Defendant`s Primary Skeleton Argument

advertisement

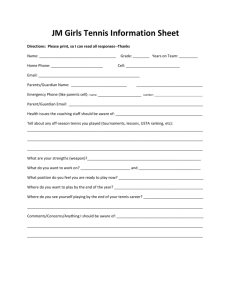

IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE QUEEN’S BENCH DIVISION B E T W E E N: Claim No. HQ09X01648 ROBERT DEE Claimant -vTELEGRAPH MEDIA GROUP LIMITED Defendant _______________________ DEFENDANT’S PRIMARY SKELETON ARGUMENT FOR HEARING ON 24 FEBRUARY _______________________ Reading list: Articles, application notice, witness statements, statements of case, skeleton arguments. D has prepared a separate skeleton argument in relation to the application of the single meaning rule. Estimated length of reading time: 2 – 3 hours Estimated length of hearing: ½ day to 1 day. Overview 1. This is a straightforward claim which has been overly complicated in an attempt to obscure its incurable defects. To use the metaphors of Lord Hobhouse in Three Rivers, what is required now is a focus on the “wood from the trees” and the “bottom line”.1 At a previous hearing Eady J observed: “It is difficult to see what the Claimant hopes to gain from this litigation. It may be true that the newspaper was "having a laugh" at his expense, but it is not immediately apparent how the claim is likely to restore or enhance his reputation”.2 On proper analysis, there is no rational basis on which the tribunal of fact could conclude that C has been libelled. There is no relevant conflict of evidence. The evidence served by C for this hearing is irrelevant to any of the issues to be determined. There is no need for a trial. The court is duty bound to grasp the nettle now and prevent further costs and court resources being applied to the claim. 1 Three Rivers DC v Bank of England (No 3) [2003] 2 AC 1 at [158] cited recently by Eady J in Ali v Associated Newspapers Ltd [2010] EWHC 100 (QB) at [12]. 1 2. C is now 23 years old. At 16 he left Eltham College, despite having apparently successfully completed his GCSEs and with no obvious success as a schoolboy tennis player, to be trained in Florida at a top private coaching establishment in the hope of achieving “great fame”. His strategy was “to gain my experience on the world circuit by playing any world ranking matches I could get into, anywhere I could and, in the process, hopefully see some of the world and gain valuable tournament experience”.3 The letter of claim states: “After attending Nick Bollettieri’s tennis academy in Florida in 2005, our client was advised by his coaches there to take advantage of the opportunity to play in ITF Futures tournaments primarily to gain experience of such tournaments at a higher level, notwithstanding that his prospects of winning such matches at that level would initially be negligible. That was a conscious strategy, which he was advised to follow by his coaches”. 4 It was C’s prerogative to pursue such a strategy and for his father to finance it. However, its consequences may properly be reported and commented on by the media. The claim 3. The claim arises from material published on the front page and page 20 of the Sport section of the issue of The Daily Telegraph of 23 April 2008 under the headings “World’s worst tennis pro wins at last” and “A British tennis sensation – the world’s worst”.5 To avoid unnecessary disputes about terminology, these will be described as “the front page article” and the “S20 article”. C’s claim relates solely to the front page article,6 but, in accordance with well-established principles, they must be read as one for the purpose of determining meaning. The articles reported that C had lost 54 successive tennis matches in straight sets in three years on the “circuit” or “international professional circuit”, which was the worst losing run. 4. C does not dispute the run of losses or that it was the worst. However, he states that over this period he was also participating in domestic tournaments in Spain (“the domestic Spanish tournaments”), that they were professional tournaments and that 2 Volume 1, tab 25 p242 at [5] See extracts of C’s website at Volume 1, tab 38 p306-307 4 LOC at Volume 2 p3 5 Articles at Volume 1, tab 16 p190-191 6 POC at Volume 1, tab 18 p194 3 2 he secured some modest victories in them.7 The domestic Spanish tournaments are outside the jurisdiction of the International Tennis Federation (“the ITF”), the world governing body of tennis and the Association of Tennis Professionals (“the ATP”), which organises the ATP World Tour and maintains the official international ranking system in men’s professional tennis. The domestic Spanish tournaments do not give rise to any world ranking points. This much is common ground. It is also clear that they are not part of “the circuit” or “the international professional circuit”, as these terms are commonly used in the tennis world. Throughout this litigation C has devoted much time and cost to aggrandising the Spanish tournaments and to obfuscating the clear distinction between them and world ranking tournaments on the international professional circuit. 5. Unsurprisingly, a large number of other media outlets covered the story. On 27 April C and Alan Dee gave an interview to The Sunday Times in which C stated that he felt “a little bit hard done by”. In contrast, Mr Dee was said to be “so angry...by some of the mocking articles written about his son that he sought the counsel of solicitors”.8 On 19 May Alan Dee registered the website www.robertdee.co.uk . In the biography section the following is attributed to C: “I never believed that by the time I was 21 I would have achieved great fame, I didn’t think I would be ready. But on 22 April 2008, my life changed forever. Having been previously unknown to almost everyone in the tennis world, I suddenly became famous overnight and that story you can read in another area!” 9 The other area includes the reproduction of a cheque from C’s solicitors for the sum of £12,500 from the BBC and a photograph of C with a cheque from ANL for £15,000.10 6. C’s solicitors (“AG”) sent a prompt letter of claim on 30 April 2008. It is noteworthy that the complaint, at