ResourceCapability_model.V1.petercomments..doc

advertisement

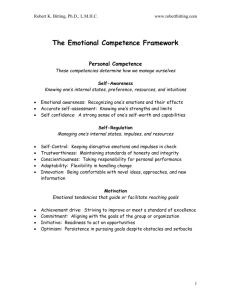

Knowledge Based (Resource & Capability) Ontology for Virtual Enterprises Brane KALPIC*, Peter BERNUS**, Krsto PANDŽA*** * ETI Jt. St. Comp., Obrezija 5, 1411 Izlake, Slovenia, brane.kalpic@eti.si ** Griffith University, School of CIT, Nathan, QLD, Australia, P.Bernus@bigpond.com *** University of Maribor, Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, Smetanova 17, 2000 Maribor, Slovenia, krsto.pandza@uni-mb.si Abstract: Enterprise capability to manage change became one of the key success factors in a highly dynamic and turbulent business environment. Networks and Virtual Enterprises represent one of the recent organisational concepts, which are attracting increasing attention of the research and business community. The concepts outlined in this article help organisations in managing change, improve their operational flexibility and give enterprises an opportunity to create a globally competitive and highly-complex operational competence through allowing network partners to focus on their core-competencies. The article proposes generalised and formalised definitions (and ontology) of key capability related notions . The developed model integratestwo complementary and highly related strategic management frameworks: the Resource-Based View and the Dynamic Capabilities Approach. The article also discusses the dynamic phenomenon of the development and reconfiguration of capabilities to emphasise the capability perspective of the organisational concept in question. Finally, the article proposes a Virtual Enterprise resource & capability ontology as a useful specialisation of the generalised resource & capability ontology by mapping the structural and behavioural characteristics and features of Networks and Virtual Enterprises. Keywords: resource, capability, competence, Resource Based View, Dynamic Capabilities, Network, Virtual Enterprise, ontology 1 1. Introduction In the contemporary business environment the unpredictability and dynamics of the environment is often experienced by enterprises as turbulance (Warnecke, 1993) – i.e. the enterprise is not prepared to handle the change using its usual business processes. Continuous change demands responsiveness and flexibility, efficiency and effectiveness in the organisation and in the execution of business processes. The result is that organisations are forced to: Restructure, and develop higher-level integration of business processes and adopt new organisational structures, Implement new management concepts and paradigms, Redesign traditional value chains and supplier – buyer relationships, Recombine and redesign the enterprise’s operational capabilities, etc. – and all this must be done by trying to reuse and redeploy existing organisational knowledge. Organisations handle the challenge of change in different ways. Winter (2003) identifies two major mechanisms for change: a) ad hoc problem solving or b) adopt or develop and apply high-level ‘patterned’ organisation routines (also called Dynamic Capabilities). Networks and Virtual Enterprises (VEs) are an example of a highly dynamic organisational structures, characterised by their flexibility and dynamic nature through constant development and restructuring of operational capabilities. These structures are characterised by their ability to set-up business opportunity driven capabilities on demand, where every particular order or business opportunity demands (triggers) restructuring or the development of a unique set and configuration of resources and capabilities respectively. The VE, as a goal-oriented and project-focused organisation, is a relatively new concept of cooperation among enterprises which takes advantage of a network organisation that is the ‘breeding environment’ (Matos-Afsarmanesh, 2000x?) of such VEs. The use of the VE paradigm facilitates the management of change and provides operational flexibility, because it is based on the combination and recombination of relatively stable organisational building blocks from multiple enterprises. The concept 2 offers network partners an opportunity to create a globally competitive and highly complex operational competencies while allowing each member of the network to focus on its core-competencies. In the literature, the concept of Networks and VEs (in terms of structural and behavioural characteristics and features), as well as resources and capabilities on a company level, have been well discussed and defined [reference]. However, the authors have experienced a lack of explicit and well-defined concepts and terminology concerning capabilities and resources when applied in a VE and Network environment. Since capabilities and resources are fundamental concepts in modern strategic management it is expected (or at least hoped for) that these concepts could help explain the dynamic nature of the organisational concept in question, e.g. to shed light on how to develop and reconfigure capabilities on the network and VE level. The question is non-trivial, because the authorities, ownership and management processes (including strategy making) are quite different on the network- and VE levels from those at the individual company level. In Section 2 the article proposes generalised definitions of the key notions, such as business processes, resources, capabilities and competencies, considering the basic tenets of the Resource-Based View (RBV) and of the Dynamic capabilities approach (DCA) [references]. Section 2 also discusses the nature of capability development and its reconfiguration,presents different possible pathways for the associated organisational change, and finally, it discusses the hierarchy of capabilities. Section 3 continues with a brief definition of the VE concept while Section 4 presents a mapping of structural and behavioural characteristics of VEs onto the generalised resource and capability ontology. 