legal cases. Pathos: Pathos is related to the words pathetic, sympathy and empathy. Whenever you accept an claim based on how it makes you feel without fully analyzing the rationale behind the claim, you are acting on pathos. They may be any emotions: love, fear, patriotism, guilt, hate or joy. A majority of arguments in the popular press are heavily dependent on pathetic appeals. The more people react without full consideration for the WHY, the more effective an argument can be. Although the pathetic appeal can be manipulative, it is the cornerstone of moving people to action. Many arguments are able to persuade people logically, but the apathetic audience may not follow through on the call to action. Appeals to pathos touch a nerve and compel people to not only listen, but to also take the next step and act in the world. Examples of Logos, Ethos and Pathos Logos Let us begin with a simple proposition: What democracy requires is public debate, not information. Of course it needs information too, but the kind of information it needs can be generated only by vigorous popular debate. We do not know what we need to know until we ask the right questions, and we can identify the right questions only by subjecting our ideas about the world to the test of public controversy. Information, usually seen as the precondition of debate, is beter understood as its by product. When we get into arguments that focus and fully engage our attention, we become avid seekers of relevant information. Otherwise, we take in information passively--if we take it in at all. Christopher Lasch, "The Lost Art of Political Argument" Ethos My Dear Fellow Clergymen: While confined here in Birmingham city jail, I came across your recent statement calling my present activities "unwise and untimely."...Since I feel that you are men of genuine good will and that your criticisms are sincerely set forth, I want to try to answer your statement in what I hope will be patient and reasonable in terms. I think I should indicate why I am here in Birmingham, since you have been influenced by the view which argues against "outsiders coming in."...I, along with several members of my staff, am here because I was invited here. I am here because I have organizational ties here. But more basically, I am in Birmingham because injustice is here. Just as the prophets of the eighth century B.C. left their villages and carried their "thus saith the Lord" far beyond the boundaries of their home towns, and just as the Apostle Paul left his village of Tarsus and carried the gospel of Jesus Christ to the far corners of the Greco-Roman world, so am I compelled to carry the gospel of freedom beyond my own home town. Like Paul, I must constantly respond to the Macedonian call for aid. Martin Luther King, Jr. "Letter from Birmingham Jail" Pathos For me, commentary on war zones at home and abroad begins and ends with personal reflections. A few years ago, while watching the news in Chicago, a local news story made a personal connection with me. The report concerned a teenager who had been shot because he had angered a group of his male peers. This act of violence caused me to recapture a memory from my own adolescence because of an instructive parallel in my own life with this boy who had been shot. When I was a teenager some thirty-five years ago in the New York metropolitan area, I wrote a regular column for my high school newspaper. One week, I wrote a column in which I made fun of the fraternities in my high school. As a result, I elicited the anger of some of the most aggressive teenagers in my high school. A couple of nights later, a car pulled up in front of my house, and the angry teenagers in the car dumped garbage on the lawn of my house as an act of revenge and intimidation. James Garbarino "Children in a Violent World: A Metaphysical Perspective Notes on Ethos, Pathos, and Logos: the three pillars of persuasion The Greek philosopher Aristotle identified the three available modes of persuasion (or "appeals") as being Ethos, Pathos, and Logos. I believe this way of thinking remains valuable for writers today. This lecture will review these three principles in general, encouraging you to shape your arguments with these ideas in mind. Ethos--This is ethical argument based on the character of the speaker. In other words, the appeal of ethos is to say, "I am a believable person, therefore believe me." Any elements of an essay that reveal the author as intelligent, caring, and knowledgeable about the topic will help persuade a reader that the argument is valid. A good example of ethos in argument is advertising that uses celebrity endorsements of products as their main pitch. In writing, strong appeal to ethos is created in a number of ways. Correctness and clear writing convey the intelligence of the author. Use of research and information shows the author's knowledge of the subject. What we call "writer's voice", which simply means the person and personality we hear while reading, is also a large part of this. Excessive anger may turn a reader off to the author, and so to the thesis, but a cold, dispassionate voice may do the same. Achieving a strong, wellbalanced and attractive authorial voice is an important part of creating persuasive arguments. Think of Martin Luther King's speeches in this light. The quality of his character as revealed in his words is a strong part of his persuasive appeal. That's ethos at work. However, ethos cannot be the only basis of persuasion in an effective argument. After all, even the best person could be wrong about a particular issue. A good argument will always be based in strong logical reasoning (logos), supported by ethos, and by emotional appeal as well (pathos). Pathos-- Pathos is the use of emotion to persuade in an argument. Emotions are powerful parts of our mental lives, and any argument that doesn't engage the emotions of its audience will seem incomplete. Emotions are conveyed a number of ways in essays. The two most significant ways to engage your readers' emotions are by using specific, vividly described examples, and by making your word choices with an awareness of the emotional connotations of words. Examples will activate emotions in a way that information will not. Consider your own reaction to two possible openings to an essay on AIDS. One way to start might begin with facts. "Last year, 20 thousand people lost their lives to AIDS." Another option would be to begin with an emotional example: "The young woman's emaciated face shows the ravages of AIDS. Though only 28, her thin, wrinkled skin looks like that of an elderly woman." While neither approach is necessarily better in a given essay, the strongest arguments always contain some emotional component, some use of Pathos to move the audience. Listen to a good political speech if you want more examples. Pathos is also conveyed via specific words choices. Words that mean the same thing in a literal sense often carry very different emotional connotations, and choosing between them is a large part of the art of argument. For example, if you look in a dictionary, you'll see that the word "administration" (as in "the Bush administration") has almost an identical definition with the word "regime". Check if you don't believe me. However, your reaction to the phrase "the Bush regime" will show you quickly how different the emotional meanings of the words are. Control of pathos in your essay means careful choices about the emotional valence of the words you choose. Logos-- Ethos and pathos, however, are both incomplete (though often effective) modes of persuasion. Because, finally, neither strong ethos nor powerful pathos shows that the argument is correct. What the Greeks called Logos, what we call logical reasoning, is the aspect of argument that must be the foundation for the essay. Logos means providing factually accurate and logically meaningful reasons in support of your positions. Logos means conclusions that follow from accurate assumptions and factual information. If ethos and pathos are ways of moving an audience to believe an argument, logos is the argument itself, the progression of ideas that leads to your conclusion. This lecture can't begin to engage in the many factors that make logical argument valid and effective. But I'll mention a few general principles here, that I will expand on in later lectures on syllogisms and on logical fallacies. Logical argument is rooted in the relationships between ideas, and the natural tendency we have to derive general principles from specific experiences. Strong arguments offer specific reasons for more general claims. The principle is, SUPPORT YOUR CLAIMS. When you claim that something is true, let your readers know why or how you know it is true. Strong logic also makes accurate claims about cause and effect relationships, and provides careful definitions of important terms and ideas. And good logical arguments tend to give lots of examples. In summary, the strongest essays make use of all three modes of persuasion, ethos, pathos, and logos. A good essay presents its author as a caring, intelligent, and well-informed person, someone to be believed. (ethos) Strong essays also move the emotions of their readers, using specific human examples and carefully chosen language to engage their readers' feelings. (pathos) But most importantly, good arguments develop a careful structure of thought based in valid logic and real-life experience. The best arguments, of course, are those that are true. Your job as a writer is to make that truth obvious and undeniable to your audience. https://teach.lanecc.edu/kenz/wrt122/lecturehall/arg.epl.html