this stage, related to both articles and identified the following meanings, which were derived from the words on S20:“That he unreasonably and unrealistically persists in a career as a professional tennis player which is an expensive waste of money and doomed to failure. That because of our client’s lack of success he is virtually unknown to the LTA.” 7 Volume 2 p3 Sunday Times article at Volume 1, tab 39 p311-312 9 Volume 1, tab 38 p307 10 Volume 1, tab 38 p308-310 8 3 There was also a claim for malicious falsehood.11 7. The correspondence petered out with a letter from D’s solicitors on 28 May 2008 offering, without admission of liability, a clarification in relation to the Spanish tournaments, which was not accepted.12 AG picked up the correspondence again in February 200913 and proceedings were eventually issued on 21 April 2009, shortly before the expiry of the limitation period.14 8. In the interim, C had commenced or threatened proceedings against a number of other publishers. They are referred to in the witness statements of David Engel, the supervising partner at AG,15 and Alan Dee in relation to this application.16 The fact that other publishers have capitulated in respect of different articles is irrelevant to the present application. It is, nevertheless, worth noting the evidence of Reuters’ solicitor, Keith Mathieson to the Parliamentary Select Committee. His observations also serve to underline the important policy factors in relation to CPR 24: “While I have got your attention, may I just mention one particular case I have had recently which shows the way in which CFAs operate in practice against the media. This was a case in which I acted for Reuters who were sued by a professional tennis player - not a well-known professional tennis player. His complaint was over a report that he had the worst record in professional tennis. This was not a desperately important story, nor was it a story which required much in the way of investigation or defence in the event that it was eventually to come to court. The tennis player employed his solicitors on a no-win no-fee basis. Reuters was extremely keen to defend the allegation. It thought that what it had published was basically true. There were, as there always are, slight niggles over aspects of the report, but basically Reuters was very keen to defend the case, and wanted to defend the case; it wanted to show that its journalists had done a proper job. Eventually it decided that it had really no option but to settle because it was faced with potential costs of trial for this comparatively unimportant libel case of £1.2 million. Those were the costs that it was going to have to pay the other side if it took the case to trial and lost. As you probably know, defendants do not have great record when it comes to taking cases before juries. So there was a clear risk even in a case where it was advised that it had a pretty strong case. It settled some four months before trial after the case had been going for five or six months; the costs that Reuters is now being asked to pay the other side are £250,000; that compares with Reuters' own costs of £31,000; so there is a massive disparity between the costs that are being claimed by claimant lawyers and the costs that are actually being charged to large international media organisations by firms such as mine.”17 11 Volume 2 p1-5 Volume 2 p23 13 Volume 2 p24 14 Volume 1, tab 17 15 Witness statement of David Engel at Volume 1, tab 15 16 Witness statement of Alan Dee Volume 1, tab 14 17 Volume 1, tab 46, p367-368 12 4 9. No explanation has been given of why The Telegraph is the Tail End Charlie. It seems inconsistent with the suggestion in Alan Dee’s witness statement that The Telegraph’s coverage was particularly damaging. A comparison of the media coverage would suggest that the substantial delay was for purely tactical reasons. Only The Telegraph referred explicitly to the Spanish tournaments and made clear that the 54 consecutive defeats were on the circuit and not in every tennis match that C played over the relevant period. No doubt, C’s advisors hoped that it would fold once the others had been picked off.18 10. The POC firmly limit the claim to the front page article. POC [4] advances the following meaning:“In their natural and ordinary and/or inferential meaning, the words complained of above meant and were understood to mean that until his win at the Reus tournament near Barcelona, the Claimant had lost 54 consecutive professional matches during his three years on the professional tennis circuit, and had therefore proved himself to be the worst professional tennis player in the world.” It is not clear why a distinction has been drawn between a “natural and ordinary” meaning and an “inferential” meaning. No legal innuendo is pleaded. 11. What is apparent from the pleaded meaning, is that C’s complaint is entirely dependent on his contention that the 54 consecutive defeats fail to take into account the domestic Spanish tournaments. Hence the phrase “54 consecutive professional matches” and the attempt to isolate the front page from S20, in which the reader is told that C had also been playing in tournaments on the “Spanish national tour”. There is no longer any attempt to contend that the humorous parts of the S20 article are unlawful. The complaint is limited to the run of 54 defeats and the suggestion that it ranks as the world’s worst. 