2. Resource and capability ontology 2.1 Business process definition The Oxford English Dictionary (1999) defines ‘process’ as a series of actions or operations conducted to an end, or as a set of gradual changes that lead toward a particular result. According to Davenport (1993) and the ISO9000:2000 family of standards (2000) a ‘business process’ is a structured and measured, managed and controlled set of interrelated and interacting activities that uses resources (as for instance different tangible and intangible assets, people and other external 3 resources) to transform inputs into specified outputs. Davenport also proposes a differentia specifica of business processes: every process relevant to the creation of an added value is a business process. Business process outputs can be categorised as (see the Figure 2.1): inputs to subsequent processes (the output of business processes BP1 is the input of business process BP3), resources for subsequent processes (the output of business processes BP2 is a resource necessary to carry out business process BP3 – e.g., the development of a new technology or specific assembly device is a resource for a manufacturing process), or final products delivered to the market (such as goods or services). Controls Enterprise BP1 BP3 Inputs Outputs (Products) BP2 Mechanisms (Human & technical agents) Figure 2.1: A simple model of a business process (consisting of business processes BP1, BP2 and BP3) 2.2 Resource definition A Resource is an entity, which is able to perform a certain class of operations involved in the transformation of input material and/or information into output(s). Resources are assigned to activities (or processes) according to their adequacy (capability and ability) to carry out operations or activities to deliver the required outputs. Strictly following the engineering consideration and terminology of resources (such as reflected in the IDEF0 modelling language (KBSI, 2001)), resources are the mechanisms that perform processes (see 4 Figure 2.1.). The Engineering definition of resource is in contrast with management and economics definitions (Investorwords.com, 2004), which latter include ‘transformation inputs’ (material, data & information, energy, cash, etc.) into the concept of resource. Accroding to the Engineering defnition ‘Resources are not consumed or transformed during activity/process execution’. According to the GERA modelling Framework of GERAM (2003) resources have two different forms of physical manifestation (and each of these can be human or non-human, i.e. automated): software (SW) is a (partially controlled) state of a hardware enabling it to perform certain operations (the knowledge of employees, a configuration of manufacturing facilities, a computer program, etc.). Thus software is an ‘abstract resource’ – it can only exist in hardware. ‘Software makes hardware to behave in a certain way’. hardware (HW) resources are physical entities that have the capability to perform some sets of tasks (in certain contexts and states). HW can be described by its capabilities (the set of operations / actvities it can perform under specified conditions). For a resource to be considered as a candidate for the performance of a process (or activity) it must meet the performance requirements of the process / activity. The division between HW and SW is related to (although it is not equivalent to!) the division of resources into tangible resources1 and intangible resources2. If we consider the company-specificity of resources, they can be divided into non-specific resources (or general purpose resources which could be acquired on the market, like machines, computers, software, etc.) and company-specific resources. Company specific resources (as well as capabilities), which fulfil the criteria of being valuable, rare, inimitable and non-substitutable (VRIN resources), can be considered as a source of potential competitive advantage of the organisation. Therefore the management of companyspecific resources is strategically important for any company. 1 Holdings of obvious market value real estate, or harder-to-measure value like inventory, aging equipment, etc. Other quantities considered an a resource by accounting conventions but possibly having no market value at all like goodwill (the value of a business to a purchaser over and above its net asset value; goodwill reflects the value of intangible assets like reputation, brand name, intellectual property, good customer relations, high employee morale, and other factors which improve the company’s business). Interesting – all this is related to knowledge, e.g. a set of beliefs is part of knowledge and goodwill beliefs that a set of customers share which makes them come to you not to your 2 5 3 4 The resources necessary to perform an activity/process may be owned and/or leased (note that company specific resources can not be leased or acquired on the market). 2.3 Capability Capability is a firm’s ability to execute relevant, interacting and interrelated business processes, linked with the common mission to transform inputs into specified (requested, expected) outputs by the use of resources. Capability represents a permanent or temporary integration, configuration and cluster of resources, defined by structural and behavioural characteristics of relevant business processes. Therefore, capability has an integrative property (function) and defines the behaviour of the organisation, this integrative property is a systemic property of the capability. The integrative property of the capability (its ‘mission’)may be: functional, the ability to perform a (sometimes complex) function, cross-functional, where capability can not be attached to a single particular function or a domain5 (several domains involved – e.g. heterogenity of resources incl knowledge) Capabilities may have qualifying properties; e.g. a capability which delivers superior quality goods or services, a design capability that can deliver innovative product designs, etc. Winter (2000) defines the organisation capability as a high level routine (or a collection of routines) where routine is considered as a behaviour that is learned, highly patterned, repetitious, or quasi-repetitious, founded in part on tacit knowledge (Nelson and Winter, 1982). Dosi et al. (2000) argue that a capability a) represents organisational – collectively held knowledge, which arises from integration and coordination of specialised knowledge and b) coordinates the performance of individual tasks. From the aforementioned knowledge-related definition capability appears to include form of meta-knowledge. competitor.