Call for papers - Memory before Modernity

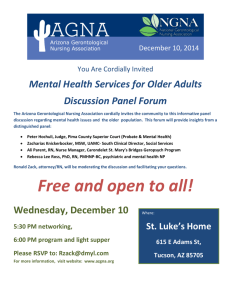

advertisement

Call for papers Memory before Modernity. Memory Cultures in Early Modern Europe Leiden University, The Netherlands 20-22 June 2012 In the ‘memory boom’ that has emerged in the humanities and social sciences since 1990, five major themes have captured most attention: (a) the relationship between politics and memory, (b) trauma and memories of violence, (c) the ‘mediatization’ of memory (d) the transmission of memory and identity formation (e) the relationship between memory, history and other concepts of the past. Yet most case studies relating to these themes have been concerned with events and evidence post-1800; indeed, many theorists of memory allege that there is something intrinsically ‘modern’ about them. The aim of this conference is to put this assumption to the test. First, we want to ask to what extent, and in what ways, these five themes also played themselves out in the early modern period. Secondly, we want to analyze more closely how early modern cultural, social, political and religious frameworks affected cultures of memory. Who ‘managed’ early modern memories? What mechanisms were at work? What patterns can we establish? How distinctively ‘early modern’ are these? We invite late medievalists and early modernists to offer proposals for 20 minute papers on one of the following five themes. Details on the panels can be found below Panel Panel Panel Panel Panel 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Memory wars before the nation state Coping with distressing memories Memory landscapes as multimedial experiences Memory transmission and identity formation Sensations of change The themes will be introduced in five keynote lectures. Confirmed keynote speakers include Philip Benedict, Susan Broomhall and Benjamin Schmidt. The conference will end with a round table in which experts on modern memory will comment on the findings of the conference. We will be able to cover the expenses of economy travel and accommodation in Leiden for all speakers selected. Papers should be submitted two weeks before the conference and will be made available to all participants beforehand. Proposals can be submitted until 1 November 2011 by email: emm@hum.leidenuniv.nl This conference is organized by the NWO VICI Research Team Tales of the Revolt. Memory, Oblivion and Identity in the Low Countries, 1566-1700, that is directed by Professor Judith Pollmann. Further information on the team and the project at www.earlymodernmemory.org Panel 1. Memory wars before the nation state David Cressy’s seminal work on national memory in Elizabethan and Stuart England, Bonfires and Bells (1989), attributes a central role to the state as a driving force in early modern memory formation. Governments could influence memories of the past in order to bolster their political agendas. But the state was never the sole manipulator of memory and sometimes not even a necessary actor. Pressure groups, 1 such as Huguenots in seventeenth century France, could defy dominant government readings of the past. In the resulting ‘memory wars’, these opposition groups deployed counter-memories in support of their own political aims. Moreover, in decentralized states such as the Dutch Republic or Poland, political appeals to feelings of togetherness in (new) national communities drew on the reconstruction of a real or imaginary ‘national’ past. They became increasingly important to marshal support for public projects that could not be carried out merely on a local scale, such as the protection of an endangered church, the restoration of a challenged dynasty, and/or alternative attempts of national consolidation. Memory practices had a major impact on the forging of new ‘national’ identities during the religious, civil and dynastic upheavals in Reformation and Counter-Reformation Europe. In the great variety of early modern European polities of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, much depended on the political system in which memory was being manipulated. But regardless of the political system, identities did not simply arise organically in the passing of time. They were also the products of memory wars: conflicts between competing pressure groups who derived authority by invoking memories of the past. Contributors to this panel are therefore asked to consider under what conditions ‘national’ canons of remembered history could come into existence and who were the most important actors, to explore what kind of political conflicts between rivaling factions could be fought out with memories of the past, and to map out subverting mechanisms employed by government authorities and pressure groups to ensure that undesirable parts of history did not countermand their political agendas. Panel 2 Coping with distressing memories During early modern wars populations at large were confronted with violence and life-threatening situations. The countryside suffered from pillaging troops while many town dwellers experienced sieges and sacks,Many also experienced abuse, harassment and violence from fellow citizens in different confessional or political camps. Today, we are conscious that victims of violence or natural disasters may carry on their distressing memories for the rest of their life. The psychological damage of traumatic experience is considered to be important, because it can lead to a great variety of symptoms and functional impairments even in subsequent generations. Yet, we also know that the way people cope with these memories may vary across cultures. Research suggests that coping strategies that manage to give some sort of meaning to a traumatic experience are the most effective in preventing the development of severe psychological disorders. The central question in this part of the conference is whether our sources allow for a characterization of early modern coping strategies. Of course this question is difficult to answer for a number of reasons: Sources are lacking, do not provide the necessary information, are not representative or are for other reasons very hard to interpret. Still, the participants of this panel are encouraged to develop creative methods to work around these problems. Except for personal documents like diaries, memoires, autobiographies, and letters, we would like to explore the potential of non-literary accounts like chronicles, judicial accounts, testimonies, and attestations, claims, requests and petitions sent to public institutions and authorities. In addition, texts with autobiographical content or reported eyewitness accounts can be studied: histories and chronicles of war and