12. The Defence denies that either article is defamatory and advances substantive defences of justification and fair comment in relation to the following meanings:“5.1. The Claimant lost 54 consecutive matches in straight sets in tournaments on the international professional circuit; and/or 18 See AG’s letter of 9 February at Volume 2 p24 5 5.2. The Claimant lost 54 consecutive matches in straight sets in tournaments that contribute to a player’s world ranking; 5.3. In consequence, he merited being ranked or described as the world’s worst professional tennis player.” These tournaments are defined in the Defence as “Eligible Professional Tournaments”.19 13. Subsequent to the Defence C has served a Reply and three Part 18 Responses.20 Each has sought to muddy the clear blue water between the Eligible Professional Tournaments and the domestic Spanish tournaments. In particular, C has raised pettifogging points in relation to minor amendments to the professional rules which have nothing to do with any of the issues raised by the claim. He has repeatedly failed to put his cards on the table in relation to the use of “the circuit”, “the word circuit” and “the international circuit”, notwithstanding the judgment and order of Eady J in this regard. Most recently, he has introduced the concept of an “ITF Futures Qualifying Draw Tournament”, in a misguided attempt to extricate 41 of his defeats from the 54. 21 These matters are addressed further below. 14. AG have submitted a costs estimate of over £500,000 excluding success fees and ATE insurance premium.22 Before proceedings were issued D offered a mutual costs cap of £50,000.23 Eady J noted that: “To an outside observer, it may seem difficult to understand how the case could give rise to such expenditure”.24 This is all the more so when AG have already managed to generate £250,000 against Reuters (the claim on assessment was, in fact, over £350,000), £28,000 against the BBC and no doubt further sums in relation to other publishers. These have all been directed to the same basic point in relation to the domestic Spanish tournaments. What is invidious about such massive costs, as Mr Mathieson and many judges have observed, is that they pressurise a defendant into settling unmeritorious cases on a purely commercial basis. In this context, CPR 24 is a salutary power. 19 Defence at Volume 1, tab 19 Reply at Volume 1, tab 20, Part 18 Responses at Volume 1, tabs 22, 23 &24 21 See 3rd Part 18 Response at Volume 1, tab 24 p237 at [13.1] 22 Volume 1, tab 35 p260-266 23 Volume 2 p31 24 Volume 1, tab 25 p242 at [5] 20 6 15. By this application D seeks summary judgment under CPR 24 in relation to the whole of the claim.25 This is on the basis that, in the event that the article/s are held to be defamatory of C, he has no real prospect of rebutting the justification and/or fair comment defence. Alternatively, it is submitted that the article/s are not capable of being defamatory of C. The various possible outcomes are considered further below. Essentially, whichever way C seeks to present his case, no tribunal of fact could rationally conclude that he has been libelled. 16. Part of D’s case is that the front page and S20 article must, as a matter of law, be read together for the purpose of determining meaning. However, it remains D’s case that even if the front page article is read in isolation, C still has no real prospect of success. D’s submissions in relation to this construction point are set out in a separate skeleton argument, as it will not be necessary for the Court to determine the point, if D’s submissions in relation to the front page article are accepted. Relevant legal principles 17. The burden placed on an applicant in a summary judgment application in a defamation claim is well established and is set out in Gatley at [32.30]. The most common obstacle to such an application is the existence of contested evidence which a jury could resolve in favour of the respondent. Where, in contrast, the issue is the conclusion to be drawn from admitted or incontrovertible facts, the court is in a better position to determine the matter summarily. Indeed, the court is duty bound to reject any unreasonable conclusion contended for by the respondent. If not, the applicant will be “wrongly burdened with defending libel proceedings [which]... can be a very onerous burden and one which interferes with the right of freedom of expression”.26 Where the costs are substantial it becomes all the more important for the Court carefully to scrutinise the viability of the claim at the interim stage. 18. The Court is reminded of the policy factors underpinning CPR 24:"It is important that a judge in appropriate cases should make use of the powers contained in Part 24. In doing so he or she gives effect to the overriding objectives contained in Part 1. It saves expense; it achieves expedition; it avoids the court's resources being used up on cases where this serves no purpose, and, I would add, 25 Application Notice at Volume 1, tab 1 Tugendhat J in John v Guardian News & Media Ltd [2008] EWHC 3066 (QB) at [16], cited by Sharp J in Ecclestone v Telegraph Media Group Ltd [2009] EWHC 2779 (QB) at [10]. 26 7 generally, that it is in the interests of justice. If a claimant has a case which is bound to fail, then it is in the claimant's interests to know as soon as possible that that is the position."27 It is very easy for a claimant to come before the court and argue that the claim is not sufficiently clear-cut and he is entitled to his right to a jury trial. It is important to ensure that the claimant is not deliberately and unnecessarily over-complicating matters and to focus on the issues that would properly fall to be determined if the case proceeded to trial. A failure to do so will frustrate the purpose of Part 24. 19. There have been a number of previous cases in which the court has upheld interim applications by defendants on the basis that the justification defence was bound to succeed on the basis of the admitted or incontrovertible facts.28 An appellate court may make a similar ruling after a trial.29 The issue is always whether there is any rational basis on which the tribunal of fact could conclude that the publication was not true or substantially true. 20. D’s primary case is that the article is wholly true in any defamatory meaning that it is capable of bearing. However, if it is necessary to consider substantial truth, reference should be made to the principles set out by Eady J in Turcu v News Group Newspapers Ltd [2005] EWHC 799 (QB) at [108-111]:108. ….. It is necessary to remember what has been said more than once in the European Court of Human Rights to the effect that journalists, in the exercise of their rights to freedom of expression, need to be permitted a degree of exaggeration even in the context of factual assertions (not only when making comments or voicing their opinions): See e.g. Bladet Tromsø & Stensaas v Norway (1999) 29 EHRR 125 at [58][59]; Reynolds v Times Newspapers Ltd [2002] 2 AC 127, 204. 