[???] We need to discuss this part – what exactly fits in each of human sw/hw FIRO??? We may be able to discover something that is also related to the KM model!!! 3 Note that owned resources are a part of the organisation’s assets; assets are items on a balance sheet considered to have positive monetary value and showing the book value of property; beside resources, assets include inventory and cash. 4 Note that company specific resources can not be leased or acquired on the market. 5 A domain is a functional area achieving some goals of the enterprise (e.g., sales, purchasing, R&D, production, etc.); a domain is composed of stand-alone processes. 6 Winter (2003) also defines capabilities as complex, structured and, where capabilities build a hierarchy from ordinary, zero-level, operational capability to higher-order, dynamic capabilities. Capability as an entity has it own evolution, characterised by typical stages in the capability’s lifehistory. Helfat et al. (2003) identify four major stages: a) founding, b) development, c) maturity and d) possible branching into retirement, retrenchment, renewal, replication, redeployment and recombination. The capability hierarchy and capability evolution will be discussed in more detail in the Section 2.5. 2.3.1 Capability as a complex entity Capability is an entity, which can appear at different levels of complexity from low to high levels. Complex capability can be composed of elementary, lower level capabilities. Examples of elementary capabilities are: process- and technology design, design of IT process control, quality driven culture (such as shared processes of negotiation and co-ordination), etc. Different complexity levels and composition of capabilities from elementary, low level capabilities, make it difficult to explicitly differentiate between capability and resource. Namely, a low level capability can be perceived from higher–level perspectives as a resource that has the given capability. Capability, in terms of its structure and behaviour, is a complex entity, quite tacit in nature and consequently difficult to describe and formalise. Out of the aforementioned statement a simple rule can be written: “The more complex a capability is, the less it is formalisable”. Therefore, imitation6, replication7 or emulation8 of capability is difficult if not impossible and unfeasible; all these capability features make capability not tradable. I HAVE DOUBTS ABOUT THIS. DISCUSS IN PERSON? Perhaps the reason why complex capabilities are not treadable is that the combination of capabilities into a process that has a value-creating/adding function (i.e. capability) needs (a) integration of elementary functions into a more complex process [and the process may not be explicitely known by anyone in the company!] (b) an agreement contribute to this process ???? by organisational entities (individual or higher level aggregate) to If the process is known but only on th einformal level then it is hard to transfer it; if the individual capabilities are hard to leran then it is also hard to transfer it; if the process is known but only integrated through ad hoc means then the integration knwoeldge must also 6 7 Imitation occurs when firms discover and simply copy a firm’s organisational routines and procedures. Replication involves transferring or redeploying competences from one concrete economic setting to another. 7 be transferred (which knowledge, again may be explicitely known –formally or informally - or just tacitely] All this seems to call for a categorisation of capability building (perhaps through typical patterns of capability formation?). These typical formations may be identified by us using the following base: (a) Conversation theory [as an epistemological theory of knowledge transfer] (b ) our own knowledge model (c) our understanding of how preocesses may be composed + ??? anything else??? In certain cases a capability can be described. However this mapping (or description) of capability is associated by causal ambiguity9 (Lippman and Rumelt, 1982; Simonin, 1999) and imitation and replication of the capability in this case can be collapsed into a simple problem of information transfer. The problem is that models of the capability can not predict all behaviours that are relevant to decision making regrarding the capability or for the (re)learning of it. Thereore replication in practice is often impossible without transferring people (this could minimise investment in conversion of non-externalised knowledge into externalised one). For this reason, if a company is able to emulate the capability, the created capability will actually be company specific. 2.3.2 Capability role in resource productivity Studies of resource productivity have shown that two identical sets of machines, tools, etc. can have different productivities. Different productive value seems to derive and depend on how these resources are structured, linked and behave as a whole, or in other words productivity depends the specific structure of capability. Elements that constitute a capability do not exist in isolation from each other; they only have meaning and value when linked; out of subsequent discussion it can be concluded that the productivity of resources.is a property of the complex operational capability. Productivity, and therefore efficiencly, also depend on whether the processes involved in the capability are internalised (have become routine, tacit knowledge), or they are performed in an explicitely controlled manner. 8 Emulation occurs when firms discover alternative ways of achieving the same functionality. Causal ambiguity is a particular form of uncertainty and refers to the fact that the knowledge of the capability's underlying structure is always incomplete. 