Course Announcements - Athabasca University

advertisement

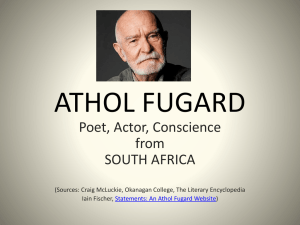

Course Announcement English 304 A History of Drama: Part II: Modernist Theatre Please note the following amendment to the Student Manual Student Manual Course Materials The course anthology, The Harcourt Brace Anthology of Drama, 3rd ed. is out of print and has been replaced with two texts: Worthen, W. B. ed. The Wadsworth Anthology of Drama. 5th ed. Boston: Thomson Wadsworth, 2007. Wertenbaker, Timberlake. Our Country’s Good. Woodstock, IL: Dramatic Publishing, 1998. Page references to the course textbooks in the Student Manual and Study Guide will not apply to the new anthology and play text. Please use the Contents and Indexes of the texts to find the assigned readings and plays. However, most of the assigned plays and readings remain the same. There are two exceptions, both in the Study Guide: Act III. 1. The play by Athol Fugard has been changed to “Master Harold” … and the boys (p. 1436, The Wadsworth Anthology of Drama, 5th ed.). 2. No Sugar by Jack Davis has been omitted. #543262 November 20, 2006 Assessment of Students’ Work Please note the following amendment to the Student Manual, page 6. In addition to the requirements stated, students must achieve a minimum grade of 50% on the final examination to pass the course. Scene Analysis Please note the new page and line references for the assigned scenes for analysis (The Wadsworth Anthology of Drama, 5th ed.): A Doll House, page 566, line 283 to page 568, line 495. Major Barbara, page 694, line 534 to page 696, line 692. The Cherry Orchard, page 649, line 227 to page 650, line 359. Scene Analysis Online Learning Object You may access audio enactments of these scenes through the course website – online resources: http://www.athabascau.ca/courses/engl/304/resources.html Please note the following amendment to the Study Guide Study Guide Act I Reading Assignments, page 18 and page 40: These essays are not in the fifth edition of the Wadsworth Anthology. Act III Objectives, page 93 Omit objective 7. #543262 November 20, 2006 Substitute the following objective for objective 13: Investigate the anti-apartheid and anti-racial strategies in “Master Harold” . . . and the Boys by Athol Fugard. Readings, page 94 Timberlake Wertenbaker, Our County’s Good is now a separate text; it is not included in the 5th edition of The Wadsworth Anthology. Eliminate the reading by Jack Davis: No Sugar; it is not in The Wadsworth Anthology. Athol Fugard, Valley Song has been replaced by “Master Harold” … and the Boys. Colonialism and Neocolonialism in Australia (pp. 105-108) Omit this section. South African Resistance and Reconstruction Athol Fugard – Valley Song (pp. 121-123) Please substitute the following material on “Master Harold” … and the Boys: Athol Fugard -- “Master Harold” . . . and the Boys Fugard is, without doubt, the most widely known South African playwright. During the apartheid era, he worked with black actors to produce plays that challenged the laws proscribing interracial collaboration in the theatre and exported them to England and the United States to bring an awareness of systemic racism which may be present in any country. He was born in 1932 in Middleburg, Cape Province, and when he was three, his family moved to Port Elizabeth in Eastern Province. His Afrikaans-speaking mother supported the family by running the Jubilee Hotel and the Saint George’s Park Tea Room; his Anglo-Irish father was incapacitated by alcoholism and a physical disability. Fugard studied at the University of Cape Town, but dropped out after three years to work as a sailor, journalist and court clerk. He became increasingly aware of the racial inequities that pervaded his society. When he began writing plays, he was influenced by the passionate, angry plays of British playwright, John Osborne, #543262 November 20, 2006 who was also sensitive to class inequities in British society. Fugard worked with the black actor Zakes Mokae to write, direct, and perform in four, two-actor plays: The Blood Knot (1963), People are Living There (1969), Boesman and Lena (1969), Hello and Goodbye (1971). With the Serpent Players in Port Elizabeth, a company that included white, black, and Asian Africans, he developed plays through improvisation. Two members of the company, Winston Ntshona and John Kani, contributed significantly to the development of The Island and Sizwe Bansi Is Dead (1972). With Statements after an Arrest under the Immorality Act, an indictment of the law that prohibited interracial marriages, they comprise the trilogy published under the title Statements. Many of Fugard’s plays are autobiographical, including “Master Harold” . . . and the boys (developed in the Market Theatre, Johannesburg in 1982), but they consider a range of points of view–from an aging artist in The Road to Mecca (1984), to young students in My Children! My Africa! (1989). Typically in his plays, the racist underpinnings of South African society undermine or destroy interpersonal relationships. While the plays deplore the exploitation of the black majority, they also point to the dehumanization of the white minority that perpetuates an unjust system. Valley Song (1996) is Fugard’s first post-apartheid play. According to Loren Kruger, “Fugard’s contribution is noteworthy not just because he has been the most widely published and produced playwright from South Africa but rather because he was the first to create on stage a fully colloquial South African English, as opposed to the self-conscious literariness that affects [other] writers . . . Shaped by the Afrikaans that many of his characters would plausibly speak more readily than English ... Fugard’s mature plays created a South African idiom that could be national, local, and intimate all at once” (20). Reading Assignment Athol Fugard, “Master Harold” . . . and the Boys. Study Questions 1. In what sense is Sam a surrogate father for Hally? 