109. As was suggested in Branson v Bower (No. 1) [2001] EMLR 800 at [8] and in Berezovsky v Forbes Inc [2001] EWCA Civ 1251 at [9], English law is generally able to accommodate the policy factors underlying the Article 10 jurisprudence by means of established common law principles; for example that a defamatory allegation need only be proved, on a balance of probabilities, to be substantially true. The court should not be too literal in its approach or insist upon proof of every detail where it is not essential to the sting of the article. So too the demands of a defence of justification are sometimes mitigated by the terms of section 5 of the Defamation Act 1952 (although not of relevance here). 27 Lord Woolf MR in Swain v Hillman [2001] 1 All ER 91, 94 cited in Ali at [13] See for example Johnson v Perot Systems Europe [2005] EWHC 2450 QBD at [114], Robson v News Group Newspapers Ltd Unreported 9 October 1995 HHJ Previte QC and Ali v Associated Newspapers Ltd [2010] EWHC 100 (QB). 29 See Gatley at [38.19]. 28 8 110. Each case obviously depends on its own unique circumstances and the application of these considerations of public policy will to a large extent be a matter of impression. Here, Mr Price contends that the gap between what was published about his client and the facts established at trial is simply "unbridgeable". He reminded me also of the words of Simon Brown LJ in Grobbelaar v News Group Newspapers [2002] All ER 437 at [40]: "If the newspapers choose to publish exposés of this character, unambiguously asserting the criminal guilt of those they investigate, they must do so at their own financial risk". True no doubt, but it does not assist when one comes to decide on the particular facts. 111. In deciding whether any given libel is substantially true, the court will have well in mind the requirement to allow for exaggeration, at the margins, and have regard in that context also to proportionality. In other words, one needs to consider whether the sting of a libel has been established having regard to its overall gravity and the relative significance of any elements of inaccuracy or exaggeration. Provided these criteria are applied, and the defence would otherwise succeed, it is no part of the court's function to penalise a defendant for sloppy journalism – still less for tastelessness of style. I must set all that to one side, including what Mr Price described as the "orgy of self-congratulation", and focus only on substance. 21. Where the facts upon which the defendant relies are uncontested and/or clearly true, but the claimant relies on other facts which he contends bear on the substantial truth of the publication, the court must ask whether the tribunal of fact could rationally conclude that the facts relied on by the claimant make any difference to the court’s conclusion on the basis of the uncontested facts relied on by the defendant. 30 Putting it another way, do the facts advanced by the claimant (even assuming them to be true) materially affect any defamatory impression conveyed by those relied on by the defendant in the context of the publication complained of? On what rational basis could the facts advanced by the claimant render the publication libellous? 22. Where a publication is only barely defamatory, an error or exaggeration is less likely to be materially defamatory. 23. The determination of truth or substantial truth may be linked to the determination of meaning. However, any potential differences in meaning between the parties must a) have the capacity to make a difference to a rational decision on truth or substantial truth and b) the claimant’s meaning must be a capable meaning. The articles 24. For convenience, both articles are set out below. 9 Front page “World’s worst tennis pro wins at last By Mark Hodgkinson A BRITON ranked as the worst professional tennis player in the world after 54 defeats in a row has won his first match. Robert Dee, 21, of Bexley, Kent, did not win a single match during his first three years on the circuit, touring at an estimated cost of £200,000. But his dismal run ended at the Reus tournament near Barcelona as he beat an unranked 17-year-old, Arzhang Derakshani, 6-4, 6-3. Dee, below, lost in the second round. Full story: S20: Page S20 “A British tennis sensation – the world’s worst British globetrotter Dee ends his losing streak at the 55th time of asking, writes Mark Hodgkinson. IN the history of British tennis failures, and it’s been a long and rich history, no one had previously come close to the serial defeats that have flowed from the racket of Robert Dee, a 21-year-old from Bexley, Kent. Perhaps Dee has earned the right to be bracketed with such global sporting icons as ski-jumping’s Eddie the Eagle or swimming’s Eric the Eel. Dee said last night he had found his new fame “a bit odd”, but raise a glass of Pimm’s to him, as when it comes to losing he’s absolutely world class. Dee recently equalled the world record for the longest run of consecutive defeats, after his first three years on the international professional circuit saw him lose 54 matches in a row, and all of them in straight sets. That’s 108 lost sets in succession. Dee sounded baffled yesterday as he reacted to claims that he might just be the world’s worst professional tennis player. “I honestly didn’t know about the record so all the attention is a bit odd,” he said. “Obviously it was great to get my first win but I can’t believe that people don’t have anything better to write about. I’m just going to keep on playing and improving and working hard with my coaches. Hopefully that will mean more