9 8 In practice we can find some examples where companies accumulate a large stock of valuable technical resources and still do not have many useful capabilities. 2.3.3 Capability value A capability’s value is hard to measure and quantify; the main reason for this seems to lie in the capability’s complexity, tacit nature and ‘environment’ (organisation) dependency (capability is company specific and endemic10). A capability’s value also changes over time when associated with the appearance of competition or possible substitutes. The appearance of competition (in terms of resource or capability substitutes, which are functionally similar to the original ones) or product substitutes can diminish the value of the capability. In a competitive environment, if a capability has no further extendibility, then the value of the capability can become obsolete (e.g. market has no longer a demand that can be satisfied using the capability in question). Capability has a positive monetary value (also defined as an opportunity cost) if it provides a competitive advantage for the company. As a conclusion: capability value differs over different time periods and in different business contexts; in addition it can be perceived differently form different perspectives. 2.4 Core competence Competence can be defined in its simple form as demonstrated capability. Core competence is a companyspecific demonstrated capability that distinguishes the company from its competitors and defines the essence of the company’s business. The firm specific (core) competencies? are? a source of the firm’s competitive advantage. Therefore, according to Hamel and Prahalad (1994) a core-competence must ‘pass’ a tests based on the following criteria: customer value – a core competence must make a disproportionate contribution to customerperceived value 9 competitor differentiation – the capability must be competitively unique extendibility – a core competence is not merely the ability to produce the current product configuration (however excellent that product line may be), but it also must be able to be used as a basis of potential new products. There also exists a tangible link between core-competencies and core-products; namely, core-products represent the physical embodiment of the application of one or more core competencies. Irrespective of how wide a company product portfolio can be, companies are, from the perspective of underlying core competencies, usually very focused and coherent. The Canon case study11 (Mintzberg at al, 1999) indicates that the portfolio of core competencies may be narrow - no matter what is the size of the company. Control over core-competencies or core-products respectively is essential for the company because it allows that company to shape the evolution and different applications of its competencies through embodying them in end-products. 2.5 Capability evolution - the Dynamic Capabilities approach In the contemporary business environment, organisations are faced with the high dynamism of unpredictable changes. Organisations have to be able to adapt to changes in internal and external business environments, which requires adaptivity, flexibility and organisational responsiveness. Capabilities may need to change, either because of external causes (imperatives of the business environment) or internal causes (snactioned by management decisions). Due to the dynamism of the business environment, organisations are faced with some key capability related questions (Barney, 1991; Nelson, 1991; Penrose, 1959; Peteraf, 1993; Teece at al., 1997, Wernerflet, 1984) : 10 what is the impact of external and internal changes on the company's capabilities and how should capabilities change as a result? how to sustain competitive advantage of the company in the changing business environment? which are ‘the environmental enablers’ of an organisation that allow capability development (or why certain enterprises are capable of developing new capabilities or renewing existing ones, while others are not)? In biology, endemic organisms are restricted or peculiar to a locality or region (to particular conditions in the environment). 11 Canon, for example, produces a wide and diversified portfolio of end products from binoculars to calculators, cameras, camcorders, copiers, document management systems, faxes, medical products, picture management, printers, scanners, security lenses, Visual Communication Systems, etc. At the first sight this seems to be an extremely wide portfolio of unrelated businesses. However, from the perspective of underlying core competencies, Canon relies on a much smaller set of core competencies in the area of optics, microprocessor control and imaging. 10 Organisations have different possible ways to change. Winter (2003) identifies two major change mechanisms. The first mechanism is ad hoc problem solving where actions appear as a response to novel challenges form the environment or other unpredictable events. This approach does not constitute a routine; therefore it is not highly patterned and repetitious but is at least ‘intendedly rational’. However, organisations may develop certain change management patterns consisting of rules, actions (or a behaviour) and structural principles (Eisenhard and Martin, 2000), where the pattern may be learned and contribute positively to the effectiveness of future actions or changes respectively. This pattern could be akin to a skill or routine and can grow into an organisational capability, called Dynamic Capability (DC). In other words Dynamic Capability is the capability to dynamically create or change existing capabilities. Teece at al. (1997) define DC as the firm’s ability to integrate, build and reconfigure internal and external competencies. The ‘mission’ of Dynamic Capabilities is not production of goods or provision of marketable services but rather building, integrating or reconfiguring the operational capabilities. Therefore, DC do not directly affect the outputs of the company, but indirectly contribute