2. Why does Hally turn against Sam? 3. What are the consequences? #543262 November 20, 2006 4. What does the image of the dance signify? 5. What are the characteristics of a “Man of Magnitude”? 6. What are the chances of a “happy ending”? “Master Harold”…and the Boys begins with the aspirations of two black men to win a ballroom dance competition, although there are indicators that because of Willie’s treatment of his partner, he is unlikely to win. The entrance of Hally, whom they address as Master —an indicator of their compromised relationship with him—disrupts their practice, and it becomes increasingly obvious that despite his age, he assumes a position of authority. Although he states that he believes in social progress and the possibility of a social reformer who will rectify injustices, Hally soon demonstrates his own inability to live up to his ideals. His friendly camaraderie changes to threats and cruelty when he learns that his father will be coming home from the hospital, disrupting an already precarious home life. He takes out his frustration on the black men, who cannot respond to him in kind. He displaces Sam from his position as a nurturing, positive surrogate father, and claims as his true father an ignorant bigot. Fugard’s play also demonstrates an ironic role reversal. Although Hally, from his privileged position as an educated white boy has been “teaching” Sam, in the end it is Sam who instructs Hally on what it means to be a man. Hally remains a boy in his words and actions, and Sam demonstrates himself to be the “Master.” In effect, Sam is a “Man of Magnitude” —a Christian humanist hero. There are also suggestions in the play that he has Christ-like characteristics. His Christian sympathies are evident in his suggestion that Jesus Christ be considered a “Man of Magnitude”; like Christ, he has been whipped and persecuted, and he has carried Hally’s father like a cross on his back. He endures Hally’s spitting in his face and his betrayal of their friendship and forgives him in an attempt save him from his own demons. Echoing the words of Christ dying on the cross, Sam forgives Hally after telling him that he doesn’t know what he has done. Hally’s real father is, in effect, like a child: he compensates for his insecurities in identifying with the superheroes in comic books, such as Tarzan and Jungle Jim, who are white supermen, lording their supremacy over a primitive jungle culture. Willie’s views of himself and others have been shaped by the Western stereotypes of popular culture, including the glamorous Hollywood films of Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire. In the music of Count Basie and Sarah Vaughan, however, he adopts attractive black entertainers as his models, although in his own relationship with his #543262 November 20, 2006 dance partner, Hilda, he mimics the violent behaviour of the Brown Bomber. The image of ballroom dancing that introduces the play suggests social harmony and freedom— a world without collisions—as long as everyone agrees to dance to the same tune and in the same rhythm. Hally’s attitude to Sam and Willie’s dancing is, however, negative and patronizing. In his homework assignment, he intends to play up to the racist assumptions of his teacher in pointing out that “in strict anthropological terms the culture of the primitive black society includes its dancing and singing” (1446). Despite his learned prejudice, in the process of imaginatively creating the dance competition with Sam and Willie, Hally experiences the exhilaration of the movement and music and learns from Sam the human and social implications of “dancing like champions.” Despite the problems within, the play ends with Sam and Willie dancing, moving with a practiced (survival) skill through the cluttered tearoom that represents the complications of their society. The kite is another obvious image of freedom. Sam makes the kite in the servants’ quarters of the Jubilee Boarding House. In the Bible, Jubilee refers to a holy time occurring every fifty years when slaves were freed and land was returned to its original owners (Leviticus 25.8-12). Sam constructs the kite with skill and patience from two pieces of wood in the shape of a cross. He carries it up a hill where a “miracle happened.” These are also Biblical images associated with freedom. Significantly, the play is set in 1950. Self-test Review (p. 131) Omit numbers 4 and 6 and substitute the following quote for number 4 There’s no collisions out there, Hally. Nobody trips or stumbles or bumps into anybody else. That’s what that moment is all about. To be one of those finalists on that dance floor is like … like being in a dream about a world in which accidents don’t happen. #543262 November 20, 2006