wins at these sorts of tournaments.” His father Alan, said that describing him as a total no-hoper “was laughable and incorrect”, adding: “The Lawn Tennis Association have given him a rating of 4.2 and that is very impressive.” Paul Henderson, his former head teacher at Eltham College, said: “Rob was never the school champion but he was very methodical about his tennis. We often wondered if we would hear of him again.” Dee has lost around the planet, in Iran, Senegal, Colombia, Botswana, Venezuela, Rwanda, Kenya, Sudan, Mexico, the United States, Norway, Holland and Spain. Almost all of his tennis has been played at Futures tournaments, which are the lowest rung of the proper professional circuit. Dee’s travel expenses must run to hundreds of thousands of pounds. And yet he has won a fraction of that back in prize money. Why didn’t he just give up, you might ask. But you also have to admire Dee’s perseverance as his losing record went on and on and expensively on. A spokeswoman for the LTA confirmed yesterday that Dee had not received any official 30 See for example Ali above, and by analogy the approach of Eady J in Branson v Bower (No2) [2002] QB 737. 10 funding, and instead received money from his parents, with his father a managing director of a shipping firm. Dee’s lack of success means that he doesn’t have a proper world ranking and until this week the LTA knew next to nothing about him. Even the Kent county office were largely in the dark, regarding Dee as something of a jet-setting man of mystery, whose long-awaited win came in Spain last week when he beat American Arzhang Derakhshani 6-4, 6-3. But he was brought down to earth when he immediately lost 63, 6-1 to Poland’s Artur Romanowshi. Dee is now living and training in La Manga, Spain, and in recent months has been playing tournaments on Spain’s national tour. Apparently, he’s even threatening to break into the top 500 of players based there. Roger Federer, beware. National failings 1 Eddie “the Eagle” Edwards In 1998, became Britain’s first and only ski jumper to reach the Winter Olympics – he had no rivals and was the only British option. At 20lb heavier than nearest competitor, he finished last in the 70m and 90m events. 2 England cricket team 2006 – 07 After the euphoria of winning the Ashes the previous summer, Duncan Fletcher’s men became 5-0 whipping boys Down Under. 3 Devon Loch Dick Francis was cruising to victory in the 1956 Grand National when the Queen Mother’s horse slipped and collapsed yards from the winning line. 4 England’s Euro 2008 squad Steve McClaren, the ‘wally with the brolly’, couldn’t lead England’s ‘golden generation’ to the finals. Failure to reach a major tournament for the first time since the 1994 World Cup may cost the British economy £2billion.” The uncontested and incontestable facts 25. The following facts are admitted by C (although this may not be not be immediately apparent from the Reply and the Part 18 responses):a. The run of 54 defeats were in tournaments that are under the jurisdiction of the ITF or ATP. b. They are all world ranking tournaments. c. It is the worst ever run of defeats in such tournaments. d. The domestic Spanish tournaments are not under the jurisdiction of the ITF or ATP and are not world ranking. 26. In relation to b. above, this is admitted by virtue of paragraph 5.12 of the Defence, paragraph 26 of the Reply and Responses 3 to 5 of the Part 18 Response of 24 July. However, in the Part 18 Response of 20 November, signed by C, he sought to introduce the concept of “ITF Futures Qualifying Draw Tournaments” as comprising 11 separate tournaments from the Main Draw.31 50 of C’s defeats were in Futures tournaments and 41 were in Qualifying Draws. Success in the Qualifying Draws does not, of itself, lead to the award of world ranking points. C’s purpose is to extract 41 of his defeats from his record in world ranking tournaments. 27. The short answer to this point is that what matters is whether the tournament is capable of giving rise to world ranking points, not whether every person who plays in it does end up winning points. The fact that the C was unable to make it past 41 Qualifying Draws is hardly something that should assist his case. Moreover, all the evidence conclusively demonstrates a) that the Qualifying and Main Draws are part of the same tournament, as C has recognised by his own public statements and b) that the first known use of the term “ITF Futures Qualifying Draw Tournament” was in C’s Part 18 Response.32 Accordingly, it is clear that a player in a Qualifying Draw is participating in a world ranking tournament. 28. The facts identified in paragraph 23 above are sufficient to justify any defamatory meaning that the words are capable of bearing, including that advanced by C. 29. Furthermore, on the evidence before the Court, it is incontestable that the 54 defeats were on “the circuit”, “the word circuit” and/or “the international professional circuit” as such terms are commonly used.33 As Eady J recognised, this issue is directed to justifying what was published; not to adducing evidence in relation to meaning. C has repeatedly refused to engage with the issue, notwithstanding Eady J’s order requiring him to “put his cards on the table”. A careful analysis of the Reply and the three Part 18 Responses reveals that C accepts that the terms have “various meanings and can be used in different contexts” but denies that they are in commonly usage in the manner contended for.34 C has chosen not to elucidate the “various meanings”. 31 Response 13 confirmed by AG letter of 15 January at Volume 2 p143 See the second witness statements of Bruce Philipps at Volume 1, tab 6, Jackie Nesbitt at Volume 1, tab 7 and the first witness statement of Julia Varley at Volume 1, tab 8 33 See witness statements of Chris Kermode at Volume 1, tab 2, Barry Cowan at Volume 1, tab 3, Boris Becker at Volume 1, tab 4, John Lloyd at Volume 1, tab 5 and the second witness statement of Bruce Philipps at Volume 1, tab 6. 