to the firm’s output through impact on operational capabilities. No matter how much companies would like to be rational and skilled in a change initiative, practice shows that the complexity of real life many times overtakes the scope of DC. Such real life situations require complementary combinations of ad hoc problem solving and DC. The successful maintenance of a skill or routine, relevant for a company change initiative or development of dynamic capabilities, typically requires frequent exercise. However, attempting too much change (perhaps in a deliberate effort to exercise the DC) can a) impose additional cost – because of frequent disruption of the underlying capabilities, and b) limit the ability to learn the lessons of any particular change (due to the bounded rationality of human beings). There is an ecological demand for a balance between the cost of the capability and the use that is actually made of it. (Teece et al) DC help us understand how idiosyncratic attributes of the individual firm affect its prospects in a particular competitive context. DC is also manifested in the company’s (management) ability of sensemaking (retrospective) and interpretation of previous events (decision impact on the current business reality) and imagination (interpretation of future needs and conditions); DC should make possible identification of 11 productive opportunities and creation of decisions about the development of new or reconfiguration and renewal of existing capabilities. The decision of where a firm can go, in terms of the future development of its capabilities or competencies respectively, doesn’t simply depend on some ‘rational’ process, which identifies different opportunities and considers industry attractiveness (for instance, decisions made on an analysis of Porter’s five competitive forces framework of industry attractiveness (Porter, 1980)). A firm’s trajectory of competence development is path dependent (Teece et al, 1997). Path dependency means that the choice about domains of competence is influenced by company (competence) current position, past choices and future possibilities and conditions. Namely, firms make long-term, quasiirreversible commitments to certain domains of competence, what could easily transform an organisation’s core capability into its organisation’s core-rigidities. On the other hand, paths ahead in the competence development should be influenced by understanding of the industry foresight (understanding of technological, life-style, demographics, economics, regulatory changes and trends which will affect the industry or competency). 2.5.1 Capability hierarchy From the discussion in Section 2.5 it derives that between DC and ordinary capabilities there exists certain hierarchy or rather recursiveness. Winter (2003) defines DC as high order capabilities that operate to extend, modify or create ordinary capabilities. DC govern the rate of change of ordinary capabilities. An example of DC represents the capability of new product development, which affects the product, production processes and the way in which customers are served. New product development capability represents a prototypical example of a first-order dynamic capability. The capability to create a new outlet (bringing together real estate, design skills, construction, equipment, advertising campaign, hiring and training of new employees, setting up processes, etc.), where the company has centralised staff focused on the creation of a new outlet, represents another typical example of DCs. In contrast with DC, ordinary, operational or ‘zero-level’ capabilities permit a firm to ‘make a living’ in the short term by producing and selling the product and collecting the revenue from its customers. 12 The relationship between DC and operational capability, in terms of the role of DC in the founding, development or renewal of operational capabilities, opens another important question – how and why companies are able to create DC. Similar to the aforementioned relationship, where DC create or reconfigure the operational capability, the analogy between company enablers (which make possible the creation of DC) and DC can be establish. The authors believe that the company should nurture certain high order capabilities, which make possible creation of DC. Among those elementary, high order capabilities belong: a) learning12 and knowledge management13 and b) management14 and leadership15 capabilities. 2.6 Capability as a knowledge category Knowledge can be described and classified based on different knowledge attributes and knowledge categories. Figure 2.2 presents some basic knowledge categories (Kalpic et al., 2004): tacit and explicit knowledge where o explicit knowledge is knowledge, which can be articulated and written down; therefore, such knowledge can be externalised and consequently shared and spread o tacit knowledge is developed and derives from the practical environment; it is highly pragmatic and specific to situations in which it has been developed; tacit knowledge is subconscious, it is understood and used but it is not identified in a reflective, or aware, way internalised and externalised knowledge where internalised knowledge is limited and present in a person’s head while externalised knowledge has a form of external records (as for instance written text, drawings, models, presentations, demonstrations, etc.) 12 Learning represents a capability by which repetition and experimentation enable tasks to be performed better and quicker. Learning of course involves organisational as well individual skills. 13 Knowledge Management (KM) incorporates different KM methodologies, concepts, tools, reference models, technologies (all classified as resources) and routines with the mission to formalise and spread organisational knowledge. KM includes different activities and processes as for instance: a) knowledge externalisation (form internalised to externalised knowledge), b) knowledge formalisation (from tacit to explicit) and structuring (from unformalised (unstructured) to formalised (structured) knowledge), and c) knowledge distribution and reuse. 