journals. While early modern narrative conventions may have precluded the expression of individual emotion so central to modern war memoirs, this neither means that these feelings were nonexistent, nor that these texts did not serve a purpose in the process of coping or coming to terms with the past. Instead we may need to ask what these texts do 2 express, keeping in mind that writing down or narrating one’s memories is a social act and thus reflects what is to be meaningful for both the author and the (intended) audience. Panel 3 Memory Landscapes as multimedial experiences Modern memory scholars often present the development of mass media as a condition for the circulation of collective memory. Undeniably, through media such as photographs, films and postcards it became easier to reach a larger part of the population than in the early modern period. Yet, while mass media did not develop until the nineteenth century, early modern societies can be characterized as multimedial. Early modern memory scholars have already shown that a wide array of older media such as paintings and prints, pamphlets and sermons, songs and rituals, could also be used to transmit, create and manipulate public memory, and to great effect. By integrating a range of media into the study early modern memory, and by exploring the multimediality of early modern societies, research makes it possible to map a so-called ‘memory landscape’. Besides a focus on elite media such as paintings, books and tapestries this approach also includes material objects, places of memory, and archeological evidence. Analyzing these artifacts in cohesion produces a different reading of early modern memory cultures, because it looks beyond the boundaries of the memory cultures of elites and authorities. A focus on media and their interaction therefore poses new questions about the social diversity of local memory cultures. This panel aims to examine the possibilities of integrating a range of objects in early modern memory research and to connect them in time and/or space. Participants are encouraged to consider a) which media reached which audiences b) how different media interacted with each other and their audiences c) which groups or individuals were important in the establishment of a memory landscape and d) which changes occurred within the landscape over time. Panel 4 Memory transmission and identity formation The relation between individual identities and the memory canons of groups and communities is a key question in the field of memory studies. In the case of early modern Europe, the way individuals were able to inscribe their own experiences and memories into the memory canons of groups and communities has not yet been studied extensively. While some theorists have suggested that in the early modern period the memory cultures of local and urban communities were the most important mnemonic framework for individual identities, studies on early modern religion suggest that confessional discourses about the past were also highly important. After all, these could bring together narratives of communities all over Europe, especially those of the great masses of migrants and confessional exiles. This panel aims at an evaluation of the question how local or confessional memory cultures could incorporate the experiences and identities of individuals and between which mnemonic frameworks individuals could choose or switch. In the case of migrants and religious refugees, the interrelations between affiliations to (new or old) local communities and the wider confessional discourses about exile could be an interesting case to study. Linking this question to theories about generational memory might deliver valuable insights into the processes of identification and group formation. As Aleida and Jan Assmann suggest, memories of historical events undergo a decisive transformation after approximately three generations when after the death of the last eyewitnesses ‘communicative memory’ is turned into ‘cultural memory’. Once this ‘cultural memory’ has provided a coherent discourse about the 3 past, it could be asked how the experiences of following generations relate to the conveyed narratives: which meanings were ascribed to the canonical past, how were they appropriated or contested and to which extent had traditions to be reinvented in order to make sense in the present? Papers in this panel may ask into which greater (communal, confessional, ‘national’) entities individuals projected their personal identities and how these various discourses competed with one another? How did personal and collective memories interrelate? Which were the media that could bring them together? How were memories transmitted and transformed over generations? Which role did public discourses about the past play in this process and to what extent did the transmission of memory influence the socialization of individuals in a group? Panel 5 Sensations of change Until a few decades ago, scholars who discussed the early modern ‘sense of the past’ limited themselves to texts which they recognized as ‘historical’, i.e. narrative accounts of the past or contemporary events, or on ‘theories’ of history. Since then, our scope has widened, first to include the activities of antiquarians and collectors, and lately also non-scholarly forms of engagement with the past. What used to be the ‘history of historiograpy’ has thus been transformed into the study of ‘historical culture’ and ‘memory’, and has also come to include the study of visual sources, material remains, performative acts etc. However, early modernists have as yet done little to examine what these findings might mean for the ‘grand narratives’ about the development of historical consciousness that were put out in the 1960s, and that continue to be extremely influential among theorists of modernity and modern memory. The objective of this panel is to revisit a key theme in these master narratives, that of the ‘sense of change’. Modern memory theory suggests that the French Revolution created a sense of rupture so irreversible, that it had a lasting effect on the historical consciousness and ‘sense of the past’ of Western culture. We invite contributors to this panel to consider: (a) to what extent earlier periods of great upheaval had created a ‘sense of change’, for instance among diarists, local chroniclers and memoirists; (b) whether such moments of rupture create lasting cultural transformations or a temporary sense of dislocation that wore off in a generation or two; and (c) what this implied for the extent to which novelty was integrated into, and appropriated by, the discourses about the old and right order. 4