34 See [9 – 17] of 1st response at Volume 1, tab 22 p225-226 32 12 30. D has adduced witness statements from 5 eminent witnesses (including one of C’s) which clearly and indisputably make good D’s case in regard to the common use of the relevant terms. 31. C’s evidence in response is extremely limited, carefully worded and (in accordance with his approach to the statements of case) striking by what is not said. C states at [19]: “..there is no particular word or phrase which I would use, or which I think is generally used in tennis, to distinguish ITF sanctioned tournaments from other professional tournaments organised by the RFET or, for example, by the LTA in Great Britain. The Defendant says that the phrase “international professional circuit” is in common usage to distinguish ITF sanctioned tournaments from other professional tournaments and circuits, but I have never heard this term being used”. C once again refuses to state his understanding of “the circuit” or “the word circuit”. This is notwithstanding his publicly stated strategy of gaining “experience on the world circuit by playing any world ranking matches” [emphasis added].35 Daniel Dios, C’s Spanish coach, says that he has never heard the term “international professional circuit”.36 Somewhat elliptically, he states that in his experience the terms “the circuit” or “the word circuit” do not have any special meaning. This is not an answer to the unambiguous evidence served in support of the application. Mr Engel simply exhibits the outcome of a search of material written by Mr Hodgkinson, which, on analysis, supports D’s case. 37 32. It is notable that, notwithstanding that C’s evidence is supposed to be in reply to D’s, AG did not show D’s witness statements to their witnesses. C’s evidence fails to put forward any alternative meaning of “the circuit”. This is evidently a widely used shortened form of “the international professional circuit”, which was used in the front page article. 33. C’s attempts at expensive obfuscation on this issue should end now. This is an adversarial contest. C has had two months to respond to D’s witness statements and four statements of case in which to set out a proper case. On the evidence before the Court, the only finding reasonably available to the tribunal of fact at trial is 35 Witness statement of C at Volume 1, tab 9 p50 Witness statement of Daniel Dios at Volume 1, tab 10 p68 at [24] 37 Volume 1, tab 15 36 13 that the tournaments in which the Claimant had the losing run of 54 defeats were part of “the circuit” and/or “international professional circuit” (as such terms are commonly used in relation to the profession of tennis) and that the domestic Spanish tournaments were not. The Court is duty bound to make this finding now. Matters that are irrelevant 34. C has directed considerable time and cost to aggrandising the standard and status of the domestic Spanish tournaments in an attempt to put them on a par with ITF Futures tournaments. One might think that the very fact that he secured some victories in the domestic Spanish tournaments while consistently losing in straight sets in ITF Futures matches would suggest that the standard was radically lower. Moreover, C’s public statements have drawn a clear distinction between the two types of tournaments. For example, he referred to an ITF Futures victory in April 2008 as “his first win”, notwithstanding he had been playing in domestic Spanish tournaments for some time and stated: “I’m just going to keep on playing and improving and working hard with my coaches. Hopefully that will mean more wins at these sorts of tournaments”.38 His letter of claim acknowledged that the ITF Futures tournaments were at “a higher level” and “his prospects of winning such matches at that level would initially be negligible”.39 35. The outcome of this libel claim cannot turn on an assessment of the respective standards of play in the domestic Spanish tournaments and ITF Futures tournaments and C’s evidence in this regard is irrelevant. 36. C also seeks to establish that the domestic Spanish tournaments are professional tournaments. Attempts by D in correspondence to establish what C means by “professional” have not proved fruitful.40 The ITF appears to accept that where prize money is offered they will regard them as professional.41 It also appears that some of C’s victories were in tournaments where prize money was available. It does not appear that C has ever won any prize money. 38 Volume 1, tab 38, p306-307 Volume 2 p1-5 40 Volume 2 p117-120 41 See first witness statement of Jackie Nesbitt at Volume 1, tab 11 p134 at [7] 39 14 37. The precise status and standard of the domestic Spanish tournaments are irrelevant to the proper determination of this claim. For the reasons set out below, the only relevant facts are that they are not sanctioned by the ITF or ATP, do not give rise to world ranking points and (insofar as is necessary) they are not part of “the circuit” or “the international professional circuit”. Insofar as is necessary, it is submitted that, whatever the standard, they are clearly of far lesser status than ITF/ATP tournaments. The application of the principles to the facts Justification bound to succeed 38. The pleaded meaning can be divided into two allegations. Firstly, that C had lost 54 consecutive professional matches. Secondly, that he has proved himself to be the worst professional tennis player in the world. It is not clear whether the alleged run of losses is alleged to be defamatory in its own right or that it is merely the link to the allegation that he is the world’s worst. It will be assumed that C contends that both allegations are defamatory. 39. Put shortly, the fact that C lost 54 matches in a row in straight sets in his first three years in world ranking ITF/ATP tournaments on the international professional circuit and that this was the worst ever run, is, on any rational basis, sufficient to justify any defamatory impression arising from anything that was said in the article/s about C’s playing record. 