14 Management in presented context represents ability for efficient and effective coordination of internal & external activities and resources. 15 Leadership capability (in presented context) represents ability of a strategic decision-making. 13 formal and not-formal knowledge where externalisation could have a formalised representation or not; formalisation here means that the external representation of the knowledge is in a consistent and complete mathematical/logical form (or equivalent) individual and collective knowledge where individual knowledge is limited to an individual and gives a person ability to carry out certain tasks; collective knowledge is shared by members of the group, where individuals contribute their personal knowledge into a cohesive and integrated whole (for instance the knowledge how to develop a new product); collective knowledge that the organisation posseses is more then the sum of knowledge of individuals in the organisation (or in other words, the productive value of the knowledge of an individual is higher when the knowledge of individuals is linked) conceptual and pragmatic knowledge where conceptual knowledge represents an abstract or generic knowledge generalized from particular instances; pragmatic knowledge is related to matters of fact or practical affairs (procedural or how to do knowledge). formal not-formal tacit internalised externalised individual collective explicit Knowledge pragmatic conceptual Figure 2.2: The knowledge categories Capability as a knowledge instance could be described by different knowledge attributes, which are related to the aforementioned definitions of knowledge categories. Based on the presented features of operational and dynamic capabilities it seems that operational capabilities fit most naturally with the category of pragmatic knowledge while dynamic capabilities could be related to the category of conceptual knowledge. Dynamic capabilities are manifested in an individual (top management) capability of sense-making, imagination and interpretation. DC are built on a) fundamental and conceptual knowledge of the relevant domains, b) pragmatic knowledge (usually applied in form of different frameworks, methodologies, tools, 14 etc.), and c) cultural and situation shared knowledge, which helps in the explanation and understanding of the past and present organisation behaviours and decisions as well as anticipating future needs and (productive) opportunities. In the presented context, DC represent the conceptual (abstract and generalised) knowledge about domain in question. Operational capability represents the knowledge of how to do things. This knowledge could be in some instances procedural, prescriptive and deterministic (for detailed definition of associated knowledge attributes see the figure 2.3) that give the knowledge feature an explicit knowledge, which could be potentially externalised and formalised. However, we should not neglect the fact that, many operational capabilities are highly complex and their associated business and decisional processes are unstructured or ad hoc in nature. This complexity makes capability difficult in its formalisation and imitation or replication what gives the capability property of tacit knowledge. Operational capabilities Tacit Explicit Dynamic capabilities X X Internalised X Externalised X Formal X Not-formal X Individual X Collective X Pragmatic X Conceptual X Figure 2.3: Knowledge attributes of conceptual and pragmatic knowledge 15 3. Enterprise Networks and Virtual Enterprises Contemporary enterprises co-operate with other enterprises in all phases of the product life-cycle to demonstrate a world-wide competitiveness and highly complex competence, which can speed up the product development process, increase their operational flexibility, achieve cost reduction and allow them to focus on core competencies (Tolle, 2003). This preferred method of cooperation between partners becomes a goal oriented, project focused co-operation usually done in virtual enterprises (VEs). While from the customer’s point of view VE is functionally identical to a company, the VE may be in fact a) a temporary association of companies to perform one-of-a-kind task (e.g. building a bridge) or b) an association of companies towards the purpose of performing some sustained task during a period of time. To present the relationship between network and VE, the example of network and VE life histories will be presented in brief. This example starts with the identification, preparation, and setting-up of the network. At some point in time, during the operational phase of the network, a customer contacts the network with a request for quotation. The Network delivers a quotation to the customer who later accepts the quotation. The network consequently sets up VE, which will deliver the quoted product (for instance product design and its building); therefore, the Enterprise Network can be considered as some kind of breeding ground for setting up VEs. When the customer’s requirements are satisfied, the experience gained in the VE are transferred back to the network; the VE is decommissioned and the network waits or seeks other possibilities on the market. Fast VE set-up could be jeopardised if the VE is composed of partners unknown to one another before the formation of the VE. As a part of forming an enterprise network, partners need to establish a degree of preparedness to be able to configure world-class competencies (in order to meet customer demands), based on the capabilities available in the network, in a short time. When setting up an enterprise network, one of the key questions to consider is the level and type of preparation in the network and among the network partners. Reference models (RMs) are important means in this preparation allowing quick, low-cost and secure VE creation. The purpose of the RMs is also to capitalise on previous knowledge by allowing model libraries to be developed and reused in a ‘plug-andplay’ manner rather than developing models from scratch. 