40. There is no additional obligation on D to prove that C is objectively the worst professional tennis player in the world in terms of his playing skills. The article is not capable of bearing such a meaning. It is clear to the reader that the characterisation of C as the world’s worst tennis player is simply a consequence of his unprecedented record of defeats. Moreover, POC [4] also links the “world’s worst” allegation to the playing record. 41. To subject D to a “penalty” in defamation if it could not prove objectively that C was the world’s worst player, would also be contrary to the “policy factors underlying Article 10” identified in Turcu. It would be impossible to prove; how would a jury objectively determine playing skill and what would be the cut-off point in determining whether a comparative player was a professional? It would also unnecessarily inhibit the 15 reporting of statistics in competitive sport to require proof of objective qualitative factors (which may be impossible to prove) in addition to raw data of performances. 42. Alternatively, insofar as the “world’s worst” is found to be a value judgment, it is clearly fair comment.42 43. Does the fact that C won matches in the domestic Spanish tournaments during the same period make any difference? The only rational answer is that, for a number of reasons, it cannot. a. Even if the front page is seen in isolation, it is not capable of being understood to refer to all matches played by C during the period. It is obvious from the references to “ranked as the worst professional tennis player in the world” and the “circuit” that the consecutive defeats were in tournaments contributing to a world ranking. The ordinary meaning of “circuit” in a sporting context, which would be known to the ordinary reader, is a series of competitions held in different places. The use of “the circuit” suggests that it is a recognised term in tennis. There is no reason for an ordinary reasonable reader, who is unaware of its technical meaning, to conclude that “the circuit” equates to all matches played over the period. b. Furthermore, the S20 article explicitly refers to the domestic Spanish tournaments, thereby drawing a clear distinction between them and those on the international professional circuit: “Dee is now living and training in La Manga, Spain, and in recent months has been playing tournaments on Spain’s national tour. Apparently, he’s even threatening to break into the top 500 of players based there”. The ordinary reader does not have know anything about tennis to understand that “the tournaments on Spain’s national tour” are not part of the international professional circuit. Moreover, “international” is in obvious in contrast to “national”. Readers are also told that “Dee recently equalled the world record for the longest run of consecutive defeats, after his first three years on the international professional circuit” and that following his “first win” he hopes to achieve “more wins at these sorts of 16 tournaments” [emphasis added] i.e. those on the international professional circuit. c. Even if the domestic Spanish tournaments are properly to be regarded as professional and an ordinary reader is capable of understanding the article/s to mean that C had lost 54 consecutive professional matches, it would still be unreasonable to find that the article/s were libellous. i. No rational tribunal of fact when informed of the admitted facts (alternatively, the admitted and incontrovertible facts) could conclude that the failure to include the domestic Spanish tournaments in C’s professional record gives rise to a material defamatory falsehood in the context of a) any defamatory impression of C drawn from the article/s (insofar as it relates to his playing record) and b) any defamatory impression of C drawn from the truth. ii. The only defamatory sting (if there is one) is that C has lost a very large number of tennis matches and, in particular, the longest record of consecutive defeats in the world. This is indisputably true. The tournaments that comprise the record are based on rational grounds (and the only record available). The ATP ranking system is the world ranking system. There is no world ranking system that also takes into account performances in non ITF/ATP tournaments. The fact that C won some matches in lesser status tournaments in Spain during the same period, does not detract from the fact that he holds the longest record for consecutive defeats based on the official world ranking system. iii. As Eady J held in Turcu at [111]: “In deciding whether any given libel is substantially true, the court will have well in mind the requirement to allow for exaggeration, at the margins, and have regard in that context also to proportionality. In other words, one needs to consider whether 42 In accordance with the principles in set out in Branson v Bower (No.2) above. 17 the sting of a libel has been established having regard to its overall gravity and the relative significance of any elements of inaccuracy or exaggeration. Provided these criteria are applied, and the defence would otherwise succeed, it is no part of the court's function to penalise a defendant for sloppy journalism – still less for tastelessness of style. I must set all that to one side, including what Mr Price described as the "orgy of self-congratulation", and focus only on substance”. On the assumption that the ordinary reader understood the article/s to imply that the run of 54 defeats were in all professional matches, at the worst there has been a failure to clarify terminology that amply falls within the permitted degree of tolerance recognised in the domestic and European authorities. It goes without saying that the “having a laugh” factor – which is not now complained of – must be put to one side. The focus is solely on substance. iv. Put in the words of a layman apprised of the true facts, the only rational response to C’s protestation that he won some matches in Spain is: “So what? What matters is that you lost 54 matches in ITF/ATP world ranking tournaments on the international professional circuit in a row and in straight sets and that is the worst ever run of defeats. The Spanish tournaments are not ITF or ATP tournaments, they are not world ranking or part of the circuit”. v. This determination can and should be made at the interim stage as there is no relevant conflict of evidence. 44. Moreover, any libel penalty based on a finding that an ordinary reader would not understand the meaning of “the circuit” or “the international professional circuit” would be contrary to Article 10. It is a settled part of the Strasbourg jurisprudence, approved by the House of Lords, that the form in which information and ideas are expressed is generally for the publisher to decide, without interference from the domestic courts.43 The media is entitled to exercise its own judgment in the 43 See for example Jersild v Denmark [1994] ECHR 33 at [31] cited with approval by Lord Hoffmann in Campbell v MGN Ltd [2004] AC 457 at [108]. 18 presentation of journalistic material. The present case relates to article/s about tennis. Mr Hodgkinson has chosen to employ terms, which, on the evidence, are in common use in the tennis world and which have been used correctly by him. Implicit in any finding of libel, on C’s case, would be that the ordinary reader did not understand precisely what is meant by them and therefore failed to understand the true nature of C’s serial defeats. The ordinary reader is a device to control liability.44 He fails in this process if a deemed lack of knowledge gives rise to a finding in libel in a case where the journalist has expressed lawful information and ideas in a form appropriate to the subject matter and clearly within the discretion afforded to him. Not capable of being defamatory 45. There is under English law no general cause of action for the publication of false statements in the media or elsewhere. In cases involving newspapers, the Press Complaints Commission’s Code of Conduct may provide some remedy. Where the statement is calculated to cause financial loss and published maliciously, a claim in malicious falsehood will be available. Modern developments in harassment, privacy and data protection have provided additional remedies in appropriate circumstances. However, it is an unavoidable requirement for a claimant in a defamation claim to demonstrate that the statement in question is defamatory of him. In the modern era, the appropriate threshold must be interpreted consistently with the “necessity” requirement in Article 10. Setting the bar too low devalues the tort.45 46. As previously stated, C does not attempt to allege that the arguably humorous parts of the S20 article expose him to ridicule.46 The complaint is limited to the run of 54 defeats and the suggestion that it ranks as the world’s worst. 47. The risk of defeat is an inevitable part of sporting competition, particularly for a young player in the first years of competition. It cannot be defamatory to state that a player has lost a tennis match. If it cannot be defamatory to state that a player has lost one match, why should it be defamatory to state that he has lost a large number on the 44 See Gatley [3.25] fn 256. See the approach of Sharp J in Ecclestone above. 46 An exposure to ridicule generally arises from an imputation of some conduct on the part of the claimant that would make right-thinking people think the worse of him. It is questionable whether absent of such an imputation, the publication should be actionable, particularly in the light of developments in misuse of private information and harassment. 45 19 trot? The risk of consecutive defeats is an equally inevitable part of sporting competition, as is the fact that someone has to have the worst playing record over a particular period. 48. There appears to be no previous case in which a sportsman has sued in defamation in relation to a statement concerning his playing record. None of the cases referred to in Gatley [2.35] are on point. The majority involve allegations which involve moral blame. The editors suggest at [2.26], as a general test in relation to allegations concerning “business, trade or profession”, that the “words must impute to the claimant some quality, which would be detrimental, or the absence of some quality which is essential, to the successful carrying on of his office, profession or trade”. (It may be that this test is too favourable to a claimant in that it might include certain allegations such as a physical injury which would obviously not be defamatory). 49. It does not follow from the fact that a young tennis player has lost a large number of consecutive matches in his first years that he lacks an “essential quality” to be a professional. The article records the fact that C has won his first match and his intention to add to his success. It is clear that he is continuing with his career and there is no suggestion in the article that he lacks any essential quality to make it work. Nothing is said about the reason for his defeats. No defect in his play is identified. POC [4] does not suggest that the article imputes any incompetence to C, notwithstanding the pleader’s stated intention to cover inferential meanings. 50. The limited part of the article of which C complains says nothing about his character and is incapable of lowering his estimation in the mind of a right-thinking person. One of the meanings identified in the letter of claim was that C “unreasonably and unrealistically persists in a career as a professional tennis player which is an expensive waste of money and doomed to failure”. Since this meaning is not complained of in the POC and can only be derived from the words on page 20, it cannot be taken into account. But it is worth observing in passing, that perseverance in the face of adversity is a longstanding British characteristic which is to be admired by a right-thinking person. David Price Solicitor-Advocate for the Defendant 23 February 2010 20