16 4. The resource and capability ontology model for VEs and Enterprise Networks In this section the article separately maps and discusses the structural and behavioural characteristics and features of Networks and Virtual Enterprises through the perspective of resources and capabilities (see the Figure 4.1.). Network Partner Network Virtual Enterprise Product - VE with the mission to deliver - service to the VE (using - goods or services on (deliverable) the requested product to the the partner’s core demand (requested by the customer competence) customer) Core capabilities a) creation of a new capability - core competentce a) capability to deliver (competencies) (or VE) - capability on demand useful for some potential requested product b) Network management VEs according to VE b) capability to manage VE capability (to manage network requirements (known as a governance processes, resources, capability) knowledge, control of Network performance, decision making, etc.) c) Network partner development capability Resources a) knowledge about partner - Resources made a) committed by VE partners capabilities available / committed to (with their capabilities) to the b) Network Reference Models be used in VEs VE b) project (VE) management reference models c) VE specific models (as an instantiation of RMs) Dynamic- a) capability to learn - capability of network In case the VE is a long term Capabilities b) creation of a new capability partners – to learn and operation, it may have its own by establishing VEs improve functional and dynamic capability to re- alliance capabilities form organise (e.g. in case of participating in VE (which sustenained breakdown in the qualifies them to become opettion) qualified partners the network) Figure 4.1: The review of main resource and capability related features of Networks and Virtual Enterprises 17 4 .1. Enterprise Network The capability to create a new VE represents the core competence of the network, which has the particular mission to deliver the requested product to the customer. This creation capability is a high order capability and it has the property of Dynamic Capabilities; namely, the creation of VE is really about the creation of a new capability – capability on demand. The creation capability has an integrative property manifested in integration and structuring of network resources and partner capabilities into the powerful capability (VE competence), which compete on the market. The Network management capability represents another type of the network core capabilities with the mission to manage: network processes and resources, as for instance: marketing and sales, analyse customer requirements, setting up VEs, network partner qualification, etc. and network knowledge and associated knowledge processes: from capturing to formalisation of the knowledge (in the form of different reference models – RMs) or assessment of relevance and reusability of captured knowledge. Network management also includes some typical management tasks like control of task execution, measurement of the network performance over KPIs, decision-making, development (establishment) of the shared goal hierarchy among network partners (aligning of their mission, vision, strategies and objectives). To participate in the Network, the partner should posses functional and alliance capability (capability to integrate in the Network) and meet certain network requirements and standards. Consequently, the Network has to be capable of defining these requirements and standards for identification, selection, and qualification16 of network partners or their capabilities respectively. This identified core capability can be named Network partner development capability. Besides the operational capabilities of the Network some DC can be also identified. The Network capability to learn, in terms of experience collection and its mapping (as a part of VE decommission process) into a) new RMs models or b) modified existing RMs, represents a prototypical example of high-order (Dynamic) capability. Namely, with the learning process, the capability to create new capabilities (VEs) is improved and upgraded that also represents a typical path-dependency process. 16 In terms of installing any needed ICT systems, training of personnel, etc. 18 The Network operates on different resources, where some of them are ’firm’ (Network) specific as for instance knowledge about partner capabilities (what partners are capable of doing). This knowledge is a typical example of meta-knowledge. Network Reference Models represent another very important type of Network resources, which could be used in a ‘plug-and-play’ manner in the process of VE creation. There are many different examples of RMs, as for instance: business process models organisational and decisional models legal – contractual models IT infrastructure (for instance access rights and standard interfaces) environmental and quality management (in the form of procedures and manuals) network KM model standardisation, etc. 10.2. VE VE represents the deliverable of Network processes and activities. The VE mission (and core-competence) is delivering goods or services on demand requested by the customer. VE core competence is usually manifested in a functional type of the capability (focused on the performance of the particular function – e.g. design and delivering of the product). To be capable of delivering requested products, VE also has to demonstrate capability to manage VE in terms of: management of VE processes and resources planning and scheduling of VE activities and resources ensuring that the partners have a VE related and shared goal hierarchy – i.e. VE mission, strategy and objectives controlling of task execution and performance of VE or 19 decision-making related to VE operation. The presented capability can be also named as a governance capability. DC, in the case of VE, is recognised in the form of network partner capability to learn and improve their functional and alliance capabilities from participation in VE. The VE operates on VE internal and external resources (members of the VE) where three major categories of resources can be identified: a) VE partners (where partner capabilities are perceived from the network or VE perspective as resource, that represents the abstraction of the resource), b) project (VE) management reference models and c) VE specific models as an instantiation of Network RMs (for instance process models, organisational models, resource models, quality procedures and standards, etc.). 5. Conclusion The article discusses the ontology model for Networks and VEs. This ontology model is built on the premises and influential theoretical framework of RBV and DCA. The model defines company capabilities as an integration and structure of company specific17, company non-specific and external resources into a productive configuration. Capabilities of strategic importance which meet the criteria of a) contributing disproportional customer value, b) competitor differentiation, and c) extendibility of capability application (in terms of end products) could be considered as a core competences of the company. Capabilities (competences) compete on the market with competitors; the market is the only one which approves the competence competitive advantage, its productive opportunity and what is the competence true value. The presented model also introduces and discusses the role of DC in the highly dynamic phenomenon of capability creation. Dynamic Capabilities, as meta-capabilities, are those capabilities, which create and develop new or renew and reconfigure existing capabilities. DC represent routinised response to familiar types of organisational changes. 17 Company specific resources could be a deliverable of company capabilities (for instance specific, own developed technology, machines, computer software, etc. or a created well known brand name) or could be ‘environmentally’ conditioned like locational or institutional assets (public policies are recognised as important in constraining what firms can do). Locational assets for instance represent a specific company location in a certain geographic market, from which company gains low transportation costs, fast response on a market demands or improves other key success factors. 20 Considering a capability as knowledge instance and following the presented knowledge categorisation, this article identifies certain correlation between operational and dynamic capabilities with different knowledge categories. It seems that operational capabilities fit most naturally with the category of pragmatic knowledge while dynamic capabilities can be related to the category of conceptual knowledge and associated attributes. Finally, in the section 4, the article presents the mapping of structural and behavioural features of Networks and VEs in resource and capability ontology model and Network and VE capability, DC and resource instances in the presented model. References: Barney J.B. (1991) Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), pp 99 - 120 Davenport, T.H. (1993) Process innovation: reengineering work through information technology. Boston (MA): Harvard Business School Press Dosi, G., Nelson, R. R., Winter, S. G. (2000) The Nature and Dynamics of Organizational Capabilities. Oxford : Oxford University Press Eisenhardt K.M., Martin J.A. (2000) Dynamic capabilities: what are they?. Strategic Management Journal, Special Issue 21 (10-11), pp 1105 - 1121 Hamel, G., Prahalad, C.K. (1994) Competing for the future. Boston (MA) : Harvard Business School Press Helfat C.E., Peteraf, M.A. (2003) The Dynamic Resource-Based View: Capability Lifecycles. Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 24, pp 997 – 1010, www.interscience.wiley.com IFIP–IFAC Task Force on Architectures for Enterprise Integration (2003) GERAM: Generalised Enterprise Reference Architecture and Methodology. http://www.cit.gu.edu.au/~bernus/taskforce/geram/versions/geram1-6-3/v1.6.3.html Investorwords.com (2004) Resource, http://www.investorwords.com/4217/resource.html ISO/TC 176/SC2 (2000) ISO9004:2000 Quality management systems – guidelines for performance improvements Kalpic, B., Bernus, P., Muhlberger R. (2004) Business Process Modeling and Its Applications in the Business Environment. in Leondes, C.T. (Eds.) Intelligent Knowledge-Based Systems: Business and Technology in the New Millennium. Boston : Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp 288 - 345 Knowledge Based Systems, Inc. (2001a) IDEF Methods: IDEF0 Overview–Function Modelling Method. http://www.idef.com/idef0.html Lippman S.A., Rumelt, R.P. (1982) Uncertain imitability: an analysis of interfirm differences in efficiency under competition, Bell Journal of Economics, Vol.13, pp.363-80. Mintzberg, H, Quinn, J.B., Ghostal S. (1999) The strategy process – revised European edition. London : Prentice Hall Nelson R.R, Winter S.G. (1982) The Schumpeterian trade-off revisited. American Economic Review, Vol. 72, pp 114 – 132 Nelson R.R. (1991) Why do firms differ, and how does it matter? Strategic Management Journal, Winter Special Issue 12, pp 61 - 74 21 Oxford University Press (1999) The Oxford English dictionary. Version 2.0 Penrose E.T. (1959) The theory of the growth of the firm. New York: Wiley Peteraf M.A. (1993) The cornerstones of competitive advantage. Strategic Management Journal, 14(3), pp 179 - 191 Porter, M.E. (1980) Competitive Strategy. New York : Free Press Simonin B.L. (1999) Ambiguity and the process of knowledge transfer in strategic alliances. Strategic Management Journal 20(7), pp 595 - 623 Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., Shuen, A. (1997) Dynamic capabilities and strategic management, Strategic Management Journal. 18(7) pp509-33 Tølle M., Vesterager J. (2003) Developing the Business Model - A Methodology for Virtual Enterprises. in Bernus, P., Mertins, K. and Schmidt, G. (Eds.) Handbook on Enterprise Architecture Berlin : Springer-Verlag. pp 291-308 Warnecke, H.J. (1993) The Fractal Company. Berlin: Springer-Verlag Winter, S.G. (2003) Understanding Dynamic Capabilities. Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 24, pp 991 – 995, www.interscience.wiley.com